As a researcher and activist with an interest in play streets, and in the midst of a pandemic that prevented planned fieldwork, I have spent some time in recent months piecing together some of the histories of play streets in North Tyneside, with a view to developing some academic and activist work around this theme.

As a starting point, this blog post sets out some of the developments, in time and space, of this history, from 1938 to more or less the present day. It’s very much a factual account, rather than an academic analysis, or even really an attempt to make any kind of argument.

There are lots of gaps and questions: if you have any answers, from your own experiences and memories, please do let me know in the comments below.

In 1938, parliament passed the Street Playgrounds Act, responding to concerns that many children, in poorer neighbourhoods in large urban areas in particular, were at risk playing on the streets, in the absence of any other safe and accessible spaces to play. The Hansard record of the House of Lords debate noted that “In the ten years from 1924 to 1933 inclusive, over 12,000 boys and girls under fifteen years of age were killed in the streets in England and Wales alone, and over 300,000 mutilated or injured.” In addition, this period also saw more than 2000 children prosecuted for playing on the street. In short, children’s lives were at risk as they played and they were also deemed to be ‘out of place’ whilst they played.

The 1938 act built on the experience of New York, where the Police Commissioner introduced street closures for play in 1914, and pilots in two London boroughs and in Salford and Manchester, where local schemes were introduced before the national legislation. In Salford, the local experiment reduced child road deaths to almost zero.

Local authorities around the country responded with varying enthusiasm to the new act, though by 1963, there were146 play street orders designating 750 play streets nationally.

Locally, in January 1939, Tynemouth Borough Council swiftly made their refusal to engage in this new movement clear: “No action is to be taken to close any streets to enable them to be used as playgrounds for children” whilst noting that “The council has power to do this under the Street Playgrounds Act 1938” (Evening News, 23.1.39, p.7).

When the matter was discussed at a council meeting on 25th January 1939, a Councillor Hails, referring to this recommendation, “said he was not happy about the arrangements in the borough on this question”. He argued that, in the face of the council’s refusal to designate play streets, “in certain areas of the town the school playgrounds be opened”. The mayor (Mr Harry Gee) retorted “We have nothing to do with that.” (Evening News, 25.1.39, p.1).

The first organisation in the north east to positively engage with the idea of play streets was the North East Women’s Parliament which, in February 1944, “urg[ed] upon all local authorities in the region the necessity of establishing play streets for children” (Evening News, 21.1.44, p.5), in the context of their wider work to secure space for play for children.

When this call was under review by Tynemouth Borough’s Parks and Sands Committee, the leader writer of the Evening News, “Collingwood”, expressed considerable disdain: “Surely it is not now seriously proposed that certain streets in a town should be marked off as ‘play streets’?”, he wrote, “Residents of any street specially marked off for such a purpose would, I fancy, have something to say about it.” (1.3.44, p.2). And Tynemouth Borough Council seemed to be of a similar view, stating, in April 1944, that “no action is be taken with regard to a resolution of the North East Women’s Parliament that consideration should be given to the necessity of establishing play streets for children” (Evening News, 24.4.44, p.3).

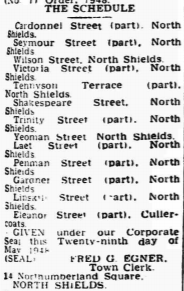

Yet, by October 1946, the Tynemouth Road Safety Committee was recommending the creation of play streets on 16 of the borough’s streets, fifteen in North Shields and one in Cullercoats (Evening News, 15.10.46, p.8):

