In the agricultural calendar, September is the time for reaping:

September, welcome! Month of genial mood,

To hearts that crush’d in life’s tumultuous press,

Pant for the rural paths of peacefulness,

On which the world’s cold gaze may not intrude.

The calm that wraps the earth, and sky, and sea,

Permits the mind its own dear fancies bright;

And, as in lone seclusion of the night,

The past revives and glads our privacy.

What jovial train breaks on us as we muse?

The reaper bands ‘mid fields of bending grain,

Where mirth’s loud shout, sly joke, and winning strain,

The light of joy, through deep stirr’d hearts diffuse.

Blest scenes of youth! And happy harvest hours!

Life has no equal charms – no bliss like yours. – MS.

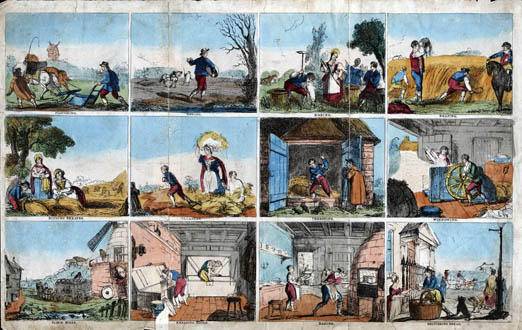

The above image is a detail from a larger illustration depicting the bread-making process all the way through the cycle from ploughing the fields to delivering loaves (seen below).

The stages shown here are: ploughing, sowing, hoeing, reaping, binding the sheaves, gleaning (i.e. gathering the corn which has been left in the field after reaping), threshing, winnowing (i.e. separating the chaff from the grain), flour mills, kneading the dough, baking and delivering bread.

The date of this illustration, and the period which it depicts, are unknown, but we can see that the images represent traditional, manual farming methods, with grain being flailed by hand rather than by threshing machine. The early Nineteenth Century was a period of great agricultural transformation: high-yielding crops such as wheat and barley were introduced and pasture was replaced with arable land. Agriculture became increasingly industrialised which brought about changes in rural working conditions, with only 22% of the workforce being employed in agriculture in the 1850s. The use of windmills, too, began a slow decline from the early Nineteenth Century onwards, in the wake of the development of steam power.

As for bread, because no corn had been imported during the Napoleonic Wars, Britain’s landowners had increased their wheat production and enjoyed good profits which they lobbied Parliament to protect when war ended in 1815. The Corn Laws were passed which legislated that corn could only be imported when the domestic price was 80 shillings per quarter. Bread prices had been high, especially after the terrible harvest of 1816, and the Corn Laws kept bread prices artificially high – which led to unemployment and economic decline. The laws were reformed in 1828 when a sliding scale was adopted but this was to have a negligible effect. In 1846, the Corn Laws were repealed under Robert Peel.

It seems likely that the bucolic scenes featured here hark back to a time before these changes began to take place.