So today im going to talk about designing in GLAM, by telling you about my experience designing in the national trust. Which I have illustrated with this can of treacle. And this is because one of my national trust supervisors described trying to basically get anything done in the trust as swimming through treacle. And it feels like it encapsulates my experience of designing in the trust.

//

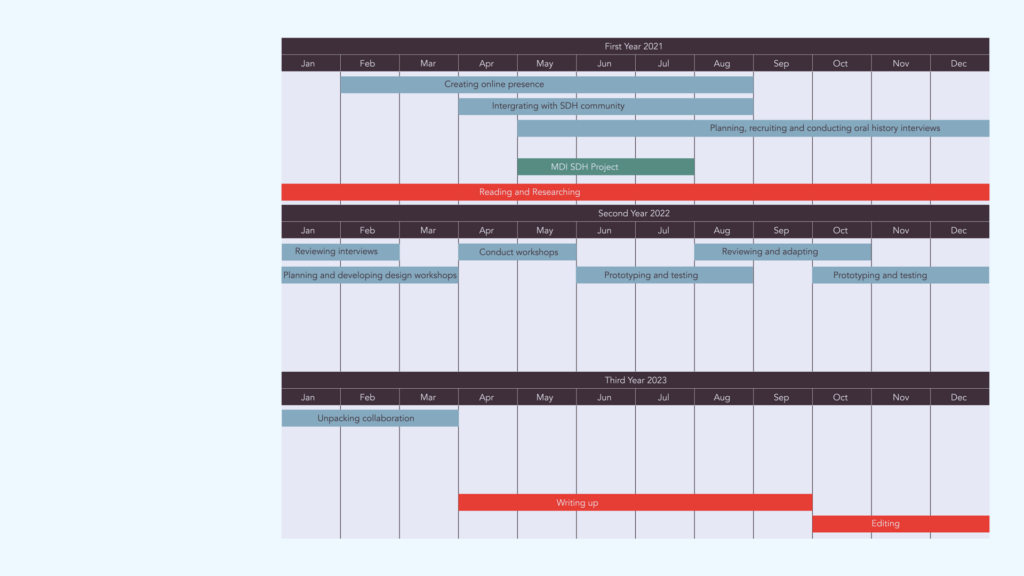

To give you an idea of what I mean. I’ll show you my initial project plan I made right at the beginning of my phd.

