Freddie Hall is a 3rd year Politics and Sociology student at Newcastle University. In the third blog of our Black Lives Matter series, he argues that our approach to tackling racism should mirror that of the ongoing effort to control COVID-19.

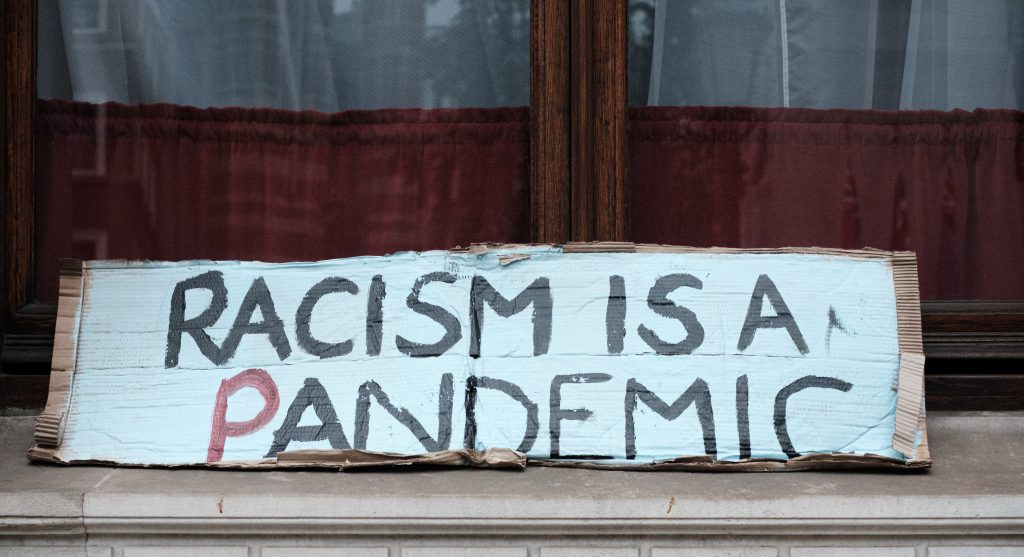

“There is a virus greater than COVID-19 and it’s called racism”. These were the words painted across one placard as protestors in the UK took to the streets, following the tragic killing of George Floyd. Professor Gary Younge, writing in the New Statesman, also highlights how it is systemic racism that has been the real killer of black people during the pandemic, citing inequalities in housing and employment as examples of such injustices. “Being black is a pre-existing condition”, he writes. These arguments, that Britain is in the midst of social crisis as well as a health crisis, do raise questions. If racism is a virus then shouldn’t we start treating it as such? More specifically, what can our anti-COVID-19 strategy bring to the fight against racism?

Key to the strategy to defeating COVID-19 is knowledge. Research allows us to understand the character of the virus – where it came from, how it is transmitted, what its symptoms are – and by establishing what it is we are up against, the government is able to take more informed action in order to tackle it. From the beginning of the pandemic, research from the scientific and medical community has been extensive, rigorous and has stopped at no lengths to uncover critical information about the virus. It is with this state of mind that we should approach the fight against racism in UK. We need to relentlessly ask ourselves uncomfortable questions about racism – where it comes from, how is it spread and at what levels it currently exists. Afua Hirsch, writing in the Guardian, argues that many “British people are ignorant about how racism works”, and there have been calls in recent weeks to address this ‘ignorance’ through the education system. One such call has come from Lavinya Stennett, founder of ‘The Black Curriculum’ campaign, who has questioned how racism is taught in schools. She argues that too often the “teaching of racism individualises it” and that more attention should be paid to how it operates on a structural level (Cranshaw, 2020). This is particularly prescient in a UK context, where racism exists in a less overt capacity but permeates all spheres of life.

A successful anti-COVID-19 strategy also relies on testing. Testing is seen as the crucial way of identifying the scale of the virus and thus enables us to gain the bigger picture. Also significant is how the numbers related to testing are presented by the government. They are updated every 24 hours and placed visibly in the public sphere, routinely read out in the daily Downing Street press conferences. The numbers have been hammered into us, ingrained in our memories. Could we recall how many black people were stopped and searched by the police last year? Through the establishment of the UK government’s ‘Ethnicity Facts and Figures’ website, there has been some effort to centralise figures on racial disparities. It was concerning, however, to discover that on the issue of overcrowded housing, the latest statistics to be published on the website were from the year 2016/17. This matters even more in the context of the current health crisis, with inequalities in housing widely seen as a significant part of why the black community has been disproportionately affected by COVID-19. There are arguments that numbers are relatively unimportant when it comes to the fight against racism and that it is action that makes the real difference. This view is misplaced. Numbers focus minds. They quantify the threat we face and inject urgency to address it. The words of the World Heath Organisation feel fitting: “test, test, test”.

If testing is about gaining the bigger picture, then tracing is about getting a more refined view. Through tracing, the government is able to locate virus hotspots. This targeted approach can bring many benefits to fighting racism in UK. Evidence suggests that racism is particularly prevalent in certain areas of society, as revealed by inquiries like the McGregor-Smith Review. It found dramatic racial disparities in the workplace, such as in decision making structures, where just “6 % of the top management positions” are held by BME workers. Clearly this is an area that needs to be addressed and again, here we can see where the tracing system provides a useful template to adopt. Effective tracing relies on fast action in order to quickly bear down on virus hotspots. This decisiveness has been sorely missing when it comes to tackling racism. The British Medical Association this week criticised the government for removing recommendations from its report on the impact of coronavirus on BAME communities. Saying ‘lessons will be learnt’ is simply not enough. Defeating COVID-19 requires dramatic government intervention. The fight against racism should be no different.