Chpt. 01 – The History of Oral History Technology

“The history of progress is littered with experimental failures.”

– Victor Papanek, Design for the Real World

Let is take a moment to contemplate the MiniDisc. Developed by Sony in 1992, it was meant to replace the cassette, with its ability to edit and rewrite recordings, and 60 – 80 minutes audio storage, it was the hot new thing that was going to change how we record forever. Fast forward thirty years or so and the MiniDisc has become one of the textbook examples of a failed technology. For oral historians and sound archivists the promises made by the Minidisc were never fulfilled but for different reasons. For oral historians it was difficult to use when recording, and for sound archivists it was incompatible with certain editing and storage softwares, and sharing files was not universally possible (Perks, 2012). Today there still is a disconnect between what oral historians want from technology, what sound archivists want from technology, and what the technology actually offers. It is a three-way relationship where no one is completely satisfied. Oral historians wish technology to provide them with the tools to better contextualise their archived oral history recordings and utilise the orality of oral history recordings, even though oral historians have heavily relied on transcripts for years (Boyd, 2014; Frisch 2008). Archivists simply want a technology that will last and ensure access for many, many years to come (Perks, 2012). Technology however does not exclusively cater to oral historians and sound archivists, but supplies far more lucrative fields and is therefore more likely to bend to their needs and desires (Perks, 2012). This means there is a gap in the market for technology that satisfies oral historians and archivists. Over the years there have been several attempts to fill this gap. I say attempts because no one technology has completely fulfilled oral historians and sound archivists wishes, some are very close but complete adoption has not yet been achieved. To some extend this is due to people having their fingers burnt too many times, I refer back to the Minidisc. Alongside the differing needs of oral historians and archivists, there is the tension between the techno-enthusiasts and the techno-phobes. While some oral historians, like Michael Frisch greet the technological age with much enthusiasm others, like Al Thomson have taken a slightly more cautious approach (Frisch, 2008; Lambert and Frisch, 2013; Thomson, 2007). Although truth be told it is difficult to constantly be aware of people’s feelings towards technology as it is so rapidly evolving. When Al Thompson wrote about about the digital revolution in Four Paradigm Transformations in Oral History, Youtube was only two years old and social media sites were not as prominent as they are now. Rob Perks wrote Messiah with the Microphone before the huge revelations around the NSA and GCHQ surveillance in 2013 and the Cambridge Analytica scandal post-2016. Not to mention the colossal impact the COVID-19 pandemic had on both the fields of oral history and archiving and their relationship with technology.

Nevertheless, taking all of this in my stride, in this chapter I wish to explore the attempts made to find a technological solution to the problem of archived oral history recordings as my project makes up part of this bumpy ride. I wish to take a moment to reflect on the history of oral history technology, investigating what has happen so far and what I can learn from my predecessors. Above all what I am looking at is why they failed. At face valued this seems cruel but in reality any story about innovation is a story about failure (Syed, 2020, p.43; Papanek, 200, p. 184). The trick is to look failure in the face, something designers are repeated credited being good at (Syed, 2020; Kelly and Kelly, 2013). So that is what I am going to do. I, a designer, am going to visit my ancestors, the endeavours that sadly failed, and my elders, those who are still battling away. I shall pay my respect, listen to their stories and warnings, and build the foundation of this project. My journey starts with a visit to the graveyard of oral history technology.

Welcome to the graveyard

The oldest plot in the graveyard of oral history technology belongs the TAPE system. A system devised by Dale Treleven in 1981 at the Wisconsin State Historical Society, that encouraged users to access oral history tapes in a way that puts ‘orality’ at its centre. Naturally it was deemed to much and not shiny enough (Boyd, 2014). The second oldest and rather grander plot belongs to Project Jukebox. Developed at the University of Alaska Fairbanks at the start of the nineties it was described as “a fantastic jump into space age technology” (Lake, 1991, p. 30). However according to Willam Schneider, one of the developers, it was more like a “stumble” into digital technology with the naive hope that it would save time and money (Schneider, 2014). There is mention of CDs, dial-up technology, and software support provided by a corporation they refer to as Apple Computers Inc. (Lake, 1991; Smith, 1991). Project Jukebox did not fully make it out of the twentieth century, but it definitely started trend. Next to Project Jukebox lies the grave of the Visual Oral/Aural History Archive or VOAHA. Sherna Berger Gluck at California State University, Long Beach was deeply inspired by Project Jukebox during the creation of VOAHA, specifically their approach to ethical concerns surrounding sharing oral history recordings and its ‘boutique’ nature (Gluck, 2014; Boyd, 2014). Although this time there was a focus on ensuring that it was better connected to the web, we were after all at the turn of the millennium and the internet was getting big. Eventually both Project Jukebox and VOAHA became victims of the seemingly inevitable technological advancements and university budget cuts, however both are also survived by their ‘children’. The former has a version available online and the latter was absorbed into the university library system, not without some hiccups (Gluck, 2014).