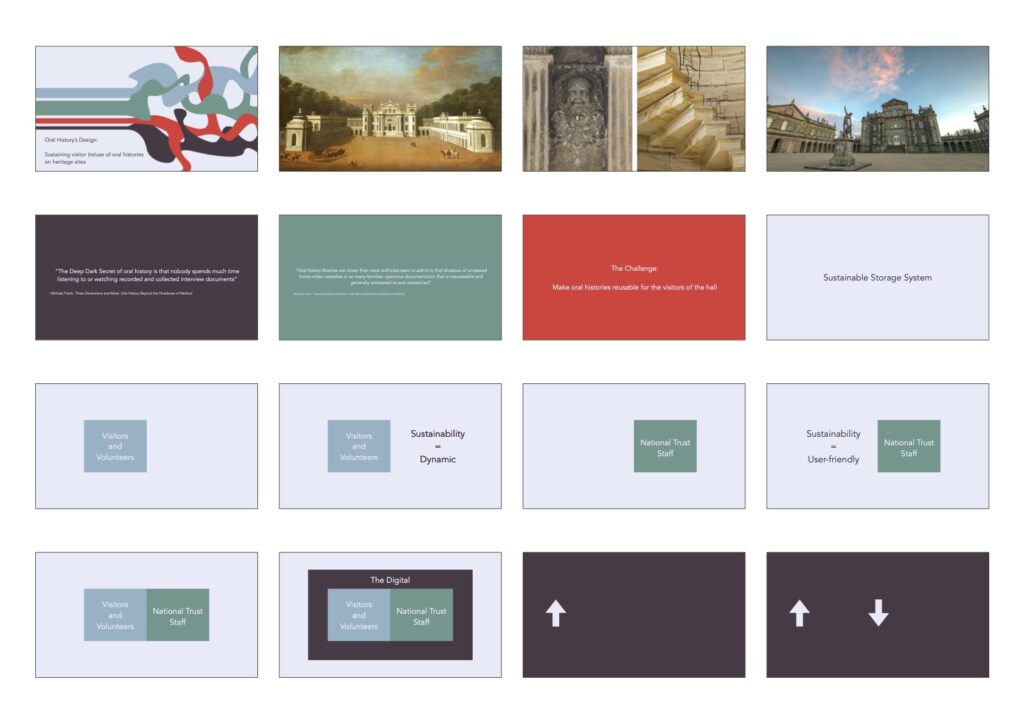

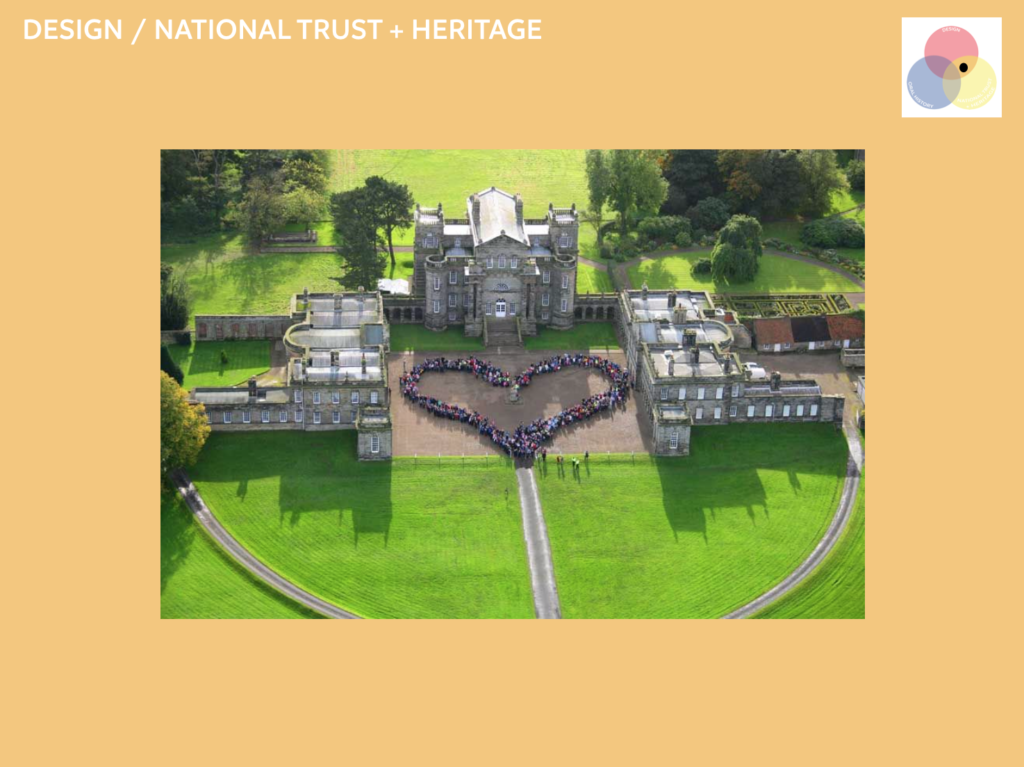

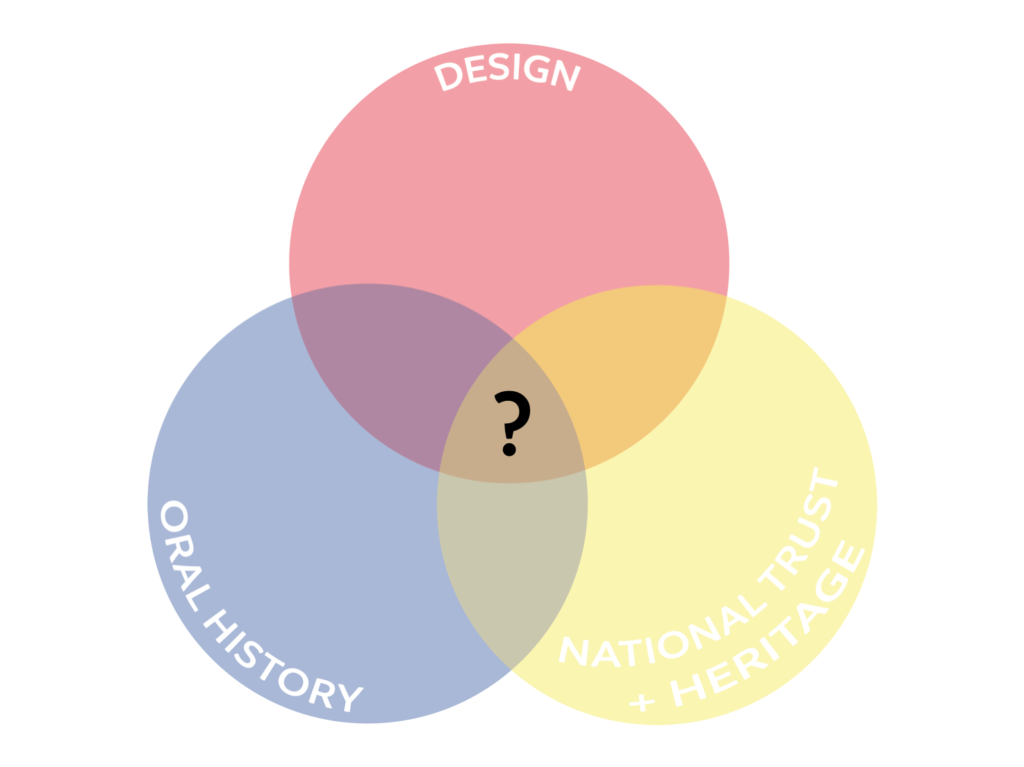

So quick bit of CONTEXT my phd was developed off the back of the final project I did for my masters in multidisciplinary innovation. The task for the project was create an oral history project at Seaton Delaval hall and one of our conclusions was this archiving of oral history thing, you could make a phd out of it. And so we did. And I was going to look at creating something that specifically allow visitors to reuse oral histories on heritage sites. So in my mind this was likely to be some kind of sexy software that would just be so sleek and amazing that all oral histories problems would be solved. And this was my original plan on how I was going to do this is this. Now pretty much everything about this is wrong. Firstly because it is three years instead of four years, it does not include any of the placements I did. But also the entire process just did not or could not happen.

[UNPACK PROJECT PLAN]

