The British North Greenland Expedition (BNGE) of 1952-1954 stands as a remarkable chapter in the history of polar exploration. Led by Commander James Simpson, this ambitious expedition aimed to deepen our understanding of the Greenland Ice Sheet and its surrounding environment. The archive of this expedition, housed at Newcastle University Library, offers a fascinating glimpse into the daily lives and scientific endeavours of the team who undertook groundbreaking research into the glaciology, geology and environment of this previously understudied part of the world.

The Mission and Its Objectives

The BNGE was the first large-scale British-led expedition to Greenland, involving 30 men, primarily from the military, including the Royal Navy, Royal Air Force, and Army, along with a few non-military scientists. The expedition had a broad range of scientific objectives, including geological mapping, meteorology, polar medicine, and logistics. The team established their main base at Britannia Lake and a field base at Northice, from where they conducted various scientific measurements and experiments.

Daily Life and Challenges

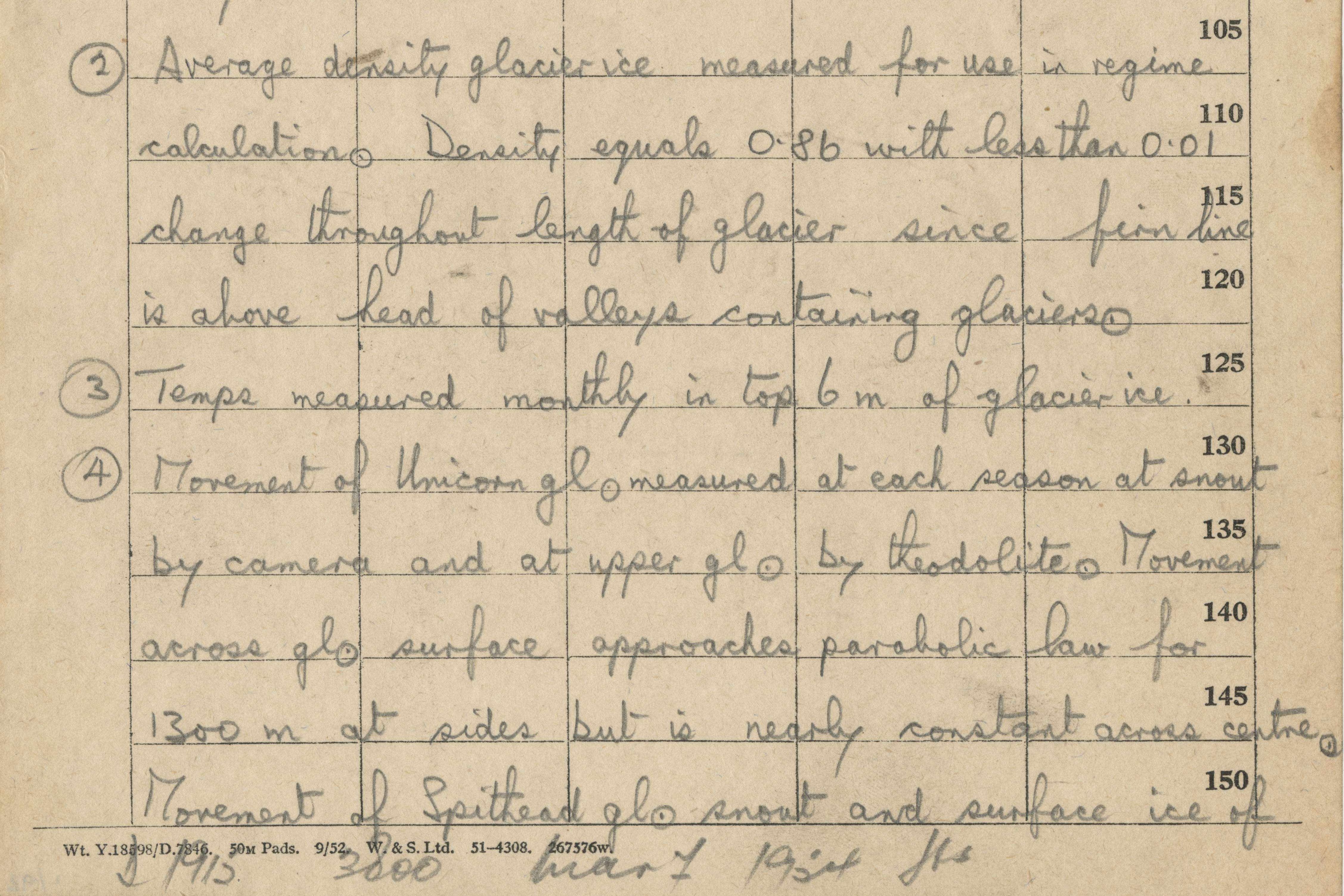

The archive contains over 700 message transcripts, detailing the day-to-day activities and challenges faced by the expedition members. These messages reveal the logistical hurdles, such as the breakdown of equipment and the need for resupply missions, often carried out by parachute drops from airplanes. One notable incident was the crash of an aircraft during an early resupply mission in September 1952, which resulted in the loss of the craft and injuries to the crew.

