By Shannon Cowgill

Agnes de Castro is a play in which women hold all the power. Without women, none of the major events of the play would even happen. Okay…To put it another way, the plot is all set in motion because of Elvira’s inner green-eyed goddess, but with great power doesn’t necessarily come great morality!

As well as driving the plot, Elvira is able to manipulate the men around her into doing and thinking what she wants. Elvira’s power comes from identifying the weakness in others: she uses Constantia’s insecurity to convince her of Agnes’s back-stabbery, she uses the king’s love for his daughter to convince him of Agnes’s guilt, and she uses Alvaro’s love for Agnes to convince him to get revenge on the prince.

All in all, she’s pretty powerful.

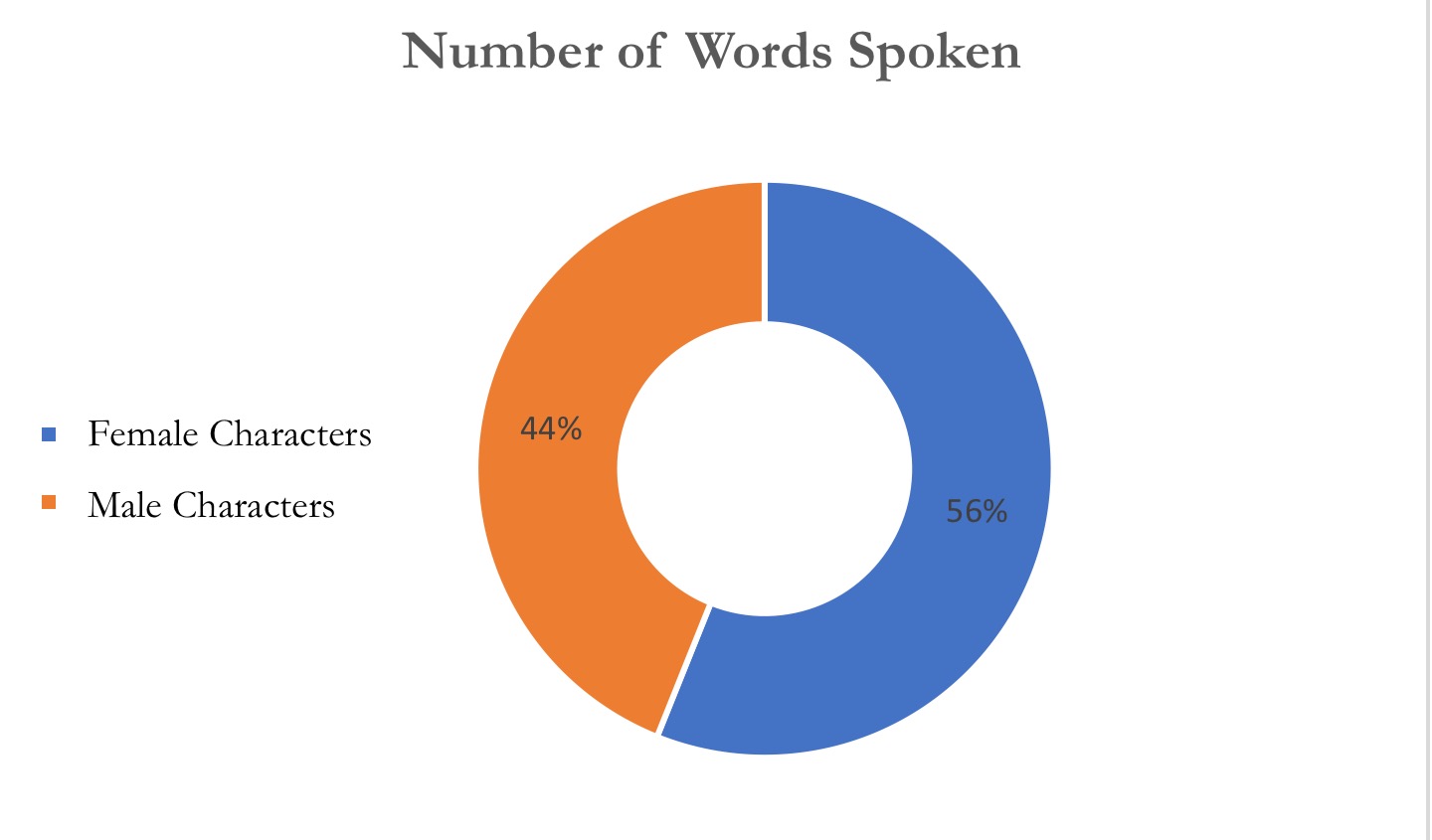

The power imbalance in the play is obvious in the amount of stage time and dialogue given to characters. The fairer sex are given more than half the dialogue in the play between just four female characters: God knows we love to chat! Even when the male characters do occasionally grace us with their presence, all they want to talk about is the girls anyway, thus maintaining a female presence on stage even when there isn’t a woman physically there. If there was a Bechdel test for men, Trotter’s play definitely wouldn’t pass it!

O.T.T: Sterotypes in the Play

The one disappointing thing about Trotter’s women is that they are so stereotypical. Trotter’s characters are laid out in extremes with ‘virtue, temperance and tenderness at one extreme […] power and violence at the other.’[1]

These extremes take the form of Elvira and Agnes, our chalk and cheese. Agnes and Elvira are the Jekyll and Hyde of the play:

- Elvira – the jealous ex; revenge-thirsty, scheming and manipulative.

- Agnes – the picture of innocence, pleased by obedience, a real Sandra Dee.

Oh, and let’s not forget that brief episode where Elvira goes all Lady Macbeth and becomes the hysterical woman after literally facing a ghost from her past.

BUT, there is still hope for women…

Although Trotter’s women are slightly stereotyped, they at least have more substance than the men of the play. Since all the men want to talk about is the girls – namely Agnes – we gain no real insight into their personalities. The only men who are given somewhat lengthy speeches (Alvaro and the Prince) speak only of Agnes. Plus, the two characters with the most power politically (the King and the Prince) aren’t even given names in the cast list.

Ultimately, it is the women of the play that we remember: it is a woman who drives the plot, it is a woman who is the title character, and although a man gets the final word in the play, he’s talking about … you guessed it … a woman.

Safe to say that for this play it’s women – 1, men – 0.

[1] Isabel Pinto, ‘Naturalising Politics and Metaphors of Loss: Forms of Sociability in Catharine Trotter’s Agnes de Castro‘, Luso-Brazilian Review, 53 (2016), 153-70 (p. 159).