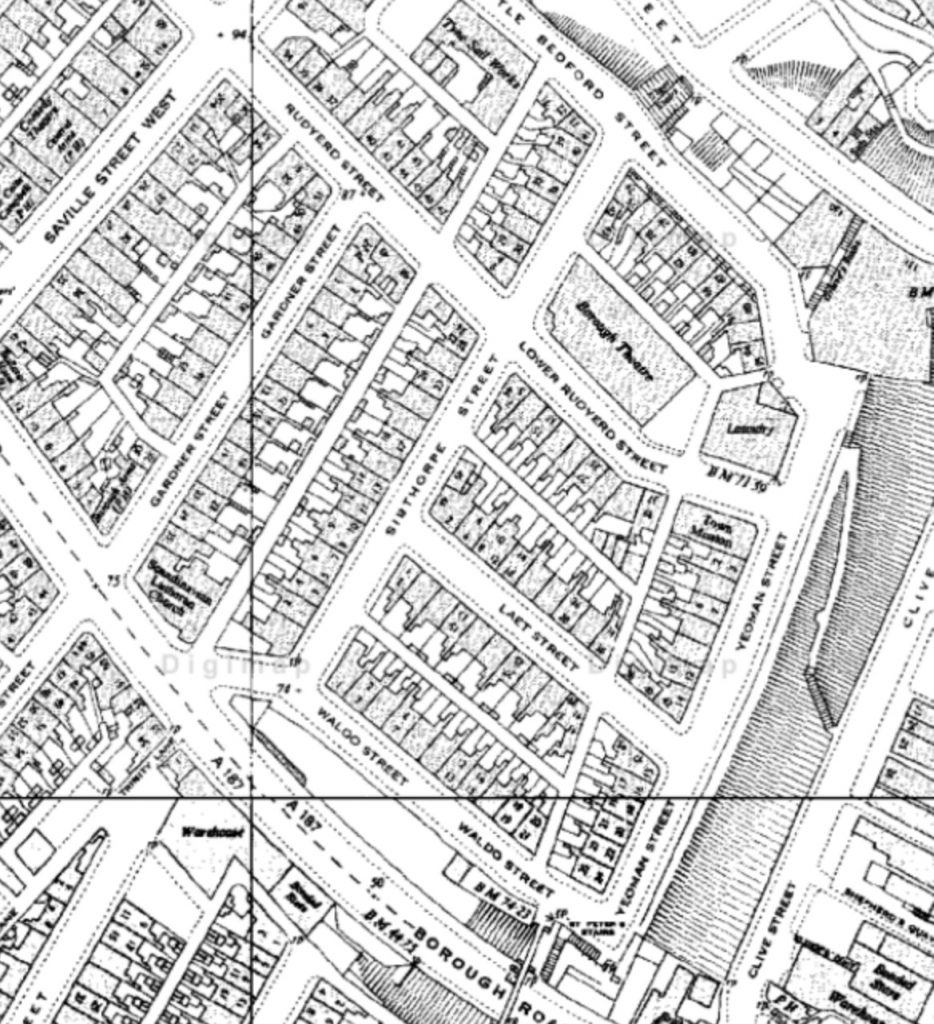

Owing to the lack of playing fields, it is proposed that the following streets be closed to vehicular traffic until such time as proper playing facilities are available for children in the near vicinity: Wilson Street, Shakespeare Street and Yeoman Street, and part of Cardonnel Street, Seymour Street, Victoria Street, Tennyson Terrace, Trinity Street, Laet Street, Thrift Street, Penman Street, Gardner Street, Coburg Street, North King Street, Linskill Street and Eleanor Street.

For reasons that were not reported, the road safety committee removed Coburg Street and North King Street from their list at their meeting on 16th October 1946. Although creating play streets on the remaining 14 streets was apparently approved, nothing seemed to happen in any hurry, prompting a concerned resident to write to the local paper asking what had happened to this “sensible proposal” (Evening News, 19.9.47, p.2). The first Tynemouth (Street Playground) Order was finally published on 29th May 1948, designating 13 streets as play streets. At some point, Gardner Street and Linskill Street were removed from this final list and never actually became play streets; this may have been because bomb damage in their immediate vicinities had radically changed the prospects for these streets. In any case, 11 streets were finally designated by this first order, 10 in North Shields and one in Cullercoats.

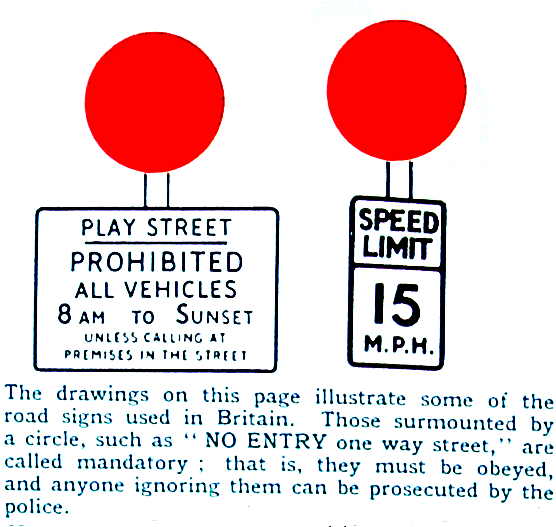

Source: Museum of London

Source: David Hembrow

This first order was very specific about the days and times that the streets were to function as play streets – Mondays to Fridays from 5pm to 9pm, Saturdays from 1pm to 9pm, and Sundays all day, from 9am to 9pm. This is quite different to the orders seen on later play street signs (see below) – at some point these times were clearly revised. And it is also interesting to note that on school days, children would not have been able to safely play out immediately after school, nor in daylight in the winter months.

Exceptions included the “conveyancing of persons, goods and merchandise”, road maintenance, and military training. The first exception in particular was significant since, in the 1950s, many of the vehicles on urban roads, especially in poorer neighbourhoods, would have been goods vehicles (milk vans, coal lorries, post vans etc.) and, as we will see, this became an issue on the designated streets. This may also explain why the streets didn’t function as play streets until after business hours on weekdays and after the likely busy period for deliveries on Saturday mornings. Even with this significant move to create safe space for children on their streets, we can still see motor vehicles and deliveries taking precedence over children, in an echo of what was to return some 60 or 70 years later when online deliveries are seen in part to account for an increasing proportion of traffic on residential streets.

Without access (in the context of the pandemic) to the borough development plan, the minutes of the Tynemouth Watch Committee, and other documents explaining the decision-making process, we can’t know for sure why these streets were chosen, but the primary aim of the 1938 Street Playgrounds Act was to create space for children to play on streets where there were high numbers of resident children and few other very local spaces for play, such that creating safer streets for play was seen as a way of bringing “relief to many mothers whose youngsters have no playground” (Evening News, 5.6.50, p.2). This seems to explain the designation of the 10 streets in North Shields, all of which were located in one of four neighbourhoods in the west of the town. The Town Clerk, Fred Egner, explained some of the rationale for the creation of play streets: “You have children playing in the streets in cases where there were no accessible playgrounds. It is the policy these days to have one or two streets where traffic is restricted, so that children can play in safety” (Evening News, 2.6.50, p.5). In this explanation, two things seem worth highlighting: the plan was indeed to have clusters of streets to create safe space in neighbourhoods, and “street playgrounds” were very much seen as a poorer alternative to playgrounds. In a theme which recurs today in debates around children’s play, it seemed the preference was that children should play in dedicated and separate spaces, rather than in the places they choose on their doorsteps. This echoes the position in Salford, where play streets had been trialled but seen as a poor substitute for “gardens and open spaces” (Manchester Evening News, 7.10.2017).