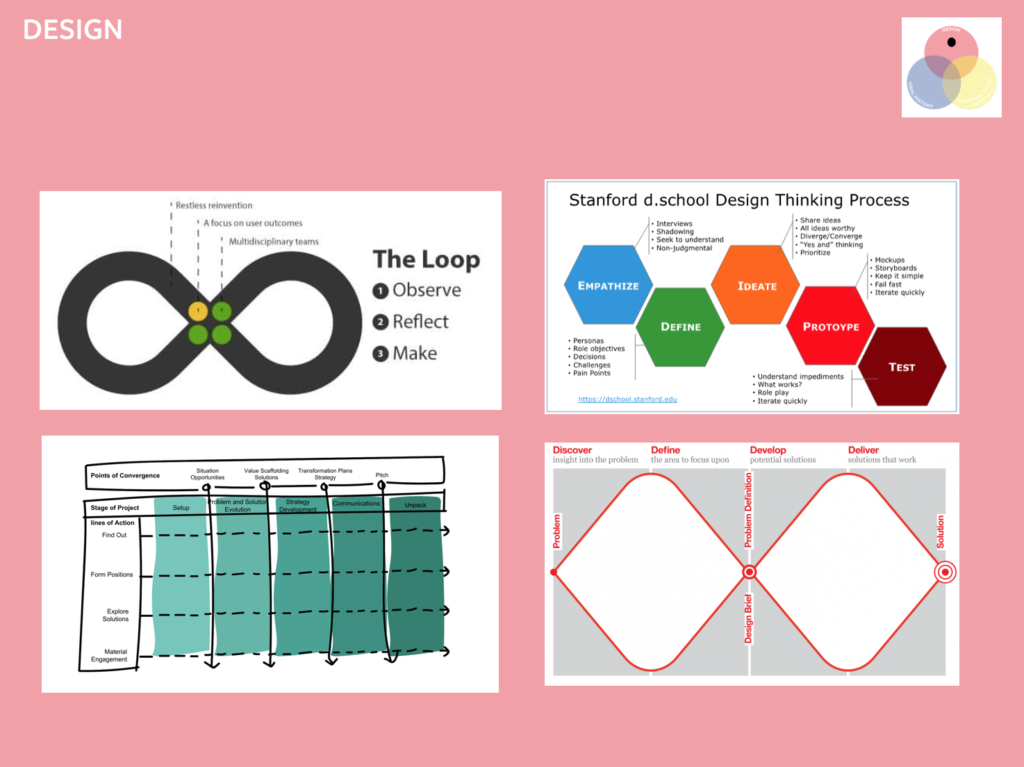

I did realise that the usual iterative testing process is just not really possible because but I could never properly test them.

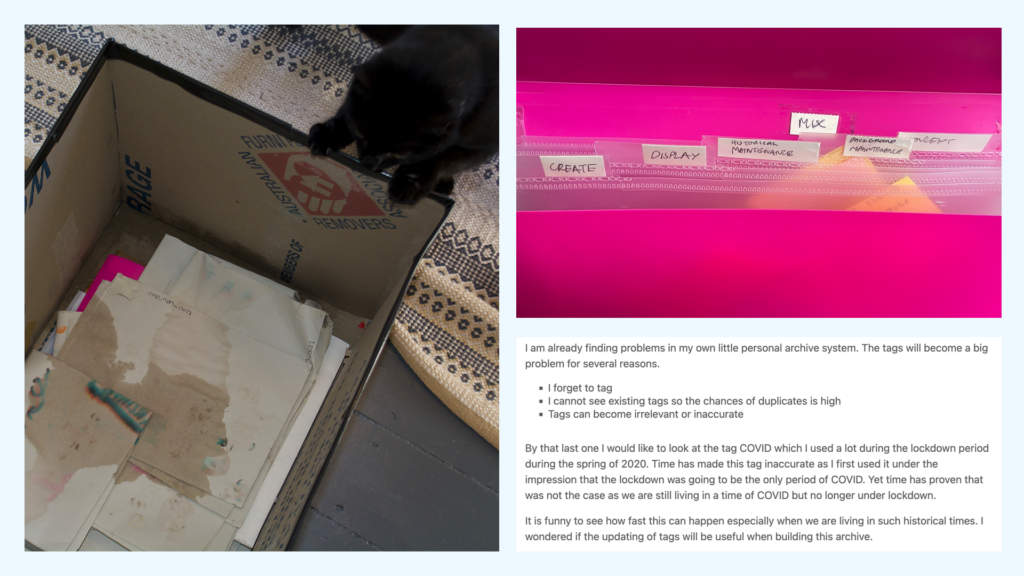

The only example I can give of iterative testing is with my own archive. But this has nothing to do with the working with GLAM bit.

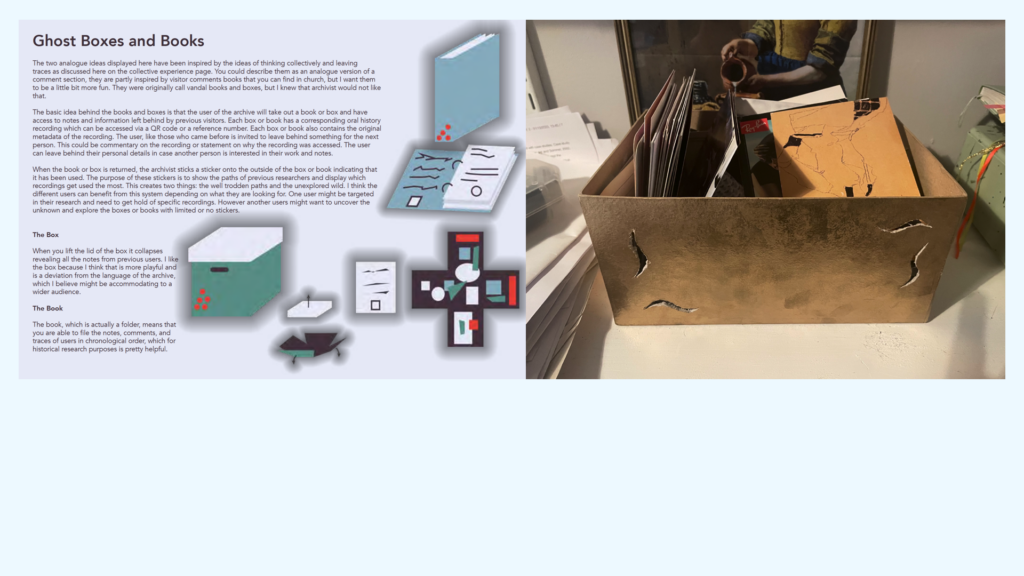

I did give prototyping a try and although I did not test them.

However I thought the lack of testing told me a lot about the design environment.

