Abi, Ellie, Leanne, Soso, Raveena & Sophie

As a group we learned many things about early modern printing and the printing of the first folio. While all of us carry around books on a day to day basis, we’d never really considered the complexities that go into making them, especially for early modern printers in regards to folios and quartos – folding paper in the lecture was hard enough for us so it really brought an appreciation to the process. One of the most interesting things we also considered as a group was when we considered what was in Shakespeare’s first folio in comparison to what had previously been published. Shakespeare’s first folio contained around 18 new plays, including Macbeth and The Winter’s Tale, which was surprising considering those are two of his best known plays.

Something we also found surprising was that, though the paratext claimed Shakespeare’s folio was complete, and that all other copies of his plays were pirated (“stolne, and surreptitious copies, maimed, and deformed”), the catalogue was actually incomplete. Troilus and Cressida does not appear in the catalogue but is included at the very end of the folio, which suggests there may have been an issue with getting the printing rights for the play, and so it was added in at the end just before the folio was published. The folio does not include the plays Pericles and The Two Noble Kinsmen, perhaps for the same reason, or possibly because these plays were created in collaboration with other writers.

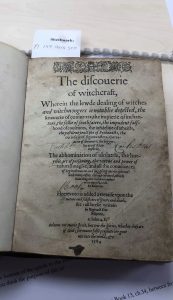

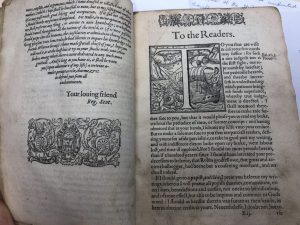

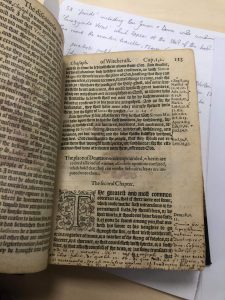

Learning how to interpret the paratextual content for various collections, such as The Discoverie of Witchcraft, which we looked at in the Robinson Library, has enabled us as a group to understand early modern printing on a deeper level. The paratext in early modern books was often used for different purposes: to introduce the text, market the book, and provide information on the publisher. Moreover, in our study of early printed works, we also examined annotations placed in the margins of primary material, which sometimes alluded to ideas of censorship or previous ownership. We learnt that all of this information, which we sometimes overlook as readers, is vital to our understanding and interpretation of many older texts.

By observing secondary sources on paratexts, such as the documentary ‘The Secret Life of Books’, which shows how the language in the paratext of Shakespeare’s first folio was most likely a marketing ploy due to its use of imperatives and emphatic language, we have discovered just how influential the prefatory material can be. The documentary also suggested that Shakespeare’s works weren’t entirely his, but made in collaboration with others. This came as quite a surprise, since the general impression of Shakespeare was that he was responsible for all of his work.

As a group, our approach to reading has changed dramatically. The importance of examining source texts in great detail, with a thorough approach, is now something we all wish to take onboard for each of our different modules. Our long term goal is to approach each new text with great scrutiny, considering the meaning and hidden clues behind paratexts. After learning the intricate and time-consuming process behind the ‘moveable type’, which enabled us to have access to so many of Shakespeare’s plays, we are now even more appreciative of early printed works. This module has taught us how to interpret older – and even newer – texts but also the value of the early printing process.