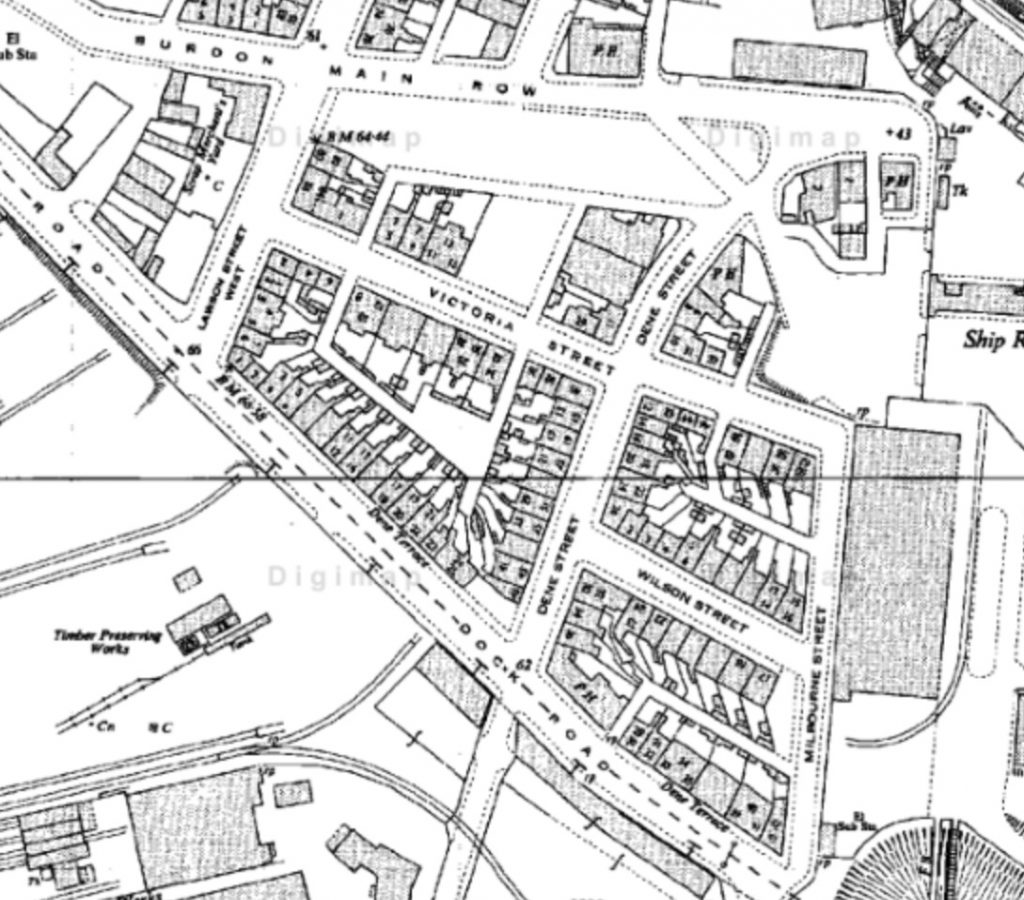

| The Triangle | Cardonnel Street, Seymour Street, Upper Penman Street; Upper Elsdon Street was also designated at a later date | ||

| Milbourne Place | Victoria Street and Wilson Street | ||

| West Ropery Banks | Shakespeare Street, Tennyson Terrace, and initially Trinity Street, swiftly replaced by Addison Street | ||

| East Ropery Banks | Laet Street and Yeoman Street |

The Triangle

Milbourne Place

East Ropery Banks

West Ropery Banks

These sets of streets were all terraces of early twentieth century housing, with many Tyneside flats, doors opening directly on to the streets. In the Triangle and East Ropery Banks, these streets remain today much as they were when they were built and in the early 1950s when they were designated as play streets. In Milbourne Place, all the homes have been demolished and whilst Victoria Street still exists, there is no trace of Wilson Street; it is visible only on historic maps. In West Ropery Banks, all but a few houses have been demolished and rebuilt, and the layout of the roads changed, though all are still traceable.

There had been considerable bomb damage in these neighbourhoods during the Second World War, with exploded bombs recorded on Addison Street and Victoria Street, and on many other adjacent streets. It’s likely that this will have been as a result of their proximity to the docks on the banks of the River Tyne and the coal mines and other industrial works to the south and west of North Shields. This would have left bombsites and vacant lots around these neighbourhoods, and it is likely, as happened elsewhere, that these sites became playgrounds for local children.

