There’s a thing that’s been doing the rounds on Twitter over the past few weeks, termed variously ‘#7days7books’, or ‘#7daybookcoverchallenge’ or ‘#7daybookcover’. The idea is that you Tweet images of book covers over 7 consecutive days, and challenge someone else to do the same when you do so. You are instructed not to include any explanation or justification – just the images of book covers. I’ve been spending more time than I should looking at what gets posted under this hashtag, because I’m interested in book covers. This is mostly an outcome of the military memoirs work that Neil Jenkings and I have been doing over the last ten years; we ended up thinking a lot about their covers and their role in book marketing. When we interviewed military memoirists we asked them to explain to us why their books looked like they did. They had some really fascinating observations on this, and you can read our discussions of this in the chapter ‘Why Do Military memoirs Look Like They Do?’ in Bringing War to Book. If you can’t get hold of a copy of the book and want to read the chapter, get in touch with me direct (rachel.woodward@newcastle.ac.uk).

I was tagged in the book covers challenge by a colleague, and of course couldn’t resist. I decided that all the covers had to be of military memoirs. But selecting just seven was tough; I’ve got 250+ military memoirs on the shelves in my office, and those are just the ones about participation in the UK armed forces and published after 1980. And then I found it impossible to randomly tweet images of the selected seven without wanting also to say something about why I was so drawn to these covers. So I felt a blog post was called for.

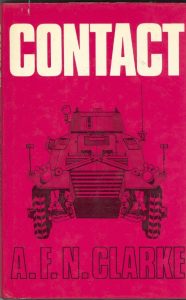

- F.N. Clarke, Contact, (Secker and Warburg, 1983)

I like the dark pink, and I like the line drawing; no other military memoirs in my collection use either this colour or this style of illustration. I think the vehicle shown is an FV603 Saracen (I had to do a bit of web-browsing to work this out – apologies if I have this wrong), an armoured personnel carrier in use by the British Army in the 1970s. The singular title and a line drawing give nothing away. This is one of the Northern Ireland deployment memoirs. There are not that many of these in existence (Neil Jenkings and I have written about this here). A.F.N. Clarke’s account draws on his two tours of Northern Ireland with 3 PARA, to Belfast in 1973 and to Crossmaglen in 1976. I’ve found it a useful and illuminating book for a number of reasons. I’ve just flicked through it again, and have found inside a note-to-self from a number of years ago saying ‘John Hockey says this was made into a BBC film’. John is always a well-informed source, so I need to check this out. I did another quick web search, and I see that Contact was re-issued in 2010 in a revised edition which includes text about injury and trauma suffered by the author that had been removed from the manuscript prior to publication of the first edition. So there’s a story there that I’ll have to look into too. I’ve ordered a copy of the revised edition. It has one of Jonathan Olley’s Castles of Ulster photographs on the cover – a stark military landscape.

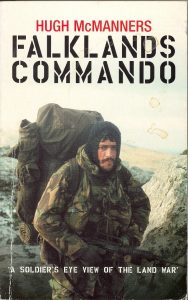

- Hugh McManners, Falklands Commando (originally published by William Kimber & Co, 1984, cover below from HarperCollins edition, 2002)

I bought this book in 2003, when I’d been doing some work on the idea on rurality and military masculinities, and was starting to get interested in military personnel’s accounts of the spaces and places of their deployment. I remember picking the book up in the shop, looking at the cover, and deciding to buy it on that basis. The picture above is a scan of my copy, which has been read a number of times as you can see by the creases and the coffee stain on the cover. The image credits in the book indicate that the photograph was taken during a specific operation (Brewer’s Arms) during the Falklands War. Author images make for good book covers because they communicate the idea of veracity (so important to military memoirs given the number of people who will take issue with the idea of their ‘truth’). This image is striking; the author’s face is lit by the sun, and his rifle is visible but in shadow. He looks cold and tired and battle-worn. He fixes us with his stare, and we can guess at fatigue by looking at the size of the Bergen on his back. The distinctive stencil font clarifies this as ‘military’, as if we hadn’t already guessed – a cliché, I know, but effective nonetheless.

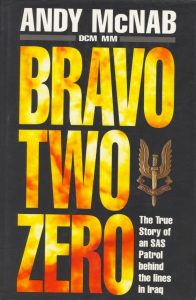

- Andy McNab, Bravo Two Zero (Corgi, 1994)

I bought this when I first started doing research on military-related things (mostly the politics of military land use) in about 1997, and I realised that I knew virtually nothing about the organisation and structures of the British Army. I had tried to read a few things like Charles Heyman’s pocket books, but as useful as these are, they aren’t exactly light reading. I saw Bravo Two Zero on sale and realised I recognised the title, but knew little else about it. So I bought it. Once I started reading, I couldn’t put it down. The book is about a Special Forces operation in Iraq during the 1991 Gulf War; the operation is compromised and the story unfolds around what happens to McNab and his colleagues in the aftermath. It’s an action-adventure memoir that’s still worth reading; the fact that it sold about 1.5 million copies is indicative. As for the cover, there are several significant features: the use of fire, indicating destruction, chaos and rebirth; the use of McNab’s post-nominals to signal his credibility and achievements as a soldier; the use of the SAS winged dagger, ever-present on the covers Special Forces books to indicate its potential appeal to a particular market segment (read John Newsinger’s Dangerous Men for a full account). Bravo Two Zero, famously, has its detractors, and there are a number of interesting stories about the afterlives of this book and its cultural effects. I’ve got a more recent edition of Bravo Two Zero with an updated cover using more contemporary military memoir design features (armed men in silhouette, visible rifles, a helicopter, use of muted sandy colours). These are common in memoirs from the 2000s, from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, and the re-designed cover was produced presumably to introduce the book to a new readership. But I have a fondness for the original – the use of fire and the winged dagger are repeated on the covers of many Special Forces memoirs, but this one’s The Daddy.

