Soso Ayika, Sophie Hamilton, Abi Dickson, Ellie Simmonite, Raveena Mehta, Leanne Francis

The first printing press in England was set up in 1476 by William Caxton. Its arrival enabled English printers to publish the early works of writers in quarto and folio form.

There were various stages involved in the publication of an early modern text. At the time, publishing industries consisted of printers, compositors, stationers, and publishers, each contributing to different stages of the printing process.

Printers manufactured the physical book, compositors worked the press, stationers bound and covered the pages, and publishers paid stationers license fees and provided printers with paper.

During the 1550s, some printers rose to popularity for their impressive craftsmanship and skillfulness. Christopher Moretus, a Frenchman who worked as a printer-publisher in Antwerp, was well known for his printing. At the height of his career, Plantin printed around 50 texts a year on at least 16 different presses. His work was symbolised by a golden compass around which the words ‘labore et constantia’ were written, meaning ‘work and persistency’.

Producing an early modern text required different tools.

Letters would be cut using files and chisels, with unreachable parts being removed by a negative punch. The punch creates the matrix in which the type was cast, then placed on a tray, inked and pressed onto paper.”

The printed pages were proof-read for mistakes made in production, such as incorrect grammar, punctuation or spelling, and would then be corrected.

Once this process was complete, the text would be ready for print.

Close Reading of Paratext:

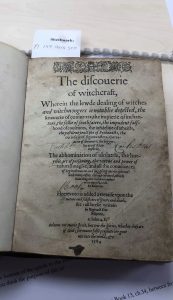

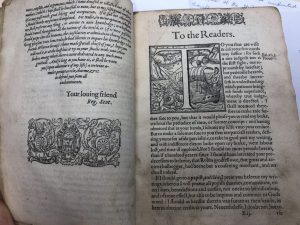

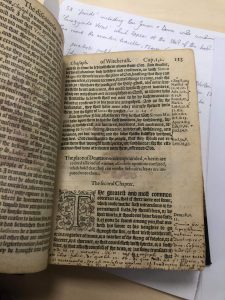

The Discoverie of Witchcraft title page is useful as it tells us the original owner of the book (Cuthbert Cockson) and tells us who the book was dedicated to. Throughout the text we see various examples of what looks like people practicing their handwriting, which suggests a lack of access to paper. We also see notes handwritten at the side of some of the pages whereby one of the owners of the book can make comments about it and express their opinions.

Helen Smith noted that scholars of the early modern period have questioned the historical authority of the author, arguing that “textual production was a substantially more collaborative process than is assumed by post-Romantic notions of the solitary genius” [Smith, P.8]. So essentially, paratexts are inevitable and will entail some sort of collaborative process be it from the printer, binder or reader themself.

Great use of the secondary reading by Helen Smith & Louise Wilson (you’re possibly the only ones to have done so!) plus the video from the Plantin-Moretus museum about the production process (though NB: it’s Christopher Plantin who’s the Frenchman who sets up the business, and then his Flemish son-in-law, Jan Moretus takes over). Some nice close-reading of the paratexts for the Discoverie of Witchcraft- were you able to decipher the marginal note on the page that you post at the end of this blog?