Indeed “Collingwood” in the Evening News, who had earlier been so disdainful of play streets, suggested that, in these very neighbourhoods (Evening News, 5.6.50, p.2):

some of the open spaces created by bomb and slum clearance might also be turned into miniature playgrounds for toddlers. A little fence, sandpit and a little imagination – and Tynemouth Council could, at very little expense, convert eyesores into havens of happiness for youngsters.

The demolitions and redevelopments that took place through the 1960s and 70s signal that these were all areas of significant disadvantage. This is supported by the inclusion of all these areas in the North Tyneside Community Development Project (CDP) established by the government in 1972 (till 1977) to work with local communities to organise for change in labour and housing markets, and alleviate poverty. Uniquely within the 12 CDPs across the country, play was an important part of the work in North Shields, with action groups in all these neighbourhoods identifying safe space for children to play as a key aim of their collective work, though there is no specific mention of what was happening on the designated play streets in the reports of the CDP.

The designation of play streets in North Tyneside also seemed to respond to concerns that children should not be playing out, whether it was safe or not. In June 1950, “MP” of North Shields wrote to The Evening News (7.6.50, p.2), as follows:

The first play street order was the most significant. The Evening News reported (15.10.46, p.8) that “If the closing of the streets proves successful, the provision of further play streets will be considered”. In the following years, we see both new streets designated and calls from residents, usually mothers, on other streets for play streets to be established. It seems that the designation of some play streets in the borough allowed residents elsewhere to imagine the possibility that they too might have safe streets for their children.

In almost all instances, these calls appeared in the context of deaths and serious injuries of children playing out, or of a more general concern that there was nowhere safe for children to play, and that deaths or accidents would occur if nothing was done. In some instances, these calls fell on deaf ears and highlighted the continuing battle to prioritise children’s play – and their lives – over the needs of drivers.

in 1958, the death of a six year old killed on Waterville Road on The Ridges, just around the corner from Briarwood Avenue (see below), led residents to request a zebra crossing or a play street on adjoining Rowan Avenue (Evening News, 3.10.58, p.4); mothers testifed to their fears for their children:

Every time there is a screech of brakes you are frightened to look out of the window.

It is a terrible road. Every time my children go out into the garden I am terrified in case they get on to the road.

Yet, no play street was created here.

At a similar time, on Nater Street in Whitley Bay, a local mother “pointed out there were no playing fields in the vicinity and only older children were allowed on the beach by their parents”. This would have been Whitley Bay’s first play street, but this request was eventually rejected (Evening News, 4.11.58, p.8). Similarly, a few years later, an anonymous letter from a “young mother” from Woodbine Avenue, Wallsend begged Wallsend Accident Prevention Committee to create play street, as an oasis in a neighbourhood surrounded by streets with heavy traffic. The request was passed to the appropriate council department but no play street order was ever approved (The Journal, 8.4.64, p.7). In 1979, a petition from Waterloo Place, North Shields, was rejected, after an earlier claim in 1977, on the grounds that “a Government circular suggests that play streets should not be created where the streets adjoin a busy road” (Evening Chronicle, 3.7.79, p.9).

On Lilburn Street, North Shields, in March 1968, the council’s decision not to create play street “resulted in a protest by parents” (The Journal, 29.3.68, p.9). The parents argued that:

The street is an island surrounded by main roads, and there is nowhere for our children to play unless they cross a main road. The council will probably wait until there is an accident before they do anything.

Another resident, however, objected to the proposal on the grounds that “It would reduce the value of the property with kids playing around.” This echoes concerns raised in Newcastle, in Jesmond in particular. The opposition was upheld by Alderman Thomas Crawshaw:

This is a nice wide street, and there are a lot of cars in the street which would not be able to park. We don’t think there is any need to make it into a play street.

This prioritisation of parking reveals both a concerning set of values, but also a misconception – nothing in a street playground order prevented residents from parking on their streets.

Other objections on existing play streets echoed this Lilburn Street resident’s concerns about the nuisance of children playing out. A report from Charlotte Street, Wallsend in the the Evening Chronicle (24.1.64, p.5) expressed concerns that the “big boys” from neighbouring streets had taken over the play street, marking football goals on the street, breaking windows and climbing on drainpipes to retrieve balls. At the same time, residents noted that “drivers take no notice of the warning signs and even use their horns to clear the street when they drive through it.”

Despite these concerns, objections, rejections and misconceptions, there is some evidence that the creation of play streets in the borough was shifting the prevailing view on children’s right to play on their streets. Not only were residents emboldened to demand safe space for their own children, but local organisations, such as the Tynemouth Watch Commitee, were also making more general calls for more careful driving on ‘quiet streets’. Indeed, in a remarkable shift from his position in 1944, the Evening News’ leader writer “Collingwood” was making a bold argument in support of children’s safety on their streets by 1957 (Evening News, 24.7.57, p.2).

People may argue that children should not play on streets. But they are the sort of people who have never had children of their own – who don’t realise that it is nigh on impossible to keep children safely tucked away behind a garden gate. While children may stray to danger there is no need for motorists to add to that danger. Main roads are meant to carry the traffic – not the quiet streets leading from them. Leave the quiet streets to the butcher and the baker and their vans, calling on residents. It will lead to greater safety.

It’s important to note that “Collingwood” is only asking here for a recognition that children may “stray to danger” but he was, by doing so, recognising the real danger that the growing number of motor vehicles on ‘quiet streets’ posed.

