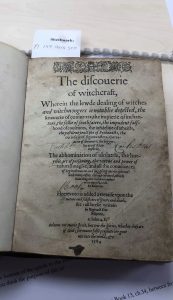

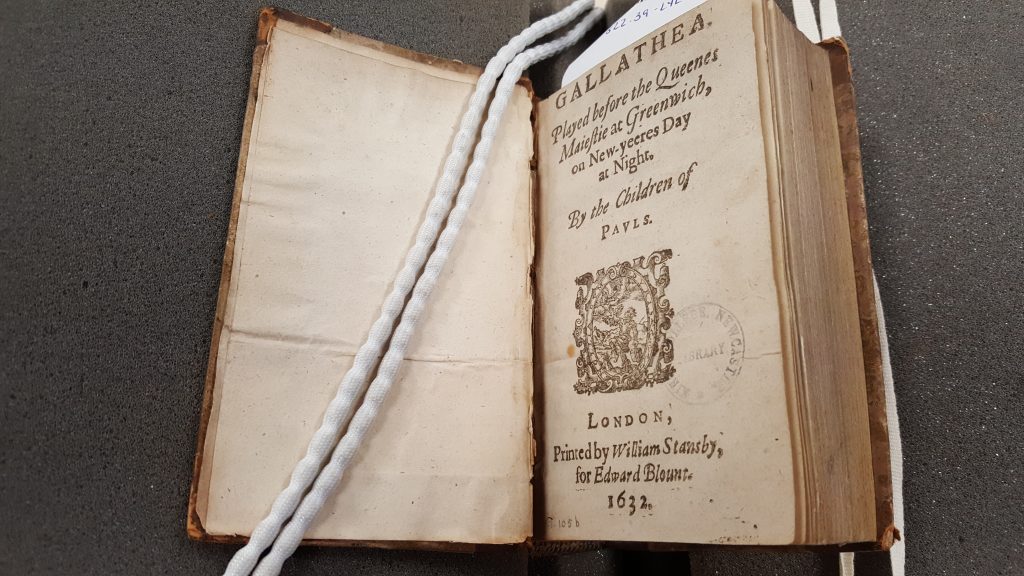

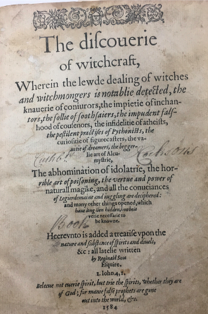

The Discoverie of Witchcraft, Reginal Scot, 1584, PI1599614

Printed in 1584, the first edition of this book provides very little detail on how it actually came to light. Albeit presenting the author’s name on the title page, other information appears to be surprisingly absent. Neither location of print or printer’s name are included, possibly because, as clarified by the ODNB page on Reginald Scot, the work was published without a licence. I would speculate however, that the controversial topic may have also played a role in the publisher and printer – identified as William Brome and Henry Denham (EEBO) – wishing to conceal their identity and involvement. This view could also be supported by the emphasis on justifications that is present throughout the book. The title page includes a bible quote, which could easily be interpreted as the author attempting to connect his claims with a divine purpose. By including this verse, Scot compares his writing to a quest for the truth, focused of exposing “false prophets” – specifically witches and magicians – as liars. However, the biblical reference also functions as a defence against censorship and critics, concept which is later repaired during the dedication to the author’s patrons.

