Tag Archives: Oral History

OHD_WRT_0273 The Trust: stories of the nation

With 1700 recordings of radio programmes, oral history interviews, and field recordings, how many stories lie waiting to be uncovered in the National Trust Sound Collection? In May and June 2023 I carried out an access and copyright audit on the National Trust collection held by the British Library. Although I was in search of signed agreements, I was gripped by the stories, the lived experiences, the contradictory emotions and opinions that are held in this collection. They tell the tales of one of the biggest charities in the country and of the country itself.

The most prominent story in the collection originates from a watershed moment in 1946, when institutions could finance the purchase of important cultural property for the nation through the National Land Fund. The National Trust in particular benefited from the scheme, which allowed the handing over of keys and grounds to the Trust instead of paying estate duty. The effects of the National Trust’s ever-expanding portfolio is covered in a song I came across performed on BBC Radio Four by Kit and the Widow in 1992. “Oh, the National Trust” is a satirical song from the perspective of two volunteers, who sing the tale of a Dowager Duchess of a nameless country house going mad as her home is flooded by National Trust visitors. Eventually the Dowager is sold at Christie’s after her harassment of the visitors becomes too much to bare and she needs to be removed from the property. The song ends with the Dowager’s revenge: she returns as a ghost to haunt her former home and the National Trust. The song neatly covers the stereotypes of the National Trust: the displeased landowner, the busy National Trust volunteers selling tea towels and Beatrice Potter books, and of course, a ghost, the natural partner of any self-respecting country house.

This turbulent period of transition from private ownership to a Trust property is both confirmed and challenged by the contents of other recordings. I found a local resident recalling being chased off a public footpath by an angry landowner, mirroring the Dowager Duchess’ antics. Then there is a former estate owner praising the National Trust taking over their houses because by the mid twentieth century: “the houses were falling down all around the place, nobody could see the future.” What prompted – or forced – owners to give up their home is not always covered in great depth: some interviewees mention death duties as the primary reason to offer their property to the National Trust; a desire to preserve ‘our country’s heritage’ crops up occasionally but seems less of a driver.

Kit and the Widow’s song does not mention an important personal consequence of the transition from private to public ownership: how does the change affect the many people employed on the estates? A significant portion of the interviews in the collection are with people who were former maids, gardeners, butlers, cook, valets, housekeepers etc. The collection therefore captures two elements of the transition story: how the land went from private to public property and how this signified the end of a particular ‘upstairs/downstairs’ system of employment.

Among the more ‘Downton Abbey’ tales in the collection there are interviews which record the role of many stately homes during the two world wars. There are interviews with those immediately affected: evacuees, prisoners of war, the land army, the home guard. Many other recordings reference the period. The government requisition of country houses during the wars is an important chapter in the history the nation’s country estates. Although the importance of this is often acknowledged, there is also a lamentation of the state in which the houses were often left. A gentleman points outs to an interviewer that the priceless wooden panelling is littered with holes, caused by the Land Army workers having their dart board there. The stately homes during this period were neither the grand houses of the wealthy owners nor the tourist attractions they are today: reduced to their basic structures, they functioned as prisons, barracks, and army training camps, where work and play all happened under one roof. Sadly, there are significantly fewer recordings with those directly involved in this period and why this is, remains unknown.

The collection shows how the role of the stately home and grand estate changed over the years but it is not just about people, communities, and social structures. The Director General at the time points out during a radio interview to commemorate the centenary of the National Trust in 1995 that the Trust is not just a ‘keeper of country house’, it actually spends most of its conservation effort on the landscape. Indeed, the National Trust is one of the biggest landowners in the country. They are responsible for landscape from the White Cliffs of Dover to the landscape around Stonehenge (although Stonehenge itself is English Heritage). The collection tells us clearly how our attitude to the land has evolved and how nature has changed as a result of human activity. A speaker recalls seeing the Northern Lights in the Clent Hills in the 1930s before light pollution drowned out the stars. Similarly, the relationship between farming and nature conservation is prominently present in the many interviews with farmers and recordings of Trust staff discussing their policies around farming and conservation. Deer hunting crops up time and again, which in the 1990s was still permitted. Folklore plays a prominent part too; the relationship between the land and tales of ancient witchcraft are plentiful. Yet, in spite of the Director General’s wish to turn the focus away from the National Trust as keepers of country houses, there are distinctly fewer recordings connected to the landscape than there are to country houses.

The National Trust stereotype of the Kit and the Widow song is undeniably a prominent part of the collection. However, when one considers this second biggest oral history collection in the British Library, it is difficult not to be impressed by the sheer scale of the institution. The National Trust is one of the biggest landowners and charities in the UK; the number of stories and histories which come under its care are innumerable. And these are exciting and often fundamentally conflicting stories: there is no single story of the National Trust. Recounting the history and significance of the Trust is always a balancing act in which the many layers of history kept by and embodied in the estates needs to be told from different perspectives. A conflict of interest and a struggle for prominence is present in the current collection, but certain questions that are in the public eye today are notably absent. Nobody asks where the money came from, for example. The colonial pasts of these properties appear absent although it would be an interesting research project to comb the archived recordings for references to colonial ties. And so, let me finish with another few suggestions of stories that could be told or investigated in this collection of cassette tapes and WAV files.

