Aidan Beck, Lecturer, Newcastle University Business School

What did you do?

Newcastle University Business School was asked to collaborate with North East Times and PwC on a research project called “NET 250”, initiated by Fiona Whitehurst (Associate Dean Engagement and Place) and Sarah Carnegie (Director of Employability). PwC are a multinational organisation offering professional services, and one of the “Big Four” accounting firms, whilst North East Times are a local media organisation who showcase businesses in the region through their business publication. This was therefore a significant project to be involved in, working with two major stakeholders.

The “NET 250” project aimed to highlight the top 250 companies by revenue in the North East and celebrate the success of business in the region through a high profile awards event hosted by North East Times on 14th May 2025 at Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art. The output of the research project was also included in the May 2025 edition of the North East Times’ “N” magazine. The event was attended by over 200 people [1], which included many business leaders and senior personnel from organisations around the region.

My role was to act as the project lead and supervise four students who were recruited for paid work between October and December 2024 as partners in research for the project. The students, because of the agreed scope of the project and the criteria for a company to be eligible, were required to research several datapoints for many companies in the region.

Students used publicly available information, financial databases and Companies House to gather the information and documented their work in a spreadsheet. This spreadsheet was then used to compile the final list of 250 companies which was refined and agreed by North East Times, PwC, Fiona Whitehurst (Associate Dean Engagement and Place) and myself.

The output of the students’ work was therefore crucial in the production of the final list of 250 companies which was revealed at the “NET 250” awards event and published in North East Times’ “N” magazine.

Who was involved?

Aidan Beck (Lecturer in Accounting & Finance), collaborating with those who are responsible for impact and engagement at Newcastle University Business School, working in a cross-school partnership.

Four students – consisting of two postgraduate and two undergraduate students from a mixture of international and home, and each studying a different degree programme (MBA, MSc Economics and Finance, BSc Economics and Business Management and BA Business Management).

How did you do it?

The four students were recruited following an application process which first required the submission of a CV and a cover letter which highlighted relevant experience for the project, for example their ability to work in a team, experience in using financial databases and analysing financial data. A shortlist of candidates was then compiled, and interviews were held in October 2024 with senior managers in the business school.

An initial briefing meeting was held towards the end of October 2024, during which the students were briefed on the project timeline and their role as well as engaging with and agreeing the scope and approach with PwC, who also attended the meeting.

Following the initial briefing, the students then worked independently and managed their own time around their university commitments to undertake the research. They used financial databases and publicly available information to gather the data, and then used Companies House to ensure the key data required was factually accurate.

Although revenue was the key metric, there were several additional criteria to consider and data required to collect to ensure the agreed scope was followed, and accurate data documented. These included whether the company has significant decision making and obvious presence in the region, the date on which accounts were submitted to Companies House and whether the company was a subsidiary or related company of another within the list.

I met weekly with the students throughout the research project (alternating between online and in-person) to discuss the students’ progress, investigate any anomalies identified and answer any questions they had.

Following the completion of the students’ work, I performed a comprehensive review of the list, submitting to PwC in January 2025 for the data to be verified. Subsequently, meetings were held in 2025 with North East Times, PwC, Fiona Whitehurst and myself to refine and agree a final list.

Did it work?

