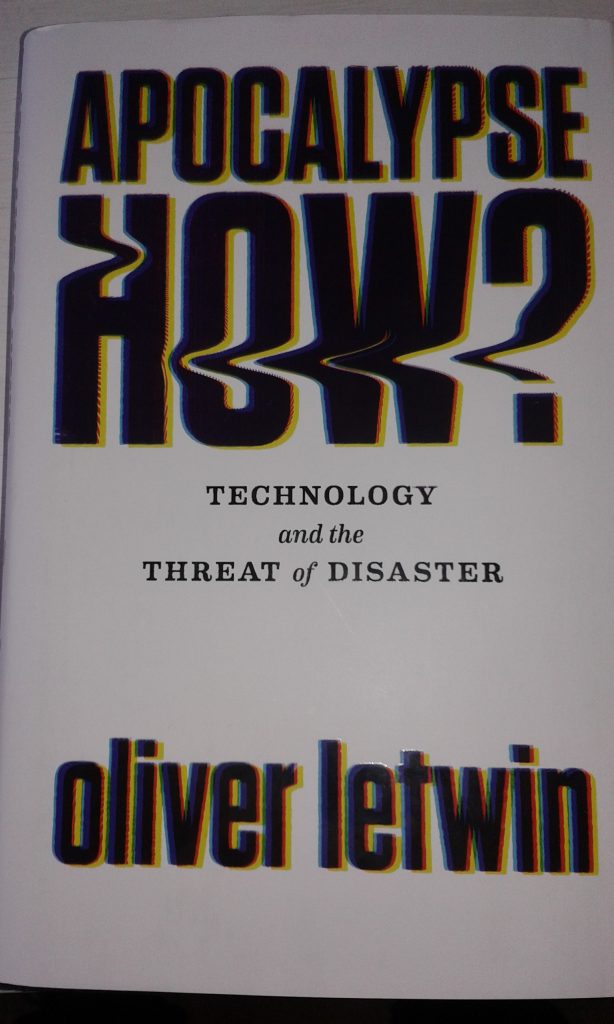

Oliver Letwin (2020) Apocalypse How? Technology and the Threat of Disaster, London: Atlantic Books, ISBN 978 1 78649 686 7, £14.99.

The UK, and world, is in crisis due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments have seemed slow to respond. Under these circumstances it is instructive to note that one former UK government minister, Oliver Letwin, has just published a book on disaster management positing a catastrophic technological breakdown. Here I review Letwin’s book, both on its own terms, and through the prism of the current crisis.

Letwin’s book is based on his experiences as Cabinet Office minister between 2010 and 2016. During this period he was Minister for Government Policy, from 2014 Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, a member of the UK’s National Security Council, and crucially for this book, UK minister for national resilience, which included cyber resilience.

The disaster he foresees is one of a catastrophic electricity grid failure which takes out all internet-based networks and communication. Setting the scenario a little into the future, he posits a situation where effectively every means of communication, transport, commerce, is reliant on internet-based technology. Think of the internet of things (IOT) currently increasingly populating households, the proposed widespread uptake of electric cars and transport, and reliance on satellites for location and communications all going dead to begin to see the profound implications.

Back-up forms of communication have been discontinued because of cost, the feeling that the networks are robust and well defended, and that there was therefore no significant probability of such a failure. Such a premise has also been deployed in fiction. One of Henning Mankell’s Wallander novels, Firewall, was also premised on such a failure. The potential problem has only grown with greater, and potentially more disastrous, effects since then.

The book intersperses fictional chapters, with more analytical discussions every second chapter. The fictional chapters are seen partly through the eyes of Dr. Bill Donoghue, Duty Officer at the Bank of England when the failure happens, and the personal and professional issues it raises for him. These chapters include convincing descriptions of how the inevitable COBR meetings unfold and the unenviable choices facing participants. In the end, the outage lasts five days and leaves many thousands of people, often vulnerable and elderly, dead.

