(Updated July 2024)

This is a shortened and slightly sweetened version of an article I will soon submit to Social and Cultural Geography and it’s the first major (and belated) output from my AHRC Living Legacies funded project at the McCord Centre for Landscape in 2017-18 called “War and the Moral Outdoors”.

If I could describe the project in one sentence, here’s what War and the Moral Outdoors would sound like.

When people have to face up to war, and their role in the horrors of war, some of them look for better, brighter moral alternatives to those horrors in the landscapes – rural and urban – that they visit.

Unfortunately, it’s quite difficult to describe War and the Moral Outdoors in one sentence, so instead I have split it into four ingredients. Here they are.

The first ingredient is Ruth Dodds. Ruth was born in 1890 to an affluent and relatively significant Gateshead family and from her early teens she was an avid diarist. She and her family were politically active and left leaning, which Ruth expressed by joining the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies and, later in life, the Labour party. She was nominated as a parliamentary candidate for Gateshead twice between the First and Second world Wars, but she was never elected. She was 24 when the First World War started, and she was 25 when she began working (part time) on the artillery shell production line at Armstrong Whitworth’s in Elswick. In that same year, 1915, she and her sister Hope published one of the key historical works on the major uprisings against the dissolution of the monasteries. Ruth, along with her sisters, was also a co-founder of the Little Theatre in Gateshead. Ruth, and all the wonderful contrasts that make her, is the first ingredient.

The second ingredient is Ruth’s diary (or more correctly, diaries, because there are many). Ruth’s diary is a constellation of poems, short stories, fantasies, deep ontological discussions with herself, and imaginaries of the future. It’s like a portfolio of her creative work and critical thought – at least in draft form, with some “ordinary” day-to-day diary content thrown in. She continued to keep her diaries over the war years and those diaries are now cared for at Tyne and Wear Archives. Ruth’s diary, specifically the many entries from the First World War, is the second ingredient.

The third ingredient is Ruth’s landscapes. Landscape is the principal character in Ruth’s diaries and it effervesces from the pages. It effervesces beautifully, and sensually, and – more than anything – urgently, because when Ruth strode outdoors she did so with an urgent need to harvest the moral qualities of landscapes. Her daily life in what is still a leafy suburb of Gateshead was never less than comfortable, but she still had to endure a horrifying world that seemed happy to abide industrialised slaughter. Given that she was a munitions factory worker her contribution to that slaughter was also clearly apparent to her. Ruth coped with that world and its horror – in which she was implicated – by seeking out better forms of living that coursed through and animated the (generally rural, generally upland) landscapes that she loved: better ways of existing and co-existing, better examples of stability and permanence, better examples of beauty, and better examples of justice. This moral outdoors is the third ingredient.