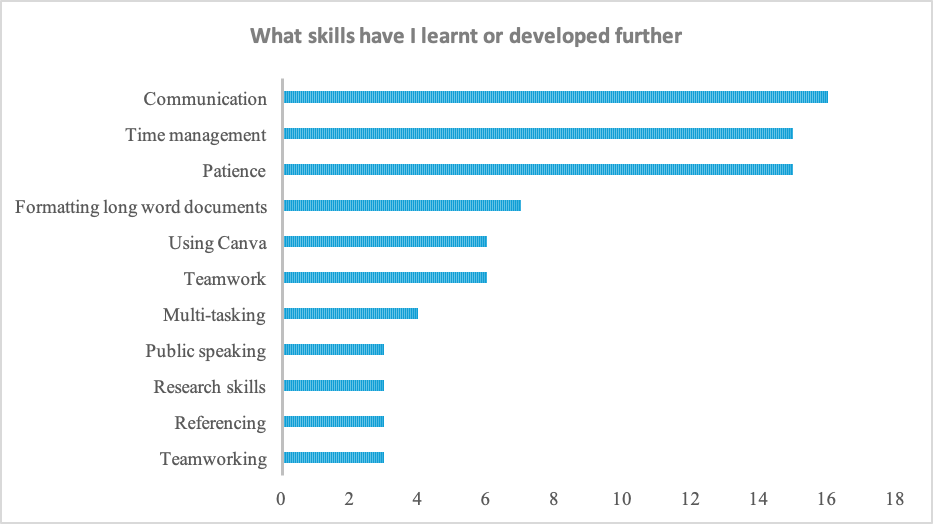

Overall, the project itself was a success, with the students describing it as a challenging and rewarding experience and one which has developed their critical thinking, teamwork, data research and financial analysis skills. Developing student skills as researchers is increasingly important as they progress through their studies. The “NET 250” project will therefore help improve student engagement with research as part of their studies.

In February 2025, two press releases were published[1][2] which launched the “NET 250” campaign, outlined its scope and mentioned the students and staff at Newcastle University Business School involved. The same people were then named and thanked at the “NET 250” awards event and in the editor’s welcome of the May 2025 edition of the North East Times’ “N” magazine. Not only does this highlight the appreciation and value of the efforts of the students and colleagues involved but it is also positive for Newcastle University Business School to be a key partner for a project which has real meaning and significance for companies across the region.

Engaging in this type of project requires considerable effort from both the staff involved and the students, especially when the project is a new venture for all those involved. As the project leader and supervisor of the students, I had ultimate responsibility for how the project was run, dealing with any performance issues and both the quality and accuracy of the research output. Furthermore, my role was to support the students and coordinate the team, review the students’ work and liaise with the key stakeholders (PwC, North East Times). With the students all studying on different degrees, a logistical challenge was making sure everyone was free at the same time when organising meetings. Additionally, engaging closely and regularly with the key stakeholders and Fiona Whitehurst (Associate Dean Engagement and Place) was important firstly to ensure the project scope was followed, but then secondly to refine and finalise the “NET 250” list.

This type of project was new to me as well, so the support and guidance of those more experienced in engagement activities at Newcastle University Business School, was equally important to the success of the project.

In terms of the students, because this type of research project was new to them, they required support and guidance throughout the project from myself as project leader. In addition, the project was extra-curricular, which meant the students had to balance the workload of the project with their independent studies, assessment commitments and timetabled activities, whilst working to a challenging project timeframe.

In conclusion, through working with two important stakeholders (PwC and North East Times), the press releases, the “NET 250” awards event and the publication of the research output in the May 2025 edition of the North East Times’ “N” magazine, this project has been both significant and impactful within the North East region. It has been beneficial for the students’ development and the School’s reputation. The project has also helped develop my scholarship and engagement, in addition to inspiring me to adapt this type of research into the classroom in the future, through experiential learning (which is discussed in the next section).

Next steps?

As mentioned above, some of the benefits gained by the students were critical thinking, data research and financial analysis skills. As a result, I would like to integrate this learning into other areas.

For example, I plan to incorporate a variation of this research process into a non-specialist accounting and finance module, whereby students, playing the role of business managers, can use financial databases and publicly available accounting information to evaluate the performance of businesses, in comparison with its competitors and other key companies within the industry.

The objective of this is to adopt experiential learning by using real-world examples and financial databases to increase accounting literacy and highlight the importance of accounting information for those in business who aren’t accountants.

The Graduate Framework

This project helped the students develop the following skills from Newcastle University’s graduate framework:

Engaged – the students were all fully committed to the project, working hard throughout and were receptive to feedback.

Collaborative – the students had to work flexibly to a challenging timeframe, around their existing University studies, and ensure they communicated queries and findings clearly.

Curious – the students applied a questioning mindset throughout the project, always keen to learn more about accounting information and often asking “why.”

Digitally Capable – the students utilised publicly available information, financial databases and Companies House to gather the required information.

[1] https://bdaily.co.uk/articles/2025/05/14/the-net-250-the-north-easts-top-250-businesses

[3] https://www.ncl.ac.uk/business/news/school-partnerships-with-net/