Analytical chapters discuss how low probability ‘black swan’ events, such as the grid and network failure premised in the book, are often discounted by policy makers, and what might be done to avoid that. The answer is to build in resilience by scenario-planning which provide layers of fall-back options. In relation to grid and network failure, this means having available old-style fail-safe analogue communications, such as walkie talkies and analogue phone lines, and non-electronic details of critical infrastructure. Letwin goes so far as to imagine how the threat of such catastrophic technological failure might be mitigated at the international level. He posits a long diplomatic march which ultimately helps get momentum behind the idea of a UN-based Convention on Global Network Protection.

Letwin’s book is a welcome reminder about the potential fragility of the connected world that we live in. It is recommended reading for anyone interested in public policy around technology, disaster management and interconnectedness more generally. Given current events around COVID-19, it is however difficult not to read it through the lens of the current government response to the unfolding public health crisis. While clearly a different type of crisis, there are some lessons in Letwin’s book that help interpret current events.

The first, and perhaps most important, is that in dealing with such a crisis it is important that decision-makers have what he calls ‘emotional intelligence’. What he means is that while technical expertise and skill will likely be available to those in charge, such emotional intelligence will help them ask the correct questions of these experts to begin with, so that correct decisions can ultimately be made. In other words, the buck stops at the top with leaders who need to be both sympathetic to the problems being experienced by individual citizens, society, the economy and so on, and have sufficient analytical capacity to ask the right questions and balance the consequences to begin with.

The second is that there are what Letwin calls ‘hidden public services’. These include the food supply chain and pharmacies. Since they are in the private sector, these are not always recognised. Letwin also includes in this category having sufficient transport capacity – airlines etc – to repatriate people who may be stranded abroad during a crisis.

Thirdly, Letwin discusses the tendency to bring in ‘free-thinkers’ to ‘think the unthinkable’ and prevent groupthink among experts. As he puts it (p.82) ‘such efforts often fail , because those who are engaged to think the unthinkable genuinely do just that – and end up being discounted by the experts as eccentric – or seek to preserve their standing with the experts by engaging in self-censorship in order to raise only those thoughts that the experts consider to be at least nearly thinkable’.

The final lesson is not explicitly drawn out, but is evident throughout. It is one of complexity, of how one crisis or disaster can lead to multiple sub-crises in different fields or levels. Thus, in the book, the power and network outage leads, among other things, to the inability of emergency crews to communicate, the filling up of hospitals and the inability of councils to locate vulnerable people they have responsibility for because these details are all stored on computers and cloud computing services.

These issues all have resonance in the current COVID-19 crisis. The world has looked at the UK response with alarm. It is far from clear that the UK government, Prime Minister Boris Johnson, and key ministers were engaged enough with the outbreak early enough. It is equally far from clear that they were prepared to ask the correct questions of experts, and not place too much faith in advisers such as Dominic Cummings who like to give the impression of ‘thinking the unthinkable’. ‘Emotional intelligence’ has appeared lacking, to put it mildly.

Only after widespread reports of supermarket shortages circulated did the government seem to appreciate the ongoing difficulty faced by food suppliers, and how other private enterprises might contribute to public cohesion. And this is clearly a complex individual, social and economic crisis playing out at several levels. To take one example, which will grow in resonance the deeper into the crisis we get, many councils are understandably restricting household waste collections. Already cut to the bone, such services are nonetheless also vital for public health and have the potential to lead to an unforeseen secondary crisis. Similarly to Letwin’s account, this is also a crisis hitting the health service and the elderly in complex ways.

Finally, to return to technology, with a huge increase in working from home, networks have shown signs of at least creaking, while vaunted online services – online shopping, Netflix and so on – are struggling to cope with the demand or restricting quality. Were networks to crash, as Letwin warns, this would amplify the current problems by many multiples.

Letwin has therefore written a thoughtful and timely book. A Conservative MP from 1997, he stood down at the 2019 general election having had the whip withdrawn by the Johnson government over his attempts to find compromises over Brexit. It is to be hoped that someone of Letwin’s experience is helping guide resilience and co-ordination during the current crisis. Yet incredibly, at the time of writing, no minister is cited as having been given the role, and previous incumbents up to 2019 seem to have resilience mentioned only hand in hand with cyber problems. Since Letwin, none have been particularly senior. If so, and given the multitude of potential and current threats to national security, this at minimum surely needs rethought as the UK goes forward.

Alistair Clark

26th March 2020