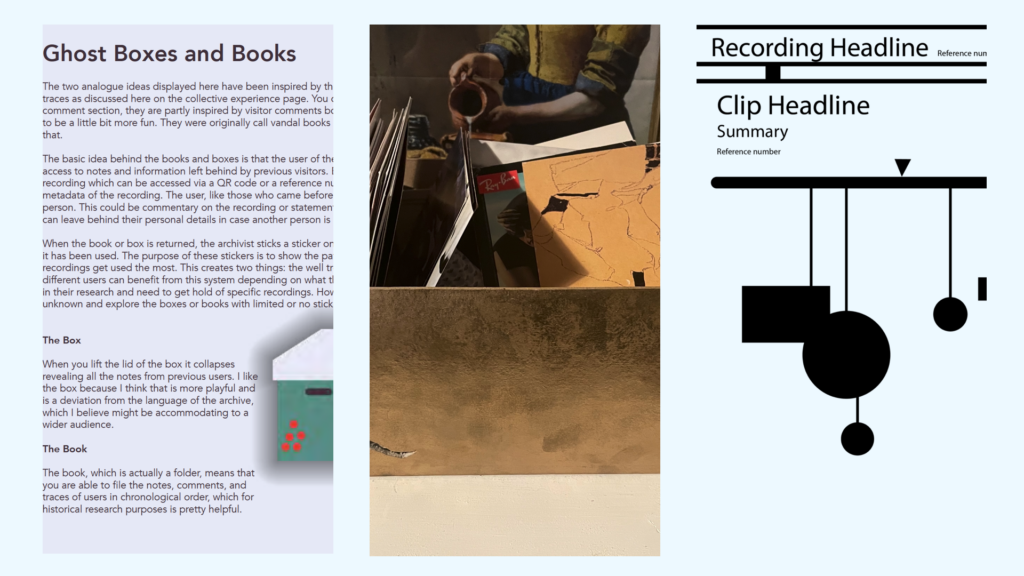

I could not test the ghost boxes because they did not know what material to give me to test this with nor did they have the space for it, and most importantly they did not want to make any promises. The sound box could not be tested bc you are not allowed to have external tech in Nt and what oral history was I going to possibly use. The transcription ribbon was also one that could not tested because what laptop would that work on. So the lack of testing was not a complete failure in the end.

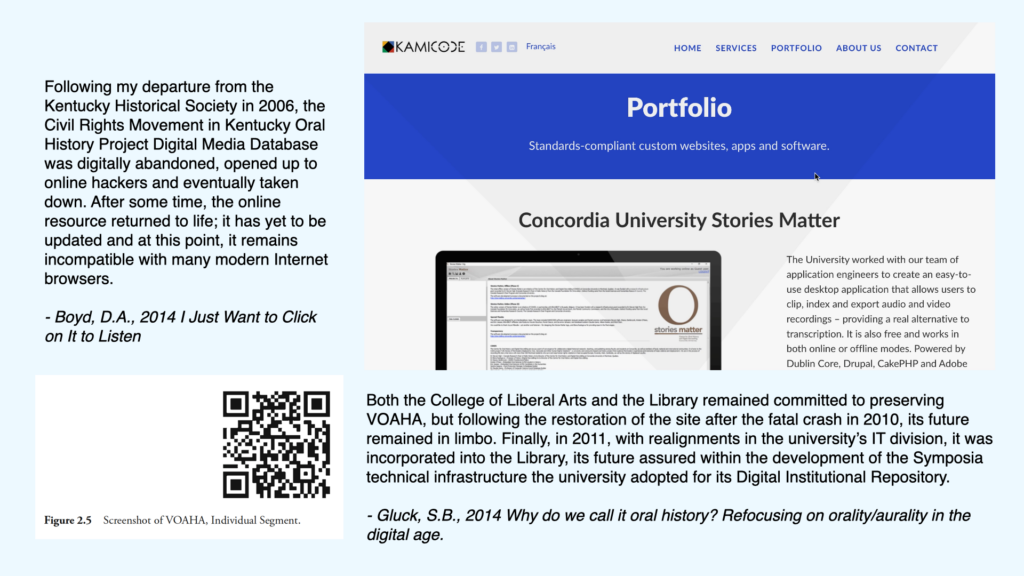

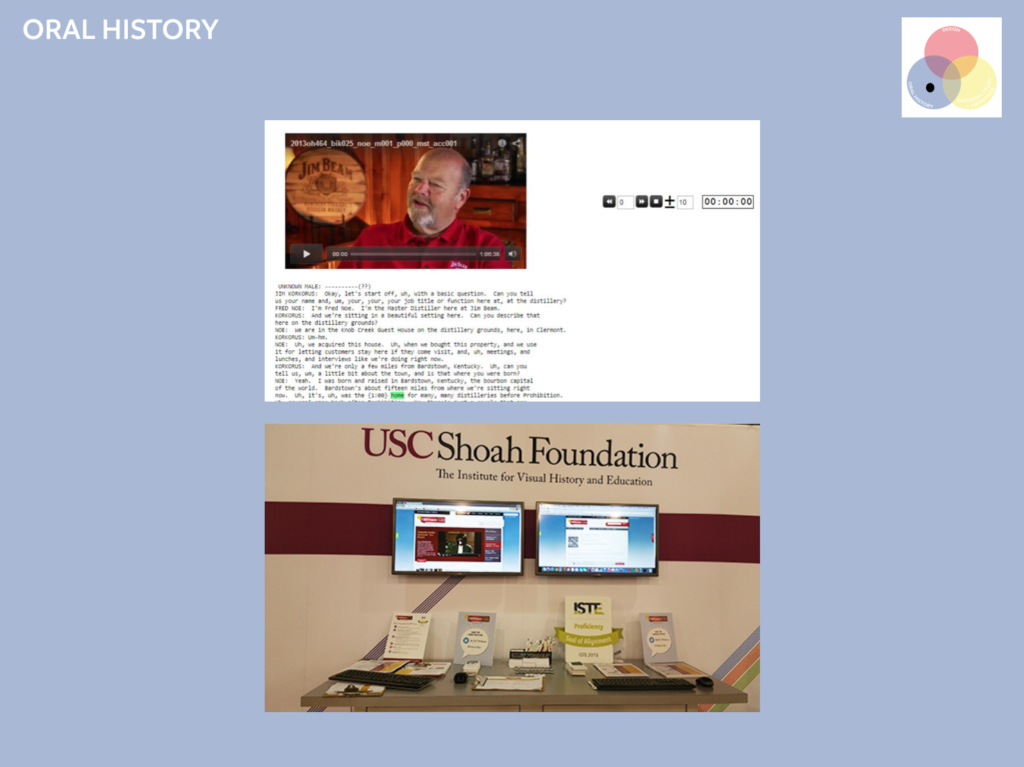

But I still need a new approach which I found after I looked at previous attempts at making oral histories more reusable. There have been a collection of attempts to make oral history more reusable. And most of them have failed ish. It is weirdly hard to do research into this because people did not really write a lot about when things failed. They publish papers on the super new tech and then they just disappear. Luckily there is one book that does talk about some failures. Boyd quote, VOAHA and stories matter

These all failed because people did not think about the maintenance of the work. And if we look at my prototypes you see the same issue. What these prototypes told me and the various attempts at making oral history more reusable. Was that it is not about what you make but about how you maintain it.