This was not the only view, however. In 1954, a “warning to parents to keep their children from playing on roads on summer nights was issued by Wallsend Accident Prevention Committee”, apparently inspired by an electricity board maintenance engineer who complained that “it was a nightmare” driving his van “because of children on the road”. The committee acknowledged the shortage of local playing fields but also noted that children were not using the local play spaces provided, and seemed reluctant to blame a spate of recent child injuries on drivers (Evening News, 8.5.54, p.4). This perspective, prioritising drivers, relieving them of any responsibility for collisions, and recommending that children play elsewhere, is echoed in a letter to the Evening News from a North Shields resident who raised concerns for those with “business clientele” in and around the play streets (specifically, Redburn View on The Ridges) arguing that the necessary diversion increased inconvenience and running costs “when the children of that area have access to a splendid play field nearby” (Evening News, 30.6.54, p.2).

Redburn View was designated a play street in December 1953 (Evening News, 24.12.53, p.10), on account, according to the Tynemouth Watch Committee, of its narrowness (Evening News, 28.10.53, p.11). Redburn View was a long street which skirted the western edge of The Ridges, passing underneath the Newcastle-Tynemouth railway line (now the metro line) and offering one of only a few crossing points on the estate. As the letter quoted above suggested, some saw it as an essential route – and this seemed to be reflected in the fact that a number of drivers were prosecuted for driving down this street (see below).

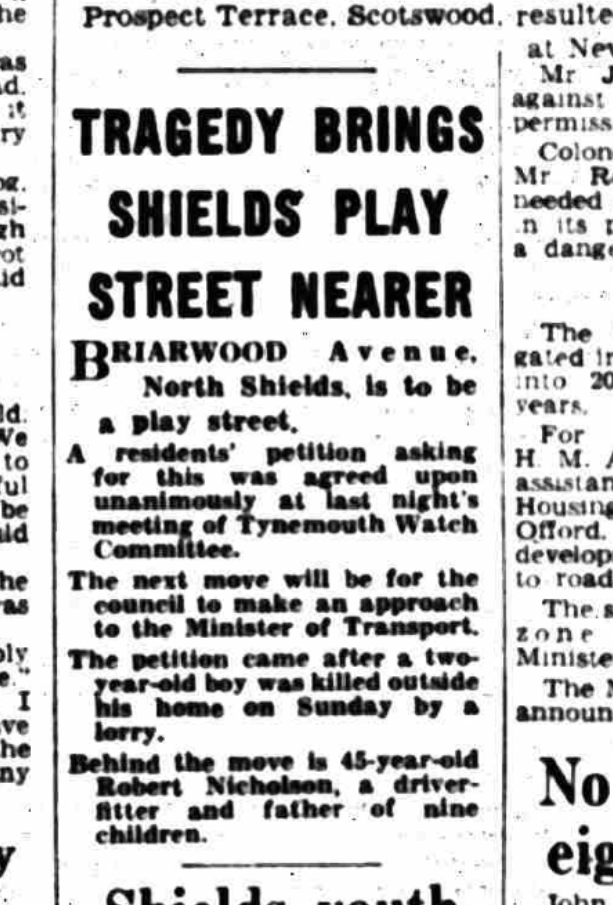

As far as I can tell, the only successful resident petition for a play street designation came from an actual, rather than feared, incident. On Briarwood Avenue on The Ridges, the death of a two year old boy, killed by a lorry driver outside his home, led to a unanimous residents’ petition, led by a father of nine, to Tynemouth Watch Committee (The Journal, 5.10.60, p.3). Briarwood Avenue was designated a play street around late 1960.

Briarwood Avenue today (now Kingsbridge Close and Amble Close)

In 1959, a successful request came not from residents but from an organisation, the Poor Children’s Home Association, a forerunner of Children North East. The PCHA opened a children’s home, Eustace Percy House, at 36 Beverley Terrace, Cullercoats, and campaigned for a zebra crossing from the moment they opened, so that their resident children might safely access the beach across the road for play. The request for a zebra crossing was rejected and “the children [were] told to use the back lane” for play (The Evening News, 7.1.59, p.6). In February 1959, a play street order was approved for Back Beverley Terrace, from sunrise to sunset.

The only other clearly documented designations came in May 1963, from Wallsend Council. At the time, the town council seemed to be investing in new play spaces, creating both new playgrounds and new playing fields, often around new housing developments. In this context, residents of Myrtle Grove, Wallsend – a street of early twentieth century terraces and Tyneside flats – requested a play street. The response was surprising: “the council is going one better. It is to seek approval to make not only Myrtle Grove, but its neighbours Ash Grove and Willow Grove, into play streets.” (Evening Chronicle, 9.5.63, p.13). This was the only other occasion when a set of neighbouring streets was designated, as they had been in the first order in North Shields.

The southern half of Collingwood View, North Shields, was designated in early 1960 at the request of the Tynemouth Watch Committee, reported in an article entitled “This street is for children” (Evening Chronicle, 4.2.60, p.18). Charlotte Street was designated in October 1962. Others streets designated included Rae Avenue, Douglas Street in Wallsend and The Nook in North Shields. I don’t yet know much about these streets’ designation – any information would be most welcome.

