One thing is for sure, and that’s that printing during the Renaissance was a meticulous system.

This week, our lectures and a visit to the Newcastle library archive have taught us a LOT about early modern books and their complex composition. In this post, I will first venture into the world of a professional printing work space, discussing step-by-step the process of turning an author’s manuscript from ink on a page to a real, saleable print. Secondly, I will discuss our trip to the library archives, comparing the books we looked at with contemporary examples and considering other useful information.

So…

There is no short answer to exactly how an early modern book was created. In fact and it’s important to understand just how much time went into each and every page.

Founded in the 16th century was Christoph Plantin’s printing company Oficiana Plantiniana in Antwerp, Belgium. It is now a popular destination for tourists and many visit the Museum Plantis Moretus for an insight into Plantin’s world of print and to see for themselves the exact process of his trade.

It houses the two oldest surviving printing presses in the world, that’s pretty cool. The equipment has been religiously preserved, giving it huge historical significance over other printing houses, especially in Europe.

Printing in the 1500’s was slow. The casting of the print types was perhaps the most time-consuming activity of all. Letters would be filed, chiselled, and punched into the end of a steel rod as seen below.

This is them hammered into a copper block, called a matrix, and an indentation of the letter is made.

The letter is then placed into a mold and molten metal is poured in to create the stamp. Lengthy process so far, huh?

By releasing a spring, the piece of type, which is also known as a sort, would fall and be ready to use. The process is then repeated. For some typecasters who were good at their job, as many as 4000 sorts could be produced in a day. That’s crazy! Additionally, particularly in Plantin’s shop, there was wealth of typecases (a tray storing the types) in the store room, with all manner letter types and fonts showing the diversity of options when printing the work. Of course this would be expected for as the fifteenth century advanced, so too did the demand for more books and the trade was under pressure to produce more and more; a movement Plantin’s store would have had no trouble with as the best in the business.

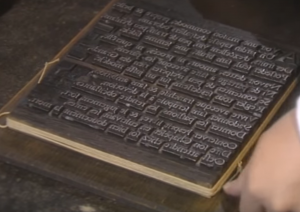

Moving on to the composition stage of producing a book. A compositor stick is used to collect the letters up into sentences and then these are placed in the correct order on a wooden galley (as seen below), just as they would look if they were being placed on a page, forming a composition.

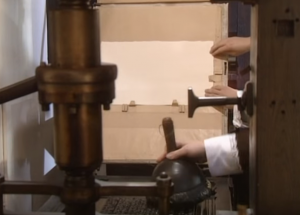

They are then placed on the stone of the press and secured tightly in a frame by using small wooden blocks. The text is inked using a leather ball filled with cording wool. The paper, which will have been moistened, is laid on the tympan which is the folden shut over the composition. This is then slid under the printing plate and by pulling sharply on the handle, the page is finally printed.

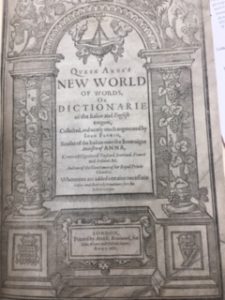

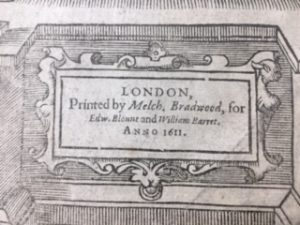

And there’s more much more to the process, but we might be here all day. Of course, in short, the pages must be put in order, pretexts must be added, a corrector will proofread the pages and finally, after mistakes have been corrected and re-proofed, the text will be complete, looking something like the photograph seen right.

The process is almost endless and incredibly repetitive. We were able to see first hand the kind of texts that were produced at this time and understanding the process beforehand made the trip to the archive all the more fascinating.

We agreed that seeing the printed books up close made us appreciate the labour involved in making each and every book and also the absolute necessity of every page being perfect. It seems that the aesthetic of a book was a top priority to printers and paratexts were highly significant (I’ll talk in more detail about paratexts in a later post). The ornate design shown in the picture would have been the first impression of the book and so these were highly significant in shaping a reader’s interpretations. This is because usually people would get the books bound themselves once purchasing them and this is why lots of first editions are dissimilar in the way they look.

As a quick colloquial sidenote, I absolutely loved handing these early books. The pages were so thick and the noise they made when turned was SO satisfying, we’re talking a proper crunchy ruffle. The pages are far more rigid than the floppy, seamless texture of a contemporary text. I felt like I was a printer holding my first product. They did smell super old and musty though which was the only negative as am a big fan of the smell of a freshly printed page.

So, books really were a work of art and dedication during the Renaissance. Modern books are practically showcased by their covers, hence our famous phrase ‘don’t judge a book by its cover’. Well, back in early modern printing shops, that was the last thing on the to-do list as the paratext was considered to be the exhibit of the author and the text within (example above).

Posted by Alex Grindle

A really detailed look at the process of printing, with great use of links and captions to the film. All of it goes to prove your point that the difficulty of this process, the amount of opportunities for things to go ‘wrong’ leads to every copy being unique, as one of your study group members pointed out in your group’s comments section 🙂

Bit of trivia: the ‘matrix’ the copper block that the type is made in, is another word for the womb (see OED: http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/115057?isAdvanced=false&result=1&rskey=wTdibP& )

A link to an Instagram account that you may like: Dr Johanna Green at Glasgow university posts images and videos of mainly medieval but also later books. In this video you can hear the crackle of the leaves being turned: https://www.instagram.com/p/BV7FkCVgNbq/?utm_source=ig_web_button_share_sheet

This is fantastic! I loved how thorough your explanation of the process was. In fact, I’ve decided I’m going to sack off university and go and work in a printing press!