Category Archives: Blog

OHD_BLG_0254 Blog post on the first month at NCBS

From a lively archive in Bangalore

Between indulging in delicious food and gandering around the stunning campus of the National Centre of Biological Sciences (NCBS), I sit at a hot desk in the basement where the Archives at NCBS is housed. The term ‘basement’ is slightly misleading as the sun shines through windows which face a sunken outdoor amphitheatre, where I can watch paradise birds flirt with each other in the trees. When not distracted by birds or food, my attention might be drawn away from my work by one of the eleven other people working in the Archive. It is the loudest archive I have ever been in, even when I discount the constant humming of the air conditioning. It is also the most welcoming workplace I have ever worked in. The Archives at NCBS is a hub of multidisciplinary folk, all coming together to build this archive, which is still very much in its infancy, celebrating its fourth birthday on this month. Therefore, a lot of the work is focused on growing the archive, with some team members creating a digital catalogue, others expanding the collection, and many involved in developing the various work flows necessary to keep an archive running.

This development of workflows, which I am also playing a role in, is necessary because, like so many organisations in the GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives and museums) sector, the Archives at NCBS is working within the grant cycle. This automatically leads to a lack of consistency under the staff and therefore creates a somewhat unsettled work environment. From February 2019 to February 2023, around 60 interns have passed through the archives’ doors. When I started my conversations with the head of the archives about doing my placement here, the archives team was three people. Now it has grown to twelve, including two archivists, a software developer, various artists in residence and an outreach team. There are also several other researchers who use the Archives’ reading room and offices to work in. What I am witnessing within the walls of the NCBS basement is how the sudden expansion and change within the archive is causing some growing pains. These growing pains should not be considered a negative, but as part of the natural process of building an organisation. They are what is motivating the development of various workflows.

Developing these workflows is necessary because, while the previous team of three were easily able to know exactly what the others were doing, the current members of the archive team are slightly less sure, even though they are all in the same room. By creating workflows, the workers of the archive, new, old, temporary, and permanent, will be supported in their work, allowing the larger work of the archive to be carried easily through the grant cycles and revolving door of many interns. However, this is not an easy task, especially when everyone still needs to carry out their day-to-day work alongside the workflow development. I am, therefore, doing my bit by creating the archives’ notice and takedown workflow. I am looking into how the archives can edit, redact, and remove archival material and capturing this process in a way which is helpful for users of the archives and present and future archivists.

While overall my first month in India has been delightful; filled with lovely weather, delicious food, and a group of generous and considerate co-workers, I will admit it took me some time to find my feet in the work at the archive. At first it was not clear what I should be doing, but now, with the development of the takedown workflow, I have been given direction, and am glad to be here to help the archive through this unsteady and nebulous time. The Archives at NCBS might not know exactly what it is doing right now, but that is okay; no one really knows what they are going to be at the age of four.

OHD_BLG_0034 21st Century Ghost

Have you ever heard of the twenty-first century ghost? You have definitely seen it and heard it. It hides in many places, but its favourite spot is in the pocket of your trousers, next to you on the table or in the palm of your hand. The ghost of the twenty-first century lives in the interactive rectangle that is your smart phone. This ‘digital urn’, as described by Kirsty Logan in the podcast series A History of Ghosts, is filled with your voice, your face, your ideas, your questions, your life. Every day we work on growing our own twenty-first century ghost by feeding it incredibly personal information and preserving it in our digital urn. But our twenty-first century ghosts’ range is not limited to our smart phones, they spread across the world, roaming around social media servers and traveling in the inboxes of other people’s digital devices. The average person has no control over what can be found in their digital urns, what past lives the ghost can expose and havoc it can cause.

Some people have a different type of ghost, one that is a little more timid and introverted. If you have ever taken part in an oral history project you probably have such a ghost; a recording of your life’s story told by you living in an archive staying put until someone calls on it. In order to put an oral history interview into an archive and create an archival ghost, one has to fill in what seems endless ethical approvals, consent forms and permission slips. These documents are there to highlight the potential “dangers” of having something in an archive: how you privacy might be violated or how someone could misuse your testament and twist your words. Social media sites do a similar thing, only they condense the stacks of paper into one tick box. Clearly the archiving process is more transparent in comparison to the methods use by those in the Silicone Valley, which at best are questionable and at worst violate basic human rights, however transparency does have its drawbacks.

The reaction people have to this transparency is similar to that when you ask some people to travel by air. People are terrified of flying because they are fully aware of how wrong it can go, but statistically it is a lot safer than walking to the corner shop. Just like the designing an aeroplane, archiving an oral history has to follow certain rules from the start, because those involved, aerospace engineers and oral historians, are fully aware of the chaos and pain it could cause if the systems fail. Having these restrictions is seen as more ethical, but it also inadvertently puts disproportionate emphasis on the dangers of archiving (and flying). In opposition, walking, like the ticking of the terms and conditions box, is easier and it delivers blissful ignorance to the high probability of being hit by a car or having one’s data stolen. Unlike the oral historians and archivists, the developers of the uncomplicated tick box view their users as nothing more than data sets and potential profit. Some could say that this has led them to be dismissive of a human’s right to privacy and be vague when it comes to revealing the true cost of using one of their platforms. However it seems that by not drawing attention to terms and conditions, people have become very happy to hand over their personal information.

