Posted by Andy Pike, 17th February 2015

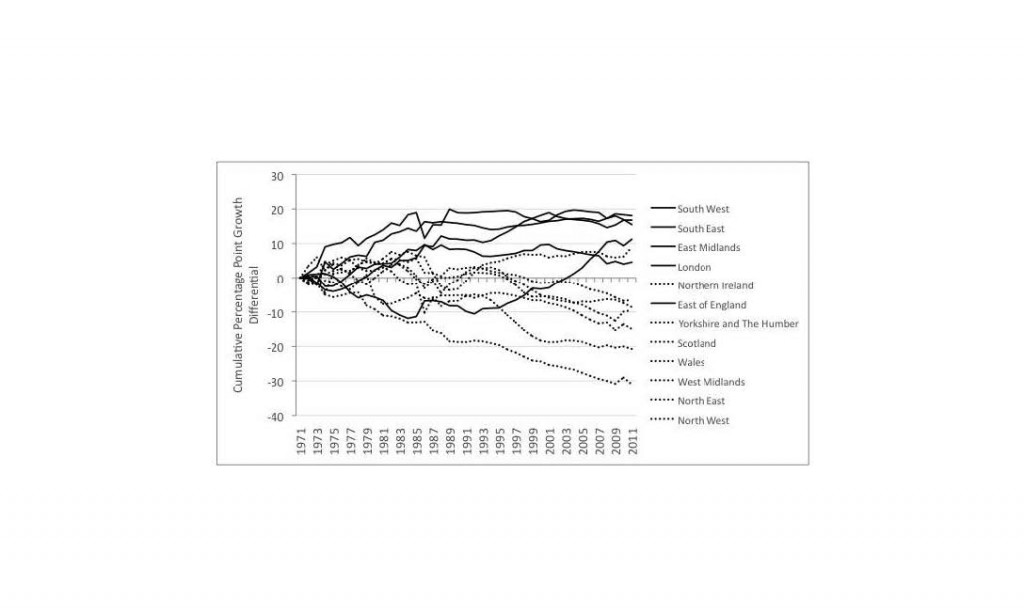

Spatial disparities in economic and social conditions have been an entrenched and persistent feature of the UK landscape since the middle of the 19th century. The scale of spatial disparities has grown since the late 1970s, accelerating during the 1980s, and continuing to increase during the 1990s and 2000s (Figure 1). Spatial disparities in the UK have far outstripped those in France, Spain, Italy, Germany and (at state level) the US. In the post-war period, the UK pioneered regional policy to address spatial disparities based on economic, social and political arguments for more balanced development that promoted wider economic opportunity and better mobilised the assets, resources and skills of people and places across the nation.

Figure 1: Regional Cumulative Percentage Point Differential Growth Gaps of GVA (2005 prices), 1971-2011

Source: Cambridge Econometrics

In the wake of the global financial crisis and ‘Great Recession’, spatial disparities and the geographical concentration of economic activities in London and the Greater South East formed part of the diagnosis of the UK’s ‘unbalanced’ growth model that was over-reliant upon (financial) services, the public sector and high levels of corporate and consumer debt and imports. The UK Coalition government has made a commitment to ‘rebalancing’. In the context of austerity, this ‘rebalancing’ has been characterised by deficit reduction, fiscal stress, public expenditure and employment reductions, growth and recovery-oriented development policy, a private sector focus, particular forms of decentralisation and state shrinkage and hollowing-out.

In England, territorial development, institutions and policy for ‘rebalancing’ have focused upon two not always integrated agendas that have aimed to shift power to local communities and business, enable places to tailor approaches to local circumstances, provide incentives for growth, and support investment in places and people to tackle barriers to growth. First, following the dismantling of the regional tier of Government Offices, RDAs and Regional Chambers, the Local Growth agenda aimed at ‘realising every place’s potential’ assisted by decentralisation and localism. A new institutional framework of 39 Local Enterprise Partnerships was established led by the private sector, working on functional economic areas and each with wide variations in economic performance, potential and resources. At reduced funding levels, new policy instruments were set up including the Regional Growth Fund, Growing Places Fund and Single Local Growth Fund alongside EU funds where eligible.

