On 14th June 1966 the Vatican’s list of forbidden books was officially discontinued, put in a reliquary (a container for holy relics) and covered with a glass bell. Books could still be condemned as immoral by the Catholic Church but it signified an end to being excommunicated (i.e. spiritual damnation) for reading or distributing books that offended the faith or its morals.

Johannes Gutenberg published his Bible in 1455 and this event is thought to have marked the beginning of print history in the Western world. Previously, texts were copied by hand (manuscripts) but the printing press facilitated the mass production of books. As more books were written and reproduced, and came to be more widely disseminated, the spread of subversive and heretical ideas became more difficult to control. In particular, the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648) that was initiated by the German theologian Martin Luther and continued by the French theologian Jean Calvin, generated a significant quantity of polemical works, or rhetoric that was strongly critical of Catholicism. For the purposes of preventing the corruption of ordinary Christians and helping the faithful to establish which books were immoral or which contained theological ‘errors’, the Vatican’s list, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Prohibited Books), was first published in 1559 under Pope Pius IV. It went through 20 editions, with the last being published in 1948, under Pope Pius XII.

Berkeley, G. Alciphron, or The Minute Philosopher: in seven dialogues: containing an apology for the Christian religion against those who are called free-thinkers (London: printed for J. Tonson, 1732) Bradshaw 192.3 BER.

Alciphron is a dialogue by Irish philosopher George Berkeley. This defence of Christianity found its way into the Index in 1742 and was still included in the final 1948 edition, probably due to Berkeley’s anti-Catholic views. This copy was previously owned by the radical M.P. for Newcastle, Joseph Cowen (1829-1900).

It is important to remember that this was not the only attempt to censor books at this time. European governments also sought to exercise control over printing: in England, the Stationer’s Company received a Royal Charter in 1557 and had the role of regulating the print industry. Only two universities and 21 printers operating in the City of London were licensed to print.

The Index of 1559 banned the complete works of 550 authors as well as some other individual titles. This blacklisting, particularly of work by some Protestant authors, meant that Catholics were denied access to important thinking even in non-theological subjects. Indeed, a large number of philosophers and writers that today are ‘household names’ have appeared in the Index. However, judgements about what constitutes immoral work changes and, over time, not only were new books added to the Index but some were deleted. For example, the opposition to heliocentrism (the astronomical model that places the sun at the centre of the solar system, first championed by Italian polymath Galileo Galilei) was completely dropped in 1835.

Milton, J. Paradise Lost: a poem, in twelve books, 7th ed. (London: printed for Jacob Tonson, 1705) Robinson 61.

Paradise Lost, by the English poet and civil servant John Milton, is considered by many to be the greatest epic poem in English and it continues to influence English Literature today. It was first published in 1667 but did not appear in the Index until 1758 despite it attempting to reconcile pagan with Christian tradition and depicting a tyrannical God. It was still listed in the 1948 edition of the Index. This copy was previously owned by the satirist, poet and strict Catholic, Alexander Pope (1688-1744).

Some of the major intellectual figures whose works were in the Index include: Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543); French writer Voltaire (1694-1778); Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778); Scottish empiricist David Hume (1711-1776); and French feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986).

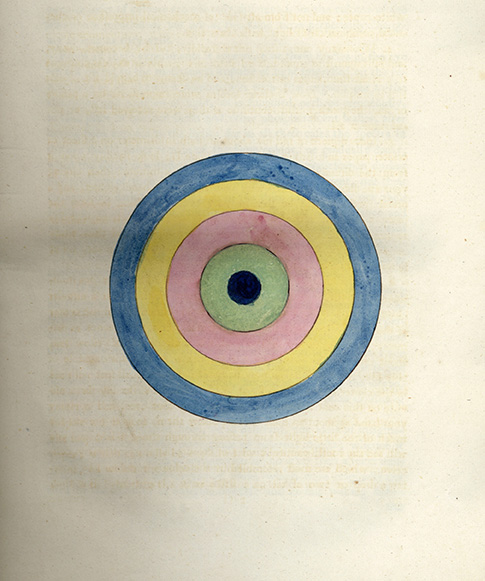

Extract from Darwin, E. Zoonomia, or, The laws of organic life (London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1794-96) Pyb.N.v.17.

Zoonomia by the British physician, Erasmus Darwin, was first published in 1794. In it, Darwin sets out laws describing animal life and catalogues diseases and their treatments. Darwin formulates one of the first formal theories of evolution (which would later be developed by his grandson, Charles Darwin). Zoonomia was banned in 1817 and remained in the final edition of the Index. Whilst people were told about the bans, the reasons why books were banned were not explained. In this instance, it is likely that Darwin’s rejection of Biblical chronology was the reason. This copy had been presented to an unidentified former owner – probably the East Kent & Canterbury Medical Library whose stamps are on the title page – by an Anglican priest called William Champneys (1807-1875) and later found its way into the library of Newcastle surgeon, Professor Frederick Pybus (1883-1975).

Darwin, E. Zoonomia, or, The laws of organic life (London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1794-96) Pyb.N.v.17.

Gibbon, E. The history of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, 2nd ed. (London: Printed for W. Strahan and T. Caddell, 1776-88) RB 824.67 GIB.

Banned in 1783, Edward Gibbon’s six-volume work on The history of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire drew heavily on primary sources, providing a model for later historians. Gibbon was accused of being a ‘paganist’, influenced by Voltaire (many of whose works were listed in the Index) and thinking that Christianity had hastened the fall of the Roman Empire.

Yet, there were some omissions that might be surprising. English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809-1882); German revolutionary socialist Karl Marx (1818-1883); German philosopher and atheist Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844-1900); English writer D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930); and Irish novelist James Joyce (1882-1941) are among those people whose work escaped the Index. Whilst the views expressed by such authors were unacceptable to the Catholic Church, their work was either considered heretical and therefore was automatically forbidden, or, did not meet the primary criteria for banning books: anticlericalism and immorality.

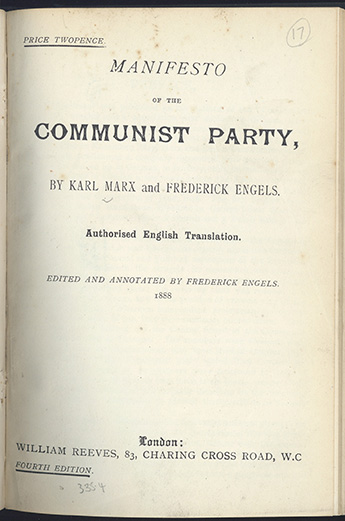

Marx, K. and Engels, F. Manifesto of the Communist Party (London: William Reeves, 1888) RB 335 SOC(17).

Originally published in London, in 1848, the Manifesto of the Communist Party takes an analytical approach to explaining class struggles and the problems of capitalism and capitalist production. It has both been praised as one of the most influential texts of the Nineteenth Century and criticised for homogenising the working classes. It has also been argued that its authors, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, were influenced by the work of John Milton, who had some works listed in the Index. Marx described religion as “the opium of the people”, giving false hope to the working class. The Manifesto was never included in the Index.