The group was this week tasked with discussing the rather ominous topic of contemporary and Elizabethan readership. Conversation regarding our own reading experiences is all well and good, after all, but how can one truly get into the mindset of individuals who went about their lives centuries before our own? When reading through the Peter Stallybrass and Roger Chartier’s Reading and Authorship: The Circulation of Shakespeare 1590-1619, we identified several names of friends and associates of Shakespeare, with Sarah, Hannah and Phoebe tackling the various readers specifically and Jack deciding to look more in depth at the role of commonplace books for the everyday Shakespearean reader.

The Elizabethan Reader

So, you wake up after a somewhat crazy night out and come to the strange realisation that it’s the late 16th Century and, rather than the usual desire of cold pizza and several gallons of water, you feel a deep craving for something to read. Luckily for you, a gentleman called William Shakespeare has just released his first printed piece in the form of Venus and Adonis and everyone is picking it up. This is no upper class exclusive it would seem, and even schoolchildren are reading up, copying down excerpts into their books, so as to remember them and imitate their style in their later work.

You slowly realise this is one hell of a dream, and as you walk down the bustling streets you begin to understand how reading and learning hold a symbiotic relationship in this society – people are taught to imitate the work of those they read from, and to develop similar styles by repeating and reworking an amalgamation of writing styles, from the Bible to mythology to Shakespeare himself. Literature isn’t just picked up and read, it is enjoyed and assimilated by those with a passion for it. Much like the 21st Century, Drake is in the charts – though it is Francis, not Aubrey (and any relation between the two has as of yet not been established). Men, women and children alike are flocking to the theatres to see the latest plays, and the literature produced by the playwrights is easily accessible, especially poetry and prose (even in the 16th Century, Waterstones refused to stock much by way of scripts). With Venus and Adonis hot off the printing press, you muse to yourself who exactly read Shakespeare’s works before they were published for the first time.

Our story shall continue in the theme of a popular television show.

Patrons of Shakespeare

In early modern English Society, anyone perusing the arts or expensive hobbies often needed to look up the social hierarchy to find support in the form of a wealthy nobleman or noblewoman. Without these ‘patrons’ Shakespeare and his contemporaries would never have risen to fame or been able to publish and create as they did.

Below are examples of Courtiers who had a hand in aiding William Shakespeare’s work, these are there stories:

Henry Carey, 1st Baron of Hunsdon

Lived: 1526-1596

Connection: The Patron Lord of Shakespeare’s theatre group

Story: More recognisable through his appointed title ‘ Lord Chamberlain’ , a name also given to the group of actors he supported, Carey was responsible for reorganising Shakespeare’s groups after the period of plague in London in which theatres would close from 1592 until 1594. Shakespeare was after this period connected the the Lord Chamberlain’s acting troupes, until after 1603 when the group became the King’s Men.

William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke

Lived: 1580-1630

Connection: Served as Lord Chamberlain from 1615 to 1625

Story: As a poet, Herbert never gained much acknowledgement. However, as a patron of the arts and literature, William Herbert’s name was well known. With more works dedicated to him than anyone outside of the royal family in the early 1600s, including Shakespeare’s first folio of plays in 1623. There is some speculation to Herbert’s presence as the mystery man “Mr W.H.” in the 1609 edition of Shakespeare’s sonnets, as well as his likeness being the young man urged to marry in the collection – mostly due to his being junior to the bard and his refusal to marry English nobles.

Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton

Lived: 1573-1624

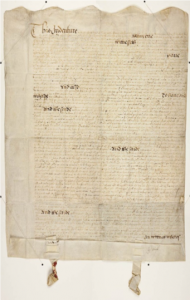

Connection: Patron of Shakespeare’s higher literary works during the plague years

Story: The Rape of Lucrece and Venus and Adonis were dedicated to Wriothesley, another suspected person to be identified as the youth of Shakespeare’s sonnets. The praise of the young earl in the dedication from Venus and Adonis was a blatant attempt to get his patronage. He succeeded in securing the patron, and doing so dedicated a second poem to Wriothesley. Richard the III and a revised edition of Romeo and Juliet would also bededicated to him.