Second, the Cities agenda has focused upon cities and city-regions as the engines of economic growth, prosperity and ‘rebalancing’ as economic counterweights outside London. Several waves of City Deals with 29 (and counting…) city-regional groupings in England and Scotland have been rolled-out involving bespoke agreements between central and local government aimed at supporting growth and job creation using public and private investment, identifying national government measures to support delivery of the plans, securing greater local control over public spending, the pooling of resources across functioning economic areas, and the planning and delivery of strategic local infrastructure investment.

In the context of a further decentralising UK, what does the experience of rebalancing, territorial development, institutions and policy in England since 2010 mean for Wales? There are a few things to highlight. First, the conundrum of the governance of territorial development in England has become more acute in an asymmetrical and decentralising UK. This issue has been given further momentum following the Scottish independence referendum result and is being focused upon potential fiscal devolution to Combined Authorities and Metro Mayors at the city-regional scale. Where such developments leave further decentralisation to Wales will warrant thinking through and reflection especially given the city-regional focus to developments in England.

Second, the period of churn, instability and uncertainty since 2010 is but the latest episode in what Geoff Mulgan has called the “perpetual restructuring” of the British state. This compulsive reorganisation has generated endemic institutional churn, disruption and fragmentation for (non-statutory) economic development. The period since 2010 is another swing of the pendulum in the post-war history between the regional (early 1960s), local (c. 1979-1994), regional (1997-2010) and local (2010-) levels. England’s experience is a long way from the continuity, stability and long term strategic planning for territorial development evident internationally and provides a cautionary lesson for Wales in reflecting upon its aims for new strategies and institutional reform.

Third, structural problems remain unresolved in the new territorial development and policy landscape in England between centralism and localism, competition and collaboration, agility and “bureaucratisation”, and limited and uneven capacity and resources. ‘Deal-making’ has become the preferred method of centre-local relations with highly uneven outcomes in terms of powers and resources amongst the ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. While no easy answers exist to address such issues, thinking them through up front and in advance of strategy making and reform is worthwhile. ‘Deal-making’ as a framework for public policymaking especially needs further scrutiny.

Last, the new context has meant reduced resources, fragmentation, weakened strategic leadership over larger geographies, increased centralisation and highly constrained decentralisation leading to drift, lost momentum, diluted expertise, reduced confidence and debateable impacts on local growth and prosperity. Such problems in England provide food for thought in formulating territorial development policies in Wales in the current context.

The frustration with the patchy and slow progress of reforms in addressing ‘rebalancing’ has stimulated ideas – being developed as part of a policy intervention with the Regional Studies Association – to inject some fresh life into the case for a more balanced approach to spatial economic growth and development policy in the UK. Some of these may resonate with potential measures in Wales and include: i) aligning and matching the economic and spatial strategies in the devolved territories with one for England; ii) integrating industrial and spatial strategy and policy; iii) establishing Territorial Investment Banks beyond the City of London; iv) providing better territorial co-ordination of public investment flows; v) bolstering the role of anchor institutions such as large employers in the private and public sectors especially universities; vi) using public procurement and the dispersal of public sector activities and assets to stimulate industrial and territorial development; vii) formulating a ‘road map’ for further decentralisation of governance across the UK; and, viii) for England, strengthening and consolidating the LEPs.

Andy Pike contributed an invited presentation and chapter on ‘spatial disparities, ‘rebalancing’ and territorial development policy to the Wales TUC debate and publication on industrial policy in Wales in Cardiff on Tues 20 January 2015. The contribution is part of an edited collection published by the Wales TUC.

[1] Gardiner, B., Martin, R., Pike, A. and Tyler,

P. (2014) The Case for a More Spatially Balanced Approach to Spatial

Economic Growth and Development Policy in the United Kingdom, Policy

Intervention with the Regional Studies Association, http://www.ncl.ac.uk/curds/news/item/curds-contributes-to-the-case-for-a-more-balanced-approach-to-spatial-economic-growth-and-development-policy-in-the-uk