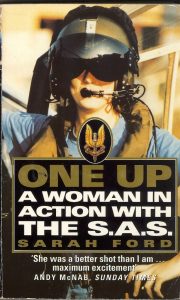

- Sarah Ford, One Up (HarperCollins, 1997)

Military memoirs written by women are fairly rare – at the last count I had ten by women in my collection of 250+. This is because of the smaller number of women having a military experience to write about (even in 2019, only 10.4% of the UK’s armed forces are women), and because of publishers’ primary interests in specific types of narratives relating to direct combat roles, roles from which women were excluded until very recently. The military memoirs written by women have tended to be about women in exceptional roles – although across this small collection, they accord in the main with the conventions of the genre as a whole (Claire Duncanson, Neil Jenkings and I have written a chapter about gender and military memoirs here). I like this cover because it shows, simply, a woman dressed for her job. There’s nothing sexualized about the image either (unlike the covers of some other memoirs by women). The book itself is well worth reading; it’s Ford’s account of her military life which included attachment to Special Forces in Northern Ireland, and it’s one I’ve used a lot when trying to think about both gender issues in the military, and things like the movement of personnel through spaces of deployment (she is deployed because, being a woman, she has access to spaces and access to modes of intelligence gathering not available to men). And the implications of familiarity in the endorsement is also interesting (McNab is a serial endorser of military memoirs, and there’s something to be written about that too, another time).

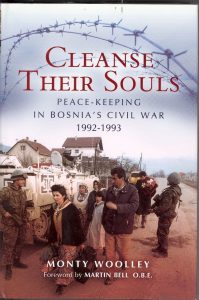

- Monty Woolley, Cleanse their Souls (Pen & Sword, 2004)

This is a memoir of peacekeeping in Bosnia; the author was a Lieutenant with the Cheshire Regiment battlegroup deployed in 1992-93, and the story centres around his witnessing of atrocities. The image show what looks like a displaced family; there is rubble in the background and the sense that it is a cold winter day. The abjection of the family is notable, and the hand of the man front and centre in the image is blurred, as if he’s gesturing to someone off camera. There’s no photo credit (that I can find, anyway) in the book, and I’ve wondered a number of times whether this is one taken by the author, or whether the author is one of the two soldiers shown. It is a striking image because military memoirs rarely have covers showing civilians caught up in war. Catherine Baker has written a number of interesting papers on the experiences of British military personnel in Bosnia, and her work explores issues of language, translation and communication, and the difficulties and politics of this in the British deployments to Bosnia. This book captures something of those issues, I think.

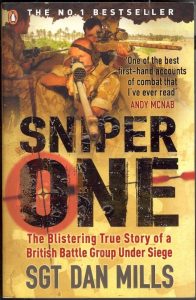

- Dan Mills, Sniper One (Penguin, 2008)

This is such a great example of contemporary military memoir cover design that I had to include it. It has everything: the stencil effect typeface for the title (and when you hold the book in your hand you appreciated that the title is slightly embossed on the card of the cover); the cross hairs around the letter O; the use of sandy-camouflage design in the background; the palm trees to indicate a vague sense of location; the inclusion of a very visible weapon (which I assume to be a sniper rifle); and images of three figures which look like they could have been superimposed on each other from three different original sources. We see another Andy McNab endorsement, the idea that this is a popular book selling in high volumes, and the sub-heading indicates very clearly what kind of account this is likely to be. I’ve seen a more recent edition with ‘The book they tried to ban’ included on the cover, and this will always help with sales (though I’m not sure, and must check up on, the reasons for this). This cover was really helpful to Neil and I when we wrote a piece on military masculinities and public narratives of war, available here.

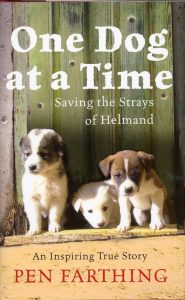

- Pen Farthing, One Dog at a Time (Ebury, 2009)

I like showing an image of this cover when I give lectures or talks about military memoirs. I put the image up on screen, look out at the audience, and watch as they go ‘awwwww’ and start to smile. Puppies. What’s not to like? It’s also a really interesting example to think about when trying to determine the parameters of the military memoirs genre. Neil and I have always worked within the definition of a book as a military memoir if it is written as a first-person, non-fiction account of deployment by a military operative in some kind of military context (which needn’t necessarily include armed conflict). So according to this definition, we include it as a military memoir, because it is about the activities of the author and colleagues on a tour in Afghanistan in 2009. But the author and publisher categorise it within the genre of true-life animal stories, and booksellers position it there on the shelves of their shops, rather than in the military history section where military memoirs are usually found. The author’s comment when we interviewed him was that it was a kind of ‘Marley and Me – with guns’. Because although it’s a deployment story, the narrative focuses on the activities of Farthing and colleagues in rescuing stray dogs. When the author returned to the UK, he set up the Nowzad charity which works for animal welfare in Afghanistan – activities like vet training, animal neutering, anti-rabies programmes and the like. What seems to me to be significant about this book – and the cover is crucial in this – is that it works as a mechanism for telling people who wouldn’t necessarily have kept up with news media reporting, about the activities of British forces in Helmand in Afghanistan. Many people who wouldn’t have access to information about the experience of those deployments would learn something about them through reading about dog rescue. I won’t go into the politics of representations of the Afghanistan war (Neil and I have written about that here), and I don’t want to suggest that the dominant narrative should be one of dog rescue. But in talking about dog rescue, the author managed to reach a readership that other military memoirs wouldn’t, and that has to be a useful thing.

Rachel Woodward