Posted by Andy Pike, 1st March 2018

City centrism has become an enduring, dominant and familiar narrative and policy mix. Portrayed as an account of necessarily connected events, it has been generalised into an international recipe for urban prosperity via a myriad of identifiable and high profile academic gurus, international agencies, and think-tanks. Simplified and repeated into messages that can be understood and implemented by national and city policymakers. In short, fix the city centre and the economic growth will trickle-down throughout the wider city-region. City centres are interpreted as the principal engines of economic growth and dynamism for their wider city-regional and, ultimately, national economies.

Economic logics and policy repertoires

The economic logic is based upon ‘external economies of agglomeration’ generated by thick labour markets of educated and skilled labour, spill-overs of innovations and knowledge, market size effects, and linkages amongst associated goods and services activities as the route to higher productivity, economic growth, innovation, incomes and prosperity in cities. Drawing upon urban economics, especially its US varieties thought-up and derived from the empirical experiences of US cities, primacy is given to urban scale, density and economic integration between cities and their hinterlands to reduce geographical and social frictions and enable rational sorting of people and capital over time and space. Policies that work with the grain of this dominant logic are favoured including planning liberalisation, education and skills upgrading, facilitating labour mobility and bringing places closer into their central city growth orbits, often through improved ‘connectivity’ and intra-city transport connections, and business and political leadership and devolved powers and resources to the city-regional scale of ‘functional economic areas’.

City centrism isn’t everything for urban growth

Emergent research from the ESRC-funded city evolutions research project into the urban predicament in British cities since the early 1970s raises some difficult issues for city centrism . Demonstrating markedly divergent pathways in output and employment, southern cities have grown faster than northern cities and large cumulative growth gaps have emerged since the early 1970s. While London’s turnaround since the 1990s is a particular and atypical case, elsewhere smaller and medium-sized cities have outperformed larger cities. City centrism, then, doesn’t appear to work for all cities everywhere all the time. Taking a longer-term evolutionary approach can help us understand when, where and why agglomeration as well as other factors such as their functions and non-spatial public policies may be important for certain economic activities and cities. It can also prompt us to look again and more closely at the relationships and transmission mechanisms of city centre growth to adjacent and outlying areas. For some city-regions, these seem to have been intermittent, weak or close to non-existent since the early 1970s. As the prospects and prosperity of British cities continue to diverge, the difficulties intensify of addressing those cities struggling to adapt and the people and places ‘left behind’.

Productivity growth is not guaranteed with services and scale

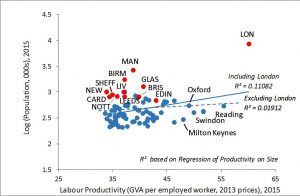

On city productivity growth, northern cities led during the 1970s and 1980s through manufacturing specialisation until their struggle with deindustrialisation led to a switch to southern cities from the 1990s https://www.camecon.com/2017/11/28/geographical-dimension-productivity-problem/. Yet the more service-based growth of southern cities has been less productive, slowing national average productivity growth, despite their relatively higher levels of skilled workforces and knowledge intensive business services. City centrism in Britain appears somewhat skewed towards a paler, lower productivity variant than elsewhere. As Figure 1 shows, there is only a weak relationship between city size and productivity . Scale and density are not always and everywhere the key determinants of city growth.

Figure 1: City size and labour productivity, 2015

Source: ESRC City Economic Evolutions project

Transition to a particular kind of urban service economy has been integral to this productivity slowdown, and cities have largely left any remaining urban manufacturing to fend for itself. Rather than relative neglect, analysis could be much more open to the possibility that the role of diseconomies of agglomeration may have been underplayed in this uneven city productivity performance as unbalanced spatial concentration has stoked more rapid price inflation of factor inputs in land and labour markets, negative externalities in congestion and pollution, and rising costs of infrastructure provision at least partly due to escalating urban land values.

High skilled employment and agglomeration are necessary but not sufficient for city growth

On city skills, city growth and high-skilled occupations are closely related. Skilled workforces are critical to growth with higher levels and faster growth in southern cities. Northern cities experienced slower growth of higher-skilled and greater hollowing-out of middle-range occupations. But the city centrism propositions of ‘smart cities becoming smarter’, and a positive relationship between agglomeration and high skilled employment growth do not appear to apply to British cities. Other factors have been more important and newer, smaller cities have led the pattern of high-skill growth. The urban service economy has become profoundly polarised in occupational terms. Yet, policies are sometimes overly focused on the higher-end jobs, occupations and people when they will only ever constitute a relatively small, albeit highly productive, part of the city economy. While the lower-end of the labour market which employs lots of people but has weak productivity is relatively neglected when its potential for productivity growth could be at least examined more thoroughly. Issues of job (re)design, progression and rotation in sectors such as leisure, retail, and social care could readily be addressed. Reducing the reliance upon thinking that is conceived from a particular US perspective and draws heavily upon empirical data from US cities might be a way to recover traditions of urban and regional analysis better able to explain the particularities of the British urban system.

Time for some fresh thinking?

Some deeply invested in city centrism may dismiss or fail to engage with this more finely drawn picture of city economic evolution in British cities and its challenge to the existing policy repertoire. Some will no doubt continue to argue and marshal evidence to show that it has not failed but has simply not been applied effectively, consistently or strongly enough: that most British cities are still too small and not dense enough, that insufficient emphasis has been given to attracting highly skilled people, that less skilled people have not been given sufficiently sharp incentives to sort themselves (out) and move to where the opportunities are located, that intra and inter-city transport networks are still not extensive enough, and that planning should have been further relaxed to encourage private investment.

Yet, the magnitude of urban concerns in Britain after twenty-five years of city centrism suggests a more self-critical and reflective response, even a little soul searching. Is it time, then, to ask whether an overly narrow and singular focus upon city centrism has reached its limits? In the same way that we can look back at the other US imports of urban motorways and suburbanisation rife in the 1960s as historic and not entirely successful recipes for urban development in Britain, will we consider city centrism in the same way in the years to come? Can we think more broadly and imaginatively about different geographies of urban and regional development that better reflect the emergent international patterns and dynamics of city economic evolutions in urban archipelagos, patchworks and mosaics rather than simple and binary cores and peripheries? Countries across the world are experimenting with new metropolitan and other wider scale, pan-city-regional geographies in attempts to tackle the thorny problems at hand. Finding better ways to think about and design policies that support the combination of the dynamism of city centres with their hinterlands to the benefit of both is a pressing challenge for those thinking and doing city economy and policy.

Andy Pike is the Henry Daysh Professor of Regional Development Studies at the Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies (CURDS), Newcastle University, UK. He is part of the ESRC-funded project on City Economic Evolutions led by Professor Ron Martin at the University of Cambridge and involving other colleagues in Cambridge and the Universities of Aston and Southampton, and Cambridge Econometrics.