Rashida Campbell-Allen (@rashidacallen) is a 3rd year undergraduate combined honours student at Newcastle University. In this, the first in a two-week series of blogs from undergraduate students at Newcastle about Black Lives Matter and systemic racism, she reflects on social media and ‘performative’ activism.

The death of George Floyd is not a wake-up call. In fact, the same alarm has been echoing since 1619, but ignorance and privilege have hit the snooze button time and time again.

News of Floyd’s death spread like wildfire across the globe and as it did, I was overwhelmed with emotions, being a black woman myself. Anger, trauma, confusion and frustration. But also, a sense of excitement for the changes the uproar could provoke.

In a contemporary digital era, it is unsurprising that social media has become the arena within which most of our lives and interactions take place, especially in the midst of a national lockdown. Whilst social media can act as a useful source of information and a platform for communication, it also enables anonymity, detachment and performativity.

Anti-racism is neither a trend nor transient, because racism has been historically omnipresent and persistent. However, there is something about this particular occasion that feels different. Is it that everyone has more time to be on social media now, meaning more time to engage and pay attention to such incidents? Or was it that for the first time in my lifetime, white people were publicly waking up to self-reflect on their whiteness and listening not just to hear, but to understand, respect and raise black voices?

Spaces such as Instagram have become saturated with #blacklivesmatter content, from images, resources and petitions as well as brand and celebrity statements. While this exposure is welcomed, I cannot help but be sceptical of the effectiveness and longevity of these actions.

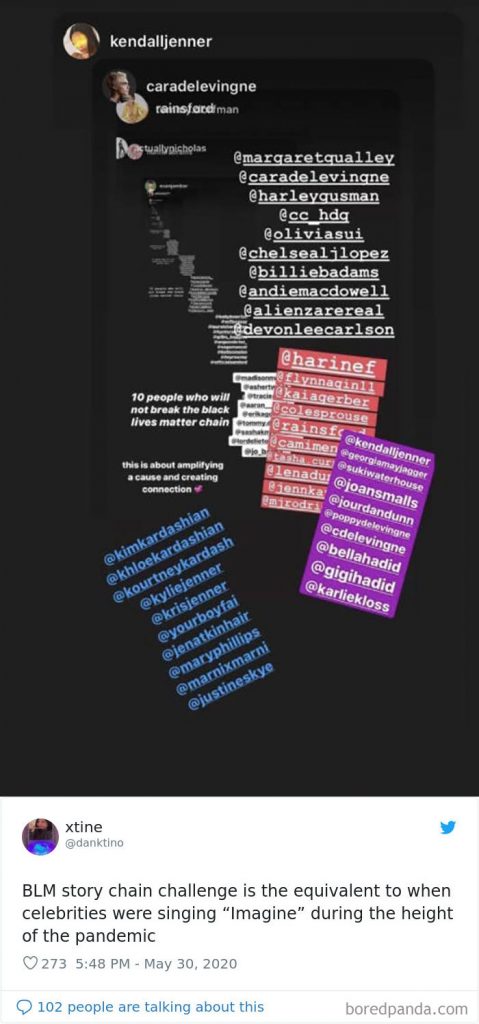

For example, there were numerous ‘chains’ being shared, where accounts were tagged, calling people to continue the chain and proclaim that they are not racist.

This self-indulgent proclamation and performative solidarity felt trivial and insulting, because who were these posts really helping? It seemed an easy way for white people to feel safe and assured that they are one of the ‘good’ ones. This showed how social media poses a risk to anti-racist efforts by encouraging performative behaviour instead of taking real action and interactional change. Having my timeline swamped with these posts spoke to the very way white people can use their privilege to selectively and comfortably (dis)engage with conversations about race.

Another example which really unsettled me was #blackouttuesday. Waking up on Tuesday 2 June, my heart felt heavy. Why did it appear like the world had closed its eyes and taken a break from the movement? As if white people were being granted some breathing time to digest everything. I then learned that it was rooted in activism and change. A way for the music industry to take a commercial break to avoid distraction and centre the focus on BLM. However, on Instagram, that intention was quickly warped.

Social media turned the black box into a superficial trend. My timeline was plastered with black squares, uploaded by people who had said nothing supportive in the days prior, and as if their activism existed within the four walls of this empty black space. To this I say no. Being non-racist does not make one anti-racist. It requires real recognition and mobilisation of privilege. Signing petitions, reading up on Black British history, provoking conversations amongst white friends and family members. Using your privilege to donate money if possible and so on.

Whilst I am filled with pride and optimism that social media activism has provoked real change, as seen in recent passing of progressive laws in the US and reopening of cases in the UK, I am reluctant to see what the future landscape of anti-racism will look like. Will this be another phase of activism that will eventually sink back into the shadows? When another piece of news replaces the headlines, will the anti-racist work continue offline?

Institutional statements and engagements with these trends also demonstrated how social media can create opportunities for hypocrisy. Newcastle Student Union posted a black square with advice on how to be an ally and support the movement. However, the university received backlash and calls to do more than join the trend, because of a previous lack of transparency and action to racism within the institution, in addition to the memorials of Martin Luther King Jr and Frederick Douglas being called “tokenistic gestures”. In response, the university emailed a much-awaited and welcome response to students which began to acknowledge the need to go beyond tokenism thus highlighting the impact black students and anti-racist allies can have. Hopefully, we will continue to be heard in the future so that this moment is not fleeting.

I want people to understand that true allyship and anti-racism is not a trend. Allyship and anti-racism is not a week-long performative act. Being anti-racist is a realisation that race is a universal matter – not just an issue for black people. It is lifelong commitment to self-reflection, action, education, awareness and listening to constructive criticism. Your black squares and hashtags are not enough. Your shock is not enough. In this case, actions need to speak louder than words.

Is chain-mail on social media really indicative of “white people [using] their privilege to … disengage”? All chains on social media come with a measure of emotional blackmail related to a significant issue. (“I want to see how many people will ignore my mental-health message”; “I love my daughter! if you love your daughter too, pass this message on”). Someone has to decide that not passing it on doesn’t mean they’re disrespectful of whatever issue it says on the jar. When “silence is violence” who wants to be the one who says “but a chain message is no message at all?”