Tag Archives: maintenance art

OHD_PRS_0203 Capturing voices: Designing a system for better oral history reuse

For paper that is title “designing a system for better oral history reuse” I am not going to spend a lot of time talking specifically about oral history or design. The reason for this is because designing a system for better oral history reuse involves a whole bunch of topics, which for the sake of this talk I decided to map for you to give you a better picture of my work. This is a pretty rough map, there are many things I can talk about and I realise that there are also many overlapping and interconnected themes and all of this will probably change in a week. I am not going to spend my precious ten minutes talking you through this whole map. Instead I am going to expand the themes that I am currently interested in at this point of my journey.

In 1969 Mierle Laderman Ukeles published her Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!, in which she describes how the world consists of two systems: Development and Maintenance. Development involves the creation of stuff, while Maintenance is about keeping the created stuff in good condition. This theory also applies to Oral History, the Development is recording the oral history and Maintenance is the archiving and reusing of those recordings. Now my research does have a Maintenance focus but in order to do Maintenance you still need to have Development and currently I am doing some development. I am recording oral history interviews with people and I have recently come across a very interesting problem that I am going to talk about first and then I will move on to Maintenance part which is also offers plenty food for thought.

“When I was being trained in museums, conflict over cultural heritage was a constant source of surprise – like the first hot day each summer, when, year after year, one is somehow shocked by what are, in fact, seasonable temperatures.”

I find this a very amusing comparison by Liz Sevcenko, who was Founding Director of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience, which is a network of historic sites that foster public dialogue on pressing contemporary issues. The institutes within this coalition are often sites of very intense trauma with many of the sites handling issues like genocide, war, and other atrocities.

This is Seaton Delaval Hall. Built in the 1720s the hall and its residents, the ‘Gay Delavals’ became renowned for wild parties and other shenanigans. In 1822 the hall went up in flames severely damaging the property. In 2009 after the death of Lord and Lady Hastings the property was taken over by the National Trust. A face value Seaton Delaval Hall is not necessarily like the institutes that make up the Sites of Conscience. It is a National Trust property near the sea, it has a nice rose garden, and a cafe that does excellent scones. But it is also a grand hall built in 1720s in Britain, which can only really mean one thing the Delavals, who were the family that lived in the hall, got some of their income from the British Empire. This is from a report done by the National Trust addressing various properties history with slavery and the British Empire. Sevcenko is right, summers are warmer than winters and there is conflict in all cultural heritage sites no matter how twee they look.

In a paper about the Sites of Conscience Sevcenko points out “Heritage can never be outside politics – it is always embedded in changing power relations between people”. Seaton Delaval Hall and many other National Trust properties are no exception, however these changing power relations go far beyond the British Empire.

A couple of weeks ago I meet the child of the old estate manager who, their whole life, lived and worked in the hall until they had to move out of the East Wing due restoration work, I will refer to them as Robin. Robin remembers when a different family the Hastings lives at the hall. Lord and Lady Hastings lived at the hall until their deaths in 2007, nearly also long as the original Delaval family. During their time there, the Hastings opened the hall to the public and regularly threw medieval banquets to raise money for the restoration of the hall. Robin also remembers the German Prisoners of War who were held at the hall during the Second World War. Their whole life Robin has been witness to the changes at the hall seeing it gradually evolve over time.

But Robin’s history does not really fit with the narrative the National Trust has for the hall. For those who are unfamiliar with the National Trust a lot of the properties are very busy with the idea of “spirit of place.” Seaton Delaval Hall’s spirit of place is deeply connected to the original Delaval family, who were known to be pranksters and excellent party people, think 18th century Gatsby, only with the aforementioned connections to the British Empire. A lot of the hall’s promotional material is built around this and it has functioned as a source of inspiration for various installations. The history that Robin remembers is seemingly under represented at the hall, because it does not really fit with this spirit of place.

To a certain extent I am trying to solve this particular problem by recording oral histories however in the case of Robin I have come across a problem. Due to their relationship with the National Trust Robin refuses to speak about their history with the National Trust. They will only give me stories from before the National Trust took over. This is because they know that if archived their recording will be donated to the National Trust archive. This means I cannot record the oral history I would like to because of current power structures.