The existence of these two ghosts, the restricted and timid archival ghost, and the free and uncontrollable twenty-first century ghost, makes the people’s relationship to their privacy seem incredibly distorted and ill-informed. It seems odd to trap the archival ghost with paperwork in order to protect their corresponding human, when that exact human is completely content with sharing every single part of their lives with strangers on the internet. However, it is this sharing that is key to success of social media. By giving up their privacy the users of social media are granted access to a huge network of listeners and viewers. After all a story is not a story if there is no one to listen to it. By the same logic if the oral history is never reused, the archival ghost is never called upon and the story is never listened to, its very existence becomes void. So this raises the question: should we even bother archiving oral histories in the first place if the paperwork blocks it off from listeners? For the sake of my research we’ll say yes, in which case let’s follow it up with the question: should we be more like Silicone Valley and be a little less pedantic when it comes ethics?

For now I am going to go with yes and no. The current process around ethical archiving does need updating but because I also fundamentally believe that Silicone Valley is wrong and I think people are starting to catch on. People are becoming increasingly aware of what their twenty-first century ghost might expose. For example, a growing number of people are being ‘cancelled’ because the public have dug through their digital urn and found a tweet they sent when they were twelve and used a term that is now considered very derogatory. There is also a generation of people, who are unhappy with their parents relentless ‘sharenting’. Sharenting is the practice of posting everything your child does online, which results in the child having a data presence before they can even speak and therefore give consent to its existence. This faint atmosphere of mindfulness around posting, uploading and sending is descending over the digital world. People are reflecting on the ghosts they have created and are now trying to do damage control.

Currently the archival ghost and the twenty-first century ghost are two extremes on the scale of privacy and its corresponding ethics. However, the increased awareness around the rabidness of the twenty-first century ghost is pushing it along the scale in the direction of the archival ghost. I believe it is now the turn the archival ghost to make a similar move towards the centre. There needs to be more innovation when it comes to the ethics of archiving because at present it is stopping people listening back and that is truly a shame. People bond over sharing stories, they create communities around the most random of things and social media proves this. However social media also showcases perfectly the consequences of condensing very complicated ethics into one tick box for the sake of ease. Changes need to be made on both sides of the scale. By observing the current situation on each side, investigating the pitfalls, challenges and opportunities, and reviewing how different people in the respective fields are attempting to solve these problems, we can start seeking an equilibrium and find a balance between private and public. This managing of our ghosts is a strange and distorted process that is only in its infancy, but hopefully by the end we will be able to free the locked up archival ghost and calm the twenty-first century ghost.

OHD_BLG_0039 It’s not my problem

There is a problem within the National Trust’s storage system (SharePoint) that is sadly a consequence of democratisation. SharePoint is a complete mess and no one really knows what is going on or who to ask about what is going on. And although this has a lot to do with the design of SharePoint and the lack of transparency surrounding the structure of folders and such, there is another reason there is so much chaos in the folders and that is control. You see before this chaos took hold it was the collection staff who would have been in charge of the archival and collection material, while others might handle files concerning business. Information would have been kept on people’s shelves in their offices, and so to access this information you would have to go through a human. This might in some cases be really annoying because the person who could grant access wasn’t feeling up for it. But then the internet came along with the main intention to make information free and accessible – a more democratic system. Like everyone else the National Trust also decided to remove its strict system of gatekeepers and adopt the attitude of the internet. And this is where an unforeseen consequence arises because while before one person was responsible for a file, now everyone is responsible for all the files, there are no parameters. And because everyone is in charge of looking after everything it is really easy for the individual to simply hope that the next person will sort out that file. Also because looking after files is maintenance and people do not like doing maintenance. Now do not get me wrong I agree that we should have better access to archives and no has the right to deny someone access, but in a world where everyone is responsible, no one is responsible and the National Trust’s SharePoint proves this.

OHD_BLG_0041 The winds of change are blowing…

I feel there is a change in the wind… Specifically people are starting to think more long term about their projects, they are becoming more archive focused. This is not too surprising there is a reason my PhD is happening now and not earlier. Timing is everything when it comes to research and people from different fields have invested in this PhD which they would not have done if it was a ridiculously radical idea. But crucially funding bodies also seem to be changing their tune slightly. I was pointed in the direction of the National Heritage Fund’s new programme, Dynamic Collections. According to their new campaign:

Our new campaign supports collecting organisations across the UK to become more inclusive and resilient, with a focus on engagement, re-interpretation and collections management.

THE NATIONAL HERITAGE FUND

Sounds pretty promising if you ask me…

OHD_BLG_0042 What do you mean not digital?

