Sarah Carnegie, Senior Lecturer, Newcastle University Business School

The 40-credit capstone module, BUS3053, Management Consultancy Project is available as an option to students on Business Management, Marketing and Management and Accountancy and Finance undergraduate programmes. The module can be characterised as an example of work integrated learning (WIL) as it is “embedding learning activities and assessment that involves students in meaningful industry and / or community engagement” (Jackson and Bridgstock, 2021, p.726). In each academic year the students from these programmes are allocated to small teams, ideally 8 in each team, to engage with an external client. Each client is assessed by the School as having a suitable business issue or problem for the students to tackle and therefore provides an authentic, live work experience (Dollinger and Brown, 2019).

The value of WIL is widely appreciated in existing research with positive outcomes including, supporting student capacity to take responsibility for their work (Caldicott et al., 2022), fostering work values and human capital (Ng et al., 2022), and developing a range of skills such as teamworking, communication and critical thinking (Jackson and Bridgstock, 2021). Additionally, the importance of developing professional readiness has been noted (Jackson and Bridgstock, 2020, Jackson and Tomlinson, 2022). Whist definitions of such readiness will vary depending on career direction, it is acknowledged that students require certain common skills, so they can “emerge as professionals; navigate relationships with others; and build their sense of self” (Caldicott at al., 2022, p. 388).

However, are modules such as BUS3053 truly offering opportunities for students to achieve these positive outcomes? In May 2024 the Institute of Student Employers (ISE) highlighted that the gap between employer expectations and graduate behaviours is widening. Just under half (49%) of employers reported that graduates were career ready at the point of hire (a decrease from 54% in 2023). Whilst there may also be an extent to which employers lack understanding of the student experience, concerns about how well students understand what life beyond university will be like and have developed the necessary career skills to navigate this, have been voiced for some time (Bridgstock, 2009). What impact can such modules have in helping students apply their learning and development of skills in workplace environments?

This module includes a 2-hour ‘celebration and reflection’ event is scheduled for the week following the submission of the outcomes of their group work; the Client Report (40%) and Client Presentation (10%). This event is designed to encourage active reflection and support the remaining 50% of the module; an individual reflective assignment. This assignment asks the students to discuss the learning gained from the module. As Ryan (2013, p.144) states ‘learners are not often taught how to reflect’, so the intention of the event is to provide a relaxed and informal opportunity to think and talk about what they have experienced working on the module.

During the ‘celebration and reflection’ event the students sit with their team colleagues and are provided with roughly divided sheets of flip chart paper and a range of coloured pens, markers and highlighters. They are asked to draw or comment, however they wish to, in response a series of questions about what they have learnt, with at least 10 – 15 minutes being allowed for chatting and sharing of thoughts. As Lengelle et al., 2016, p. 106) comment good reflection should be “stimulating a playful, creative process that fosters a sense of fun and competence”.

At the event held in March 2025, students were asked to reflect on various elements of their experience on the module including two specific questions,

- ‘what skills have I learnt or developed further (during the project)?

- ‘what have I learnt about being a professional (during the project)?

Student self-identified, in pictures or words, particular skills and learning points.