Scientific Contributions and Legacy

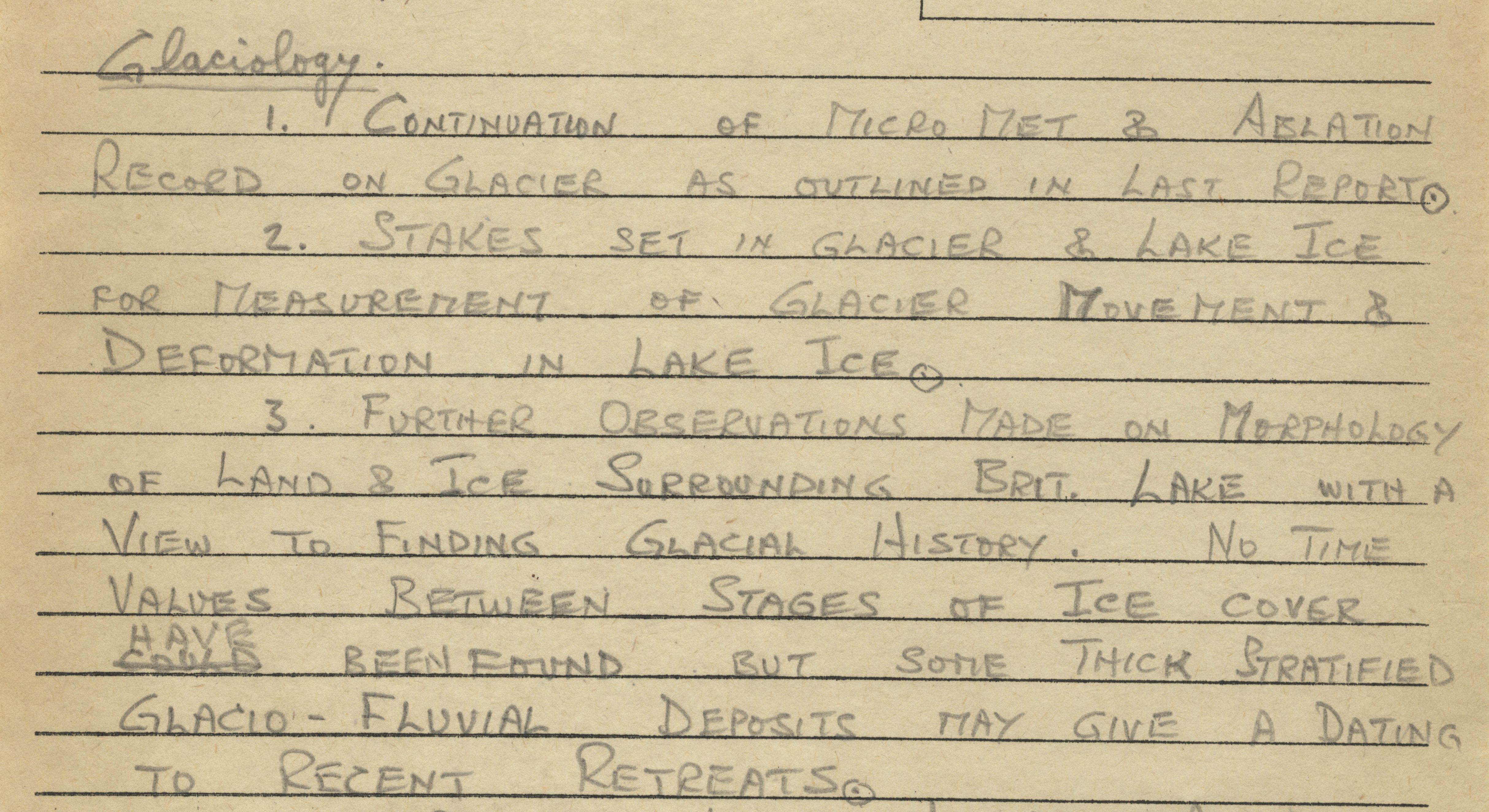

Despite the challenges, the BNGE made significant contributions to polar science. The team conducted extensive measurements of the ice sheet, gravimetry, and meteorology, using a combination of dog sleds and Weasel tracked military vehicles for transportation. The expedition also served as a test-bed for practices used in later polar expeditions, including the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1955-1958.

Notable Participants

Several members of the BNGE went on to have distinguished careers in exploration and academia. Captain Mike Banks, who later wrote a book about the expedition, and Peter John Whyllie, a geologist, are among the notable figures. Hal Lister and Stan Paterson, both glaciologists, also had successful academic careers following their participation in the expedition.