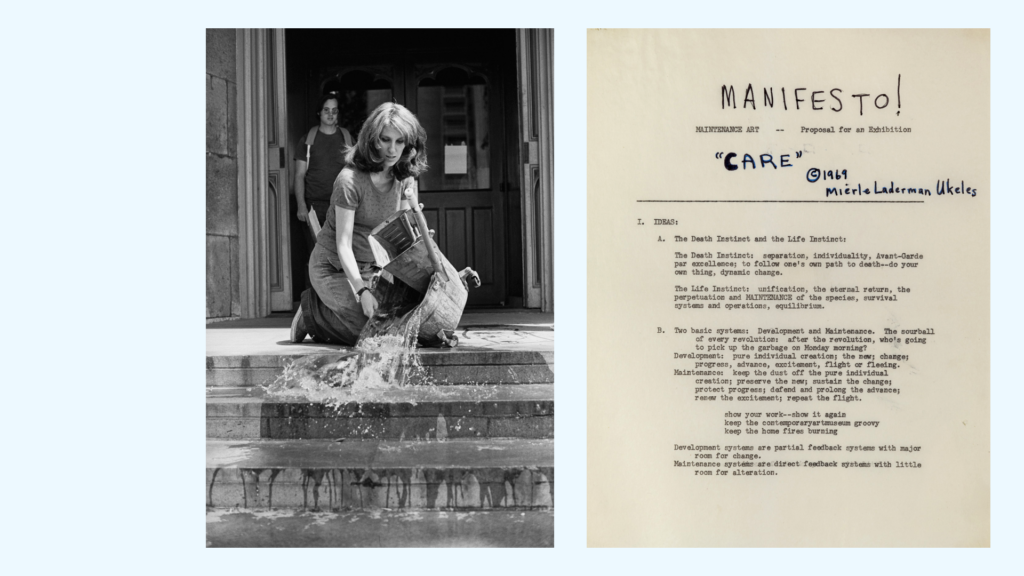

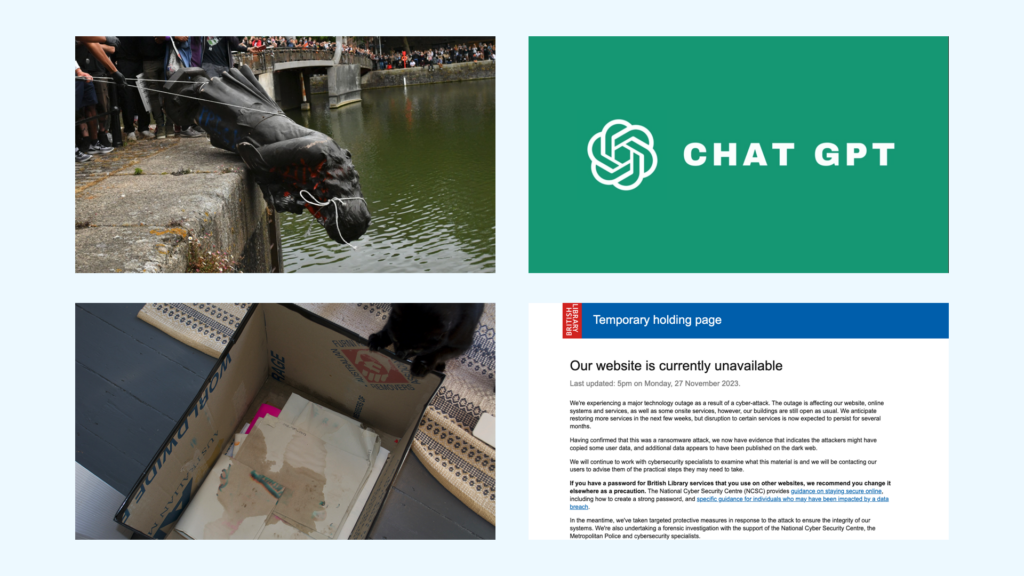

Which is how I get to Mierle Laderman Ukeles. Is a maintenance artist. She wrote a manifesto for maintenance art. Where she wrote the line “after the revolution who’s going to pick up the garbage Monday morning? I remember seeing her work during my time in art school and absolutely loving at the time but I had forgotten about it until it was mentioned by The British Library oral history archivist Charlie Morgan, who used this quote in a blog post about all the recordings that were made during the pandemic and how someone is going to have to archive these someone is going to have the clean up after the revolution.

So from this I wrote a manifesto for maintenance design, which I had totally forgotten I had written. So ukeles spilts the world into two systems in her manifesto the development system and the maintenance system, which she labels the death instinct and the life instinct. In terms of maintenance design I have put under the death instinct is that this is about drive by collaboration and the life instinct is simply life goes on. The designer is only a visitor to this space.

– labour

– limited resources (which also basically include labour. And I. Think that is also why I connected it to earth maintenance and looking after the planet)

So I decided to work through the lens of maintenance. but maintenance as a thing is really annoying because it is really hard to see if you are not part of it. IF you look t people who write about maintenance or infrastructure like Susan Leigh star a recurring theme is that you cannot see the value of maintenance until it breaks down. So my idea was that I would probably have to get very close to the situation in order to try and understand and map out the maintenance in these heritage sites, archives and look at how oral history needs to be maintained.