There are few recordings post-2000 so there is little discussion or mention of climate change and the effects it is having on the land, the housing and the Trust’s conservation efforts. Yet, is there evidence of changing nature? The stories and experiences of the National Trust volunteers, the corner stone of the National Trust’s work, are not prominent in the wider collection, but notably start appearing in the more recent recordings. Fundraising efforts is another topic that could be traced, for example, the owners throwing ‘medieval banquets’ as a way of making money. Seaton Delaval Hall, the National Trust property in the North East that I investigate as part of my PhD thesis, was well-known for their themed parties and banquets and many visitors to the property reminisce about the ‘wild nights’. Finally, the many interviews with gardeners and landscape architects are begging to be brought together to create a history of the Trust through gardens. After all, the National Trust tops the European charts for the number of gardens under its wings.

Clips

| Number | Content | Copyright |

| Recordings referenced in the blog post | ||

| C1168/648 | The song “Oh The National Trust” by Kit and the Widow | BBC Radio 4 |

| C1168/144 | Local resident talking about being chase off a public path by the Duchess of Wimpole Estate | No copyright |

| C1168/1605 | Someone talking about Clent Hills | No copyright |

| C1168/618 | Duke of Grafton talking about the National Trust saving the crumble country houses | No copyright (But was NT staff) |

| C1168/1001 | Land army girl at Sutton Hoo | Copyright |

| C1168/526 | NT Director General talking about the Centenary | BBC |

| C1168/819 | NT Director General talking about deer hunting | BBC Radio 2 |

| Recordings that have copyright and might be good for the blog post | ||

| C1168/621 | Coventry, 11th Lord (Family of property owner (before donation to National Trust)) | Copyright |

| C1168/849 | Cocking, Mary (Between Maid) | Copyright |

| C1168/914 | Drane, Jim (AWRE Technician) | Copyright |

| C1168/1108 | Evacuees | Copyright |

Possible Photos

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:National_Trust_Sign_271.JPG