Beside these two juggernauts of projects the graveyard is filled with similar endeavours, mostly websites copying the ‘boutique’ style interface, which remained largely the same only slight altering to fit wider developments in digital aesthetics (Boyd, 2014). An example of such website was the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database developed by Doug Boyd, which in his words was a “gorgeous” website that had “logical” information architecture. However, the requirements to achieve this ‘boutique’ style every time a new recording was added were too high for these larger scale oral history projects, making ventures like Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database, Project Jukebox and VOAHA, more akin to well curated exhibitions than oral history archives (Boyd, 2014, p. 89). Another project, Montreal Life Stories, established at Concordia University seemed to whole heartedly embrace this digital exhibition format. Steven High writes how digital storytelling, using digital software to blend together various mediums into a narrative experience for a viewer, became key in ensuring better community participation in the Life Stories project (High, 2010). Sadly, although no surprising, www.lifestoriesmontreal.ca no longer links to the original project. When reflecting on Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database Boyd admits this focus on the userbility led to a lack of consideration for the maintenance required to keep his website running. In the end it was “digitally abandoned, opened up to online hackers and eventually taken down” (2014, p. 9). Just like Project Jukebox and VOAHA, the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database is survived by a comparable version on the web today. I am of course unable to compare the two, however the project’s kin does seem to crudely jump between host websites and insist on opening a new tab every time. Nevertheless the same cannot be said for many of the project’s comrades which leave nothing behind bar a trail of dead links.

In another part of the graveyard lies the significantly smaller section of oral history software. Here Interclipper and Stories Matter lie side by side. Interclipper was a software most prominently championed by Michael Frisch, who in 1998 saw the market research software as the answer oral history’s archiving problem. The appeal of the software was its ability to ‘clip’ larger audio files to into more bitesize chucks and adding appropriate metadata (Lambert and Frisch, 2013; High, 2010). Sherna Berger Gluck decided to use it in her pilot project pre-VOAHA, however Gluck opted to develop her own system instead as Interclipper did not supply a digital file of the entire oral history recording alongside the clips, and its database was not compatible with the internet (Gluck, 2014). In another situation, students at Concordia University tested out the software and found it frustrating to use, worried about certain information being lost, and thought it too expensive (Jessee, Zambrzycki, and High, 2011; High, 2010). This testing was part of a wider project for developing a new oral history software, which would become Stories Matters.

Stories Matter started as an in-house database software created at the Centre of Oral History and Digital Storytelling at Concordia University. It was meant to be a software for oral historians by oral historians (High, 2010). Like all its predecessors, including TAPE to some extend, Stories Matters wanted to move away from the transcript and focus more on the orality of oral history recordings, and better contextualise the recordings. Jacques Langlois from Kamicode software was hired as the software engineer. He mostly had experience developing video games and no experience with oral history (Jessee, Zembrycki, High, 2011, p. 5). From the article written about the project the development process seemed to be a bit of a bumpy ride filled with miscommunication and endless bug fixing, in other words a classic design process. And yet as far as I can tell Stories Matter no longer exists. The majority of the links in the article on the software are dead and, although Stories Matter does have a page on the Kamicode software website, I am unable to download it.

Neither Interclipper nor Stories Matters are available to use, hence the graves. They, like the digital archives/exhibits, broke down under technological advancements, university austerity, and a lack of maintenance, leaving nothing but suggestions of their existence in a handful of papers. In a relatively short period of time this graveyard has been fill with projects initial fuelled by the promise of technology advancements only for them to left in the dust. At first this all seems to be a deeply tragic story but then I must remind you of the quote at the start of this chapter: “The history of progress is littered with experimental failures” (Papanek, 2020). So let us see what we able to learn to from all these failures.

Learning from my ancestors

After visiting my ancestors, walking between all these graves, there is a lot to unpack, but one thing stuck in my head, Doug Boyd’s story of the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database. The database was, according to Boyd, a beautiful site to behold, yet fundamental requirements were not met and it stop working. This reminded me of the age old debate between whether a design should be functional or beautiful. In his book, Design for the Real World, Victor Papanek writes how the most asked question by design students is “should I design it to be functional or to be aesthetically pleasing?” But this is the wrong question to ask, in fact according to Papanek the question does not even make sense, because aesthetics actually is one of the elements of function. Papanek goes on to explain how in order to make a design function you need address six elements: method, need, association, use, telesis, and aesthetics (Papanek, 2020). As I said there is a lot to unpack from my visit to the graveyard of oral history technology so to give myself some structure I will use Papanek’s six elements of function to further dissect the triumphs and tribulations of my ancestors in an attempt to discover why they are no longer with us.