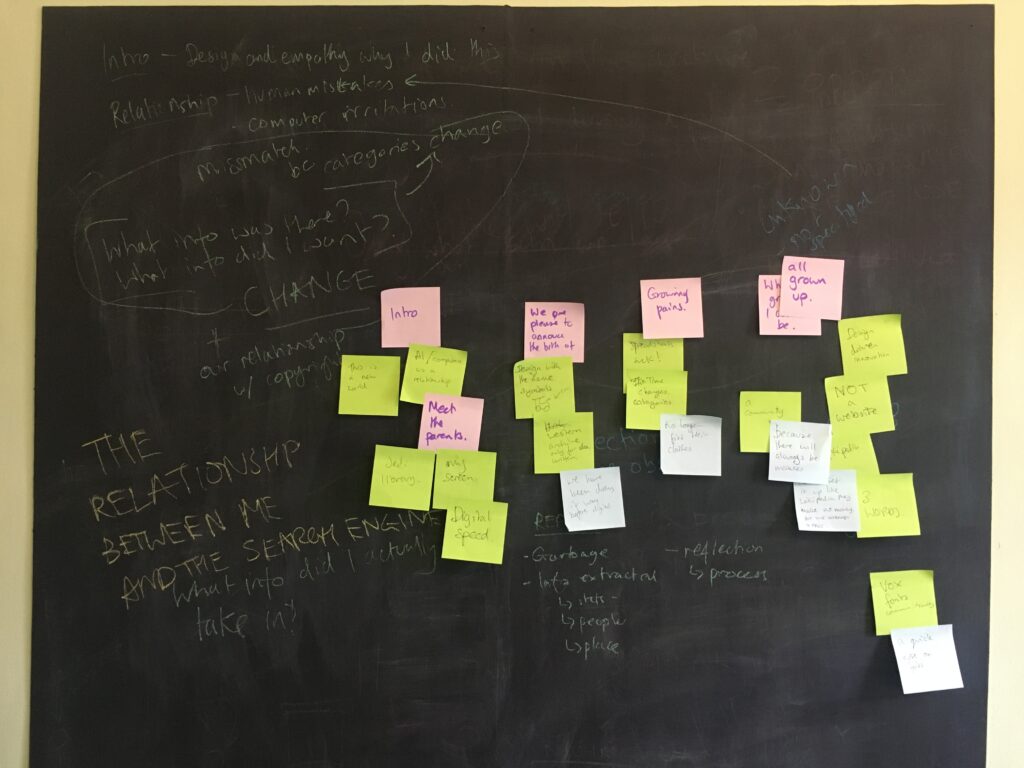

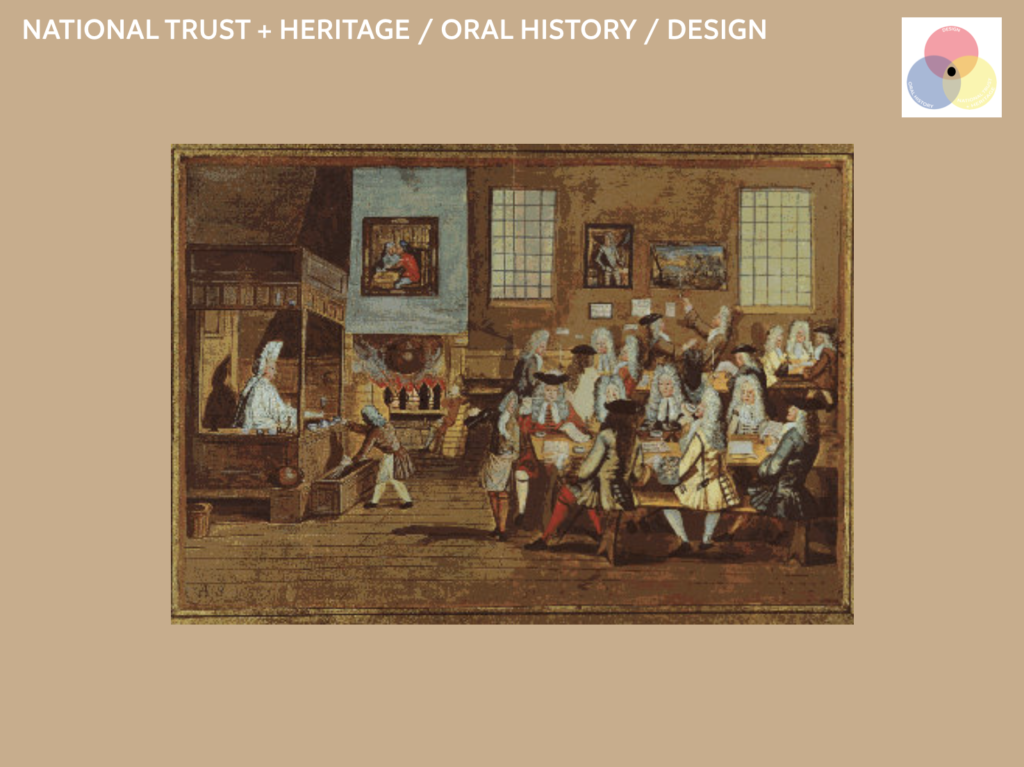

And this is how we get to Action research as a design strategy but while action research is normally the researcher going in and working with the stakeholders, but really what I did was work for the stakeholders. I literally went in and was like what do you want me to do. I have these skills how would like to use them. And so they would give me a task to do and then I would bring it back to them for feedback and they would yes no no no no yes maybe, not yet. In the reflective practitioner Schon compares being a reflective practitioner to what jazz musicians do, as they make it up and go with the flow. And that is very much what I had to do because no one tells what you need to know, either because they do not know or more often they simply do not have the time. I could have rocked up with my cute little sound box, they could not care less. They are thinking about the car park and whether the cafe has enough stock. You know how I found out the issues of IT at the national trust, my lovely supervisor was like you are tech could you sort this out and it was a nightmare. I then told the IT guy and he was like I’m gong to pretend I did not here you say that. You have to think on your feet the entire time and by working with or for them you can start building a better idea of the space you are designing in.