To recap the political situation of the hall: firstly we have the hall’s connections with the British Empire, which nationally is slowly being addressed with things like the report and yet the hall’s spirit of place I feel is currently not fully considering these connections. And then we have a more recent power dynamic with Robin and the more recent history which clashes with the spirit of place. In case you were wondering Robin is not alone there are some local people who are also not happy with the National Trust.

Liz Sevcenko concludes in her paper on the Sites of Conscience that:

Sites of Conscience do not try to suppress controversy in order to reach a final consensus. Instead of being regarded as a temporary problem to be overcome, contestation might be embraced as an ongoing opportunity to be fostered.

The National Trust might decide to stop suppressing the narrative of slavery and move away from the glorification of those who benefited from the crimes of the British Empire, but this does not solve new power dynamics that are appearing, the one blocking Robin from telling their story. In order for Seaton Delaval Hall to become a Site of Conscience, they need to be open to criticism now. They need to open up a dialogue and allow the historical narrative to change and morph over time.

So the Development side of my work is very complicated but it is essential that I do not get to bog down in the Development because that is the reason why I am doing this CDA in the first place. Currently within oral history there is a preference to record over reuse. As the oral historian Michael Frisch describes oral history archives are like “a shoebox of unwatched home videos.” This valuing Development over Maintenance is exactly what Mierle Laderman Ukeles addresses in her manifesto and her art. The big reason for the inequality according to Ukeles is because Maintenance involves tasks that are either seen as domestic and ‘feminine’ or labour done by the working class.

However, this under valuing of maintenance can have really annoying consequences for example, I always get frustrated when I clean my fridge. There are so many little ridges that stuff gets into it is infuriating. As a designer I know that this problem could easily have been avoided if someone has just asked a cleaner some questions about how they clean a fridge. But they didn’t because people do not value maintenance. But in reality cleaners are extremely powerful, if cleaners go on strike you have a big problem.

Archivists are also part of the Maintenance system. In an article title ‘When The Crisis Fades, What Gets Left Behind?’, a direct quotation from Ukeles’ manifesto, Charlie Morgan, who is the oral history archivist at the British Library, describes how there was a rush to record the varied COVID-19 experience, but little thought was put into how the recorded material will be stored, let alone archived.

This article reminded me of a meme my friend sent me a couple of months ago, because Morgan did not treat ‘the archive’ as a concept but as a physical institution with staff, coffee machines, and opening times. Shortly after reading this article I had a meeting with the lead archivist at Tyne and Wear Archives Newcastle. They echoed both Morgan and Ukeles when they explained that the reality of being an archivist means you spend the majority of your time on management tasks rather than on the act of archiving. I need to bring these ideas of maintenance and the everyday archive into my development and design of this oral history reuse system. I cannot be like the fridge designers and forget about the person who cleans the fridge, because cleaners are powerful and archivist are the maintenance staff of our history. If archivists stop doing the maintenance then we are in deep trouble.

Rounding it off. One of the founding ideas behind oral history is that it gives a voice to the voiceless, however this has now become an outdated view as you can see from the things I have outlined here. Firstly, I currently am experiencing a situation where I am unable to give a voice to the voiceless because of the power structures that are present in at hall between people like Robin and the National Trust. And secondly if oral history does give a voice to the voiceless but then does not consider how to keep that voice alive by neglecting ideas around sustainable archiving and maintenance, then that voice is again lost. The aim of my project is to incorporate these ideas into my design for this oral history reuse system that will be housed at Seaton Delaval Hall.

I hope you enjoyed my little talk on what I am currently obsessed with within my web of topics. If you ask me in a couple of weeks time what I am thinking of it will probably be something completely different.

OHD_WRT_0136 Maintenance Design Essay

My mind map for my essay on Maintenance Design – OHD_MDM_0159

After the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?