Friends of Shakespeare

In this situation, it seems appropriate to take the words of another hero of British poetry and performance art in order to explain the nature of this list of people:

Friends will be friends,

Right til the end.

And much like Freddie, Shakespeare’s friends were some of his most important readers, as they would often receive circulations of his works before they were published.

Richard Burbage

Lived: 1567-1617

Story: As well as being a friend, Burbage was also a famous actor of the time and Shakespeare specifically wrote roles for him including Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello and King Lear. Burbage came from a theatrical family and even his father had built the first ever structure designed for plays: The Theatre, built in 1576. Shakespeare worked with Burbage as part of Chamberlain’s Men and performed together at The Theatre until they dismantled it and moved it across the Thames. Shakespeare and Burbage became business partners and re-named The Theatre as The Globe. The two men were great inspirations to each other with Burbage performing on stage for 35 years. The whole of London mourned his death at the age of 50 – his death even over shadowed Queen Anne’s. His grave stone simply reads ‘Exit Burbage’

Thomas Combe

Lived: 1589-1657

Story: Combe received a sword in Shakespeare’s will. The Combe family were close friends of William Shakespeare and were a wealthy family of landowners and lawyers. Shakespeare bought over 127 acres from the Combe family in 1602. Click here for more information about Shakespeare’s land buying in Stratford-upon-Avon. It is thought that the sword could have sentimental value to Shakespeare and had his son Hamnet not died he may have inherited the sword. Therefore, bequeathing the sword to Thomas may show great affection, indicating that he saw him as something of a surrogate son. Shakespeare was also good friends from Thomas’s brother, John Combe. The Epitagraph below is ascribed to Shakespeare as is supposedly about John’s ‘money-lending at 10 percent interest (the legal maximum at the time)’.

Ten in the hundred here lies engraved;

A hundred to ten his soul is not saved.

If anyone asks who lies in this tomb,

“O ho”, quoth the devil, “’tis my John Combe”.

Hamnet Sadler

Lived: 1562-1624

Story: Sadler was close in age to Shakespeare and his family lived near the playwright’s family in Stratford. The two friends married and had children around the same time too. However, they had very different careers: Hamnet inherited his father’s bakery which burned to the ground in 1595. Between 1580-99, Hamnet and his wife Judith had 14 children, 6 dying in their infancy. He also had a son called William who did survive. In 1594 and 1603 he was presented for baking household bread and cakes contrary to the statute, The Assize of Bread.

In 1608 he was also presented for having a muckhill in front of his house which annoyed the market traders. By 1615, his wife Judith had died and Hamnet was left with three children under the age of 18, differing heavily to Shakespeare who was making his fortune in London. However, the two friends grew up together and Shakespeare still thought of him as important enough to include in his will. Shakespeare’s twins Hamnet and Judith born in 1585 may be named after the couple. Shakespeare also left Hamnet Sadler 26 shillings to buy himself a mourning ring after Judith’s death.

Commonplace Books

Commonplace books are essentially just quote books; You know that collection of Oscar Wilde quotations that you’ve seen in Waterstones? The one you can buy for a quid, offering witticisms and judgemental comments that are hilarious but if you actually used one you would be seriously disliked. The type of book which sits by the toilet. Stacked in-between another quote book all about sex, (“The most fun you can have without laughing” and other such insightful quotations) which embarrassingly used to belong to your mother. This type of ‘low art’ belongs (just) above the 2003 Christmas Bestseller CRAP TOWNS, 50 worst places to live in the UK.

It will tell you ‘only dull people are brilliant at breakfast’, that ‘one needs misfortunes to live happily’ and that to ‘love oneself is the beginning of a life-long romance’. But what does this book, this illustrious collection of titbits made perfectly for that life affirming, if slightly narcissistic, trip to the toilet tell you about the early modern reader?

