A sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis) stranded on the beach in the early morning yesterday in Druridge Bay. It was first reported as a minke whale but at closer inspection it was found that the 8.6m whale was a young female sei whale. This is only the sixth specimen ever stranded in the UK, so a very unique event. The whale was alive when it stranded and was reported to the British Divers Marine Life Rescue (www.bdmlr.org.uk) that has trained staff to deal with live marine mammals. BDMLR makes every effort to refloat stranded animals that are in good physical condition. Unfortunately, the sei whale was emaciated and the local veterinary that was called out to assess the health status of the animal made the final decision that it was too weak to refloat. The vet therefore euthanized the animal which this case was considered the humane approach to end the animal’s suffering. Even if the whale had been healthy enough for refloating this would not have been an easy task. An 8.6m sei whale weighs about 5-6 tons and that takes a lot of lifting power to assist the animal back into deep enough water.

Once a marine mammal is dead it becomes the responsibility of the Defra funded UK Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme, to carry out a post mortem to investigate what may have caused the animal to strand (http://www.facebook.com/pages/Cetacean-Strandings-Investigation-Programme-UK-strandings/142706582438320). A CSIP team from the Institute of Zoology (IoZ), Zoological Society of London (Rob Deaville and Matt Perkins) came up from London up to Morpeth. IoZ contacted Dr Per Berggren, our school’s marine mammal expert, for assistance. Per together with Simon Laing (Newcastle University) and Dan Gordon (the Great North Museum) arrived at the stranded whale at 5pm just in time for the post mortem.

Once a marine mammal is dead it becomes the responsibility of the Defra funded UK Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme, to carry out a post mortem to investigate what may have caused the animal to strand (http://www.facebook.com/pages/Cetacean-Strandings-Investigation-Programme-UK-strandings/142706582438320). A CSIP team from the Institute of Zoology (IoZ), Zoological Society of London (Rob Deaville and Matt Perkins) came up from London up to Morpeth. IoZ contacted Dr Per Berggren, our school’s marine mammal expert, for assistance. Per together with Simon Laing (Newcastle University) and Dan Gordon (the Great North Museum) arrived at the stranded whale at 5pm just in time for the post mortem.

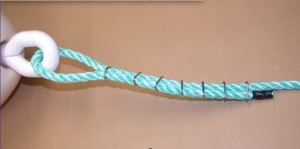

The post-mortem starts by taking a series pictures and measurements of length and girth of the animal. This is followed by stripping the skin and blubber off one side with the help of the car winch! The relatively thin blubber thickness and muscle condition confirmed the emaciated state of the animal. Samples were then taken from various tissues including skin, blubber, muscle, lung, liver kidney, brain, ovaries and uterus. A gross examination of parasites showed non-elevated levels (all marine mammals have some parasite load in e.g. lungs, kidneys, liver, stomach and intestines). There were a couple of pieces of plastic found in one of the animal’s three stomach but neither this nor the parasite load were likely to have caused the animal to strand.

We collected a range of samples that will be used for genetic, foraging ecology (using stable isotopes) and contaminant analysis which will be conducted in collaboration between IoZ and Newcastle University. We also kept one of the flippers, the dorsal fin and some baleen which eventually will be displayed at the Great North Museum.

We would have liked to save the entire skeleton but would then have needed to bury the carcass for up to a year to get the bones cleaned by the bugs in the ground. Unfortunately, this was not allowed in this case due to the extremely potent sedative that was used to euthanize the animal which made it necessary for the carcass to be taken for incineration.

So what caused the animal to strand? Sei whales are not native to the North Sea so basically this juvenile female was in the wrong place at the wrong time. She clearly had not been eating properly and this gradually made her weaker and made her start metabolising blubber and muscle tissue. The confusion of being in an unfamiliar area and the severe weather conditions during the last few days likely made her lose her bearings and strength and caused her to strand. A very sad ending for such a magnificent animal.

Description of the sei whale

The sei whale has a mainly offshore distribution in the North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Hemisphere. They migrate between winter mating grounds in tropical and subtropical latitudes to summer feeding grounds in temperate and sub-polar latitudes. They can be found off the northwest British Isles in the summer and very rarely in the North Sea.

Adult sei whales reach a length of 12–17m and weight of 20–40 tonnes (females slightly larger than males). Primary prey is small crustaceans like copepods and euphausiids (krill/shrimp). Sei whales reach sexual maturity when they are around 14m in length, at 8–9 years. Females give birth to one calf every two years. The lifespan of the sei whale is estimated to be 53–60 years. Sei whales have 300–400 baleen plates in two rows (left and right), suspended from the upper jaw. The body of the sleek sei whale is coloured dark grey above and light grey-whitish on the throat, belly and the underside of the flippers and tail flukes.

Sei whale populations were subject to commercial whaling in the North Atlantic until the 1970s. Surveys reveal little sign of recovery of sei whales in the northeastern Atlantic. A survey in part of their summer range revealed around 10,500 animals in 1989 since when there have been no catches. There are currently insufficient data to undertake an assessment of their status (www.iwc.office.org). Sei whales are currently listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/2475/0). Sei whales are still a target for modern whaling and Japan takes 100 animals per year in the North Pacific as part of their scientific permit catch.

The name ‘sei’ is Norwegian for the saithe fish (Pollachius virens) and was given to the whale because both the fish and the whale occur in Norwegian waters at the same time each year. The sei is the third-largest whale after the blue and fin whales.

Per Berggren