Whenever I mention my ideas for analogue archiving solutions to anyone the reaction I get is a blank stare shifty follow by a change in subject. When I was venting about this recurring experience to my mother, she did not seem surprised; “what do you except people see the digital as the future?” She is correct this is what people believe but the ‘future’ is a rather nebulous concept and it is important to manage expectations – how far is the ‘future’? If you take what is written in The shock of the old: technology and global history since 1900 then you will quickly understand how far off we are from the future and how slow technology actually moves. The writer approaches the history of technology not through the lens of innovation but from use – a use-based history of technology. This quickly reveals the pace at which humanity really adopts technology through examples like horses being more important in Nazi Germany’s advances than the V2 and the fact that we have never used as much coal as now. We are slow at technology, which is fine but we need to be aware of it. The digital divide is a real thing and it needs to be considered. Note that the digital divide is not across generational lines, yes older people cannot use TikTok, but I have seen children struggle to use a keyboard and a mouse because they are so used to touch screens. The digital divide also means that there is an exclusive group of people who do know how to use this tech and they are in high demand, to the extend that there is little incentive for workers to lend their services to the GLAM sector. Why would you work for less money in a library when you can earn a hundred times more somewhere else. Heritage sites and the wider GLAM sector can in many instance not afford to develop their own technologies mostly because they are unable to maintain them. But they also sometimes struggle to update their bought in systems because moving all their data on their collection round is too much work and effort. And in some cases the software producers are aware of this and shut down the feedback loop because they know their customers can’t leave them. To summaries saying “digital is the future” is an unproductive lie that we tell ourselves to make us feel better and trendy.

Here comes my suggestion otherwise we would be left hanging in a rather sad place. The National Trust is undoubtedly a large organisation and they already run several digital platforms which they have their own maintenance team for. What I suggest is that if people want to create cool snazzy digital interfaces they have to do this at Trust, because the Trust already have the infrastructure in place (to certain extent) to cope with the difficulties of running a digital system. E.G. https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/rijksstudio On individual site level however digital platforms cannot be made or maintain and the only option in my eyes is to either to keep it analogue (better for the environment) or DIY digital. By DIY digital I mean word docs and spreadsheets and softwares that are a little more accessible to a wider group of people. These option are more accessible and more maintainable but they are less sexy. When it comes to working with digital you have to know your limits and the people around you and the people who will come after you. It is not exciting but it might just solve your problem.

OHD_BLG_0043 Philosophy is easier than reality

On Monday 11th April 2022 I attended and ran a workshop at the Seaton Delaval Hall Community Research Day. It was an exceptionally interesting affair and mostly certain did not go the way I imagined. If I had to sum it up I would describe it as engaging but impractical. To say that it got deep real quick would be an understatement but the to which it went was fascinating. It was also great to just bounce ideas off people. However it felt like whenever I attempt to move the conversation to getting to more practical solutions people rather stayed in philosophical and imaginary realm or they would just explain why it would not be possible to change that.

Maybe I am too much of a designer, wanting to think of solutions instead of sticking to the status quo. Or maybe this is exactly what I should be doing, building a bridge between the imaginary realm and the real world. Maybe this is the point that Verganti talks about when he discusses ‘Interpreters’. The people in that room on Monday were my interpreters, the people I can draw on for inspiration and ideas…

If this is the case it is now my job to turn the “multi-verse” of history that we kept talking about into reality. No pressure….

OHD_BLG_0044 To archive or to exhibit: A SPECTURM

This is the thing: WE CANNOT ARCHIVE EVERYTHING. We do not have the room or the resources. Now, one can think that in the case of oral histories that maybe we should not go around recording everything, especially when recordings have already been done of that community. An example of this that was recently mentioned to me was Chinese people in Soho, London. In America the Oral History Association warns people not to record people or groups that already have been recorded. In the UK however there is no such thing. Funding bodies AKA the people who own all of our heritage, do not care if a project has already been done, they only really care about community engagement (good for PR). This means people do projects that the people want to see, which is find but the public has bad taste and often just wants to see the same things over and over again. From an archiving standpoint this is not super fun. However I think there are two things I think we can do.

Firstly, archives need to be more picky. I know that this is super dangerous but there is a difference between having a lot different types of shoes and just having the same shoe multiple times. Archives should not be the dustbin of history because we cannot afford that resources to keep everything afloat. The second thing I think we can do is encourage more exhibiting of project results. So instead of archiving, people just exhibit their work for a set amount of time and then after that it is no longer available. You can then do an oral history of the project later on if you wish to do so. Another option is to only archive the exhibit and not the raw oral history recordings, this will probably also save space and time. Either way I believe it is always good to think about these things before you record your oral histories, even if it is just about managing expectations.

OHD_BLG_0045 Leaching off Public History MA trips

Two thing I learnt while tagging along with the Public History MA trips to various heritages sites.