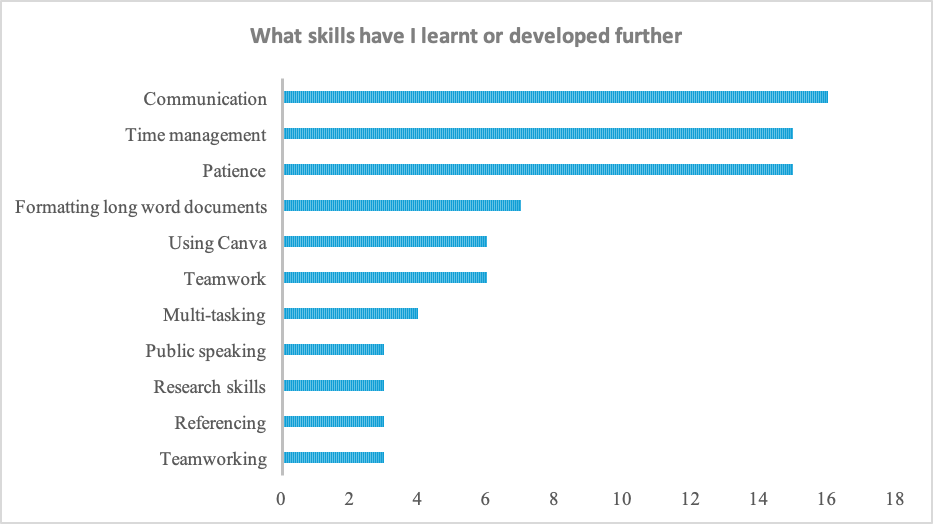

The results from the 30 students who attended to the question ‘what skills have I learnt or developed further’ were:

Figure 1 – Skills mentioned more than 2 times

The responses from the 30 students who attended to the question ‘what have I learnt about being a professional’ were more wide-ranging. The responses have been categorised as follows.

Responses focusing on specific practical skills,

- Email – 16 mentions related to setting up email signatures, email etiquette, drafting professional emails and learning email ‘dialect’

- Planning – 6 mentions related to project planning, drafting plans and schedules, and setting up invites for meetings using Teams

Responses focusing on workplace behaviours,

- Attending meetings – 10 mentions related to being punctual, preparing for and attending meetings

- Personal attributes – 9 mentions of personal attributes such as taking initiative, resilience, respect for others, leadership and perseverance

- Managing work – 8 mentions related to delegating, taking responsibility, problem solving and managing deadlines

- Developing social capital – 4 mentions of networking

Figure 2 – Student representations of skills and attributes

The responses provide insights into how the students understand ‘skills’ and ‘being professional’, with both practical functional skills and personal attributes and behaviours being described for both. It is interesting that ‘patience’ has been reported as one of the main behaviours learnt, ranging to what could be considered an everyday practicality of how to ‘email’, also highlighted by a significant number of the students.

The reflections illustrate that the module is helping students to become career ready in a holistic way. They can recognise specific skills they have learnt and have gained an awareness of what will be required of them in a professional work environment. The module provides a relatively ‘safe’ space where they have to quickly learn relevant skills and appropriate professional behaviours to be able to engage with their clients. However, we can also consider how some of the skills highlighted could be integrated earlier into their learning and assessment, so that some of the more everyday practices could be embedded earlier, so they can focus on developing their deeper workplace interactions with clients with more confidence.

Reference List

Bridgstock, R. (2009) The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: enhancing graduate employability through career management skills, Higher Education Research & Development, 28:1, 31-44,

Caldicott, J., Wilson, E., Donnelly, J. F., & Edelheim, J. R. (2022). Beyond employability: Work-integrated learning and self-authorship development. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 23(3), 375.

Cunliffe, A.L. (2016) Republication of ‘On Becoming a Critically Reflexive Practitioner’, in Journal of Management Education, Vol 40(6), pp 747 – 768.

Dollinger, M., and Brown, J. (2019). An institutional framework to guide the comparison of work-integrated learning types. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 10(1), 88–100.

Institute of Student Employers (2024) Is career readiness in decline?https://ise.org.uk/knowledge/insights/195/is_career_readiness_in_decline Accessed 30/05/25

Jackson, D., and Bridgstock, R. (2021). What actually works to enhance graduate employability? The relative value of curricular, co-curricular, and extra-curricular learning and paid work. Higher Education, 81(4), 723–739.

Jackson, D., and Tomlinson, M. (2022). The relative importance of work experience, extra-curricular and university-based activities on student employability. Higher Education Research and Development, 41(4), 1119–1135.

Lengelle, R., Luken, T. & Meijers, F. (2016) ‘Is self-reflection dangerous? Preventing rumination in career learning’, Australian journal of career development, 25(3), pp. 99–109.

Ng, P.M.L., Wut, T. M., and Chan, J. K. Y. (2022). Enhancing perceived employability through work-integrated learning. Education & Training (London), 64(4), 559–576.

Ryan, M. (2013) The pedagogical balancing act: teaching reflection in higher education, in Teaching in Higher Education, Vol. 18, No. 2, 144-155.