Use

I think it can be said the general aim of my ancestors is to use technology to help bring orality into the centre of archived oral history recordings and frame the recordings in a wider context. The designs were meant to be used to create a better listening experience. This is where the designs were mostly the same, their differences lay with access and format. Project Jukebox was, due to it being the 1990s, was not connected up to the internet, but projects like VOAHA, Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database and Montreal Life Stories, had a prime aim to make the oral history recordings as accessible as possible via the internet (Gluck, 2014; High, 2010). Similarly the creators of Stories Matters decided to make their software web-based instead of being a downloadable software like Interclipper (Jessee, Zambrzycki, and High, 2011; High, 2010). When we look at format things become a bit more vague, as it was only in retrospect Boyd labeled Project Jukebox, VOAHA, and Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database as well-curated exhibitions rather than an archives (Boyd, 2014). However, Steven High championed the digital storytelling in Montreal Life Stories, and in a paper on Stories Matters, it is mentioned that other database projects like The Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation and The Informedia Digital Video Library at Carnegie Mellon were seen as too archive-like (Jessee, Zambrzycki, and High, 2011). And of course some projects focused more on creating general software, while other focused on enhancing one particular set of oral history recordings. In conclusion, even though there was the overarching aim to focus of orality and wider contexts, the use of each design changed slightly depending on their attitudes towards access and format. These discrepancy suggest there is no universal idea under oral historians as to what they want these digital designs to be and do – what they want to use them for. I imagine there is a need for multiple designs: a good exhibiting tool for when oral historians want to present their findings, and a good storage and access tool, for after the end of an oral history project when everything is archived. But the latter is where something far more fundamental needs to be addressed by these designs.

If we return to Papanek, he starts his section on use with the question “does it work?”. Clearly, the designs in the graveyard of oral history technology no longer work, thus something within use of the designs was overlooked. If these projects aimed to be archives or tools to build archives they failed, because the main use of an archive is keeping things for a long time. This leads us back to Rob Perks and his writing on the relationship between technology, oral historians, and sound archivists. According to Perks oral historians are more likely to embrace new technology which makes recording easier, while sound archives are slightly more apprehensive since the longevity of the technology has not been proven. Permanent preservation of recordings is a priority for sounds archivists which sadly none of the designs I have discussed were able to achieve. In fact there is little to no mention of sound archivists in the articles on the projects in the graveyard and not including them might have contributed to their deterioration. Designs failing because certain people were not included in the design process is a common occurrence. One of the most famous examples is the Segway, which was heralded as the future of transport by Jeff Bezos and Bono. Sadly no one decided to asked town planners where the Segway could be ridden: the street or the pavement? Or wondered whether actual humans would use this, as you could not take your kids on it, do your weekly grocery shop on it, or commute long distance (Hall, 2013). Now, the projects I have been talking about are not close to being as horrendously tone-deaf as the Segway, but if they intended to create something which would last and be used as a type of archive then something was missing in the designs. That something brings us the original reason these technologies are needed—“The Deep Dark Secret of oral history” (Frisch, 2008).

Need

The general principle of “the Deep Dark Secret of oral history” is the painful reality that archived oral history recordings spend their time collecting dust rather then being listened to (Frisch, 2008). To solve the deep dark secret of oral history the design needs to last, like an archive, yet the projects I have discussed have not done that. They have address some of the issues Frisch discusses in his paper, Three Dimensions and More: Oral History Beyond the Paradoxes of Method, like orality and context, but not, as I said previously, the requirements set by sound archivists. However, as Perks highlights with his tales of Minidisc and such, technology is not known for its longevity. I would also add, while it is often believed that once something is on the internet it is there forever, the average life span of a webpage is in fact around a hundred days. Webpages and their accompanying links move about, are removed and go missing on the expansive network of the internet all the time causing all sorts of “link rot” (Lapore, 2015). Link rot is a phenomenon I experienced many times during my research into these projects, because while the projects no longer exist, the papers on them do and they contain all the original links which have now ‘rotten’ completely. What all of this highlights is “digital fragility”. Digital networks are complicated. If we look back to the MiniDisc it was only particular softwares and hardwares matching up—a particular network—that allowed use and access. In the twenty-first century digital networks are becoming increasing complicated and therefore increasing fragile, like a giant house of cards, one wrong move and everything comes crashing down (Floridi, 2017). What we have here is a radical disconnect between the need for a solution that last and the medium chosen by oral historians to solve the problem, which has proven to be rather unstable. I am not suggesting a complete abandonment of digital solutions but a better focus on how to use it in a way that will last and therefore addresses the fundamental need of archived oral history recordings to last beyond a hundred days.

Method

An underlying with problem with how we think about technology is the perception it will deliver us the future. A far more logical and realistic way to think about technology is not to look at the latest technological developments but the technology the average person actually uses (Edgerton, 2008). In the book, The Shock of the Old, the historian David Edgerton gives examples of historical uses of technology from horses being far more important to Nazi Germany’s expansion then the V2, to how more bikes are made every year than cars, to the truly insane amount of coal we consume now in comparison to the period of the Industrial Revolution. According to Edgerton there is no such thing as the modern era, just newer and older tools being used to muddle through life as we have always done. The area of oral history technologies is not exempt from this as Frisch and Douglas Lambert suggest a do-it-yourself approach by “rummaging around in our virtual toolbox” for more cost effective, quicker, and more efficient solutions the deep dark secret, as least for now while we wait for “the optimally imaginable tool” (Lambert and Frisch, 2013). Papanek also encourages DIY. More specifically, he discusses how the relationships between methods, materials, and tools all work together to create the foundation of a functional and responsible design. For example the log cabin was the result of a large amount of trees, the axe, and the process of the ‘kerf cut’ (Papanek, 2020, p. 7). There was no need to import skilled labours, tools or materials, it was all already there, it was to an extend DIY. This type of DIY not only delivers inventive solutions but also is likely to address the foundational needs of a group in areas like cost, and allow easier reparations, again good for cost.