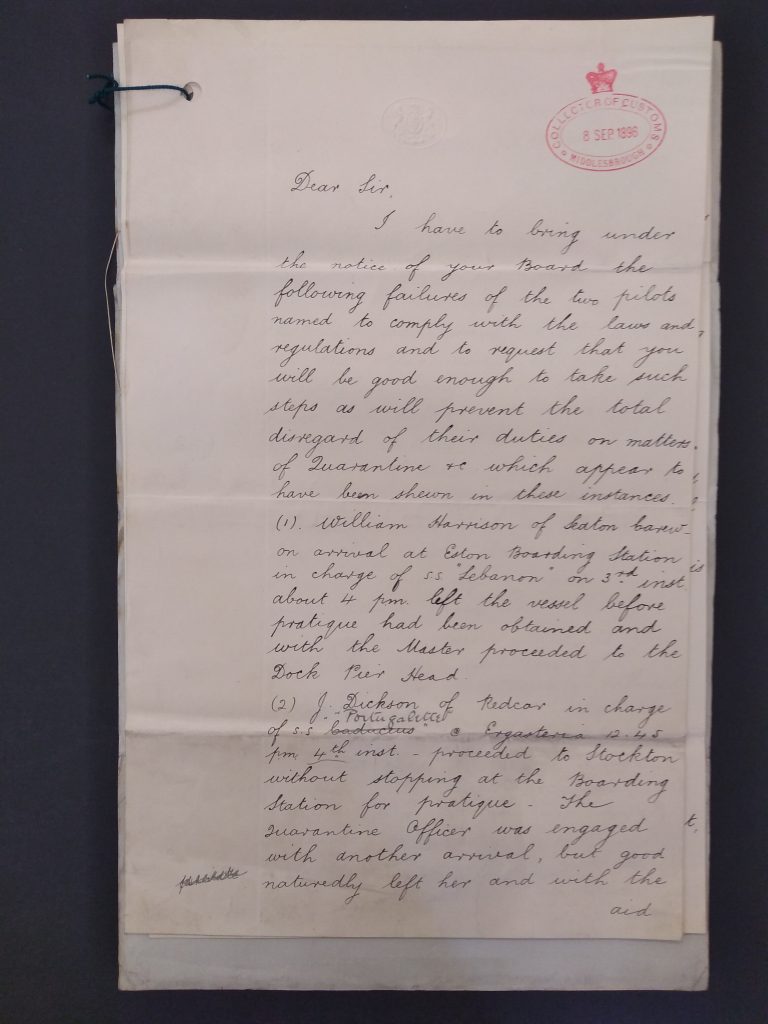

The fourth ingredient is the particular present-day encountering of Ruth, her diary, and her landscapes. I recruited and trained volunteer researchers to analyse Ruth’s diaries, who would draw out the coping moments where outdoor places gained moral form, and work towards reproducing these narratives as local walking routes. Each project researcher received pages from Ruth’s diaries via printed diary packs: each pack contained between sixty and ninety digitally photographed pages from a given diary, enlarged to approximately twice their original size, contrast-enhanced in greyscale for readability and with note-taking space to the side where the researchers could record their emphases, their interpretations, datums and locations. Some locations were suggestions because Ruth sometimes discussed landscape as features, tones and sensations rather than named locations, and here the researchers could (and did) suggest suitable locations. This encountering is the fourth ingredient, and it’s the one I’m going to discuss now.

To be specific, I’m going to discuss the two rich seams of insight that the diary pack encounters produced… the diary packs allowed the researchers to find all kinds of different ways that Ruth framed her need for a moral outdoors during the war years, and all the different ways she tried to make the landscape haul her difficult moral burdens. That’s my first seam.

Each diary pack also recorded the different understandings that the researchers developed when they were presented with Ruth’s diaries, and asked to understand her geography of coping. Because, remember, the purpose of having and analysing the diary packs was to understand Ruth enough to create walking routes that annotated her urgent need for a moral outdoors (those routes are, regrettably, still in the pipeline three years later). The diary packs were designed to capture what the researchers did to try and embroider Ruth’s stories back into the landscapes she loved. That’s my second seam and, to be clear, the researchers were fully aware of it.

For this short and sweet version of War and the Moral Outdoors I want to focus on just three key moments from the diary packs, the first was the passage which gave me the idea for the project back in 2016, the second was researched by Heather, and the third was researched by Nancy – please note that these are not their real names. All three moments emphasises the kind of material that Heather and Nancy responded to: in the following quote from 1915 you’ll hear Ruth as she segues between verse, personal reflection, and everyday life. This passage, written near the time Ruth stated work on the artillery shell production line, refers to Aidos, the Greek goddess of humility, and Nemesis, who can be understood either as the goddess of retribution against the arrogant or, I think more commonly, as the goddess of justice and the fair distribution of fortune (I freely admit that this is not my area of expertise, so I am simplifying Aidos and Nemesis this to “humility and justice”).

May 20th 1915. A dedication. To Aidos and Nemesis this altar amidst the green boughs of the orchard is set up, and to them are daily offered fresh flowers. Not here, O heavenly ones, not within these sheltering walls may you linger. But as you pass to and fro amidst the hatred and strife of men, shed on their hearts the peace of the garden and the gentleness of the flowers.

To me, it is a cheering thing that the world goes on the same in spite of us, and indeed if we could we should never be such fools as to forbid the leaves to come and the thrushes to sing because we were unhappy. That wouldn’t mend matters. The “heartless aloofness of nature” is all stuff. It seems to me a splendid sign that there are good and beautiful things beyond our control, that we who inhabit the world are only a small and feeble part of it, that with all our rage and hate and envy we can’t really spoil it.

I meant to begin this book on my birthday but the news of the Lusitania came and I hadn’t the heart.

This three-facet approach, of verse, personal reflection, and (often dire) contextual happenings is relatively typical of Ruth’s diaries: you can hear that they are far more than a recounting of events – as I suggested near the start of this podcast her diaries read more like a handwritten laboratory where she drafts and develops her creative work and crafts her critical thinking. When I first saw this in 2016, whilst working on a preceding project, I was immediately struck by the possibility that Ruth applied her intent and imagination to landscapes to make them expressly moral (and I continued to find regular, striking examples throughout her diaries – enough to support a project). This is all well and good for me, but how would Heather and Nancy approach this kind of content?

Nancy was not alone among the project researchers in noting sometimes excitable, often lyrical, but always deeply detailed manner that Ruth wrote of her outdoors experiences. Some of those experiences are presented in verse or as stories but even when they’re presented in ordinary prose the phrases seem to bump and tumble eagerly against one another as if they can’t quite be written quickly enough. Nancy found the detail striking in her diary pack where she notes, asking: “Does she write in such closely-observed detail of her life in Tyneside? Does she write in such a way that she feels her Tyneside life is her natural place to be? I doubt it”. Here is a short example of the kind of material Nancy was referring to, a 1918 day trip to Alnmouth… and now here’s Ruth.