Chasing funding

We went to three different heritage sites of varying status and every single one of them mentioned funding many, many, many times. Like many things in the world money is the foundation of any project, endeavour, or system, without it nothing happens, even in the heritage sector where a considerable amount of the labour is free because of volunteers. The majority of funding is project based. That means you write a proposal for a project, which has target outcomes and needs to be completed in a set amount of time. Once the project is finished and you have used up all the funding you have to go look for another project and a new funding. This is often referred to as the funding cycle. The funding cycle is not necessarily good in supporting legacy long term projects. “What will happen when the funding runs out?” is constantly looming over any project and many people actually spend a lot of time writing funding bids instead of working on projects. I therefore not the greatest fan of the funding cycle but there was one person we talked to during the week that gave me a new perspective on the whole thing. They said that the funding cycle allowed them to constantly be reflecting on their practice and what they should be doing next. This is interesting to me because reflective practice has been taught to me as a new and innovative groovy thing. New systems keep on being developed in order to incorporate more reflection but in the funding cycle it has always existed, kind of… It is probably a lot easier to have this attitude when you know you are going to get the next funding anyway, which this person definitely did.

Democratisation of Space

The second thing I realised/changed my perspective on during these trips was how you can view a lot of the politics through the idea of “whose heritage is it anyway?” but somehow I realised that it might be helpful to view it within the context of space and ownership of space. This is quite common in art I guess as people often talk about who gets put in certain gallery spaces and who does not. Every group has their history which they can keep but where it is displayed is where the power truly lies. Sure you can have a history of black people in the black history archive but a far more powerful space to have the exhibition would be the British Library or National Gallery. My theory is: that when we talk about democratising heritage what we really are talking about is democratising space. How can we represent our multilayered history in our limited heritage space? I am thinking that the answer is probably something along the lines of nonpermanent exhibitions…

OHD_BLG_0046 the nerd filter

The nerd filter is an idea that I have been mulling over for a while now. The basic principle is that you gain more access to an archive the more time you spend in the archive and interacting with the archivists. In other words as you get more integrated into the community of the archive you are able to view more sensitive documents. I see it as a type of social trade. The user invest their time into the archive and exposes themselves to the eyes of the archivist and in return they gain trust and access to other documents. The reason it is called the nerd filter is because those who are not as passionate or “nerdy” will eventually give up and leave the archive community. The people who are then left behind are the proper nerds, who have a significant amount of social capital with the archive. My theory is that these leftover nerds will be more responsible with archive material because they risk losing the access they worked so hard for if they betray the archive community.

It is like a type of loyalty card scheme, but whether it will be taken on by archives is another question…

OHD_BLG_0047 Delete as appropriate: Bad/Good Slow/Fast

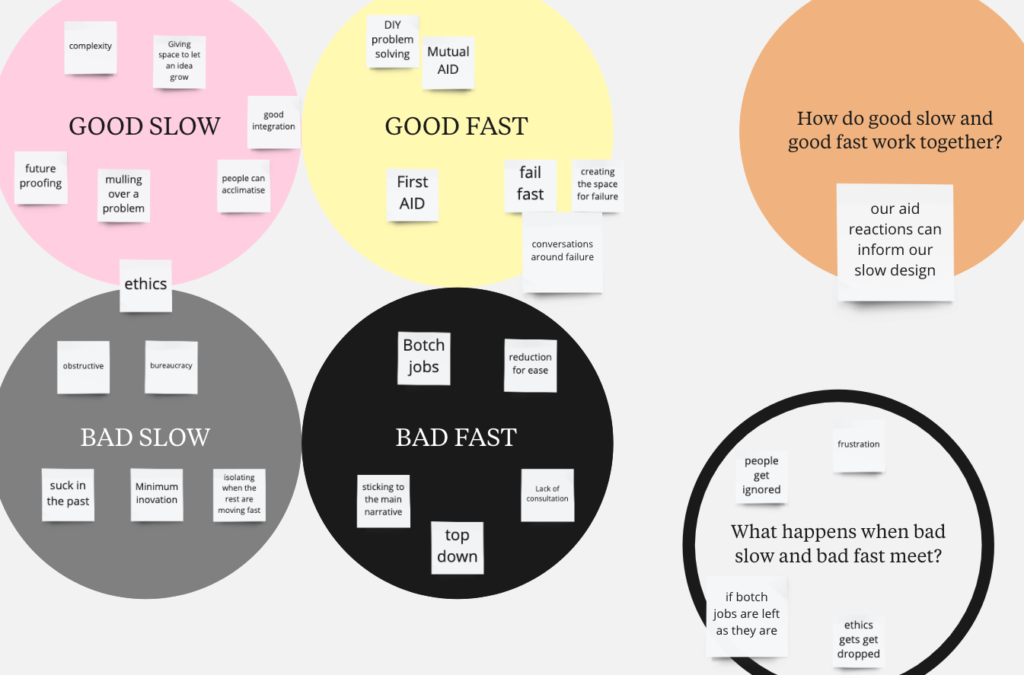

Two weeks ago I had a chat with Ollie Hemstock from Northumbria University about Slow Design. We discussed the benefits and downfalls of slow and fast design and eventually wondered what makes fast good and what makes slow good. So I took up the challenge of defining good fast and good slow, and while I was at it, I also defined bad fast and bad slow. Making myself a little online mind-map I speedily popped down virtual post-its and quickly discovered that what makes a speed good is also sometimes the reason why it is bad.