If we now look at the designs found in the graveyard of oral history technologies and the processes, tools, and materials used to make them, we see little DIY and a heavily reliance on newer technologies. Project Jukebox had support from Apple Computers Inc.. During the development of Stories Matters a software developer from Kamicode. Others did utilise their university’s own IT department (Gluck, 2014). However, as I learnt from interviewing the archivist who helped set up the archive at BALTIC art gallery, each software developer often has a unique way of doing things. A consequence of this is that once a software developer moves on, trying to find another who can help maintain the software without overhauling it completely is a challenge. And in all cases updates within the new technologies or the complete abandonment of them led to the project collapsing. As I mentioned in the previous section on need, digital networks are incredibly fragile and the work needed to sustain them requires expertise not everyone has. Sticking to you “virtual toolbox” and older more established technologies might make creating a solution to the deep dark secret of oral history archiving easier to achieve within the structures it is built in.

Telesis

The structures we design in and how we make our designs synthesise with these structures Papanek refers to as ‘telesis’ element of design function. As he writes: “the telesic content of a design must reflect the times and conditions that have given rise to it and must fit in with the general human socio-economic order in which it is to operate.” (Papanek, 2020, p. 17). Others have referred to this a ‘product ecology’ (Tonkinwise, 2014). To explain how the design and its surrounding structure interact Papanek offers the example of Japanese floor mats, tatami, and a grand piano. The tatami fits within the Japanese culture of leaving your shoes at the door, but in Western society where we happily walk around inside in our high heels these rice straw mats would not last long. Then again a Western grand piano, which utilises the reverberations of stone walls, would not do well in a Japanese home of rice straw floors and paper walls (Papanek, 2020, p. 18). It is similar to the previous section on methods but boarder, including cultural habits and importantly the thing that makes or breaks most endeavours – money. Up to this point I have only briefly referred to it but funding or the lack there of was a recurring obstacle in many of the oral history technology projects and in many cases it delivered the final blow to the projects (Schneider, 2014; Gluck, 2014; Boyd, 2014; Lambert and Frisch, 2013). If we view this through Papanek’s idea of telesis then we can see how the developers were deeply focused on the design and less on the design’s ecology. There is the possibility that within a different structure which offered a steady supply of money the designs might have worked, as is the case of some of the living members of the oral history technology family. However, the majority of them were developed within the structure of a university where funding is scarce and not recognising this a start of the design process is probably one of the leading reasons as to why these projects ended up in the graveyard.

Association

There is another, more nebulous element of design function that also draws on the design’s wider context; the languages and associations we use to navigate the world. Within design association is a very powerful tool to assist users in using new products. The best examples of this are the document save button which looked like a floppy disk, and the early automobiles, whose design is clearly based off horse drawn carriages. Our familiarity with already existing products helps the designer integrate new products into society, but it is also the element of function where a huge amount of manipulation can take place (Papanek, 2020). For example in certain smartphone applications the refresh motion is purposefully designed to emulate a slot machine to replicate the addictive nature of slot machines to the applications keeping the user on there for longer (Orlowski, 2019). Whether the creators of the designs in the graveyard of oral history technologies intentionally tried to play on certain associations, like the above examples, or not, I do not know. Nevertheless, this does not mean associations were still not subconsciously made by the designers and users. As soon as people started putting oral histories online they moved into the sphere of association that surrounds the internet: the world of speed, efficiency, and entertainment. This move, as Anna Sheftel and Stacey Zembrzycki discuss in a paper on the affect digital technologies are having on oral history practice, might have made oral history recordings more consumable but a side effect is people are spending less time reflecting the wider context of the recording (Sheftel and Sembrzycki, 2017). Similarly, William Schneider also warns against the allure of technology: “technology, with its opportunities and constraints, can also take over our attention, and we can get carried away with the possibilities offered and lose track of the speakers and their narratives.” (Schneider, 2014) Associations are very powerful tool, not recognising them can cause all sorts of unforeseen consequences and therefore, like all the elements I have already discussed, need to be integrated into any design.

Aesthetics

The last element of function returns us to the question “should I design it to be functional or to be aesthetically pleasing?” or “do you want it to look good or to work?” (Papanek, 2020) Aesthetics are important because humans are very ruthless creatures, if we do not like the look of something or there is a second better looking version, we reject first version. The previously mentioned Segway was, among other things, also relentless mocked for the way it made people look (Hall, 2013). Many of the projects discussed did look nice and most of them were user friendly, but because this was the creators main focus the other five elements of function were forgotten and that had devastating effects. I hope that I have made it clear that the answer to the question is: you should make it look good and also all of the above.

Measuring my ancestors against Papanek’s elements of function has allowed me to break these designs and projects down into their various components and analys each in more depth, giving me a better understanding of what went wrong. I now know how the projects addressed issues around orality and context, but am still left a little confused about what exactly they wish to make: a software, an exhibition, an archive? I understand the base need to address the deep dark secret of archived oral history recordings, and how using newer technologies and relying on outsiders’ skills makes it difficult to maintain designs in the long run. I am aware of the influence the spaces and structures the design would operate in, like the funding system and the internet, have on the fate of the design. And finally I know designs need to look good, but it cannot be the only point of focus. The main aim is to create a balance between all of the elements of function, which Papanek suggests will result in a well functioning design (Papanek, 2020). Nevertheless, I still feel there is something missing from this investigation. I understand what information could have been gathered by the developers in order to create this balance between the elements of function, but I do not know how they should have done this and how this compares to their original development processes. In the next section I will revisit the projects’ processes and see how they compare to the various development processes you find in design.