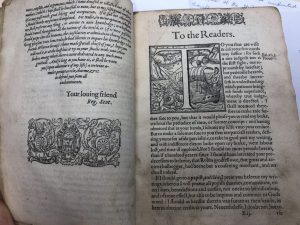

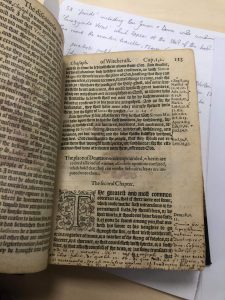

Overall, the text is dedicated to four people – excluding readers – and all the dedications seem to navigate the thin line between praising the individuals dressed and asking for their mercy. Scot directly writes to his cousin – his financial backing, for lack of better words – and to three additional contemporary figures: Sir Roger Manwood Knight, Lord Chief Baron of the Majesty’s Court, a judge, asking for his comprehension in reading his book, and Doctors Coldwell Deone of Rochester and of Canterbury, asking for their courtesy and understanding. The topic itself, considering the context, seems divisive. the early modern population seems to have had very clear concepts of witchcraft as being a human manifestation of the devil, and a work which attempts to debunk these views could easily be interpreted as going against both religion and kingdom and promoting blasphemous and deviant behaviour. Scot’s work, after all, presents arguments that go completely against works like the Démonomanie of Jean Bodin (printed 4 years before) and even the views of King James VI (who later published a work which claimed to denounce witchcraft as a true malevolent practice and directly mentioned and headily critiqued Scot’s views).Not many copies remain of this first print, however, the existing documents provide some evidence of their “provenance” in the form of different inscribed signatures or initials and underlined sections throughout the text. Additionally, evidence present in other texts suggests that Scot’s work was well known: as explained in the ODNB entry, Scot “was very widely read in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries”, with other authors referring to him and his Discovery in their works or seemingly using it as reference material. Despite its unlicensed beginnings therefore, The Discoverie of Witchcraft had a substantial role in the early modern world, passing from hand to hand and having been taken under consideration by a number of Renaissance figures.

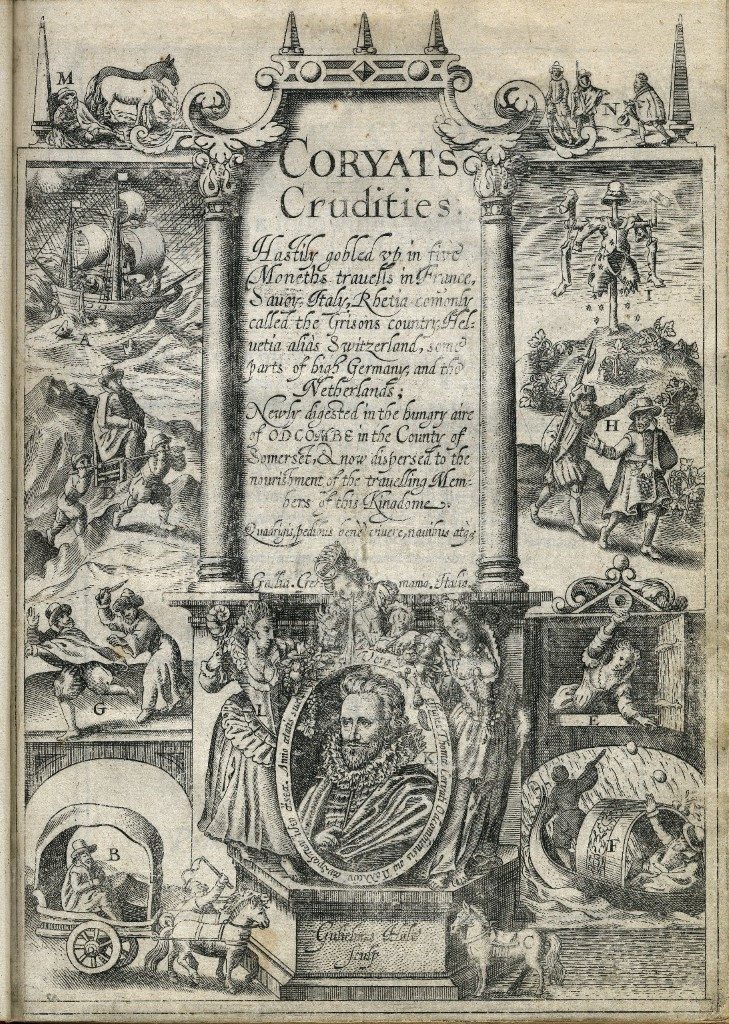

Thomas Coryat’s Coryat’s Crudities (1611)

The most obvious paratext seen in Coryat’s epynomous travel account Coryat’s Crudities is the elaborate title page. Each of the many illustrations on said title page are numbered, with each number correlating directly to a chapter in the account. Each illustration is extremely intricate and a print of a metal engraving, allowing for elaborate and fine detail. A further paratext is the ‘key to the title page’ (A1R) which follows the aforementioned illustrations, and gives a summary of what each chapter entails. This is then further reiterated in the following paratext, a second ‘key to the title page’ which summarises the initial description in rhyming couplets. One of the most interesting aspects of the 1611 copy of Coryat’s Crudities is its evident provenance, with a previous owner making notes in the margins drawing attention to particularly favourite lines, and asking questions as to what they mean.