Dr Lisa Garforth is a senior lecturer and the Postgraduate Research Director for Sociology at Newcastle University. Recently, our colleague Audrey Verma and her collaborator JC Niala ran the Hope and Resistance in the Anthropocene symposium. They drew together interdisciplinary, intersectional and diverse papers to reflect not just on “life and loss in the Anthropocene” but also on “what sustains us and what it means in practice and theory to be citizens and humans in these trying times.” In the first of two related blog posts, Lisa links this with ideas from contemporary utopian theory. This post is based on a conversation with Natalie Partridge who transcribed it and helped frame the ideas.

One of the real pleasures of Hope and Resistance in the Anthropocene was hearing anthropologists, systems ecologists, biologists and many other researchers thread conceptual ideas about prospects for making better more-than-human societies and communities through their work. We heard from Matthew H. John about how concerns over the loss of natural beauty might stimulate better thinking about environmental challenges (‘Radical relationalities, possible futures: Reimagining experiences of beauty-of-place in nature’), and from Lyn Baldwin about using place-based learning and art to mobilise new forms of connection and care in relation to bee conservation.

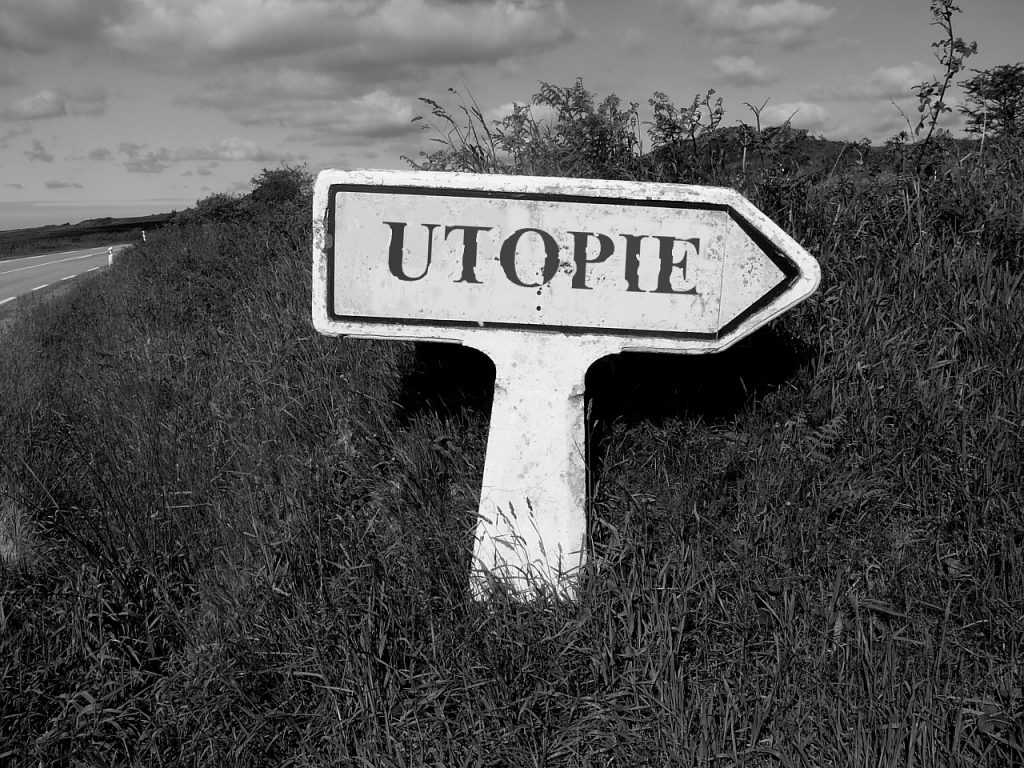

It was exciting to hear about projects looking empirically for hope for a better future and resistance to current Anthropocene realities. It can be helpful to think about these issues in relation to utopia – which I see as encompassing a range of cognitive and affective imaginaries and desires for things to be different.

Defining utopianism

I define utopianism broadly. It can include individual ideas and feelings that collective life can and should be different (however weak or fleeting). It includes more worked up visions of better collective futures, like formal utopian novels. In relation to politics, it can encompass the desires for change that so often infuse activism and social movements. And there are multiple social sites where people try to live everyday life differently that we can think of as utopian.

I find Ruth Levitas’s idea that utopia can be a method or hermeneutic helpful – a practiced and disciplined way of understanding social life oriented towards better futures. It’s a way of understanding the world rooted in everyday social experiences in worlds that are far from perfect. This method can also be taken up by social theorists trying to understand both how the world is and how it could be. That critical and creative tension between what is and what might be, between present and the future, is where utopia works.

Staying playful and creative

Often utopia is criticised as a way of trying to impose rigid social structures on people – blueprints and totalitarian regimes. At the other extreme it is written off as unrealistic and silly – daydreams and fantasies. Contemporary utopian theory celebrates utopia as process, journey and critique rather than endorsing specific endpoints and blueprints. Sometimes social scientists’ thoughts are either dismissive of utopia’s wild dreaminess and lack of realism or seek to domesticate it by only valuing realistic utopias. But for me, this risks missing the value of utopianism which lies in the playful, creative and excessive character of imagining otherwise – in its refusal of reality and realism.

This can and should often have an otherworldly or fantastical character. A creative refusal of realism is also often a moment of social critique, enriching the progressive imagination. Utopian visions can inform and enliven policy proposals. But you can’t reduce utopia to policy proposals – and policy proposals can’t and shouldn’t be utopian. So that raises the question of what utopia might have to do with sociology.

Speculative thinking in sociology

In my experience contemporary critical and qualitative sociology is primarily concerned with people’s experiences and struggles in current social circumstances. In the discipline’s formal origins, there was, by contrast, the ambitious confidence of Comte that it could predict and manage the future. We are rightly sceptical of this positivism now. In the post-war period critical social theories have maintained a broadly utopian interest in understanding contemporary social structures and dynamics by insisting things could be otherwise. But I share with Ruth Levitas a sense that sociology as a discipline has not often engaged with explicitly speculative thinking.

Levitas’s answer is to encourage sociologists and sociology to become overtly and committedly utopian, to get involved with imagining and describing proposals for better societies, not just exploring what is wrong with how we live now. She argues for a utopian sociology that would work in what she calls the ‘architectural’ mode – building and making visionary alternatives. But I am just as interested in a sociology of utopia, linked with what Levitas calls ‘archaeological’ utopianism, or the digging up and examining of utopianism in the wider society. Sociology – social thought, making critical sense of the social world that we’re in – is not constrained to professional or disciplinary practice. Undisciplined, creative, speculative sociologies can be infused with a utopianism and resistance to the real in ways that might complement and extend academic sociology in vital ways in the face of the climate crisis.