June 2nd. Went to Alnmouth and bathed, it was perfect. Such a blue, blue sea faraway and the sands golden and the rock pools clear as crystal and a clear clear lucient green sea where the breakers are: oh the flash of light along the thin trembling green crest of the wave just before it breaks in foam, snowy foam. Coquet Island in the rainbow haze and oh, the links’ yellow for buttercups and vivid vivid blue (that’s speedwell) and greeny-yellow again for ladies’ bedstraw and all on a green green ground and the smell of it! A tall handsome purple thing with long juicy leaves grew by our luncheon spot…

Here and elsewhere the meaningfulness of Ruth’s diaries rests on detail, and the researchers’ didn’t care much for allegory or metaphor in that detail (even though Ruth’s text could be richly endowed with both). Neither Heather or Nancy claimed that a given word or phrase had been crafted by Ruth to reveal, when “unwrapped” by an astute reader, a hidden trove of meanings and connotations. But both Heather and (in this case) Nancy found that the detail Ruth committed to had affectual meaning: not significance in the details, but the significance of Ruth being detailed per se and to have set that detail down in her diary. So Nancy didn’t analyse that detail to look for a singular feelings (such as freedom, or peace), she analysed it as a potential: for Nancy, detail gives this landscape the potential of being emotionally significant. As more and more detail emerges on the pages of her diary, more and more potentials for different emotions are layered onto each other. That potential doesn’t have to become particular – it doesn’t have to be invested in one or more emotions we might give a name to. Put another way, Nancy’s analysis seems to suggest that Ruth’s approach to landscape is not particularly emotional but vastly emotional, and that Ruth engages with landscapes to make the most of the emotional possibilities it offers for her, gathering them and retaining them in their vastness.

And this is interesting, because I had expected at the outset of War and the Moral Outdoors for the volunteer researchers to seek out specific emotional spates and events. But Nancy wasn’t interested in limiting Ruth’s potential this way, and as we switch to Heather’s approach we can see this affectual stance in another format.

Heather’s retelling of Ruth was different to Nancy’s because her moral outdoors was a performing methodology: she wanted to perform Ruth, to get as close as possible to Ruth, to take a walk as though she was Ruth, and to look at things as Ruth did. Other project researchers wanted to interpret Ruth differently

There are two useful closing points that I’d like to make which, I hope, will give some idea of the critical direction I’d like to take insights such as those I gained from Heather and Nancy. I come from a background of heritage geography where, as with human geography and the humanities more generally, there is a continuing and increasingly complex engagement with affect. Affect is part theory, part ethics, and it celebrates the notion of incessant becoming. I have a nice example I use to understand affect and what it means… imagine a person approaching a piano. They are both things, a human thing and a non-human thing, and a traditional non-affect analysis says that their coming together allows for certain possibilities to emerge. The emphasis is on “certain” here, because our non-affect analysis suggests that a few things could happen in this encounter, and some of those things are relatively likely. So, with can be cautiously certain that the top three happenings are: 1) that the person could be indifferent, or 2) sit at the piano and press some keys, or indeed 3) produce a recognisable tune. Here there is comfort in cognition – the human thing will encounter the piano thing cognitively, construe the possibilities that fall to hand, and select one.

An affect-minded analysis of the same claims that the coming together of the person and the piano allows for uncertain possibilities to emerge in profusion – the piano could be booby trapped, the person could sit on it, it could roll away, the person could throw cutlery at it – each thing in the encounter incessantly multiplies the possibilities they bring, no one thing predominates. That analysis further states that things are in a constant state of encounter: things are constantly bumping against one another and multiplying their possibilities as they do – they are constantly becoming, a quivering and frenetic state of potential described by the philosopher Henri Bergson and which underlies much, perhaps all thinking on affect. That incessance means that whilst the expected may mostly happen (i.e, our top three piano moments), there is such a profusion and incessance of happenings that soon the encounter must rupture into newness and unknowns. Here cognition is not credited with bringing the encounter to heel – the non-cognitive is equally as powerful

This paper is not supposed to have a methodological focus or to dwell on my research choices, but the diary packs raise an overall methodological point worth emphasising: I fashioned the diary packs as the principal research encounter of this project – they combined the primary material and the project workspace. By reprinting enlarged, high contrast pages from Ruth’s diaries I changed her diaries, digitally shifting them away from their physical smallness, occasional illegibility, and papery fragility in the hope of creating a less challenging research space for the researchers to produce better analyses. The note-taking space next to the enhanced images was significant and, in hindsight, troubling for the same reason: it both invited and expected a “big” response to Ruth’s words… something more than a quick foray with a highlighter. Using a highlighter would suggest spotting interesting things, but the note-taking space demanded that researchers go a stage beyond spotting/highlighting by composing a response to the diaries. As the principal research encounter of the project, the diary packs were heavily laden with my hopes and concerns and, moreover, my designs on the researchers’ behaviour. This, perhaps, is another layer of data that the diary packs captured.