- Good Fast – Creative thinking under pressure, Google Sprint, First Aid. No overthinking. Magical solutions. Fail fast.

- Bad Fast – Drawing on stereotypes and single narratives. Reducing information, and a lack of consulting. Can do damage.

- Good Slow – Allowing ideas to grow. Future proofing. More room for nuance and complexity. Ethics.

- Bad Slow – Obstructive bureaucracy. Sticking to the past. Minimal change.

Fast does not give you enough time think, which makes things less complicated but also reduces information and abandons nuance. Slow makes loads of room for nuance but can block change in fear mistakes. One is therefore not better than the other. But what happens when we combine the two.

Good Fast + Bad Slow

Good Fast is blocked by Bad Slow killing innovation. Good Fast means testing and failing fast but Bad Slow would put a stop any testing.

Bad Fast + Good Slow

While Good Fast is blocked by Bad Slow, Bad Fast and Good Slow stand in complete opposition. They simply cannot happen at the same time. Bad Fast is bad because there is little thinking, while with Good Slow there is loads of thinking. These two cancel each other out.

Bad Fast + Bad Slow

In this combination someone quickly solves a problem but then does not go back to reflect on it. For example someone does some botch DIY which works at first but really needs a long term solution, however bureaucracy and rules are blocking that long term solution from happening.

Good Fast + Good Slow

Instead of being blocked by Bad Slow, Good Fast releases information that is then integrated into Good Slow’s thinking process. Here there is an agreement between the two speeds that failure is good for the future but that you need to be able to put the breaks on at any moment. It is the ultimate feedback loop. Like a well run household, because sometimes you need a quick book under a table leg and other times you need to slowly work out where you actually what to put a shelf.

OHD_BLG_0048 The right to repair 🛠

The right to repair is important and connected to my work because like many things in the world it has to do with maintenance. I had a chat with O Hemstock from Northumbria University about slow design and he brought up that maintenance is about agency. It is about the right to repair and the power you have over the objects that make up your life. Having agency means that you can fix it when it is broken, you don’t need to rely on others to fix it for you and you are not forced to buy another. But it is also about the ability to customised and edit and make the object fit to your needs instead of the other way round. It is important to think about maintenance not only because of the planet but because of the effect objects have on people’s lives. For example you want a pan to be good but what if the person burns something in the pan, which they are likely to do because they are human. What do you as the producer of the pan do then? Sure technically the ownership of the pan has moved from one to another but what can you do to help the new owner with maintenance of the pan. Handy youtube videos on how to clean your pan or a cleaning service for example. Now I am aware that the pan scenerio is a bit of an odd one but thinking about maintenance is always a good thought exercise in design.

OHD_BLG_0049 Testing archives

I have realised a rather large problem with my project and that is that it is very difficult for me to test out my ideas. I am essentially building an archive-like system and the true test of an archive is to see how well it stands up to time. Within the time frame of my CDA I will not be able to truly see how well my archive system works both from a user point of view and the maintenance workers.

I wonder if there is any literature on this that could help me workout how to test long term products in the short term…

OHD_BLG_0052 It’s all about the cleaners

I always get frustrated when I clean my fridge. There are so many little ridges that stuff gets into. I even have to have the door of my fridge open a certain way, which is not logical in the day-to-day of opening it but is the only way I can make sure that I am able to take out the shelves to clean them properly. This is an example of people designing a product without thinking about maintenance. The designers were not thinking about the cleaners they were thinking about the users. In a capitalistic and consumer driven world this is not surprising. We want to sell products to the users and cleaners are not important. Cleaning is after all a women’s job and who gives a shit about them. However cleaners are extremely powerful. If cleaners go on strike you have a big problem.

However, cleaners do not generally go on strike. They are often women, who are most likely from a minority background and need the money. Striking is a privilege.

But cleaners are extremely powerful and this is proven by the new types of cleaners and maintenance workers. The computer guys. The IT department. The software developers. However unlike domestic cleaners our digital cleaners are mostly privilege educated men. This in combination with the fact the we view digital as our new god, means that we view these new, digital cleaners in a very different light. These types of digital cleaners are a luxury. Don’t get me wrong being able to employ a cleaner to clean your house is also extremely privileged, but this is a whole new level.

Now some might point out that the digital cleaners need way more training but then I would invite them to clean a university building. To be able to clean fast and well, while simultaneously being completely ignored by your fellow humans and having to deal with the disgusting things that come out of these humans, you need to be really good and have a lot of experience. The most elite cleaners, those who work in very fancy hotels, have to under go extreme training. They are different jobs but one is not harder than the other and the difference in pay a shameful.

But what does this have to do with archives, because that is what I am normally talking about. Well, in this article by archivist Charlie Morgan he talks about Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!, which is one of my favourite art pieces. With her work Ukeles brings to light the people to who have to maintain the work after it has been created. Morgan writes that as a society we are focused on creation and under value maintenance (not surprising as this is either done by women, or the working class.) This focus has led everyone including archives to become obsessed with collection. GIMME ALL THE STUFF! This is like my fridge completely ignores the maintenance staff. How are we going to look after all this? WHO CARES I WANT IT!