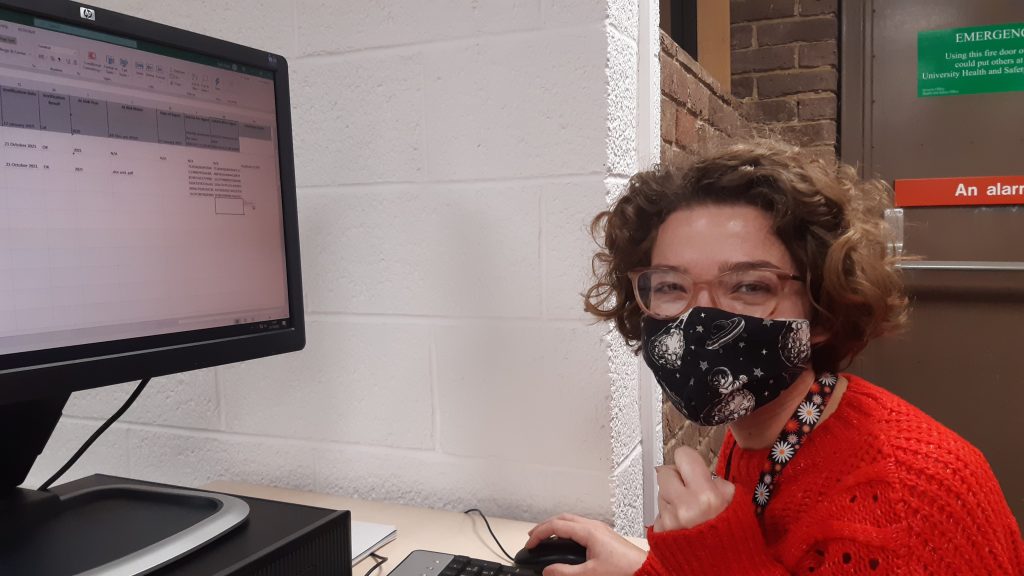

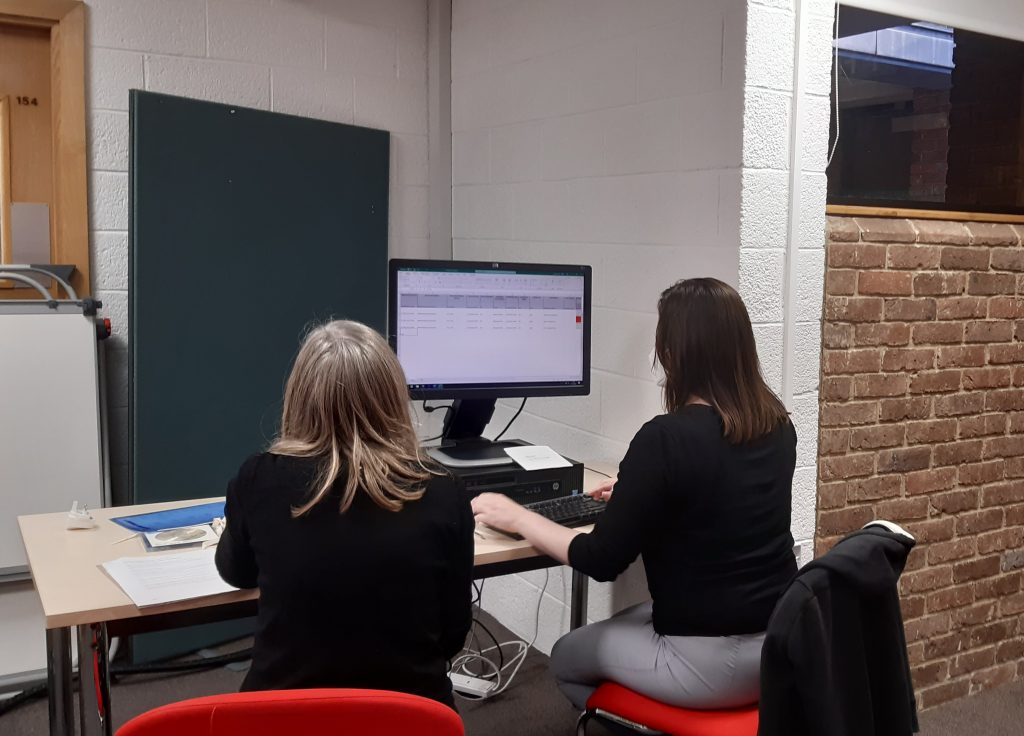

Archive and Catalogue Process

Before the archive was transferred to Special Collections it had lain in a cupboard of the University’s Geography Department for many years. Following its chance discovery in 2013, and subsequent transfer to the University Library, an award of external funding allowed the archive to be conserved, repackaged and fully digitised.

Following this, the diligent of a work of a Robinson Bequest student has allowed us to develop a catalogue of the collection and open access to researchers. This was a complex process as many of the transcripts did not contain a date and many were not in order. Therefore, an understanding of the key activities of the expedition and the day-to-day tasks detailed in the many books written by key members of the expedition was required to help the process. Each transcript was read and key details of the message senders and recipients, as well as their content was recorded. This information was then utilised to carefully place the records in the correct chronological sequence and form the basis of the comprehensive archival catalogue which is now online.

Conclusion

The British North Greenland Expedition archive is a treasure trove of historical and scientific information. It not only documents the achievements and hardships of the expedition but also provides valuable insights into the early days of polar exploration. For anyone interested in the history of exploration or the science of the polar regions, this archive is an invaluable resource can be requested through the Special Collections and Archives at Newcastle University and can be found here: https://specialcollections.ncl.ac.uk/gex

Further Reading

Read more about the history of the archive and its conservation in this 2014 blog post here: https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/speccoll/2014/03/31/cold-calling-churchill-the-british-north-greenland-expedition-1952-1954-march-2014/

Find out more about some of the stories contained in the archive in this 2023 blog post: https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/speccoll/2023/01/10/science-and-stories-from-the-british-north-greenland-expedition-1952-1954/

Find a small selection of digitised images from the archive on CollectionsCaptured here: https://cdm21051.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p21051coll156/search