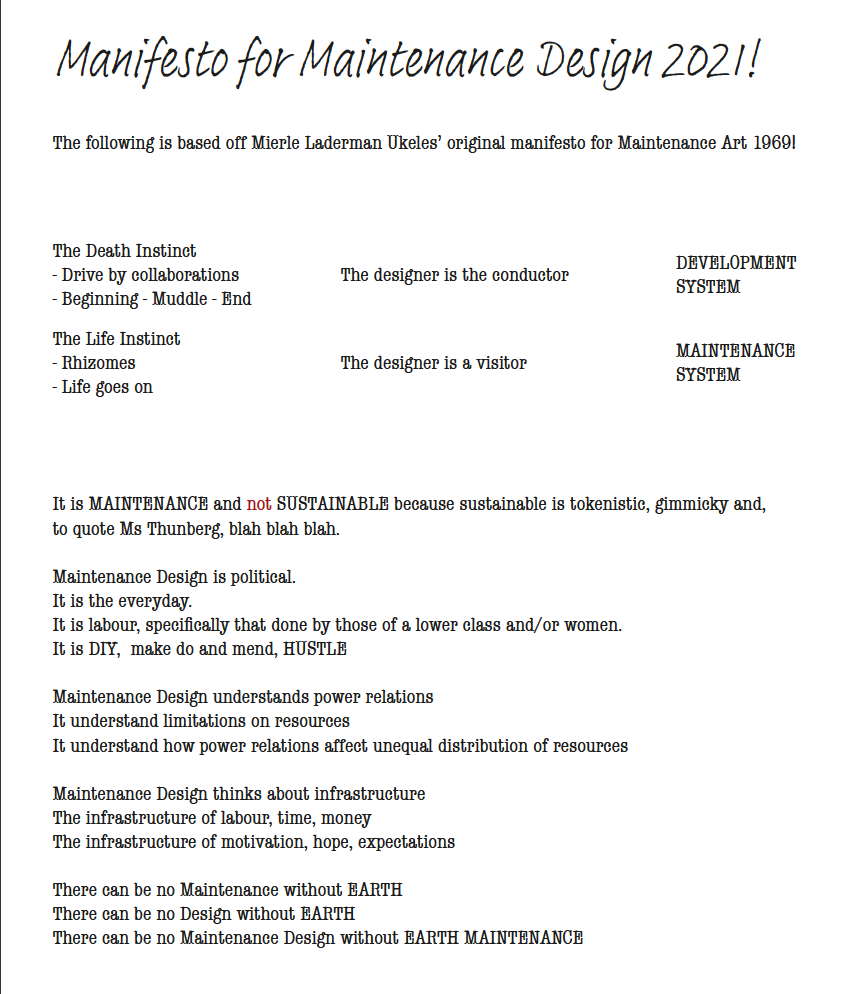

This is a quote from Mierle Laderman Ukeles Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! In the manifesto Ukeles splits the world into two systems: Development (the Death Instinct) and Maintenance (the Life Instinct). Development System is about “pure individual creation; the new; change; progress; advance; excitement; flight or fleeing.” In today’s society we love development; we love a revolution; we love disruption; we love innovation. You can find our love for revolution and the Development System everywhere: in art, design, science, politics etc. It often involves an individual, who is confronted with obstacles or injustice, which they then overcome, and then they are rewarded for their hard work. The Development System is a type of Hero’s Journey. The Development System believes the lone creative myth. The Maintenance System’s role is to “keep the dust off the pure individual creation.” The Maintenance System is what happens after the happily ever after, after the revolution.

In art school I knew exactly what happened after the revolution. At the end of each year the art department would hire four humungous skips, which were filled with the contents of the art studios. I always thought this to be a deeply ironic moment, where a group of avant-garde hippies, the majority of which were vegans would throw away so many resources without a care in the world. Here “pure individual creation” is made and dumped (Ukeles). The structure of a PhD is not that different to a BA in Fine Art. In an art degree you make art, while the aim of the traditional PhD is for you, the individual, to create new knowledge. It is, again, a classic Hero’s Journey and fits perfectly into Ukeles’ Development System. The creation of the art and knowledge is valued above the work required sustain the knowledge or art. I am working on a Collaborative Doctoral Award (CDA) which is similar in structure to a PhD but with the difference that I am working in collaboration with a non-academic institution. In my case this institution is the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall. This collaboration has got me thinking about Ukeles’ question: “After the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?” After my CDA, what is going to happen with my work and what is going to happen with my collaboration partner?

While reflecting on these questions I realised I feel a responsibility to not leave the National Trust high and dry when the money runs out. I do not want my project to turn in to a drive-by collaboration. I want it to have legacy. I want my project to live beyond the Development System and the Death Instinct. I believe this to be especially important because I am working on a project in the heritage sector. The heritage sector might be obsessed with death, but in reality Seaton Delaval Hall, the property I am collaborating with, is full with people who are alive. The access to the dead people’s history only exists because of those who are alive are telling their stories. I therefore declare that I must practice:

Maintenance Design!