Trial and error?

The majority of the things written about the development processes of these design involves discussing the relationship between the oral historians and the tech people. With the development of Stories Matters it seems a lot of pressure was put on the single software developer Jacques Langlois, especially when it came to tracking bugs in the software. There also was a disconnect between the desires of the oral historians, who were mainly focused on the userbility of the software, and Langlois, whose priority was to make sure the software did not crash and ran smoothly (Jessee, Zembrycki, High, 2011). Still this relationship seemed rather more collaborative than Project Jukebox where the relationship in one paper is rather crudely summarised to “all the computer specialist had to do was make it all work” (Lake, 1991). These development processes prove how difficult communication across disciplines can be in collaborative settings. You have to avoid solely sectioning off parts of the problem for individual disciplines to work on, like the comment from Project Jukebox suggests. Within design allowing or encouraging ‘conflicts’ through each discipline voicing their view of the problem can be used as creative stimuli (Sterling et al. 2018). An example of these “creative tensions” happened during the development of VOAHA when the oral historians desired contextual information be presented, they engaged to an in depth discussion with the IT experts in order to come to a conclusion that satisfied both parties (Gluck, 2014).

Yet collaboration does not have to be limited to those who are the producers, Michael Frisch and others who did work around Interclipper found great benefit in “hanging out a shingle” instead of sticking solely to their own project when they were developing ideas around the management of oral history recordings in digital environments (Lambert and Frisch, 2013). The design theorist Roberto Verganti highly encourages inviting many people from an extremely wide range of fields to come to look your work or design or problem. He refers to these people as ‘interpreters’ who are able to give a different perspective on a situation which might not have seemed obvious from the onset (Verganti, 2009; 2016). By harvesting these alternative perspectives on the problem in hand, the problem is no longer a fix concept but something that changes depending on the angle you view it at. This technique is often referred to as ‘reframing’ (Dorst, 2015). The reframing of the problem is intertwined with the development of the design. Kees Dorst and Nigel Cross give an example of this ‘co-evolution’ of design and situation, or problem and solution, in the paper, Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem-solution, where group of design students are given an assignment to find a new litter disposal system on Dutch trains. By the end of their design period one student had reframed the assignment to also included disposing of the waste from the toilets, which previously was simply emptied out on to the rails through a hole in the train. Another student had expand concept of the litter disposal system from within the train to a wider system across the entire rail transportation network, after all you have to get the litter off the train at some point (Dorst and Cross, 2001). By reframing the assignment both students simultaneously developed a design and their understanding of the problem.

Of course having an endless stream of people coming though you door voicing their opinion at you so you able to create creative tensions and use them to reframe your problem is not going to be helpful all the time. Therefore it is advised to build in moments of increased collaboration into the design process through the testing of prototypes and crit sessions, where you invite people to come critique your work. The latter allows for creative tension to take place, while the former offers slightly more practical feedback. The developers of VOAHA experienced the need for this practical feedback when they realised their search mechanism would return results that left out the carefully constructed contextual material assigned to each recording. Sadly, the people only discovered this after editing was no longer possible and so it could not be fixed (Gluck, 2014). An iterative process of developing a prototype, testing it, and then feeding the results back into the development is likely to have picked up this fault alongside other information.