Not helpful. Especially when people are handling sensitive informative which many archives do (so does most of Silicone Valley, but that’s another issue.)

My work is about getting people to reuse oral history, to give purpose to the storing of recordings, but I must NEVER forget about the cleaners. I cannot design any thing extremely complicated because most archives cannot afford the luxury digital cleaners. They have to do all the cleaning themselves. Heck, I was talking to an archivist who said the they currently were not doing any archiving they were doing building maintenance. Archiving is not the job you think it is. Archiving is cleaning. Cleaning up the world’s information.

OHD_BLG_0054 Stay Healthy!

We are cyborgs. We are so dependant on our digital devices that we have become cyborgs. I do not even use my phone that much but I am definitely a cyborg. Someone pointed this out during a seminar. They said, “if you don’t believe that you are a cyborg let me take your phone away and then you will realise that you are a cyborg.”

I just read The Unsustainable Fragility of the Digital, and What to Do About It by Luciano Floridi. In the paper Floridi talks about the fragility of the digital and how we need to make sure that it stays healthy because otherwise viruses can spread fast. Linking this with the cyborg idea I realised that we need to start talking about our own “digital health”. The digital is not going away any time soon, so in order to stop the spread of viruses, which can cause enormous amounts of damage, we need to start thinking about digital health. Now this obviously firstly works on the level of software and cybersecurity companies. They are the healthcare sector, but we as individuals also need to work on this, just like we do with our physical health.

We have our bodies (physical health), our brains (mental health), and our digital extensions (digital health). If we are cyborgs then it only makes sense that we look after the robot part of ourselves. Especially because that robot part is only going to grow over time (sadly).

OHD_BLG_0055 Let’s do it slowly sometimes

One of the biggest problems I have discovered while trudging through the world of oral history is that people do oral history projects, make a website, and then that website inevitably dies. This really sucks and is very annoying when it comes to researching. The reason for this is mostly because of funding issues. You get a chunk load of funding for one project and that is it. This (I believe) is due to us living in an extreme capitalist world, which pushes people to think in quick wins rather than long term projects. This is for example the reason that governments and business are hesitant to pursue environmentally friendly options, because it costs a lot of money and the returns will only be seen way down the line.

However, there was one super slow, relatively ridiculous, and extremely expensive project during the Cold War that has deliver a truly insane amount of returns and profit – the space race. The space race was really really expensive but the technology it produced we still use to this day. (This might be why idiot billionaires really want to go to space, but that is another discussion.) The point I want to make is that we need to start embracing slow scholarship because I believe that overtime the profits will be a lot better than a handful of dead links.

But I also know that slow scholarship costs money and people need money to eat so maybe this is not the perfect solution. What might work is intermittent scholarship. If we build systems of data storages, and networks that support intermittent scholarship we might be able to avoid “drive by collaborations” and “project websites”. The best option would be that we change the funding system, but that is very unlikely to happen so instead intermittent and slow scholarship systems might actually be our best bet. I imagine that these systems will support collaboration over longer periods of time and allow scholars to exchange “hunches” and thoughts more freely.

OHD_BLG_0060 Creative Tensions

From conflict to catalyst: using critical conflict as a creative device in design-led innovation practice

by Nathan Alexander STERLING, Mark BAILEY, Nick SPENCER, Kate LAMPITT ADEY, Emmanouil CHATZAKIS, Joshua HORNBY

I read this on Mark’s recommendation because I was talking about the workshops I wanted to run and how I wanted to set them up in a way that allow there to be tensions that can then be explore creatively. So reading this paper was probably a sensible thing to do.

Diversity?

The piece features a project that brought together a “diverse” group of people to think of ways to solve the wicked problem of cyber-crime under teenagers. The “diversity” of the group is not expanded on beyond that it was several people who either were doing or had done the MDI masters, police officers, and a couple of members of the public. This does not really explain the diversity to me. I want know where these people came from, how digitally literate are they, what ages are they? None of this information is enclosed which makes it hard for me to fully imagine the diversity. For all I know the diversity lies in the participants different heights.

We need to show this information because then I can truly see the diversity rather then relying on people word, which is really hard since the idea of diversity is subjective and it is a word that is very much thrown about.

Get out of my shoes

The paper talks a lot about “deep empathy” which when I first learnt about it during my masters I was on board with, now I very much reject this idea. Why the sudden change of heart? Well, for me it started to become clear that terms like “deep empathy” is a gimmicky way to show the performance of diversity. Instead of actually employing a diverse group of people we bring diversity in for a workshop, get them to do a couple of exercises and then send them on their merry way. The paper does note that some participants thought that you could not really get a in depth and nuanced idea of someone’s point of view because of the time limit and the group setting.

I personally think that telling ourselves that we can fully understand where people are coming from in a short space of time is delusional and reductive. If I am being completely honest I do not think I will ever be able to understand the experience of a black man. A white man? Maybe. But only because of the cultural domination of white men. But a black man? No way. A person in a wheelchair? Nope. A transgender person? No. It is not because I do not try, but because I believe that one cannot communicate a human life through words alone.