But how does one achieve Maintenance Design when the structure of the CDA is part of the Development System? I believe the answer lies in how I frame my work and specifically what language I use to describe this framing. I decided to first look at some of the language used in the field of design that I believe reenforces work within Development System. I then will look at how the use of organic and natural metaphors, including the Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of the Rhizome, are better in helping designers map complex design situations; supporting them in producing work within the Maintenance System; and allowing designers to achieve good Maintenance Design.

The fuzzy front end is dead, long live the Rhizome

If I was to view my project through the lens of the Development System, I would describe myself as floating about in the “fuzzy front end” trying to tame a “wicked problem”. Wicked problem is used by designers to describe the nature of the problem you are trying to solve. (Rittel & Webber) The fuzzy front end is used to describe the beginning of the design process and the process of defining this wicked problem. (Smith & Reinertsen) I find that both terms belong in the Development System because they both suggest a finite amount of time. “Front end” suggests the existence of a back end, and “problem” is something that can be defined and therefore is static. (de Mella Freire, p. 91) Yet these terms simultaneously recognise the complexity of design situations through the addition of “fuzzy” and “wicked”. This is no unusual in the field of design. Early on in my masters in Multidisciplinary Innovation I raised my eyebrow at the continuous conveyer belt of toolboxes, methods, and diagrams that all tried to squeeze the design process into a quantifiable amount of time. At the end of my first term, a fellow student sent me a link to a talk by the Pentagram graphic designer, Natascha Jen, titled Design Thinking is Bullsh*t. It resonated with me. Jen was frustrated by the design process being condensed into easy-to-follow steps. She scathingly dubbed it “fast food thinking.” (2018) As a trained designer she was clearly worried by her field of work being squeezed into a sellable product. The words you frequently find in Design Thinking literature and alongside the diagrams Jen is so frustrated remind me of the word Ukeles used to describe the Development system: “The new; change; progress; advance; excitement”. Unlike Jen I do think there is value in some of these diagrams, toolboxes, and methods, but I do struggle with how they confine the “fuzz” to specific amount of time, especially when you consider the value of good and extensive research.

In the paper, Collaborative Problem Solving Through Creativity in Problem Definition: Expanding the Pie, Albert Einstein’s answer to the question “What would you do if you had an hour to save the world?” is used to illustrate the importance of research when trying to solve a complicated problem. Einstein answered the question by saying “I would spend 55 minutes defining the problem and then five minutes solving it.” (p. 62) This attitude is not reflected by the diagrams and methods issued by the various design institutions, like IDEO and Stanford’s d.school (fig. 1). It is also not what I experience during my masters. From what I remember research was often dropped in favour for creating more tangible solutions and deliverables. I imagine that Einstein’s approach would have generated a lot of stress, because we very much operated in Ukeles’ Development system. We were fixated on creating a revolution, not thinking about what would happen after. Erika Hall explains in her book Just Enough Research, why research is often neglected in design projects. Firstly, research means giving up a lot of time and money, and secondly, it means “admitting you don’t have all the answers.” (p. 3) In a world where the myth of the lone creative genius is rife, it is hard to admit that you might not know everything, especially if finding out will take time and money. And sadly, my CDA is structured around time and money.