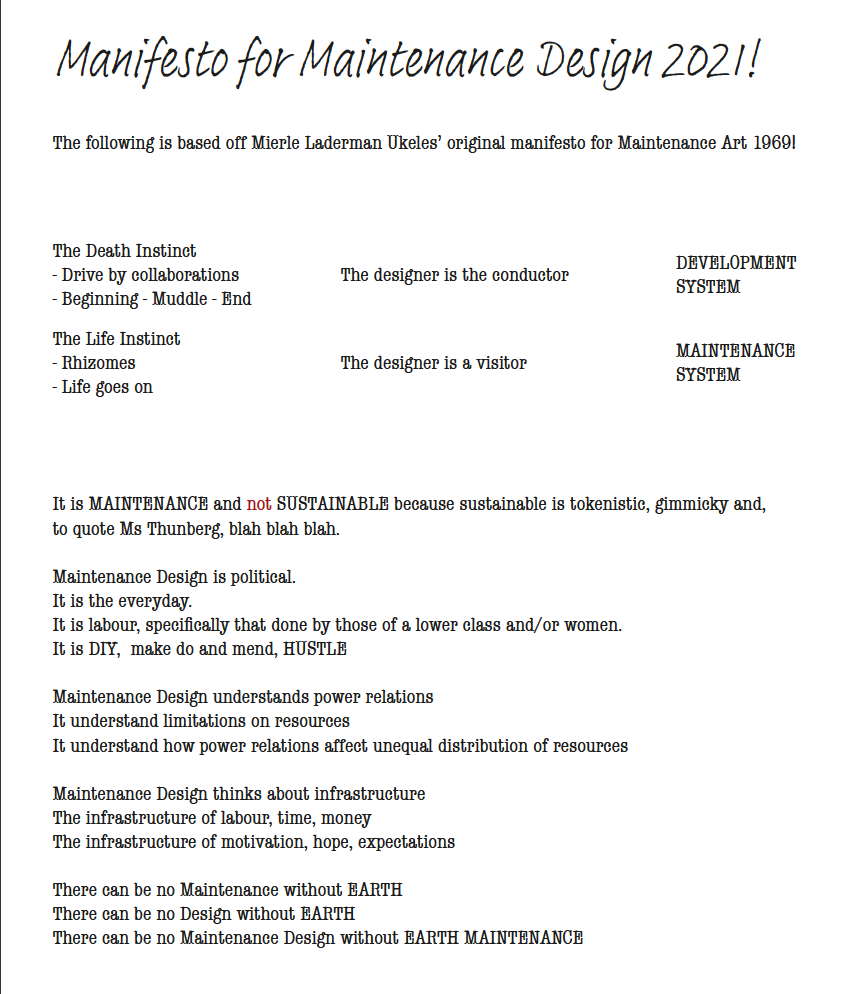

Looking at the design processes of the oral history technologies and comparing them to various design methods I now see how getting input from multiple people across disciplines, regularly testing out the design and then using this feedback to further development are all good ways to gather the information necessary to balance Papanek’s elements of function. But what do you then? During the development of Stories Matters there was extensive testing but it still ended up in the graveyard of oral history technologies (Jessee, Zembrycki, High, 2011). This is the point, after the development of the design and it has been released into the world, a designer becomes a gardener according to Ezio Manzini. Each object designed is like a plant and this plant is part of a bigger network of other plants like a garden. The designer is the gardener who plans and curates the garden, but also prunes, weeds, and composts the garden (Tonkinwise, 2014; Manzini and Cullars, 1992). The metaphor illustrates the continuous nature of design. It might start off with a period of initial development and testing, but after it is released into the world continuous maintenance needs to occur, just like a garden. But this is where is goes wrong and not just for my ancestors but for so many products because after iteration comes maintenance and to quote the writer of Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! Meirle Laderman Ukeles: “maintenance is a drag.”

Maintaining or destroying

In her manifesto Ukeles explains how the world can be separated into two systems “the Development System” and “the Maintenance System”. The Development System encourages the unadulterated making of stuff, while the Maintenance System is occupied with keeping the created stuff in good condition. Ukeles sums up the relationship between these systems with the question, “after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?” With this question she wishes to highlight how society values the Development System above the Maintenance System (Ukeles, 1969). Manzini with his garden would, I imagine, agree wholeheartedly with Ukeles. Maintenance is not really design’s “thing”. Cameron Tonkinwise, who quotes Manzini in a book chapter titled Design Away, even implies that the complete opposite is true and design is inherently destructive (Tonkinwise, 2014). Design is firmly part of the development system and has little interested in the maintenance, so when things break instead of fixing a new product is developed. And things will always break or in the case of Papanek’s elements of function, things will be thrown off balance and then break. All elements of function are subject to change. Our associations change, our taste changes, the wider world the design operates in will be radically different tomorrow. Maintenance’s task is to keep the balance between the elements stable through general repair, but also updating the design to better fit the ever-changing world we live in. To go back to the garden metaphor, you do your pruning and weeding, but sometimes you might need to make some more radical interventions, like when there is a climate crisis which means you can grow grapes in Newcastle but also have everything ripped from the roots in the third storm of the month. However instead of maintaining the garden, according to Tonkinwise, modern society’s answer to this the instability is to constantly produce new things destroying old ones in the process (Tonkinwise, 2014). The graveyard of oral history technologies is proof of this, not because I think this is the attitude of the individual developers, but because the system did not allow them to do otherwise. Nearly every paper on the project mentions running out of money (Smith, 1991; Boyd, 2014; Gluck, 2014; Lambert and Frisch, 2013). The option to maintain existing designs or build upon older ones was never there.

Design takes time. It takes time to develop and it takes arguably an infinite amount of time to maintain. Time is money which my ancestors did not have. If they did then maybe they could have had a iterative design process filled with creative tensions and prototype testing, allowing them to fulfilled Papanek’s six elements of function, making them produce an amazing design that was able to be consistently maintained for many years. But they were never really given a chance, instead they had one shot and in this case it missed. However they left me a mountain of knowledge to take with me on my own journey, but before I embark on this venture it is probably also wise to briefly visit the living members of the oral history technology family.

Listen to your elders

The oldest living member of the oral history technology family is the Shoah Foundation, previously The Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, which was set up by the film director Stephen Spielberg in 1994 (Frisch, 2008). Now the survival of this particular project is most due to the very high level of support and backing they have consistently received over the years (Boyd, 2014). The other two are the Australian Generations Oral History Project and Oral History Meta-data Synchroniser or OHMS. The Australian Generations Oral History Project is a collaboration between academic historians, the National Library of Australia and Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Radio National with a good amount of funding (Thomson, 2016). Oral History Meta-data Synchroniser or OHMS is a web-based software developed by Doug Boyd after his work on the Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database. There are many parallels to be found in the design of these technologies and their ancestors, so I will not repeat myself. However, there are still things to be learnt, particularity in the two areas these project are grappling with – ethics and scalability.