It seems Whitby Street in North Shields was also at some point designated as a play street. Its neighbouring streets, Coburg Street and North King Street, were both listed in the first set of streets identified by Tynemouth council, but not in fact designated. I can find no trace of Whitby Street becoming a play street and it is not currently covered by a play street order, as far as I can tell, yet past residents recall it being a play street, and indeed in 2014 (and earlier) the sign is clearly visible on Google Street View. There is, however, no sign today.

Some of the confusion around the timing and purpose of designation comes from the restructuring of the local authorities in the area in the 1970s. North Tyneside Council was formed in 1974, out of an amalgamation of Tynemouth Borough Council and Wallsend Council, together with parts of Whitley Bay, Longbenton and Seaton Valley, all previously in Northumberland. While some play street orders were formally published on the pages on the Shields Evening News, others were reported Newcastle’s Journal or Evening Chronicle.

As far as I can tell from reports in local papers, the reception of all these play streets was mixed. In September 1951, just a few months after the first order, “Collingwood”, now a vocal supporter of play streets, raised concerns about motorists ignoring the signs, such that some of these streets were “carrying as much traffic as ever” (Evening News, 28.9.51, p.2). “Collingwood” quoted a driver saying “it was about time some of them showed a bit more responsibility and recognised the children’s right to play in the streets”.

Some motorists’ reluctance to abide by the new orders resulted in prosecutions, documented in the pages of the Evening News. In July 1955, George Wells of Newcastle was fined £2 for driving down Redburn View (Evening News, 27.7.55, p.2). In June 1956, Stanley Rees Evans of Monkseaton was fined 10 shillings for driving down Addison Street “without stopping” which he described as “a genuine mistake on his part” (Evening News, 11.6.56, page unclear). In April 1958, Elsie Rollo was fined £1 for “driving in a street playground” [Penman Street], while on business for her employer; her defence was that “I did not notice the sign as that district was new to me” (Evening News, 16.4.58, p.5). In September 1958, a driver, Raymond Oliver, from one play street (Eleanor Street) was fined £1 for driving his van down another, Redburn View (Evening News, 15.9.58, p.7) and another driver, Robert Clark, was fined £2 for driving down the same street. For an offence in the same month and on the same street, a 16 year old was also prosecuted and fined 2 shillings for riding a motorcycle (Evening News, 18.9.58, p.8).

Cyclists too, perhaps surprisingly, were also prosecuted for contravening the play streets orders. In June 1953, four men and two juveniles (both boys aged 16) were discharged by Tynemouth Magistrates’ Court, with costs of 4 shillings each for riding bicycles down Addison Street on May 27th of that year. It seems the Chief Constable wanted to make an example of these cyclists as it was reported that “the prosecutions had been brought to publicise the fact that no vehicular traffic is allowed to pass through a play street during the day” (Evening News, 18.6.53, p.7; see also Evening News, 17.6.53, p.6; Evening News, 19.6.53, p.2).

There are certainly questions to be asked here about why it was cyclists, two of them aged just 16, who were held up as an example to drivers, but this seems to reflect real issues with motor vehicles continuing to use Addison Street regardless of the play street order. In March 1953, there were regular reports of heavy lorries cutting through Addison Street from the docks to the town centre – precisely the kind of traffic the play street orders were intended to prevent – and this left mothers fearful for their children, who often played on and around the street’s bombsite (Evening Chronicle, 13.3.53, p.22).

Many of these reports also seem to suggest that the times of the orders had been revised by this point, to reflect something like the current orders which are generally 8am, or sunrise, to sunset.

These contraventions – by drivers, perhaps, rather than cyclists – resulted not surprisingly in injuries and deaths on the designated play streets. It is clear that a play street order did not guarantee the safety of the children at play.

In September 1953, a 20-month old boy, David Marsh, who lived on Wilson Street, was found by a 6 year old neighbour with a crushed shoe and a broken leg: “it was thought that a heavy vehicle might have passed without the driver’s knowledge” (Evening News, 4.9.53, p.8).

Even after the earlier recorded child death led to the creation of a play street on Briarwood Avenue, three year old Ellen Teague was knocked down by the driver of a coal lorry in November 1961, less than a year later (The Journal, 3.11.61, 3).

Real concerns were raised on Rae Avenue in Wallsend, as this letter published in May 1970 (6.5.70) shows:

