Posted by Peter O’Brien, 22nd July 2014

Readers of the CURDS blog series will be aware that, as part of the national EPSRC and ESRC-funded iBUILD Infrastructure Project (https://research.ncl.ac.uk/ibuild), CURDS is conducting research into the governance and regulation of local infrastructure funding and financing. Two recent reports produced by the RSA City Growth Commission and the Institute for Public Policy Research (ippr) examine the role of infrastructure in local growth and development, and together pose questions about how we define and measure the value of urban infrastructure.

Last week, I attended the launch, in London, of the City Growth Commission Report Connected Cities: The Link to Growth, the latest publication by the Commission that is investigating the growth potential of UK cities, chaired by the former Goldman Sachs Chief Economist, Jim O’Neill. The report, which cites the activity of iBUILD, claims that “high quality infrastructure is a critical driver of productivity and growth”. Few would disagree with this statement, although economic geographers would also suggest that infrastructure is not the sole determinant of productive local and regional economies, as the OECD affirmed in its 2012 study, Growing all Regions. Rather, infrastructure is one component of successful development strategies, alongside human capital, innovation, enterprise and effective institutional governance. However, policy-makers and researchers are understandably seeking to acquire greater knowledge and understanding of how and where infrastructure drives particular forms of growth and development, and how public and private infrastructure investment decisions can be better informed by technical appraisal and assessment.

The Growth Commission rejects what it calls the current “inefficient, centralised model” of local and regional infrastructure investment and governance, and outlines five recommendations for change:

1. The development of a stronger, urban-focused Infrastructure UK.

2. The creation of a fairer and more flexible funding system based on fiscal devolution to cities and city regions.

3. The introduction of a flexible and innovative planning system.

4. Better appraisal techniques that reflect more accurately the costs and benefits of infrastructure investment.

5. Strengthening of city governance and local government capacity.

The Commission also identifies a critical issue that was flagged up in a previous CURDS blog on Fiscal Devolution, which concerns how UK national accounting frameworks should measure and interpret certain forms of local growth as additional contributions to the national economy and not as displacement between local areas.

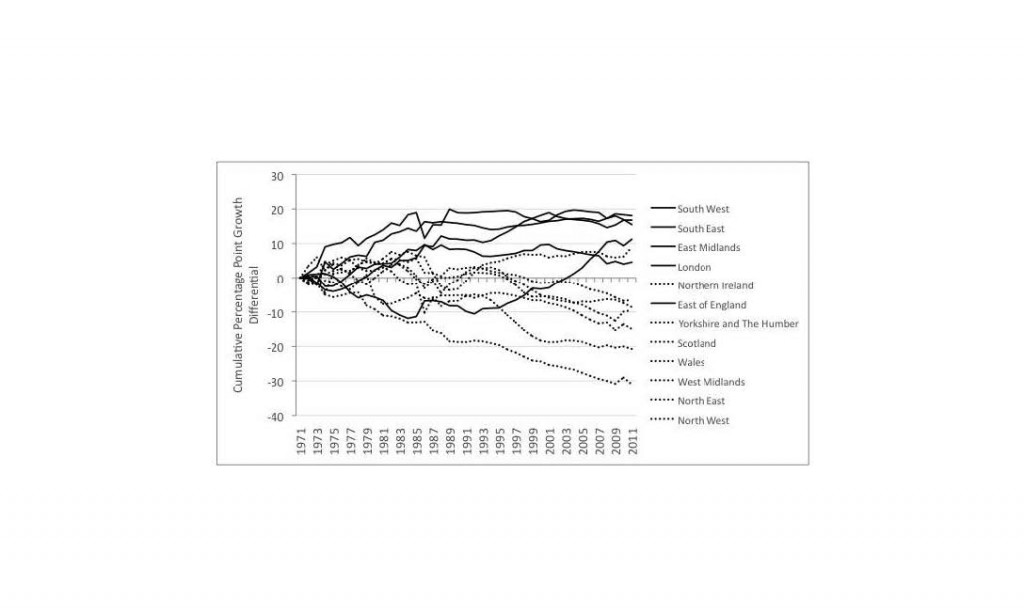

One of the Commission’s headline proposals is that, as a counterbalance to London and the South East, investment in transport infrastructure between northern cities should be prioritised, in an effort to create a large ‘alternative agglomeration’ in the north of England. This differs from the conclusions reached by other studies, such as the Eddington Transport Review in 2006 and the Manchester Independent Economic Review in 2009, both of which argued that transport investment within cities should be the immediate priority.