“Deep empathy”, “active listening” etc. these can all work in an attempt to understand people, but we should not deluded ourselves that we can embody another person’s life experience. I think it’s really necessary to put an intersectional feminist lens over this, because it is a dangerous path to go down.

The DaDa way

Now here is something fun. The participants thought that by blowing up the creative tensions and making them very obvious people could better understand them and use them. They also wanted the view points to be a bit more than a line of text (news flash you cannot judge someone by their tweet). People wanted images, videos, animations. These were things they felt they could relate to better. This got me thinking about a discussion I had with Joe about a podcast, the Bodega Boys. The podcast is super strange to listen to but because everything is very absurd they can tackle difficult issue. In this podcast they create this strange but safe space. The absurdity makes the issues more approachable and digestible. This then got me thinking about DaDa and how they came to be in a time of a nonsensical war. We are kind of in a nonsensical time now, maybe we need Dada to create empathy.

OHD_BLG_0062 Create a bit

Summary of the Createathon 19/04/21 – 23/04/21

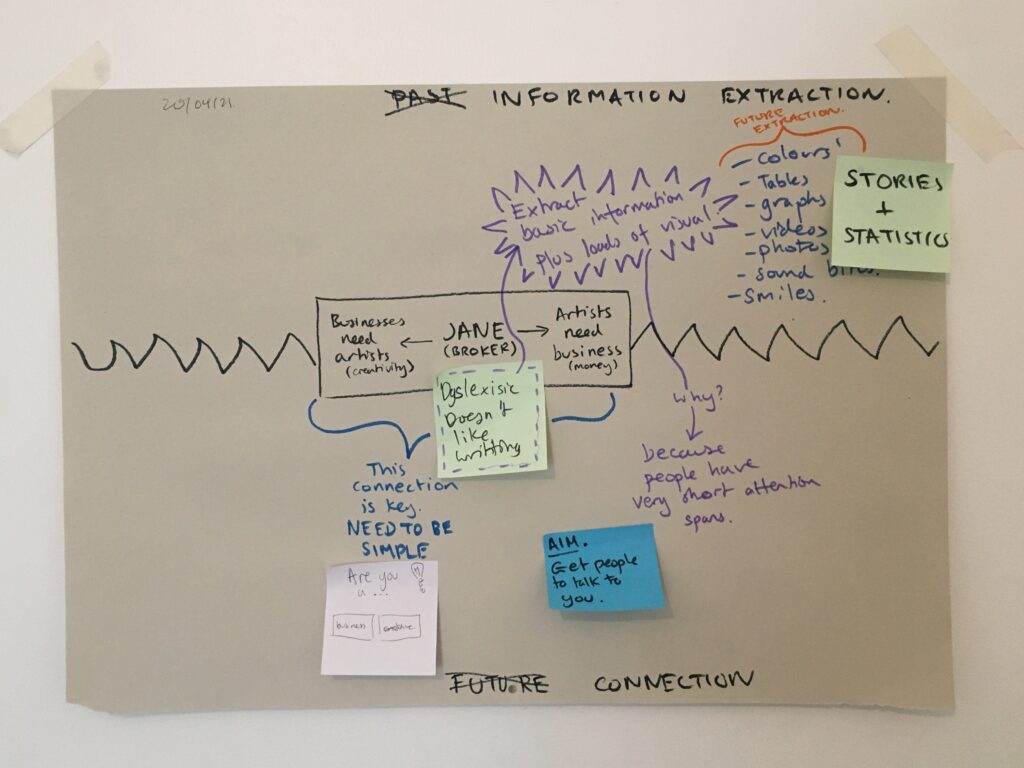

I took part in a Createathon because it has been a while since I had done a design workshop and I wondered if I could still do it.

During the first day of the workshop I started to remember some of the painful aspect of doing design workshops. For example the time limit, in my opinion, dulls the creative process a bit, so you start thinking of easy wins instead of bigger pictures. There is was also a lot of rambling talking which was a little frustrating.

However…

In the end my group, which was a girl from Azerbaijan and a PhD student who had also work with Seaton Delaval Hall, delivered a pretty good presentation and we didn’t mention social media once! We had not really come up with super great ideas, instead we had kept it pretty open ended and offered the person whose business we were working with only a vague direction for the future. I personally thought that it wasn’t going to go down well but it really did. After we had explained the plans of actions and presented our Pecha Kucha, the client was super enthusiastic, because she suddenly saw her business in a different light. We told her her story but how we understood it and this process of multiple translations help her get an inspirational boost.

What I took away from the Createathon is that what I really want to do as a designer is not give someone a stack of clear cut ideas but a new way of thinking. I want this because that is far more sustainable in the long run and it is also harder to dismiss. You can throw away a stack of ideas but if I have incepted a new way of seeing the world into your brain that is hard to ignore.

