PRODUCTION – PRINTING AS A LITERARY MODE OF PRODUCTION

- The international influence of printing houses upon Shakespeare’s printing process( Korea, Belgium, London) and the level of artisan skill which was involved. This influenced how we perceive books and early modern printing as scholars today.

- The process itself of printing, the evolution of such process during the 16th century, and how this influences the texts within them. For example, the order pages were printed on was not chronological (as I had originally presumed) and therefore explains some of the gaps in Early Modern texts, adding an interesting mode of production element to the study of Shakespeare’s plays. We also learnt that the “folio is the most expensive type of book because materials were more expensive than human production of printing”.

- We learnt about the commercial capital attached to print culture and printing shops for example, in St. Pauls, which allowed us to contextualise the First Folio and Shakespeare’s play scripts as products/artefacts as well as literary items.

Paratext

- How to use online archive websites such as the ESTC, ODNB and the EEBO to search for information regarding the various editions of books. The ODNB was useful for finding out further biographical details of the author. The information that I received from the ESTC informed my interpretation of the works contributors and contemporaries. For example, The Discoverie of Witchcraft by Reginal Scot provided scarce detail on those who contributed to publishing the work. Using the various websites it allowed me to find out more about the history behind the printing of The Discoverie of Witchcraft which was left out of the title page. Thus, I was able to find out other information surrounding the publisher Henry Denham and his contribution to other types of similar work.

- As well as this, looking at a physical copy of the text which has been passed through various owners we applied our study of annotations as paratexts. We scrutinised the annotations and noticed patterns in locations of notes that were placed in margins next to Bible references, suggesting a previous owner with Christian interests.

Authorship

The concept of authorship was radically different in the early modern period to our idea of it now. We learnt in week 4 that play scripts, let alone their authors, were not held in the same regard they are today. Published scripts were often sold without the author’s knowledge or permission. A playwright’s original script was less important to printers and publishers than the version of it closest to the one they and their readers would remember from stage performances. Without the publishing of scripts playwrights like Shakespeare and Marlowe would have almost no control of their plays. They would be performed year on year by companies that would adapt the stories to their performances, making the plays almost akin to stories told by word of mouth. In some ways this is understandable as plays would often be collaborative projects. Even if one author had written the original text, editors, civil servants in charge of censoring scripts would have a hand in altering them. Actors might improvise in their performances. Additionally publishers might add paratextual materials, make notes in the margins or even make corrections to the texts. Through these aspects of the theatre industry the authors relation to the finished product of a published script is less direct than it might be today.

Outcome

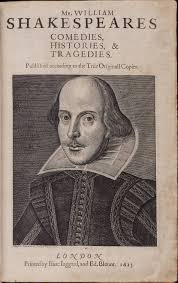

The various materials on printing that we have looked at over the last 2 weeks, will be very useful in relation to other aspects that we have observed over the rest of the module. We have better understood the printing process and the intricate thinking that went into these publications, in order to appeal to their targeted audience within the period, such as the order in which the plays were published in his ‘Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies’ introduction page. Keeping their targeted audience stimulated and entertained was obviously the priority of publishers, in a similar way that it was a priority for the Shakespearean company; the large variety of different plays on offer and the actors ability to play a variety of different roles parallels the importance of these respective intricacies. The various online archival websites that we have been given access to will also greater inform our understanding in the wider context of other materials we have observed. Furthermore, though not specifically related to the literal printing process, we have observed the fact that though writers such as Ben Jonson may have been rivals to Shakespeare, even they were able to appreciate his undeniable ability as a playwright: his respective praises include, “Thou art a monument without a tomb” and the “Sweet Swan of Avon”.

By Sarah Thompson, Olivia Varty, Ally Cloke, Guy Seddon

Well done, this is a wide-ranging blog post, well organised into subcategories to describe the areas in which you’ve strengthened your learning (production, paratexts, authorship) and in which you discuss both content and methodologies (e.g. archival work, use of e-resources). Not necessary for this exercise, but if (say) you were to use this as a basis of your part B assessment, you might want to choose one or two of these points, and go in more depth. You’ve already started to do so with your point on authorship, but as an example I’ll take one of the other sections: the paratexts. So you now have first hand experience from having looked at these in the archive, but in the reading for that week (Smith & Wilson on paratexts) you also have a bit more about the theoretical side of how these function. So you could move from a discussion about the archive visit, and combine it with what you learned in your private reading time. You could then link both of these points to your discussion about authorship, because the paratexts are the places where the ‘author’ is heard most clearly, either in their own voice to the reader or dedications to patrons, or in the way their work has been presented by friends writing commendatory verse.