Let us say that we put aside terms like “fuzzy front end” and “wicked problem”, and all the step-by-step diagrams and methods, what alternative language is there available in the design world? The design theorists Kees Dorst and Nigel Cross discuss how the co-evolution of problems and solutions is key to creativity in the design process. Dorst and Cross write about the time spent defining the problem in a way that does not restrict it to the front end, but has it run throughout the whole design process. (p. 432) In a paper titled, A design-approach to transforming wicked problems into design situations and opportunities, Bailey et al. use the idea of the problem and solution evolving together to demonstrate the transformation of “wicked problems” into “design situations and opportunities” (p. 95). By using words like co-evolution, situation and opportunities instead of problem Dorst and Cross, and Bailey et al. articulate how research is continuous throughout the process of designing and is not restricted to the beginning. In the paper, From strategic planning to the designing of strategies: A change in favor of strategic design, Karine de Mella Freire, from the Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos discusses another possible framing of design problems that also does not limit the time for research. De Mella Freire uses the metaphor of design problems being like machines to describe design projects where the terms “fuzzy front end” and “wicked problem” are used. (p. 91) The metaphor of the machine illustrates an enclosed, linear problem that can be easily fixed by replacing or adding a part without there being any consequences to the wider system. As alternative de Mella Freire proposes using more organic and natural metaphors to help illustrate design problems as a network of interconnecting and ever changing things, allowing room uncertainty and dynamic shifts. The language used by de Mella Freireis is similar to the co-evolution of Dorst and Cross, and Bailey et al., however she specifically draws on a post-modern way of thinking. (p. 91) And although she does not directly reference Deleuze and Guattari there are clear similarities behind de Mella Freire’s desire to understand “the world according to the epistemology of complexity”, and Deleuze and Guattari’s idea of the Rhizome.

In botany the term “rhizome” is used to refer to an organism’s network of roots and shoots that is mostly found underground. Ginger and turmeric are examples of a rhizome. In philosophy the rhizome was first used as a metaphor by Deleuze and Guattari in their “root” book, A Thousand Plateaus. The rhizome is basically a tool that can be used to help people think about the dynamic interconnection of things. Deleuze and Guattari list six principles that make something a rhizome:

1 and 2. Principles of connection and heterogeneity

“Any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be” (p. 27). The Rhizome is non-hierarchical. You can be dropped into the rhizome at any point and explore from there. There is no set path.

3. Principle of multiplicity

“A multiplicity has neither subject nor object, only determinations, magnitudes, and dimensions that cannot increase in number without the multiplicity changing in nature.” (p. 28). In order words, actions and change have consequences. For example, if you increase the temperature in the room you feel warmer.

4. Principle of asignifying future

“A rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines.” (p. 29)

5 and 6. Principle of cartography and decalcomania

“The rhizome is […] a map and not a tracing.” The rhizome was not made from blueprint, it is not a tracing of something that already existed. However, the rhizome can be mapped in order to be better understood. (p. 32)

De Mella Freire’s metaphor of design problems being like machines goes against the principles of the Rhizome. A machine is built from a blue print; it is an enclosed system; if a piece of the machine breaks and is not replaced the machine will stop functioning. However, de Mella Freire encouraging designers to drop ideas around external and internal actors, and focus more on the relationships between actors, is an attitude that fits perfectly into the concept of the Rhizome. (p. 91) The concept of the Rhizome helps me understand the scale of the problem I am dealing with. It allows me to be open to change and new information throughout the project instead of a designated section of time at the beginning. The Rhizome becomes a tool or a mindset that supports me in creating (some) structure in my research, while not becoming completely overwhelmed.

Making maps

In some design literature the act of mapping a network or a rhizome is referred to as “infrastructuring” a design situation. The term “infrastructuring” has its history with information infrastructure which was first introduced by Susan Leigh Star and Karen Ruhleder in their paper, Steps toward an Ecology of Infrastructure: Design and Access for Large Information Spaces. Star and Ruhleder write about the paradoxical affect technology has on an organisation, “It is both engine and barrier for change; both customizable and rigid; both inside and outside organizational practices.” (p. 111) The reason for this according to Star and Ruhleder is because the unique infrastructure of individual organisation makes it impossible for a technology to completely adapt to the needs of each organisation. In addition, Star and Ruhleder describe how the infrastructure of organisations are not enclosed systems but in fact extend across geographical barriers and the parameters of the group. Individuals within the organisation are often part of the multiple groups and therefore become bridges to other organisations and communities. Because of the rhizomic nature of organisations, Star and Ruhleder emphasises the importance of understanding the infrastructure before you attempt to implement any new technology (or system). Similarities can be drawn between infrastructuring and the fifth and sixth principle of the Rhizome, the principle of cartography and decalcomania, the mapping of the Rhizome. However I believe there is a slight difference in their framing which decides whether the design project falls into the Development or Maintenance System.