OHD_BLG_0063 A Spanner, a Chat and a Gang

Subheading: a meeting with Lucy Porten

Bad news first? Or good news first? Lets end on a positive…

The Spanner

So… The National Trust is not an archive. Every recording is stored at the British Library and you have to pay to get it out; a small fee but still. A fabulous perk of having it stored at the British Library is that the library is a power house and has the money and facilities to keep everything updated and playable. They also have great paperwork, which can be interpreted in multiple ways. The National Trust also does not use this archive. The National Trust podcasters have only recently discovered the existence of the archive, which is a bit awkward. Also it is unknown whether the British Library wants to store any edited recordings.

This does not mean that I am not allowed to keep copies of the recordings at the hall, but the British Library have pretty strict rules around keeping second copies. They are definitely a bigger stakeholder then I initial imagine, but I think we can still think of something.

Added note (27/04/21) Tried to find the National Trust archive on the British Library website and failed. Even asked the help chat and they could not help me.

The Chat

I mentioned that I was interested in doing an oral project around this oral history project, Lucy reacted by saying that she also was interested in doing an oral history project of oral history at the National Trust. The National Trust seems to be in a similar spot as the UN and the WTO where they have no idea how they got where they are now.

The Gang

Now this is the really fun bit because Lucy’s and my thinking do align, and my CDA is starting at a time of change within the National Trust and an increasing interest in oral history. Lucy therefore wants to set up an informal gang of like minded people and I have an invite. Hopefully this will result in a super helpful network of people who want to reform how oral history is conducted at the National Trust with an extra focus on reuse. Yay! I have also offered my services as someone who can deliver all sorts of fun innovation workshops.

OHD_BLG_0065 New words among other things

Readings:

Community archives and the health of the internet by Andrew Prescott

Steering Clear of the Rocks: A Look at the Current State of Oral History Ethics in the Digital Age by Mary Larson

Sometimes I feel like we are in the trenches with our machine guns and old military tactics…

This ain’t for you

People live their lives in very specific ways. They have certain rituals and values that they hold very close to their hearts. However it is very unlikely that everyone else in the world has the same approach to life as you do. Some people do not use the right tea towel in my opinion, some people think it is perfectly fine to wear socks in sandals, and some people a zero problems with eating meat everyday. In the case of Prescott’s paper on community archives/Facebook groups we have an academic freaking out because a community is not archiving properly something which he considers to be a great sin, and yes, in a certain way it is a great shame that a community archive is not sustainable because of the platform used or the limited funding. This is especially the case when you come from an oral history angle where one really wants to preserve the voices of those who current fall outside of history. However, maybe we need to remove the academic lens in these situations, maybe these archives just aren’t for you. They have a different, more temporary, function to bring people together over a shared history. They are about sharing history not preserving history like archives do.

This is where I think I (as an academic 🤢) feel that my role is not to impose my beliefs onto these make-do archives but instead build better tools to support them. A community archive on Facebook is a different beast to the university backed oral history project. Truly it is a shame that this knowledge might go missing, but then I suggest that we get more minorities to work in academia rather than dictate what we think they should do.

It’s a power thing.

Anonymity is anti-oral history ?

…, anonymity is antithetical to the goals of oral history if there are no exacerbating risk factors.

Mary Larson

Anonymity, accountability, freedom of speech, privacy, welcome to the 21st century. There is the opinion within the field of oral history that anonymity is against the principles of oral history. This is mostly because oral history demands a high level of context in its reuse, which makes complete sense. However does that mean that all information should be available? Is it impossible to have different levels of anonymity?

It seems odd that currently when it comes to privacy we have to work in such absolutes. You can get a certain level of privacy on the internet but that often requires lots of digging around and downloading plugins that send out white noise. You basically have to spend time fending off those who run the platforms you use, which when put in a AFK context would be the equivalent of the shop keeper pickpocketing you while you were shopping. Currently privacy and anonymity equals not using either the internet or archives, which defeats the point.

Why is this our only option?

Well, in my opinion it is not. We just need to get a bit more creative for example:

- Use pseudonyms

- Use other identifiers e.g. White, young adult, middle class, female (that’s me)

- Use identifiers + 𝓲𝓶𝓪𝓰𝓲𝓷𝓪𝓽𝓲𝓸𝓷. There are loads of researchers who have to use their imagination because history has not been good at recording their subject

- Only allow access to certain information if you either visit the BAM archive or ask for permission

- Generally encourage more thorough and ethical reuse and research

New words

To elaborate on that last point we currently approach the ethics around archiving from the donating angle; if everything is correctly archived now there will definitely be no more problems in the future. This attitude I do not find very sustainable because attitudes towards ethics change all the time. So instead I purpose a different angle: ethical reuse of archival material lies predominantly with the reuser not the donator. This is where I would also like to insert the ‘new’ words. Instead of using the terms ethical and ethics we instead use responsibility and care, because the former is so slippery so ‘high-level’ thinking that it loses its meaning while the latter are more human words. Responsibility and care are concepts that you teach your children. They are more instinctive. So what I wish for is more care and responsibility from those who reuse oral histories. I want the reuser to remember the human-ness of the archive and the responsibility they have to care for their other humans.

NOTE: this is why I love the idea of archival ghosts so much because it gives the oral histories a face.