Archivist’s Log – 16th March 2382

I’d heard the stories. We all had. But I never thought I’d get to see one in person.

A real book.

Here at the Last Library, we are the proud owners of the world’s largest – and only – digital literary archive. Ever since the Great Media Purge of 2315 this has been the only place on the planet where members of the public are allowed, for a reasonable fee of just twelve million credits, to read books. From the great plays of William Shakespeare to the classic novels of Stephenie Meyer, from the ancient epics of Homer to the rhythmic poetry of Jay-Z, those with a keen enough interest and a large enough wallet can peruse a vast digital library of works, all available as instantaneous mind-uploads. Here, you can absorb the entire literary canon in the time it takes to say “Ah, now I see why this costs twelve million credits”.

My job as chief archivist is to maintain the collection of works here by ensuring that any new books which arrive at the library are scanned into the database and backed up to the cloud (by “the cloud”, I of course mean High Overlord Nimbus, the sentient alien storm cloud who took over the world last Thursday… again…) Sadly, in all the years I’ve worked here, not a single new book has arrived for me to scan. Until today.

When I woke up this morning and stumbled downstairs to the lobby, an unmarked parcel was sitting invitingly on the doorstep. Given that company policy when encountering a mysterious package is to return it to High Overlord Nimbus (he probably dropped it by accident and would really like it back), I decided company policy didn’t apply to me, and tore open the package to see what was inside. I felt like a kid on Christmas morning, as they used to say in the old days, back when Christmas wasn’t banned for being “too fun”.

Inside the package was an ancient artefact I’d always dreamed of holding in my hands. A book. A real one! I couldn’t believe it. It was just like I imagined, except a lot smaller and dustier and not as shiny and mostly falling apart and not really anything like I’d imagined at all. But it was still fascinating. The book was titled “Sixe Courte Comedies”, by John Lyly. It consisted of a series of synthetic leaves bound together, made from what they used to call “paper” (note: tastes very strange, do not eat), a thin, flexible material apparently made from wood pulp. They chopped down trees just so they could read books! No wonder the only rainforest left is kept in a vault on Mars.

Upon each leaf of paper was text, much like the text you’re reading right now, except it wasn’t on a screen; it was physically imprinted on the very fabric of the book. You couldn’t edit or delete it, it was permanent. So permanent, in fact, that it’s lasted hundreds of years, unlike this log which will be instantly erased once read. According to legends, words were printed onto books using a dense black liquid known as ink, presumably harvested from the local octopus farm. This ink substance is what they used to write with. They say anyone could pick up a “pen” (an instrument filled with ink) and write whatever they wanted – you didn’t even need a licence! But this was not mere penmanship. Every letter was precise, uniform, like a font. But how was such uniformity produced? I accessed the database to research the matter, and found some intriguing information on the subject. Apparently, those who produced books in this period used printing presses: huge hand-operated devices which would press a board of raised letters covered with ink onto the sheet of paper. An ingenious invention by Johannes Gutenberg, Moveable Type allowed printers to reorder letters as needed for each sheet. Each letter was assigned to an individual leaden tile, and these tiles were arranged by hand to create words (like in the ancient mental aptitude test known as Scrabble).

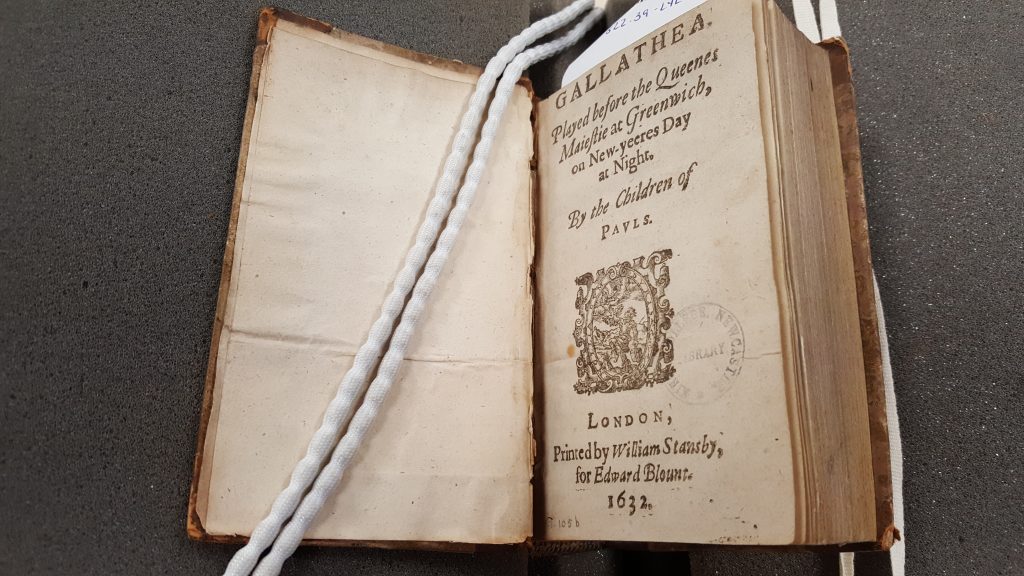

As I read through the book, I noticed that before each play was a title page, marked by the printer’s seal: an image of a jaunty fellow lifting a feathery bird up to the heavens. They say pets look like their owners, and that is very much the case here, as the man’s hair bears a striking resemblance to a dead seagull. Along with this peculiar picture is the date of publication (1632) and place of publication: London! That’s where my great-grandparents lived many years ago, back before Great Britain left the Galactic Union and took off into the sky, never to be seen again. This page also tells us that the volume was printed by William Stansby, for Edward Blount. In other words, Stansby did all the hard work and Blount took all the profits. Reminds me of my working relationship with the High Overlord. Not that my work is particularly hard… or particularly work, come to think of it.