So action research was my strategy and under that came all these different case studies I was able bc my funding body is like go do placements. So what did I actually learn on these placements, well firstly my phd was going to be super unsexy.

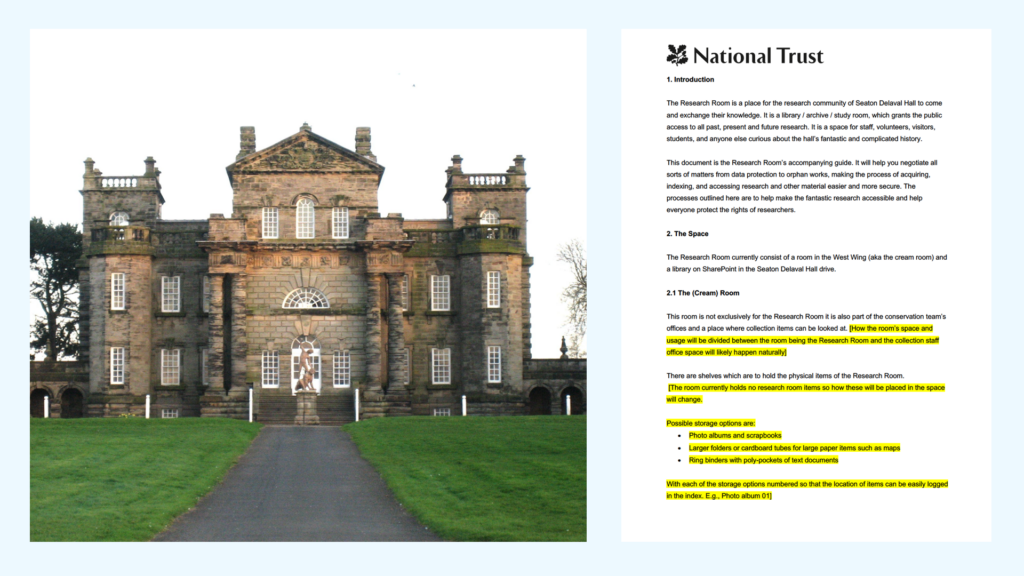

– Seaton Delaval Hall:

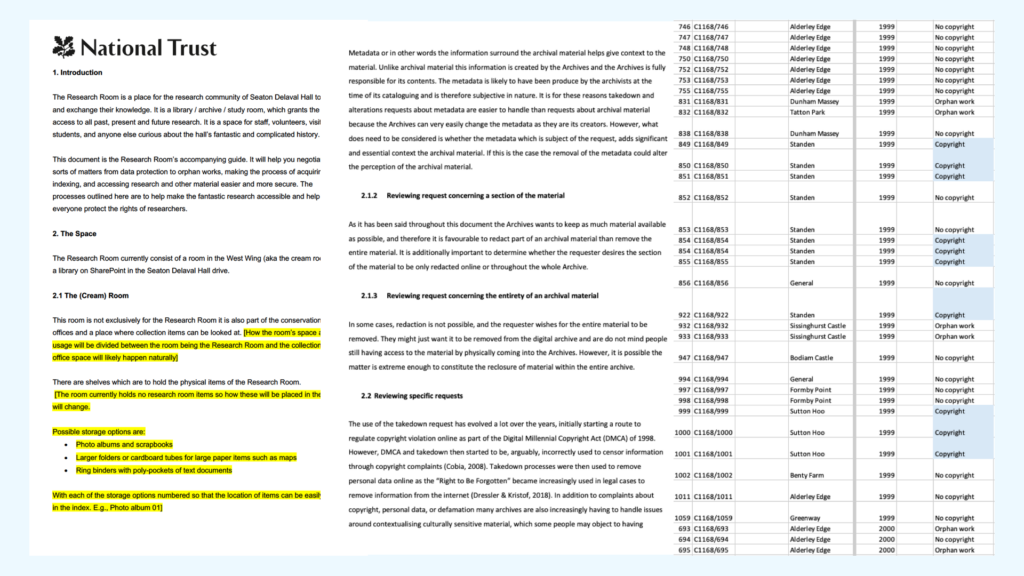

research room design:

leaving room for change:

working with maintenance, leaving room for the stakeholders to make their own changes. It is about setting up a framework.

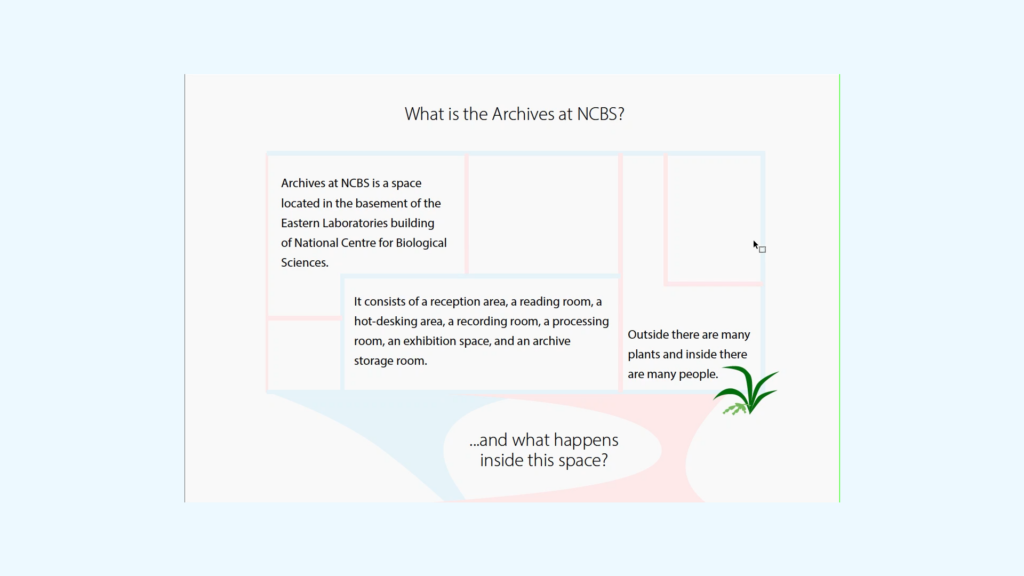

– NCBS: policy development: takedown policy and sensitivity check doc: have to really thorough think about what we mean by archiving: understand what GLAM does

