It’s nice to share new work, and today I’m sharing – below – an expanded abstract of a paper I’ve recently submitted in open call to the 2021 RGS-IBG conference, which has the theme Borders and Bordering and which speaks to my ongoing work on Perpetrating Landscapes.

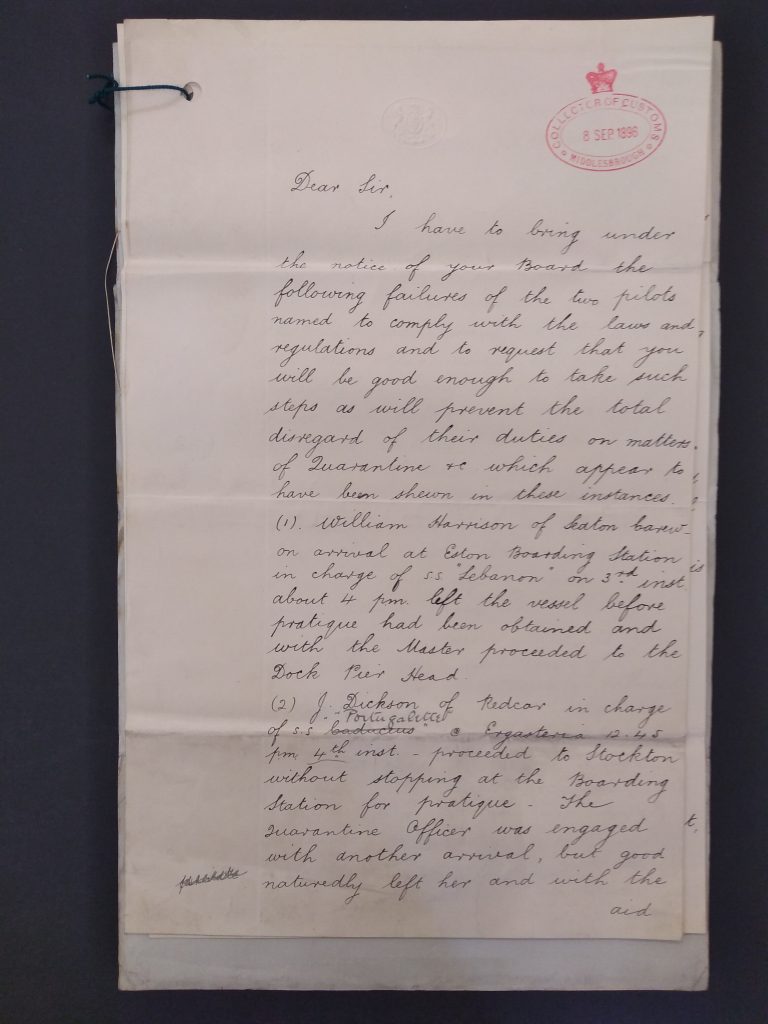

I’m quite excited by this paper… It emerged from a brilliant project I worked on led by the also-brilliant Fiona Fyfe in 2019: our client was the SeaScapes partnership, and the ask was to produce a comprehensive Historical and Archaeological Review of the Durham Heritage Coast. As part of that project I uncovered a small nugget of archival treasure that started the idea – this holding is from Teesside Archives, dated 8th September 1896, and it’s the start of a fascinating story about a performed border at the mouth of the River Tees…

Here’s my abstract – at the moment it’s a conference paper, but in the near future (and hopefully with another trip to Teesside Archives) I’m hoping to submit this as a journal article.

This paper concerns how borders are inscribed as features upon seascapes, or perhaps more accurately, how borders are inscribed as features upon the littoral, those coastal areas where the sea and land are incessantly giving way to one another. One way of making borders in the littoral is “pratique”, which is a collection of bordering intentions and practices used to decide whether a ship requires quarantine because it is suspected of carrying disease, or whether it is safe to enter a port (“free pratique”). Currently used to refer to human health, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century pratique was used – slightly incorrectly – as a general term concerned with any potential means of disease coming ashore.

(Aside: for those of you familiar with seascapes and borders, this might raise an eyebrow… as far as I know pratique is only supposed to apply to people – to determine if a ship needs quarantine because the people aboard are carrying communicable diseases. But the holdings I’ve seen at Teesside seem to suggest that both mariners and customs officials used the term “pratique” to cover disease, pests and pathogens that might be found among the crew, passengers, or cargo (the latter we are increasingly familiar with as post-Brexit “phytosanitary checks”). I do not know if this conflation was the norm elsewhere, although I’d be interested to. Anyway – back to my abstract:)

Intentions and practices matter here – the particular border that pratique creates is a coming together and holding together of instructions, understandings, and cultural imperatives: pratique performs a littoral border into existence as a land/seascape feature through key people and institutions delivering their roles (this includes customs officers, pilots, ships’ masters, loadmasters, radio operators, and others). The substance of this paper is that this land/seascape feature, crafted as it was from such performances, could be perpetrated against and upended by the wrong kind of performances.

(Aside: I’ve submitted this abstract now, but if I could go back I think I’d adjust my phrasing in the last sentence… I think “diverging performances” or “alternative performances” or perhaps “creatively wrong” performances, or even simply putting “wrong” in inverted commas would have had more fidelity to the idea I’m trying to express… this is a case of the impact of the phrasing eclipsing what should have been a more critical use of language. One usefully slapped wrist for me.)

Records from Teesside Archives show that in 1896, off the mouth of the River Tees in North-East England, pilots who met and boarded ships bound for port were adjusting their performance of the littoral border, convincing the crews of those ships that pratique was unnecessary (or else simply omitting to mention it). I want to analyse these records as a moment of land/seascape “perpetration” where a land/seascape feature can be seen becoming dysfunctional and leaky. In this analysis I don’t think of this border being any less a feature because it is performed, but I suggest that in being performed there were latent possibilities for perpetration that pilots seized on. Aiming to re-establish this littoral border, other performers in this land/seascape asserted that the border performed care and strength: it was a caring act for the fragile biologies of the land, and it could only be located at the littoral which had the unique strength to apprehend the harm. In short, bringing the notions (and character traits) of care, fragility, and strength into the narrative was a performance tactic to revitalise the perceived need for a border, and to return it as a feature.

This paper is an examination of this border, and how it shifted according to the performances that might make it a feature.

(Final aside: how does this connect to Perpetrating Landscapes as a wider project? Well, first of all, not too neatly – which is fine, even healthy, because Perpetrating Landscapes is a new project and (at the time of writing) a project where the concepts are still brewing. But the bigger story here is that the land/seascape at Teesmouth was formed and pulled between these different and sometimes shifting performances. It’s very easy to assume that a border feature is a kind of perpetration, i.e. a draconian offence to a landscape that seems so flowing (no pun intended) and fluid (slightly intended) in antithesis to bordering. But even though this border was performed with a certain amount of officiousness and (perhaps) squeamishness, it was formed out of care, and worry, and when the Tees pilots made a perpetrating landscape out of it (by performing holes into it), officials counter-performed by invoking care/fragility/strength. Their correspondence began to strongly emphasise that the “pratique border” at Teesmouth kept children from sickening and crops from wilting, and extended a caring hand over the places and peoples inland of Teesmouth and the Durham coast. It is an interesting move that I’m hoping to write more about.)