Well, quite a lot actually…

Just like the anonymous hero at Penguin Classics who would’ve researched, recorded and sorted each witticism into a real life book, so to would the early modern reader search for the best bits. Quotations from plays, poems and prose would be taken down, divorced from their context, they would commonly stand under topical headings or be presented ‘alphabetically or with an index to make specific passages easily retrievable’, as Stallybrass and Chartier state in Reading and Authorship. According to this text, the first book of this kind was published by Nicholas Ling and produced John Bodenham in 1597 (Politeuphia. Wits Commonwealth), with Bodenham releasing his second commonplace book the Bel-vedere, or, The Garden of the Muses in 1600. Shakespeare featured plenty, but, far from being the MOST FAMOUS playwright that ever lived in the plaudits of critics, he appears as ‘a canonical English poet in a bound volume neither through poems nor through his plays but rather through individual ‘sentences’ (of 10 or 12 syllables) extracted from his works’ (p.46). Following the rise in popularity of commonplace books, later editions of Shakespeare’s and other writers work would be printed and ‘marked’ in the scribblings of scholars and writers.

Although the same as our quotation marks, these symbols serve the opposite purpose. ‘Modern quotation marks serve to fence off speech as private property (what you say as opposed to what I say), whereas Renaissance “quotation marks” (which we will now call commonplace markers) note the passages that can and should be noted down by readers for their own reuse.’ (p. 47) Good writing then, was not merely considered genius, but reusably so. Likened by some as extracting honey or pollinating the flower, the popularity of commonplace books suggests that early modern readers were fans of a good quote, much like that one person on your Instagram feed who feels the need to remind you to ‘say it to my face’ when you have a problem.

Will you be like them, exchanging Shakespeare and rhyming couplets for arrogant truism’s, quoting Oscar Wilde when on the toilet? Maybe not. But know that Wilde believes in recycling just as much as the Jacobeans, he plagiarises too: ‘of course I plagiarise. It is the privilege of the appreciative man’. Perhaps, you should place Oscar Wilde on a bookshelf and away from the toilet? Maybe – and this is a big maybe – Hull shouldn’t be considered a Crap Town? Then again, maybe the commonplace book in our modern society really is just a book full of quotes?

So What Have We Learned?

Shakespeare’s readers came from all walks of Elizabethan life. Much like today’s society, the public would remember specific quotes of his work without necessarily knowing which specific piece they came from. Shakespeare was part of London’s popular culture, and as a result had many acquaintances within high society and the nobility of England . His friends and patrons were the benefactors of his fame, in cases benefiting from being so impactful on his rise to the top of English literature, where he would remain for centuries.

Above all else though, we can decipher Shakespeare had some pretty wicked birthday parties.

Well wow: this is a really well set out blog post, moving between your group discussion, and the imaginative idea of finding yourself in a dream-Elizabethan landscape, and somehow bringing in Law and Order into the mix too.

(As it happens, there was a vogue for dream-narratives where a dead author comes back to haunt the writer, telling them what to write on their behalf: see Henry Chettle;s “Kind-hart’s fream” or John Dickenson’s ‘”Greene in conceit: new raised from his grave to write the tragic history of Valeria” which even has a woodcut on the titlepage of the dead author, Robert Greene, writing in his winding sheet!

But I digress…)

I think this time-travelling idea is a great way to show that your group has understood the implications of the historical context (e.g. the patronage system, the education system) on the literary texts. Great use of illustration and hyperlinks too, to evidence your research for this blog.

I also think that you achieve a good tone throughout, I especially enjoyed the comparison of commonplace books to, ahem, bog-literature (‘enjoy’ is possibly the wrong word to use here, but you get what I mean) as a way to make us think about different reading strategies and motivations, reinforced by reference to Stallybrass & Chartier’s essay.

And thank you: I will now forever imagine Sir Francis Drake driving his crew nuts by singing “Hotline Bling” over and over…