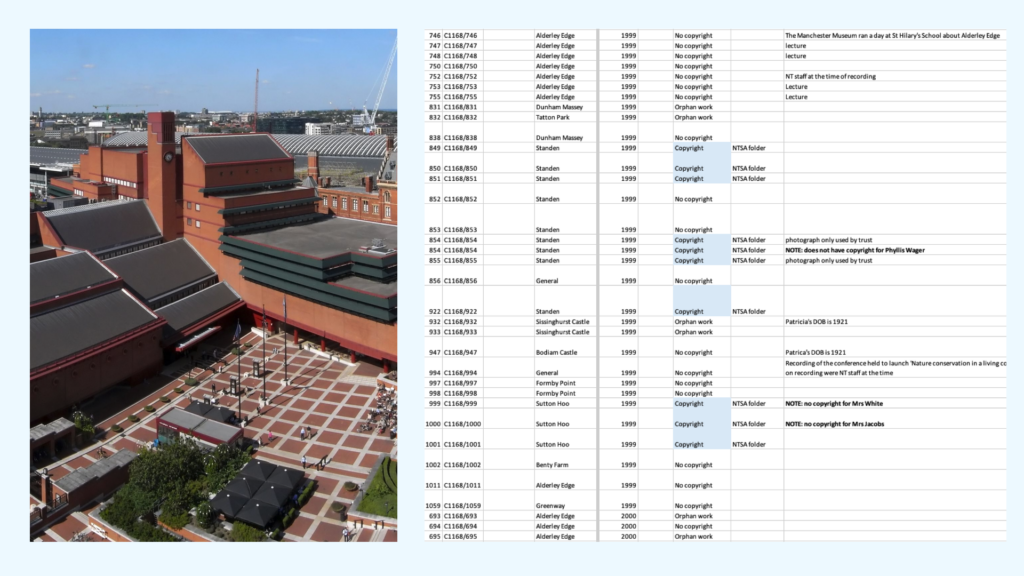

– bl: audits: what can history tell us: working with change

So I learnt some good things while on these placements

– working with maintenance is allowing room for the existing structure to absorb your work by offering a framework not dictating a single solution.

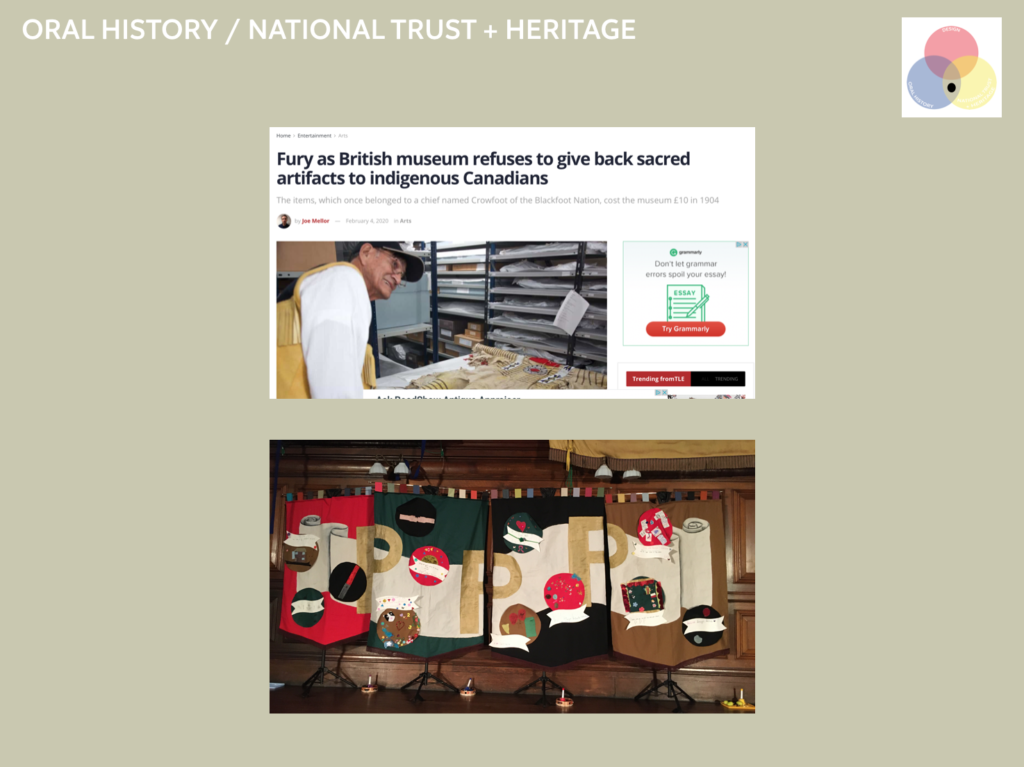

– what GLAM does. It collects people’s property and thats complicated

– things changes and this effects how we maintain. So although I am focused on maintenance I also recognise that maintenance has to move with the times otherwise it breakdowns down and we working to restore not maintain.

But what do I say if someone comes up to me and is like “how do I design in GLAM?” How do I swim through the treacle?

Well I can tell you what GLAM does.

1. It collects peoples stuff. It collects people’s property. It might be something they own or something they made. and there are laws, ethics, and cultural customs that are around this you cannot forget. Also they might change and vary between countries.

It does two things with this stuff. It keep it and it curates it. how long something is kept can vary from whenever an exhibition is finished to forever either way however long it is kept it must be maintain and safe. How it curates it is also deeply political and never truly objective.

So if this is the why and what. The how is creating the balance between creation/collection/development and maintenance. Or more simply said Change and stability.

First It is about spreading the resources you have other these two spaces. NCBS

And the second is to one big ol’ theory of change or risk assessment.