Rae Avenue today

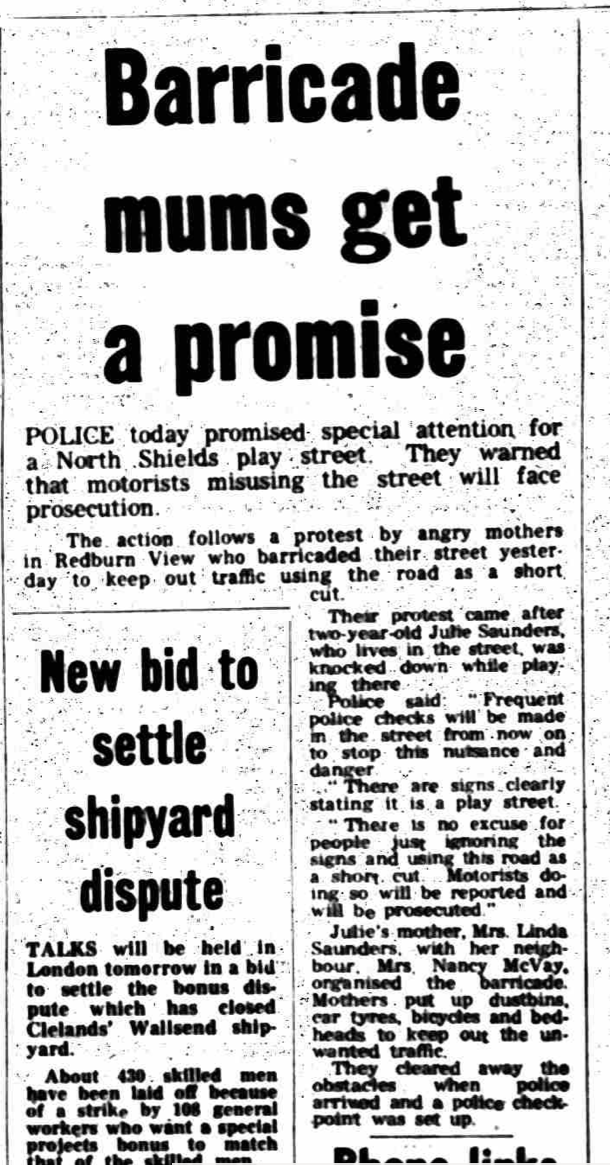

On Redburn View, five children were knocked over by drivers in eleven months in 1972; one incident resulted in a four year old being hospitalised with a broken leg and a fractured skull. These continuing dangers were the result, residents argued, of drivers driving straight through their street and a failure of the local police to enforce the play street order. The mothers on the street embarked on a campaign in August 1972 to demand better policing of the play street order. They established barricades of “dustbins, car tyres, bicycles and bedheads” (Evening Chronicle, 16.8.72, p.5) to stop drivers cutting through and successfully forced the police to set up a checkpoint on the street:

Police have promised special attention and checks … and prosecution for motorists who misuse the street … But the mothers warned that the barricades would be back if police checks were shortlived.

This attentive policing was indeed shortlived – by 1973, the mothers were protesting again and wanted a permanent solution. The play street wasn’t working:

In a play street, you should be able to let your children play out safely and not have to worry. But you can’t leave them alone for a minute, it’s just like a main road.

The mothers wanted bollards in the middle of the street to prevent through traffic (The Journal, 16.7.73, p.9). They didn’t get them and, in 1976, a six year old girl, Sharon Parkinson, was “flung into the air” and killed by a driver on the street, by this point renamed Banbury Way. The driver admitted driving under the influence of alcohol and was fined £30 and banned for driving for 12 months (The Journal, 7.10.76, p.3).

At some point after this, Banbury Way was turned into a no-through road, as part, I think, of the redevelopment of The Ridges (or Meadowell, as it was by then known), but it seems that by this point the play street was almost entirely non-functioning, despite its continuing designation. (If you know any more about this change, please do let me know).

I have not found any prosecutions for play street contraventions after 1958 and I think the last of the designations were in the 1960s. It is also clear that there were growing struggles to enforce the existing orders by the 1970s, as the Redburn View protests suggest.

The experience of Tyne Street in North Shields in the 1970s perhaps points to a change of policy with regard to play streets in the borough. In September 1972, a 3 year old child was knocked down and killed on the street. Residents were concerned that drivers were distracted by the river view – the street runs parallel to and overlooks the Tyne – and pulled together a 221-name petition for the street to be designated as a play street (The Journal, 9.9.72, 7). Their petition was unsuccessful: “The mothers … heard that the play street had been rejected because the signposting was too expensive”; “We will do our own sign boards … Give us the go-ahead and we will have them up in 24 hours”, a Mrs Darroll responded. In November 1972, the council, now North Tyneside Metropolitan Borough Council, suggested “closing the street as a link road and making it into a series of cul de sacs, with amenity areas in between” (Evening Chronicle, 3.11.72, p.11). The plan was to introduce temporary bollards for an experimental period, closing the street to all but access, with a view to investigating the long-term feasibility of the proposal.

A similar story from Whitley Bay in 1971 reinforces the idea that there was a move away from designating play streets towards closing roads to through traffic more generally. In August of that year, a group of mothers in Ventnor Gardens, Whitley Bay, barricaded their street, with dustbins and placards, to create a safe space for their children to play. The mothers complained that day trippers parking on and driving up and down their street were making it dangerous for their children; a six year old boy had been knocked down recently. Unlike demands, for example, on Lilburn Street just three years earlier, there is no mention of a desire to establish a play street; instead the mothers wanted their road closed to through traffic altogether. Councillor Freda Rosner, who supported the mothers, was reported as saying “This is ridiculous. We have become slaves to cars.” (The Journal, 9.8.71, p.7).

It is not clear what happened to the plans on Tyne Street nor the demands on Ventnor Gardens. As far as I can tell no changes were made on either street, at least not permanently. But it also seems like these accounts reflected a popular and policy switch from play streets to the introduction of other kinds of road closures, including modal filters – bollards or other barriers that restrict motor vehicle access but allow those walking and cycling to pass – on residential streets. A number of the other designated play streets, such as Briarwood Avenue (now Kingsbridge Close and Amble Close), The Nook and Collingwood View, now have modal filters, of unclear origin and timing.

