by Ashleigh Kernohan

So you’ve tried everything. You’ve blinked about four hundred times, you’ve rubbed with a tissue and you’ve gone to town with that rough part of your sleeve but it’s no use. You’ve definitely got something stuck in your eye.

If you were to wake up tomorrow with this particular problem, then the best course of action may vary depending on where you happen to be. If you are in Newcastle there is a walk in hospital eye clinic which you can attend. In Manchester you would attend your GP who would send you to an accredited optometrist who may help you in their practice or then refer you to hospital depending on your problem. If you were to travel north to Aberdeen then it is possible to be referred from one optometrist to a different optometrist with a local protocol to give medications, who may still refer you to hospital depending on your problem. One could be forgiven for being confused about what to do in this situation, particularly as you are trying to navigate this pathway with one eye.Community management of eye disease became the focal point of my own thesis; particularly pathways which utilise community opticians to manage eye disease (as described for Aberdeen above) compared to hospital based medical ophthalmologists (as described for Newcastle). When evaluating pathways to manage acute eye diseases one particular difficulty that was encountered was trying to value the outcomes. There are particular challenges when eliciting preferences from temporary, unexpected and painful health states.

Valuing the sudden and the painful

When trying to elicit preferences from those who are suffering from acute problems there are two main difficulties: firstly, the unpredictable nature of these conditions makes them difficult to sample. If you need to survey diabetics there is a very good chance you will be able to find some (from GP surgeries or outpatient clinics for example). If you need to survey someone with a broken arm, you have little choice but to stake out A&E and wait. This is also true of eye problems; it is very difficult to predict when a cornea will succumb to an infection or a piece of wayward grit may lodge itself in an eye. Therefore sampling often relies on a combination of luck and patience. This is particularly true when there are number of different avenues in which a patient may access care, as described above.

Secondly, measuring the effect on quality of life in someone who is currently in an unexpected amount of pain and distress can prove difficult. There is a time constraint in getting the problem solved which does not lend well the rigor of academic research. Asking someone who currently has severe pain in one eye to complete a five page quality of life questionnaire is not likely to be met with a great deal of compliance or enthusiasm. This means that for pragmatic reasons either a retrospective approach (survey they participant after the condition has resolved) or a very simple measure such as a visual analogue scale (VAS) can be used. The VAS asks individuals to rank their health state between perfect health and death using a scale like the one below.

Both have their advantages and disadvantages. The retrospective approach has the obvious disadvantage that the participant might not remember the event with the same clarity after it happened. Particularly if the problem only lasted a few days or weeks. The disadvantage of using a very simple measure, like a VAS, is that that the results may lack the generalisability or reliability of a more nuanced measure.

Preference elicitation for temporary health states

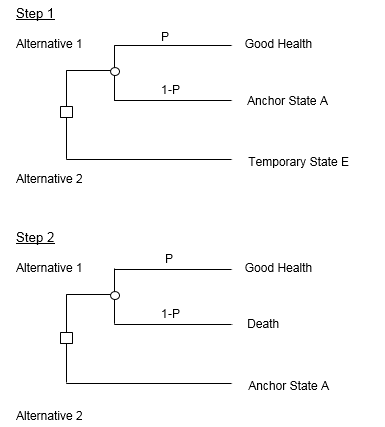

If capturing quality of life data experimentally proves infeasible then another option would be to carry out a preference elicitation study to value the painful eye problem. This approach also has its challenges. Ogwulu et al. carried out a systematic review of the current literature on techniques used to value temporary health states. They found that there was no consensus on the most reliable approach to value temporary health states, with most studies using multiple measures and lacking reliability. The approach that we took when valuing a painful eye disease state that lasted one month was a chained standard gamble approach. A standard gamble introduces uncertainty to the task of rating one’s health. A participant is given the option of living in a less than perfect health state or an uncertain risk between full health and death, the amount of risk the participant is willing to accept informs the utility value. When valuing a temporary health state the technique is adapted to add an extra question. It is unlikely that an individual is willing to risk death for a temporary health state so level of risk is assessed against a state less severe than death (but more severe than the temporary health state being valued) known as an anchor state (which in our example was a state of blindness). This anchor state is then valued against a risk of death which allows a utility value to be calculated. This process is shown in the diagram below.

Diagram adapted from Brazier et al (2017)

The main drawback of this approach in the four week long acute eye disease example was it required participants to hypothetically gamble with their last four weeks of life. This led to a lot of consideration about setting affairs in order and spending time with family members which affected the resulting utility values in ways which had little to do with the eye condition being valued. We hope to publish the results of the study later this year.

Many acute and painful problems have established solutions, so they are not always subject to economic evaluation. Yet, as demonstrated in the example of corneal foreign body described above the way of accessing these treatments may still have significant resource implications. So although it has its challenges, further research in the area of valuing acute and temporary health problems is worthwhile.

References

Brazier, J., Ratcliffe, J., Salomon, J. and Tsuchiya, A. (2017) Measuring and Valuing Health Benefits for Economic Evaluation. 2nd Edition edn. Oxford University Press.

Ogwulu, C.B., Jackson, L.J., Kinghorn, P. and Roberts, T.E. (2017) ‘A Systematic Review of the Techniques Used to Value Temporary Health States’, Value in Health.