How to be good

The idea of access and the ethics of it has become a large area of discussion within the oral history technology community (Bradley and Puri, 2016). During the development of the ancestors people were already aware they might need to advise student to “never ask a question you don’t want the world to hear via the web” (Gluck, 2014, p. 43). On the other hand with Project Jukebox, ideas around copyright seem a little all over the place as they were mainly worried about the copyright of photographs and not the recordings (Gluck, 2014; Lake, 1991). Managing ethics, access, and the internet is, to use the title of Mary Larson’s paper on the subject, an exercise of “steering clear of the rocks” (Larson, 2013). The Shoah Foundation has managed this by only letting people who pay to have access (Levin, 2003), but back in the graveyard many of the ancestors wanted to use the internet because it granted more access (Gluck, 2014; Jessee, Zembrycki, High, 2011; High 2010). This spirit lives on in the Australian Generations Oral History Project and OHMS.

The access/ethics structure of Australian Generations Oral History Project was designed to allow a level of access the internet promises, while also protecting interviewees. It therefore starts with the interviewee having complete control of the recording for the duration of their lifetime through a rights agreement contract. In the rights agreement the interviewee can agree or disagree to their recording being used, before or after a certain date, in four different scenarios: “listening in the library’s reading rooms for research purposes, procurement of a copy that a user can have at home, exposure through the library’s website, catalogue and collection delivery system, or publication by a third party.” And the interviewees are then allowed to change their mind at point. This part of the access/ethic structure is the “legislated ethical component” (Bradley and Puri, 2016). This refers to Mary Larson’s article, Steering Clear of the Rocks: A Look at the Current State of Oral History Ethics in the Digital Age, where she divides debate surrounding ethics into “legislated (what one can do) and voluntary (what one will do)” (Larson, 2013, p. 36). The “voluntary ethical component” of the access/ethics structure of the Australian Generations Oral History Project involved the ethical judgments originating from the content of oral history recordings that need to be handled by humans (Bradley and Puri, 2016). It is these ethical judgements were the shortcomings of technology and the digital age become most apparent. In his book, The Design of Future Things, Donald Norman paints the scenario of a smart house that turns on the lights and the radio when its residents get out of bed in the morning. However, when a person decides to get out of bed in the middle of the night because they cannot sleep, the house also turns everything on and wakes up the person’s partner (Norman, 2009). The technology is not advanced enough to understand the slight differences in this scenario let alone the complex ethical issues the Australian Generations Oral History Project handles. In these cases human still have the edge above technology, which undoubtedly important to remember when designing any technological solution.

Making it big

Currently the biggest challenge facing OHMS is the scalability of the technology. Initially OHMS was only available as the in-house software for the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky Libraries, however in 2013 Boyd writes how they had received a grant to start the process of making the software ready of open-source distribution (Boyd, 2013). When I consider the challenge I am reminded of two things I learnt from investigating those in the graveyard of oral history technology. The first one is Manzini’s garden and gardener metaphors and the importance of maintenance, which Boyd completely acknowledges in his paper on the software: “open-source tools must be designed with sustainability in mind in order to be truly successful. […] We will actively engage [the user] community to provide feedback and information that will allow for effective and ongoing development and for the future innovation of this freely available tool” (Boyd, 2013, p. 105). The second one I am reminded of is Papanek’s function element of telesis and how he warns “it is not possible to just move object, tools, or artefacts from one culture to another then expect them to work” (Papanek, 2020, p. 17). The main idea behind open source software is that anyone can use it but as the element of telesis suggests it might not necessarily be true due too digital inequalities. The “digital divide”, a termed coined in United States during 1990s initial referred to the differing levels of access to hardware, software, and the internet. However since then the idea of access has been broadened to include the skills needed to access and retrive information and increasingly, the skills needed to communicate through various mediums, and create content. The reason for this expansion is because people realised that digital inequalities did not disappear in places where there was unilateral physical access to digital technologies (Van Dijk, 2017). Therefore ideas like free open access, which I personally find a noble venture, might only really benefit those who have the digital tools and skills to use them.

Both scalability and the ethics of access feel (for now) like the last two hurdles oral history needs to get over before we finally achieve the dream of solving the deep dark secret of oral history. But they are rather large problems and I imagine if history is anything to go by there are many more mistakes to makes and learn from before we solve them.

Conclusion

Let us go back to our feelings around the MiniDisc. How does it make you feel? Nostalgic? Repulsed? Disappointed? Or do you feel, as I do, a strange sort of pride? Because it takes courage to dive into technology, but it takes even more to pick yourself up after things fail, and salut your failure and thank them for the ride. Not doing this is, as Matthew Syed writes, is like playing golf in the dark – how are you going know how to get closer to the hole? (Syed, 2020) Now I have not yet started metaphorically playing golf but I have been able to watch my ancestors and elders give it a good swing. However, when I step onto the green I do not believe I will get a hole in one. I will not solve the problem of oral history’s deep dark secret. I will not make a system that is the perfect listening experience which will last forever, mostly because I cannot afford it. Instead my aim is to make mistakes and fail as much as I can, so that someone else can learn from my work just like I have done from those who came before me. The mission to find “the optimally imaginable tool” (Lambert and Frisch, 2013) will not end with me and it is likely to never end because the world keeps changing so innovation is never truly done.

