Lucy Butcher (@lucyebutcher1) is a Newcastle Politics and Sociology graduate who, in the fifth blog of our Black Lives Matter series, takes on the idea of ‘reverse racism’.

Photo credit: Jack Raistrick Photography

In the UK, protests against George Floyd’s murder and a resurgence of support for the Black Lives Matter movement have sparked waves of education about the country’s historical and systemic racism. The public are learning of the UK’s repressive colonial past through, for example, the tearing down of a slave trader’s statue, which, in London, has led Mayor Sadiq Khan to set up a Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm and for local authorities across the country to review statues that arguably idolise slavery, colonialism, and racism in the UK. Recent petitions following George Floyd’s murder have highlighted the deep-rooted and inherently unequal systems in the UK including the ethnicity pay gap; the latter has since been debated in parliament. The protests have also pressured Boris Johnson into establishing a cross-governmental commission on ‘all aspects of inequality’ in the UK. Whilst each of these political motions are at risk of being only gestures, and not markers of systematic change, it is nevertheless worth acknowledging how the power of protest has put these agendas to the forefront. Racism is at least being discussed.

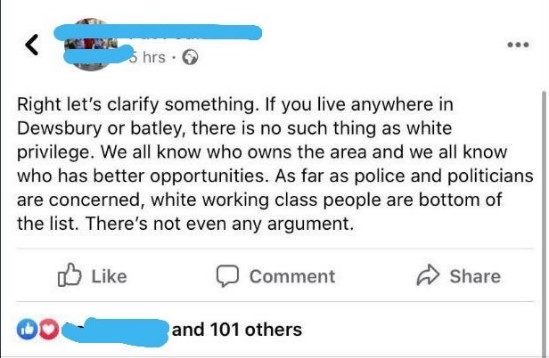

Yet, these recent Black Lives Matter protests have also been met with resentment across the country. Viewing this backlash on social media platforms within my local Northern working-class community of Dewsbury, West Yorkshire, I have witnessed attempts to undermine the anti-racist movement by misunderstanding the concept of ‘white privilege’, through arguments that poorer white people have had a difficult life, are subject to ‘reverse racism’ or consider themselves to be a minority due to the ethnic makeup of the area.

Dewsbury, my hometown, has a population with more South Asian people than the UK’s average. This fact is used to justify far-right racist beliefs such as segregation and the belief that majority Asian areas such as Saville Town are ‘no-go’ zones, which have led to hate crimes.

Building on these existing prejudices, I have seen a flurry of comments from family and friends decrying that “All Lives Matter”, arguing that by focusing on Black lives, the movement is attacking white people and disregarding their hardships. This demonstrates a lack of understanding of the systemic racism that instigated the Black Lives Matter movement, which tries to bring attention to the way that Black people are constantly being treated like their lives matter less than their white counterparts’. The Black Lives Matter movement has never been about saying that some lives don’t matter, rather, that all lives can only matter when Black lives matter.

For example, these views disregard how the anti-racist movement is one that seeks class solidarities; the working class is not only white. The three words ‘white working class’ mean that working class ethnic minorities are excluded from the possibility of forming class solidarities. White people can still be discriminated against based on social class, age, gender, or sexual orientation, but having white skin means that we have more advantages in everyday life. People of colour are also more likely to be working class than not in the North of England, and have been part of working class communities since post-world war. To state that as a working-class individual you face more discrimination than people of colour is to state that you do not even consider them to be capable of being working class, a rhetoric that distracts politicians from finding solutions to help working class people of all races.

Further to this, the idea of ‘reverse racism’ simply does not make sense because there is no systemic privilege afforded to ethnic minorities. For instance, people of colour in England are disproportionately more likely to die from COVID-19, have worse housing conditions, find it more difficult to gain senior positions in workplaces including education, are more likely to be stopped and searched for drugs, are more likely to live in poverty, are underrepresented in literature or fashion, and even find it harder to get a good haircut.

Some may argue that this doesn’t apply to working class areas within Northern England that have levels of poverty and deprivation (e.g. see above Facebook post). Yet in Northern England, deep racial and ethnic inequalities have been highlighted in the labour market, education, home ownership and employment. Even within West Yorkshire, within the last month, we have seen multiple reports of racism such as an assault by two white teenagers on a young black teenager in Holmfirth, racial abuse of an employee at a popular donut shop in Leeds, allegations of lack of due action and support for two young black girls who were racially abused at a Leeds school, and figures that show that West Yorkshire Police use force against black people three times more than white people.

Contrary to the suggestion that it is segregation that creates racial tension in Dewsbury, it is actually the rhetoric and criticism of anti-racism by white residents. It has justified extreme right-wing beliefs as seen in the regular far-right demos held in the area by the Yorkshire Patriots, Britain First and the English Defence League. This normalisation of racist ideas in the local area can have dangerous effects on the community. It contributed to the murder of local MP Jo Cox by Thomas Mair, whose neighbours believed that he “wouldn’t hurt a fly”.

If the people of Dewsbury, and the whole of the UK, really think that All Lives Matter they should stop spouting discriminatory ideas like ‘reverse racism’ and criticism of anti-racism protests, and try to listen to the experiences of their black and brown neighbours.

Reverse racism does exist in the UK. Just go into the Halifax Building Society. There are several large posters of black and brown people but not one of a white person. Why.