The Growth Commission’s work is a useful and timely contribution to the existing discourse on cities and infrastructure. However, very little is said about the social and environmental value of infrastructure in shaping, making and re-making urban economies and places. Whilst the report is accurate in its assessment that the private financing of infrastructure in the UK has, in part, led to fragmented or splintered urban infrastructure networks, the Commission could have been more explicit in its critique of the current market failures in infrastructure planning and investment. The report, for instance, could have highlighted how cities outside of London require a consistent policy line from Central Government on urban transport management and governance if they are to assume greater responsibility for the planning, funding, financing, delivery and regulation of local transport infrastructure. For example, Whitehall views London’s bus regulatory and over-sight system as a success, but the Government is seemingly reluctant to show the same level of support for similar models being advocated in other urban areas in England.

The baton on cities and infrastructure ownership and control is picked up by ippr in a new report, City Energy: A new powerhouse for Britain. The report suggests that cities could play an important role in fixing what the think-tank calls the ‘broken market’ in the UK’s energy sector, which, as the Public Accounts Select Committee concludes, is demonstrated by the fact that consumers are paying (and are forecast to continue to pay) higher bills and therefore disproportionate contributions towards industry capital investment.

In the past, UK cities were responsible for building and maintaining infrastructure assets, reflecting what Adam Smith regarded as the third duty of government. Recently, cities, such as Munich (referenced in the ippr report), Melbourne and New York, have developed new forms of community and public urban renewable energy provision. In 2013, voters in Hamburg agreed to the city’s energy grids being brought back under public ownership, part of a broader trend that has seen 170 German municipalities, since 2007, buy back energy grids from private companies. The citizens of Boulder, Colorado, USA, have also agreed to move the city’s energy grid into municipal ownership despite strong opposition from the state’s largest utility company.

The Greater London Authority and members of the Core Cities Group are keen to enter into the energy supply market, and ippr believes that there are five business models that London and other UK cities should consider:

1. Fully licensed supplier: a city sets up and runs an independent supplier, taking full responsibility for delivery and meeting licence conditions.

2. Joint venture: a city works with one or more third parties to set up and run an independent supplier.

3. Licence-lite: a city becomes a ‘junior supplier’ with responsibility for some aspects of delivery and meeting licence conditions, while a partner ‘senior supplier’ is responsible for the rest of the business.

4. Partnership: a city works in partnership with an existing, licensed supplier and takes responsibility for some operational aspects of the supply business in its area.

5. White label: a city licenses use of its brand to an existing supplier who uses it to market to customers in the local area.

On the vital question of funding and financing, ippr recommends that: cities work with the Green Investment Bank on low carbon energy investment; cities support the Local Government Association’s proposals to establish a collective Bonds Agency; the fiscal rules laid down by Treasury should be designed to ensure that debt for local authority capital expenditure does not count against legitimate targets to bring current spending back to balance in the medium term; and local authority pension funds should comply with the Principles for Responsible Investment.

The ippr analysis adds additional weight to the assertion that how we choose to define and measure the value of infrastructure can shape public, private and community involvement and participation in infrastructure planning and delivery. Although most UK infrastructure is privately-owned, there is an increasing international trend of private infrastructure assets, particular in the water industry and energy sector, returning to public ownership. The move to (re)municipalisation is driven, in part, by the failures of existing regulatory arrangements, and other factors, including:

• Concerns about the funding of infrastructure in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis.

• A desire on the part of governments to achieve public service and community objectives.

• A move to rebalance stakeholder and shareholder interests.

• Notable private sector failures in infrastructure provision and delivery (particular in management and corporate governance).

• A call for greater transparency and openness in procurement, investment and finance decisions and plans.

• Greater regard for environmental and sustainability considerations.

• Recognition that infrastructure is a broader societal and economic asset.

• A move by cities to re-think the use of public realm and spaces within urban contexts.

Professor Dieter Helm, an infrastructure expert at the University of Oxford, claims that the issue now is not whether the state should intervene in infrastructure, but how. In CURDS, we would also declare a specific interest in identifying where the state should deliver interventions within and across different spatial levels. These questions, along with others, are providing some of the context for new research by Glasgow University’s Professor Andy Cumbers on alternative economic strategies and infrastructure ownership models. A deeper exploration of these intricate patterns and processes, drawing upon emerging analysis and initial findings from the iBUILD project, and parallel CURDS research on cities and devolution, should help us to arrive at a clearer definition and measurement of the economic, social and environmental value of urban infrastructure assets and systems, which ultimately will then inform crucial long-term investment decisions.