Bibliography

Bradley, K. and Puri, A. (2016) “Creating an oral history archive: Digital opportunities and ethical issues” in Australian Historical Studies. 47(1) pp.75-91

Boyd, D. (2013) “OHMS: Enhancing Access to Oral History for Free” in The Oral History Review. 40(1) pp. 95-106

Boyd, D.A. (2014) ““I Just Want to Click on It to Listen”: Oral History Archives, Orality, and Usability” in Oral History and Digital Humanities. pp. 77-96. Palgrave Macmillan: New York

Dorst, K. (2015) “Frame creation and design in the expanded field” in She Ji: The journal of design, economics, and innovation. 1(1) pp.22-33

Dorst, K. and Cross, N., 2001. Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem–solution. Design studies. 22(5) pp.425-437

Edgerton, D. (2008) The shock of the old : technology and global history since 1900. London: Profile

Floridi, L. (2017) “The unsustainable fragility of the digital, and what to do about it” in Philosophy & Technology. 30(3) pp.259-261

Frisch, M. (2008) “Three Dimensions and More” in Handbook of Emergent Methods. pp.221-238. Guilford Press: New York

Gluck, S.B. (2014) “Why do we call it oral history? Refocusing on orality/aurality in the digital age” in Oral History and Digital Humanities. pp. 35-52. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Hall, E. (2013) Just enough research [ebook] New York: A book Apart

High, S. (2010) “Telling stories: A reflection on oral history and new media” in Oral History. 38(1), pp.101-112

Jessee, E., Zembrzycki, S. and High, S. (2011) “Stories Matter: Conceptual challenges in the development of oral history database building software” In Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 12(1)

Kelly, T. and Kelly, D. (2013) Creative Confidence: Unleashing the Creative Potential Within Us All. William Collins: London

Lake, G.L. (1991) “Project Jukebox: An Innovative Way to Access and Preserve Oral History Records” in Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists. 9(1), pp.24-41

Lambert, D. and Frisch, M. (2019) “Digital curation through information cartography: A commentary on oral history in the digital age from a content management point of view” in The oral history review. 40(10). pp.22-27

Larson, M. (2013) “Steering Clear of the Rocks: A Look at the Current State of Oral History Ethics in the Digital Age” in The Oral History Review. 40(1), pp.36-49

Lepore, J. (2015) “The Cobweb: Can the internet be archived” in The New Yorker. January 26 2015 issue

Levin, H., 2003. Making history come alive. Learning and Leading with Technology, 31(3), pp.22-27.

Manzini, E. and Cullars, J. (1992) “Prometheus of the Everyday: The Ecology of the Artificial and the Designer’s Responsibility” in Design Issues . 9(1) pp. 5-20

Norman, D. (2009) The Design of future things. New York: basic books

Orlowski, J. (2020) The Social Dilemma. [FILM} Netflix: United States

Papanek, V. (2020) Design For The Real World: third edition. London: Thames & Hudson

Perks, R.B., 2011. Messiah with the microphone? Oral historians, technology, and sound archives. Ritchie, The Oxford Handbook of Oral History, pp.315-32.

Schneider, W. (2014) “Oral history in the age of digital possibilities” in Oral History and Digital Humanities ed. D. Boyd and M. Larson. pp. 19 – 33. Palgrave Macmillan: New York

Sheftel, A. & Zembrzycki, S. (2017) Slowing Down to Listen in the Digital Age: How New Technology Is Changing Oral History Practice, The Oral History Review, 44:1, pp. 94-112,

Smith, S. (Oct 1991) “Project Jukebox: ‘We Are Digitizing Our Oral History Collection… and We’re Including a Database.’” at The Church Conference: Finding Our Way in the Communication Age. pp. 16 – 24. Anchorage, AK

Sterling, N., Bailey, M., Spencer, N., Lampitt Adey, K., Chatzakis, E. and Hornby, J., 2018, August. From conflict to catalyst: using critical conflict as a creative device in design-led innovation practice. In Proceedings of the 21st Academic Design Management Conference (pp. 226-236).

Syed, M. (2020) Black Box Thinking. John Murray (Publishers): London

Thomson, A., 2007. Four paradigm transformations in oral history. The oral history review, 34(1), pp.49-70.

Thomson, A. (2016) Digital Aural History: An Australian Case Study, The Oral History Review, 43:2, 292-314,

Tonkinwise, C. (2014) “Design Away” in Design as Future-Making. pp. 198 – 214. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc: London

Ukeles, M. L. (1969) Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!

Van Dijk, J.A. (2017) “Digital divide: Impact of access” in The international encyclopedia of media effects ed. P. Rössler. pp.1-11. John Wiley & Sons

Verganti, R., 2009. Design driven innovation: changing the rules of competition by radically innovating what things mean. Harvard Business Press: Cambridge

Verganti,; 2016 Overcrowded: Designing meaningful products in a world awash with ideas. The MIT Press: Cambridge