Treatment fidelity has been an important consideration in the research process of the LIVELY project, to ensure that the Research Assistants (RAs) carried out the interventions consistently, in line with the manual and in line with each other. Treatment fidelity has implications for the internal validity of the LIVELY project; however, it also bears on the future ability to apply the interventions to real clinical settings (Hinckley & Douglas, 2013).

We reflect on the challenges, processes and importance of standardising interventions to be used reliably by different researchers and ideally in the future by varying teaching staff, in differing locations, and with a range of children. Key are issues of developing approaches that can be individualised to support children’s specific needs.

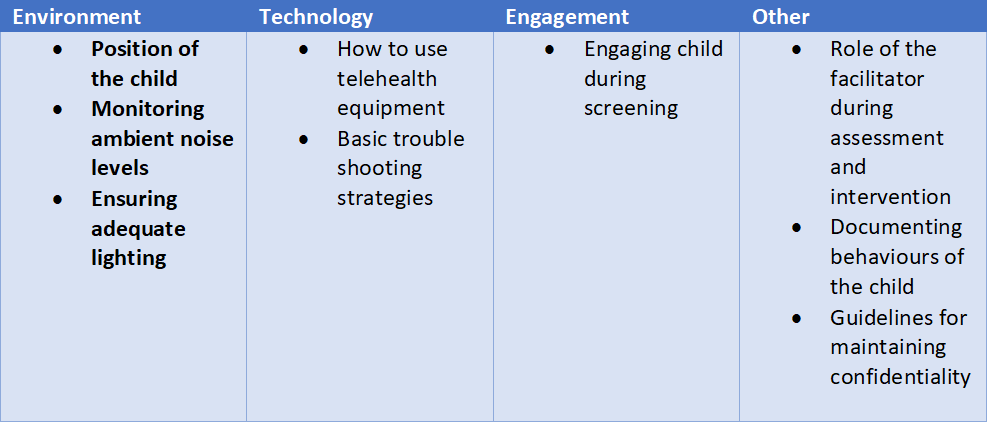

Key areas of consideration for high treatment fidelity are:

Manualisation of the Interventions

- BEST already had a manual prior to the project. The LIVELY RAs worked with Cristina McKean, Mark Masidlover and Christine Jack to create a manual for the adapted version of the DLS

- Clear assessment and intervention protocols were created to support the RAs to deliver the interventions consistently

Consistency of resources

- The team had to ensure that all toys and resources used in the interventions were exactly the same. Resources were adapted due to the pandemic – the toys selected were wipeable to ensure they could be cleaned after each use.

Development of treatment fidelity checklists

- A stand-alone treatment fidelity tool had previously been created for the BEST intervention. A treatment fidelity checklist was created to use with the DLS intervention to ensure it was being delivered consistently.

Methods of supporting parents to access and engage with homework

The involvement of parents in a child’s speech and language intervention has been highlighted as a significant factor of its success. Engagement of parents with homework resources can be tricky to control, however, methods of support to try and engage parents with activities were put in place:

- Simple and easy to use homework activities: lotto games, short stories, turn-taking and matching activities

- Video instructions for all homework activities

- Written instructions for all homework activities – including QR codes to access the video instructions

- Text messages sent to parents after each session with a link to the homework resources and video instructions

- Providing teachers with homework instructions so they can support any parent questions or queries

During the LIVELY project, treatment fidelity was monitored throughout the intervention period. RAs kept weekly reflections regarding any barriers and enablers, what worked well, what could be improved and how. The RAs could not see each other’s reflections during the project to ensure they remained blind to the treatment arm. Intervention sessions 3 and 4 were also video recorded, watched by the RA and then rated using the treatment fidelity checklist. The videos and self-reflections were then sent to a supervisor who also watched the videos and used the treatment fidelity tool to score the intervention session and provide feedback to the RA. The comprehensive manuals and protocols discussed earlier were put in place to try and mitigate any compromise to the treatment fidelity of the interventions.

For more information on treatment fidelity in the LIVELY project, please see the presentation attached which was presented at the virtual Research Symposium.

Staying%20Faithful_RS%20presentation.pptx – Google Drive

Authors: Emily Preston, Jo Baker, Kate Conn

References

The following list includes references from the presentation and articles that may be of further interest to you:

Bellg, A. J., Borrelli, B., Resnick, B., Hecht, J., Minicucci, D. S., Ory, M., . . . Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the, N.I.H.B.C.C. (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychol, 23(5), 443-451. Doi: 10.1037/02786133.23.5.443. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15367063

Bruinsma, G., Wijnen, F., & Gerrits, E. (2020). Focused Stimulation Intervention in 4- and 5-Year-Old Children With Developmental Language Disorder: Exploring Implementation in Clinical Practice. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch, 51(2), 247-269. doi:10.1044/2020_LSHSS-19-00069

Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., & Balain, S. (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci, 2, 40. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-2-40

Fricke et al, (2017). The efficacy of early language intervention in mainstream school settings: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(10), 1141-1151. DOI: 10.1111/jcpp.12737

Gearing, R. E., El-Bassel, N., Ghesquiere, A., Baldwin, S., Gillies, J., & Ngeow, E. (2011). Major ingredients of fidelity: a review and scientific guide to improving quality of intervention research implementation. Clin Psychol Rev, 31(1), 79-88. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.007: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21130938

Glogowska, M., & Campbell, R. (2000). Investigating parental views of involvement in pre-school speech and language therapy. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 35(3), 391-405. doi: 10.1080/136828200410645

Hinckley, J. J., & Douglas, N. F. (2013). Treatment fidelity: its importance and reported frequency in aphasia treatment studies. Am J Speech Lang Pathol, 22(2), S279-284. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2012/12-0092): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15367063

Klatte,I. S., Harding, S., & Roulstone, S. (2019). Speech and language therapists’ views on parents’ engagement in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT). International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 54(4), 553-564. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12459.

McKean, C., Benson, K., Jack, C., Letts, C. A., Pert, S., Preston, E., Trebacz, A., Stringer, H., & Wareham, H. (2020). ISRCTN10974028: Language Intervention in the Early Years – comparing the effectiveness of language intervention approaches for pre-school children with language difficulties ISRCTN doi: 10.1186/ISRCTN10974028

Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., … & Wood, C. E. (2013). The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : a Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

Ory MG, Jordan PJ, Bazarre T. The Behavior Change Consortium: setting the stage for a new century of health behavior-change research. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(5). doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.500

Roulstone, S. (2015). Exploring the relationship between client perspectives, clinical expertise and research evidence. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(3), 211-221. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2015.1016112.