The main title page states that these plays were “Often Presented and Acted before Queene Elizabeth, by the Children of her Majesties Chapell, and the Children of Paules”. I have simplified this text here for your convenience, as in the original many of the S’s are elongated, so that they appear like F’s. I can only assume that this must be because everyone back then spoke with a lisp. Also presented here is the author, “the only Rare Poet of that Time, The Wittie, Comicall, Facetiously Quicke, and unparalleld John Lilly, Master of Arts”. I presume they ran out of space to add “exceedingly modest” to that list. There is also an undecipherable phrase in a strange language I cannot find any examples of in my database: “Decles repetitia placebunt”. Perhaps this is an example of a “dead” language, only studied and known by the erudite and wise (i.e. not me.)

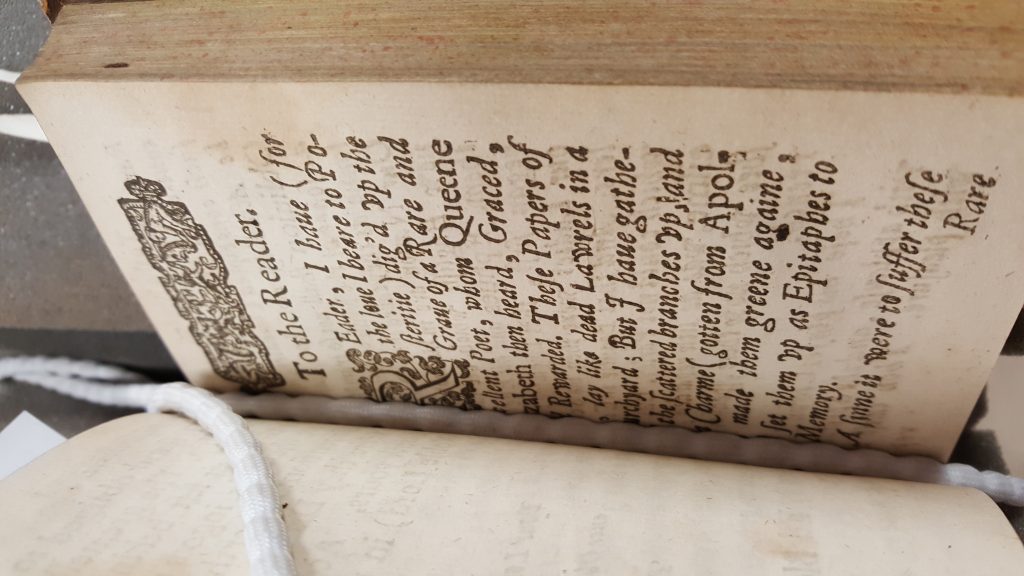

As I continued to read through the book, my train of thought was suddenly halted by an introductory message to the reader, which for some reason had been placed directly in the middle of the book! At first I thought this was a mistake, but perhaps this is not the case after all. According to my research, those rich enough to purchase books (which were only moderately cheaper than visiting this library) could ask for custom bindings, allowing them to select their own cover for the book. Some of these binding services may also have allowed the customer to re-order the pages; perhaps the owner of this volume wished for Gallathea to come first in the order of plays and asked for the sections to be rearranged, hence the dedication to the reader being in the middle of the book rather than at the beginning. This would also explain why the signatures at the bottom of each page (which were designed to allow printers to fold the sheets correctly) are in the wrong order, starting with P instead of A.

The dedication to the reader is written by Edward Blount, the thieving capitalist who stole William Stansby’s hard-earned cash via illicit methods such as “being his boss” and “owning the printing company”. In the dedication, Blount admits to more heinous crimes, such as grave robbery: “I have (for the love I beare to Posteritie) dig’d up the grave of a Rare and Excellent Poet”, animal cruelty: “a shame, such conceipted comedies, should be acted by none but wormes” and most despicable of all, recycling: “I have gathered the scattered branches and by a Charme (gotten from Apollo) made them greene again”. Seeing such morally repugnant actions being encouraged made my skin crawl. I simply could not stand it. Therefore, with tears in my eyes, I threw the object which I had yearned for my entire life directly into the incinerator. Luckily, I had forgotten to switch the incinerator on, which was a relief when I changed my mind a few moments later, and rescued the book from its infernal fate, squeezing it tightly in my arms like a newborn baby (note: do not squeeze newborn babies too tightly unless you enjoy the feeling of milky vomit trickling down your shoulder). I decided not to scan the book into the database: it was too precious to share. I took it upstairs to my living quarters, and smiled at the witty writing, the masterful printing, and the funny long S things.

Message ends. This blog post will self-destruct in 3… 2… 1…

Lyly, John. Sixe Court Comedies (1632)

By Patrick, Polly, Zoe, Gabs, and Alex.