I want to illustrate this difference by using a metaphor of a visit to a city. A city has many properties that are like a rhizome: the flow of people, transport systems, culture and identity etc. (Although I do recognise that some parts of the city have been created from blueprints.) Like a rhizome there is no beginning to a city but there are different entry points. If I visit a city, my experience of the city starts at one of these entry points. As I walk through the city I gain information about it, slowly building up my idea of the city. The city is the unmapped rhizome and my path through the city is my map of this rhizome. I believe that the difference between infrastructuring and the concept of the Rhizome is that infrastructuring relies too much on the map, while the concept of the Rhizome understands that the map is only an articulation of a situation at a specific time by a particular person and the city will be different tomorrow. Designing while omitting the fact that the rhizome/situation will change puts you straight into the Development System, because there is a lack of recognition of what will happen once your design has been implemented. In de Mella Freire’s paper, the way she labels that designer’s role in mapping the rhizome or infrastructuring as “problematizer” fits with the concept of the rhizome. According to de Mella Freire the problematizer’s role is to “question the status quo, to discover emergences, indicators of change to the environment, and to develop strategies in support of reorganising the system, in such a way that it adapts and continues to exist.” (p. 91) De Mella Freire identifies that the design must understand the “indicators of change” and create something that “adapts and continues to exist”. The latter in particular is part of the Maintenance System and Maintenance Design because it knows what will happen after the revolution/the end of the design project.

Let’s have hope

In an article titled, Against positivity design, the designer Danah Abdulla discusses how she is against optimism in design, particularly the “performance of positivity.” Optimism is often seen as an essential ingredient in design – there is not such thing as a bad idea. However this “performance of positivity” suppresses criticism. When Natascha Jen voiced her unhappiness with the “fast food thinking” of design thinking diagrams, she specifically highlights the lack of criticism in these diagrams. According to Jen, criticism and the event of the “crit” is essential in her own practice as a designer. Abdulla supports this idea and in her article goes on to describe how this optimism is part of a “culture of convenience” that plagues our capitalist society. Our societies pursuit for convenience makes lazy designers according to Abdulla. I will be the first to admit that the concept of the rhizome is not the easiest and designing via a map of a certain design situation is far more convenient. A map makes it a lot easier to identify and solve various problems and then produce a perfect solution that perfectly fits the situation articulated in the map. But as Star and Ruhleder point out organisations are not enclosed systems, so thinking about them in this way is, in the long run, unproductive.

Abdulla does offer an alternative to this “performance of positivity”. She does not want to kill all optimism but rather switch it for hope. In the article Abdulla quotes the political activist Barbara Ehrenreich from her 2009 book Smile or Die: “Hope is an emotion, a yearning, the experience of which is not entirely within our control. Optimism is a cognitive stance, a conscious expectation, which presumably anyone can develop through practice.” No matter how optimistic we are the rhizome will never fully be mapped. I find that having hope as the accompanying emotion to the Rhizome makes it a little easier to work with it because they are both simultaneously insecure and inspirational. So at the end of our journey we have a rhizome and hope. This is not a lot but it might be a way for me to frame my CDA in a way allows me to think beyond the revolution.

Bibliography

Bailey, M., Chatzakis, E., Spencer, N., Lampitt Adey, K., Sterling, N. and Smith, N., 2019. A design-led approach to transforming wicked problems into design situations and opportunities. Journal of Design, Business & Society, 5(1), pp.95-127

Basadur, M., Pringle, P., Speranzini, G. and Bacot, M., 2000. Collaborative problem solving through creativity in problem definition: Expanding the pie. Creativity and Innovation Management, 9(1), pp.54-76.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F., 1988. A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Dorst, K. and Cross, N., 2001. Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem–solution. Design studies, 22(5), pp.425-437.

Hall, E. (2013) Just enough research [ebook] New York: A book Apart

Jen, N. (2017) Natasha Jen: Design Thinking is Bullsh*t. 99U Conference June 7 – 9 2017 New York City

Jen, N. (2018) Natasha Jen: Design Thinking is Bullsh*t. Design Indaba Conference February 21 – 23 2018 Cape Town

de Mello Freire, K., 2017. From strategic planning to the designing of strategies: A change in favor of strategic design. strategic Design research Journal, 10(2), pp.91-96.

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M., 1973. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy sciences, 4(2), 155-169.

Ruhleder, K. and Star, S.L., 1996. Steps toward an ecology of infrastructure: design and access for large information spaces. Information Systems Research, 7(1), pp.111-134.