In North Shields, it seems that creating and managing safe space for play was increasingly tied up in its redevelopment, within and beyond the Community Development Project. The redesign and redevelopment of streets on The Ridges and in the town centre neighbourhoods seemed to open new questions about the place of play in residential areas. In 1974, adventure playgrounds were created in Meadowell (as The Ridges were renamed in 1968) and in East Howdon (the former intended to be a permanent site and the latter temporary) and, as I’ve suggested, campaigns for better play facilities, including playgrounds and play schemes, were a key part of the CDP work. In The Triangle, a later attempt at redevelopment through the creation of a so-called Home Zone in the early 2000s also forefronted the creation of safe street space, for play and for community life more generally; indeed, home zones were seen by some to “offer[..] a renewed commitment to the concept” of the play street.

In this preliminary review of North Tyneside’s play streets we can highlight a number of themes and questions.

- Tynemouth Borough Council embraced the idea of play streets when many other local authorities didn’t, including others in the north-east; there was clearly a policy decision in the late 1940s that enabled this.

- Play streets were seen as an alternative in the absence of accessible playgrounds, and playgrounds were seen as by far the better option.

- The designation of play streets did seem to open up a more public debate about the place of play on residential streets and dangers posed by rising vehicle ownership.

- Almost all the streets designated were in North Shields and seemed to be connected to alleviating housing and environmental disadvantage.

- Wallsend Town Council embraced the idea of play streets later, but seemed to see their value as part of their play provision.

- Enforcement and prosecution dropped off extremely fast such that by the 1960s, or perhaps 1970s, these streets barely functioned as play streets.

- Mothers played an important and visible role in demanding and sustaining play streets and ensuring that the real dangers posed to children by drivers on residential streets remained on the agenda.

- Play streets did not protect children from injury and death on North Tyneside’s streets.

Twenty-one North Tyneside streets, most identified here, remain designated as play streets to this day, with orders covering either 8am or sunrise to sunset; this includes streets which no longer exist and ones which have been renamed in successive redevelopments. On many of the streets, the signs are still up but there are few indications on any of these streets of children playing out today. (For more images from a tour I did of these play streets, check out this Twitter thread.)

Douglas Street

Laet Street

Myrtle Grove

Penman Street

The Nook

Willow Grove

Residents on Cullercoats’ Beverley Terrace have recently launched a campaign to revitalise and enforce their dormant back lane play street, raising the question of the potential for others to be reviewed. On Charlotte Street, Wallsend, the council has just begun work on the renovation of eleven neglected properties, with a view to “deliver an improved physical environment, clear community benefits and increased stability”; this perhaps offers an opportunity for the street’s play street order to be revived and for play once again to be part of the borough’s framework for community redevelopment.

There is much more to be gained from reflecting in depth and detail on the history of North Tyneside’s play streets, a bold and important experiment in the life of some of the borough’s streets. There are many resonances with contemporary debates about car dependence and the regulation of traffic, the everyday life of our streets and neighbourhoods, and the place of children and their play in public space.

For now, if you have stories, memories or reflections to add, please do let me know in the comments.

My thanks to Sally Watson for sharing some of these stories – and a fascination with play streets – with me.

Thanks for an interesting piece of research and blog. I grew up on the Ridges/Meadow Well estate in the 1960s-70s, and well remember playing in the street; though there were alternatives, especially given fences had been taken down so that no one had their own garden any more. Your blog was all the more satisfying to read in that it reflected tensions between groups on the Meadow Well estate — even if as broad as mothers vs. drivers. That’s one better than most studies I’ve seen, which don’t reflect the exclusion of non-white residents from involvement in community improvement efforts,

Thanks for your comments, Karen. I know that the history of the Ridges/Meadow Well is quite contentious. Do you have memories of the adventure playground from the 1970s?

My mum lived on Peartree Crescent as a child which I believe was on the Ridges. She was born in 1944. She says she played out constantly but remembers few cars or vans. Her memories are of horse and carts still being used. My dad lived in a cottage a Billy Mill (born 1940) and he too remembers the horse and cart still being used for most things – he says cars were a novelty seen about once a week.

Hi. We are doing some historical research on Yeoman Street (formerly East Ropery Banks) Can I presume from your excellent article that, in theory, Yeoman Street and Laet Street are still playstreets? As such no traffic is allowed between 8am and sunset, with certain exceptions? Maurice

Hi Maurice. Thanks for your comment – I’m intrigued by your research. Yes, Laet Street and Yeoman Street are still, legally play streets, actually “from sunrise to sunset”, and with a big ‘except for access’ clause – so it’s effectively through traffic that is barred. I submitted an FOI to the council earlier in the year because I thought the traffic orders were all still in place, and the FOI confirmed that they are. If you’re thinking about acting on this information in some way, I’d be very keen to stay updated. A few historic play streets are looking again at their status. Alison

Hello Alison – I’m trying to find out where the “rec” in Whitley Bay would have been in the 60s and early 70s. Do you or any one reading this have any idea? Not the Please note I’m not looking for the Rex- the “rec” was a field, apparently.

Hi Patricia. I don’t know, I’m afraid. Have you tried asking on any of the local history/nostalgia Facebook pages? People there always seem to have answers. I’ve had a quick look on a 1950s map and can see lots of football pitches (especially around Marden Quarry). The Churchill Playing Fields were also there then. I hope you manage to find the answer!