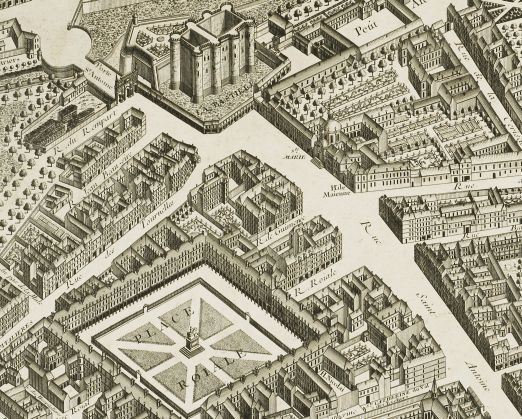

(Rare Books, RB 912.4436 BRE Elephant folio)

On 14th July 1789 the Bastille in Paris was stormed. It was a fourteenth-century fortress that had been used as a state prison from the early Fifteenth Century but would come to symbolise both despotism and the French Republican Movement.

When finance minister, Jacques Necker, was dismissed Parisians became fearful of a conservative coup. Amid widespread violence and calls for a written constitution, royal forces had withdrawn from central Paris. Revolutionaries had armed themselves on 13th July and wanted to loot the Bastille for its significant gunpowder supply. Attention had also been focussed on the Bastille by one of its infamous inmates, the Marquis de Sade, who stoked up political fervour by shouting from his cell. The commander of the Bastille, Bernard-René de Launay, tried to negotiate but an impatient crowd stormed the outer courtyard and firing broke out. By mid-afternoon mutinous royal forces had bolstered the revolutionary crowd, bringing trained infantrymen and cannons. When the drawbridge came down, de Launay was powerless. The crowd surged in and dragged de Launay to his death. The Bastille was quickly portrayed in the pro-revolutionary press as a place of despotism and terror, thus legitimising the revolutionary action that day. (Historians such as Simon Schama assert that the storming of the Bastille was the liberation of its seven inmates from a relatively comfortable imprisonment and that the prison was governed well.)

The storming of the Bastille would be the inspiration for plays and broadsides for months to come. It is widely held to have marked the beginning of the French Revolution and the end of the absolute monarchy or ancien régime (Louis XVI recognised the authority of the National Assembly on 15th July). The Marquis de la Fayette was appointed Commander in Chief of the National Guard and ordered the demolition of the Bastille – a project that was managed by Pierre-François Palloy who sold parts of the building as souvenirs.

The Bastille is shown clearly on this eighteenth-century map as a tall fortress with eight towers, adjacent to the Porte St. Antoine gateway in the eastern part of the city. Michel-Étienne Turgot commissioned a map of Paris from the sculptor, painter and specialist in perspective views, Louis Bretez in 1734. This now famous map took two years to complete and, because Bretez was permitted access to mansions and gardens in the course of his surveying and drawing, is both accurate and detailed. It comprises 20 sectional birds-eye views of Paris and its suburbs that are presented as double facing sheets. As a commodity, it was aimed at the elite: the King; members of the Royal Academy of Sciences; and wealthy foreigners. For researchers today, it is a valuable primary document, providing not only a map of Paris as it was about 55 years before the French Revolution but also drawings of buildings that have not survived.