Smith, P.G. and Reinertsen, D.G., 1998. Developing products in half the time: new rules, new tools. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold

OHD_WRT_0121 the code/manifesto

The manifesto below is based off Meirle Laderman Ukeles’ Manifesto for Maintenance Art.

This the code of ethics outlined in by Mike Monterio in Ruined by Design. I am using this as a base for my code of ethics for this project. I have written a summary of each rule and then written in the green text how I might fulfil it.

A designer is first and foremost a human being.

Designers work within the social contract of life. Within their work they need to respect the globe and respect fellow humans. If their work relies on the inequalities in society they are failing as a human and a designer.

This project risks becoming a completely digital affair, which can be alienating to some in society, especially the elderly who make up the majority of this project’s audience. Another large responsibility is making this an eco friendly venture, which in my opinion is essential but not easy.

A designer is responsible for the work they put into the world.

The things designers make, impact people’s lives and have the potential to change society. If a designer creates in ignorance and does not fully consider the impact of their work, whatever damaged then is caused by their work is their responsibility. A designer’s work is their legacy and it will out live them.

This is where I think an oral history project about this project will encourage an awareness around the impact of the design. If one of the first things the archive designed houses is recordings of those would built it, it will show confidence in the work. The legacy of the project will live within the outcome of the project.

A designer values impact over form.

Design is not art. Art lives on fringes of society, design lives bang in the middle of the system of society. It does NOT live in a vacuum. Anything designed lives within this system and will impact it. No matter how pretty it is if it is designed to harm it is designed badly.

Nothing a totalitarian regime designs is well-designed because it has been designed by a totalitarian regime.

M. Monterio ‘The Ethics of Design’ in Ruined by Design

Let’s make it inclusive before we pick out the font. This is especially a rule for me, a former artists.

A designer owes the people who hire them not just their labor, but their counsel.

Designers are experts of their field. Designers do not just make things for customers, they also advise their customers. If the customer wants to create something that will damage the world it is the designer’s job as gatekeeper to stop them. Saying no is a design skill.

The team at the National Trust and the oral history department are (relatively) new to the world of design so it is my job to help them navigate this rather messy world.

A designer welcomes criticism.

Criticism is great. Designers should ask for criticism throughout the design process not only to improve the thing being designed but the designer’s future design process.

Now that I am working between three different parties it is essential that I keep communication open at all ends. The more the merrier attitude must reign.

A designer strives to know their audience.

A designer is a single person with a single life experience, so unless they are designing something solely for themselves they probably cannot fully comprehend complexity of the problems their audience is facing. Therefore it is designers’ responsibility to create a diverse design team, which the audience plays a big role in.

This collaborative project is perfectly set up the fulfil this, as long as COVID-19 does not get in the way.

A designer does not believe in edge cases.

‘Edge cases’ refers to people who the design is NOT target at and therefore cannot use. Designers need to make their design inclusive. Don’t be a dick.

The National Trust has a very particular audience which in some design projects would make them edge cases. In this project I think I need to look at how people with disabilities would use the archive and people who are not native to digital technology.

A designer is part of a professional community.

Each individual designer is an ambassador for the field. If one designer does a bad job then the client will trust the next designer they hire less. It also goes the same way, if a designer refuses to do a job on ethical grounds and then another designer comes along and happily completes the job, then the field becomes divide.

This collaboration between Northumbria University, Newcastle University and the National Trust has the potential to be the start of a series of collaborative projects. It is therefore my responsibility to ensure a positive working relationship with all involved. I need to be aware that I am an ambassador for all the institutions involved.

A designer welcomes a diverse and competitive field.

A designer needs to keep their ego in check and constantly make space for marginalised groups at the table. A designer needs to know when to shut up and listen.

I want to invite everyone to the party. Because the collaboration I have access to all the experts at the university but also at the National Trust. And each institution also has a huge and diverse group of people who can help influence and criticise the work. Think MDI and the volunteers at Seaton Delaval Hall.

A designer takes time for self-reflection.

Throwing away your ethics does not happen in one go, it happens slowly. Therefore constant self-reflection is essential. It needs to be built into each designer’s process.

I started doing this during MDI so now I can build on it. Maybe this website can help me reflect by holding all my thoughts. I should probably also timetable in moments of reflection from the off.