Claire Gardiner (@claireg98) is a fourth year Sociology and Philosophy student at Newcastle University. In the final blog of our Black Lives Matter series, Claire writes about how important it is to de-centre one’s own ‘whiteness’ in order to become truly anti-racist.

We white people have grown used to most spaces being tailored to our needs and feelings. The positive portrayal of white people in the media, the spotlighting of the white perspective in colonial history and the disproportionately high representation of white people in many schools and workplaces are just a few of the multiple ways this happens. By default, social structures focus on white people’s comfort and, as a result, we are not required to confront how we benefit from people of colour’s discomfort. Thus, it is not surprising that even during the large-scale ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement we have seen a centring of white voices and sentiments.

Obvious examples of this are seen in white people’s self-victimisation when we are called out for racism. For example, at the beginning of June, Ivanka Trump was supposed to give a commencement speech for Wichita State University Tech. Given the timing of the Black Lives Matter protests and the Trump administration’s militant and controversial response, the university decided that it would be insensitive to present Ivanka as a role model.

Ivanka responded on Twitter, claiming to be a target of “cancel culture and viewpoint discrimination”. She implied that the university was censoring which viewpoints were presented to its students and, subsequently, claimed it was an illiberal attack on her freedom of speech. By centring herself as the victim, she created a form of equivalence, while diminishing her privilege and diverting attention away from why her speech was cancelled in the first place. Post-racial narratives and narratives of racial equivalence are mobilised to assert that white people are now the victims of structural oppression, in order to re-centre whiteness and deny racism.

White privilege also manifests in performative displays of anti-racism online. Performative allyship is when someone in a position of privilege shows support for a marginalised group, but for superficial purposes. Whether it is to feel good or prove that you are a ‘good’ ally, these motives centre on whiteness and the feelings of already privileged groups (see Rashida Campbell-Allen’s blog in this series). Performative acts tend to be unhelpful, and can be actively harmful, because they draw attention away from marginalised groups.

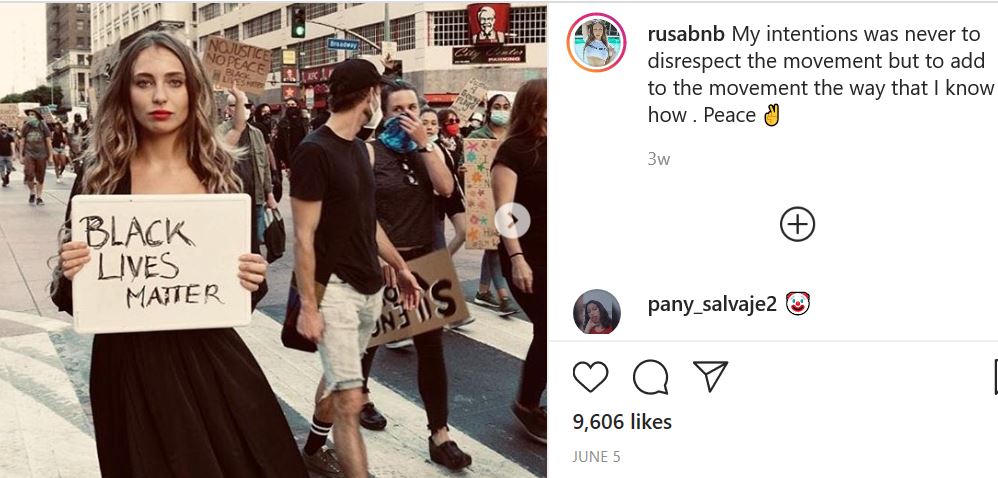

For example, (white) social media influencer Kris Schatzel was spotted having a photoshoot at a Black Lives Matter protest for Instagram (above). Of course, we do not know what anti-racism work people do behind the camera, and in an age of social media, it is understandable to want to engage in public displays of anti-racism. Nonetheless, we need to evaluate whether our posts are helpful, or whether we just want a pat on the back. Allyship is a sustained commitment to dismantling racist structures and institutions and requires effort even when no one is watching.

The centring of whiteness is less apparent in the example of calling out racism online. Calling out racism, and taking action against people who represent morally compromised views, is necessary to educate and hold people accountable for their racist expression. Yet it is sometimes confused with call-out culture (or ‘cancel culture’), the more aggressive method of public shaming and excluding the person as well as condemning their racist expressions. As a result, it can be scary to speak up and challenge ideas that we do not agree with. Nonetheless, we must get over this fear and accept the discomfort that comes with calling out racism and being called out ourselves.

Fear is an unproductive emotion which stifles thoughtful commentary about how to progress. For example, there is currently a debate among Newcastle students about renaming the Armstrong building. William Armstrong was complicit in the slave-trade, and some argue that someone with such a sinister history should not be celebrated. Others assert that we ought to keep the name while providing additional information about its history. These discussions are difficult, but are useful and necessary in establishing how Newcastle University will approach anti-racism moving forward. If we are too scared to express our views on such matters for fear of being called out or shamed, these nuanced and diverse discussions might not happen. However, we must not regard our own discomfort as more important than discussing and acting against racism.

Of course, our silence is usually not intended to cause harm or restrict progress. One might think that, instead of centring ourselves, we are being considerate and leaving space for others who know more. However, this is a failure to recognise our privilege in being able to speak out with fewer damaging stereotypes stacked against us than black people face. For example, white women’s testimonies are more likely to be taken seriously as they are not invalidated by the ‘angry black woman’ trope. Our silence can also lead to the expectation that black people must also take up the burden of anti-racism alone. It is, therefore, our responsibility to realise this privilege and use it to re-centre discussions around black lives and amplify black voices.

I want to highlight that all white people, including myself, are guilty of centring whiteness whether we are aware of it or not. Social structures are built on deeply-rooted white supremacy and racism. Dismantling these oppressive systems will not be easy. Sometimes, our opportunities to speak may be taken from us. This does not mean we are ‘victims’. Rather, it means we are sacrificing some of our privileges to leave space for black voices instead. And when we are given a space to speak, we need to be open to having difficult conversations that involve calling out others and being held accountable ourselves.

Finally, the most uncomfortable act of anti-racism: we need to reflect on how racism operates in ourselves and confront how our beliefs and actions contribute to the suffering of black people. Only when we stop centring on our feelings and start focussing on how we can improve and support the black community will notable change occur.