OHD_PRS_0265 Reusing oral history in GLAM: a wicked problem

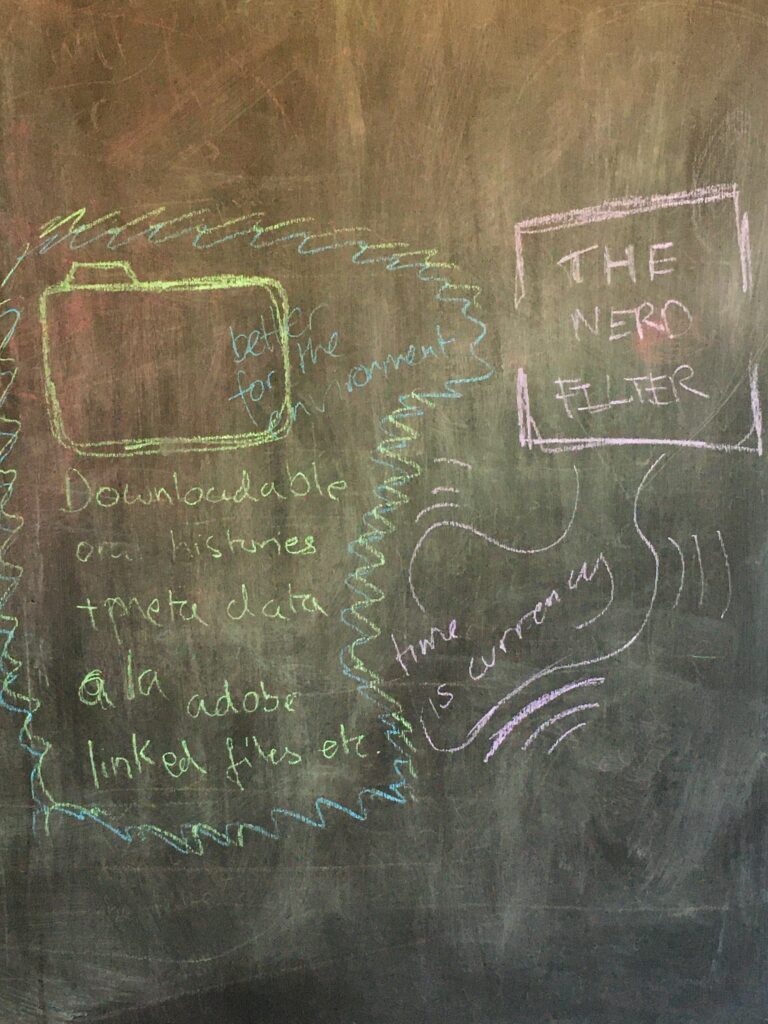

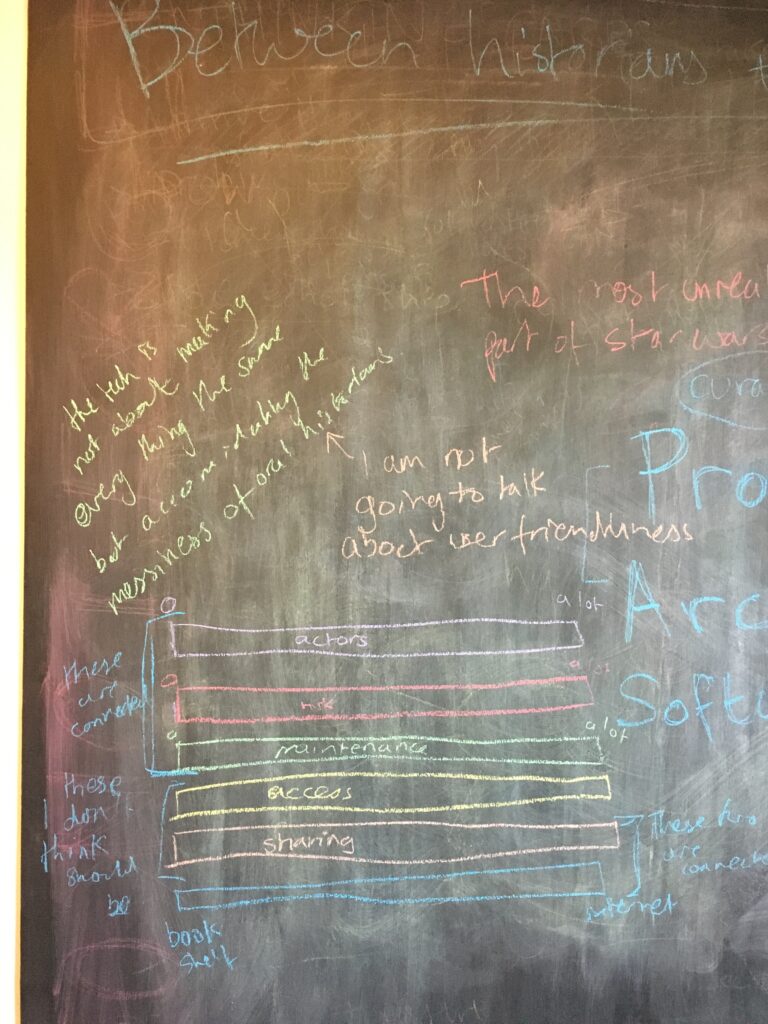

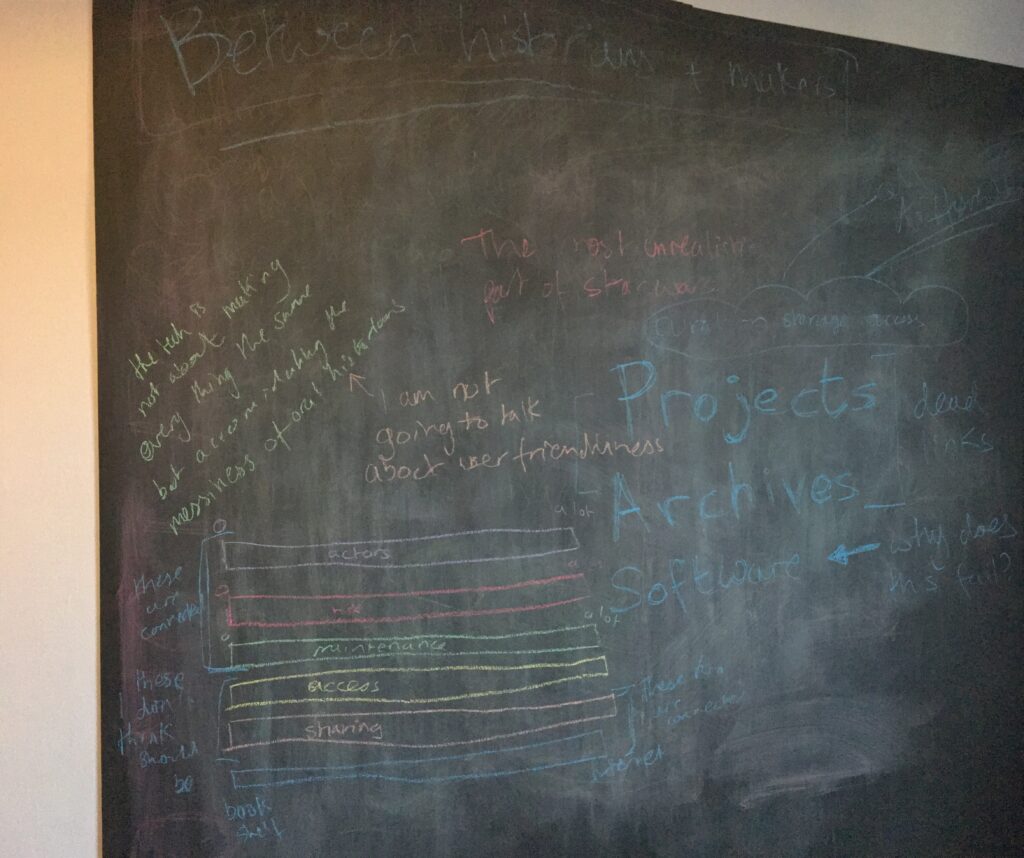

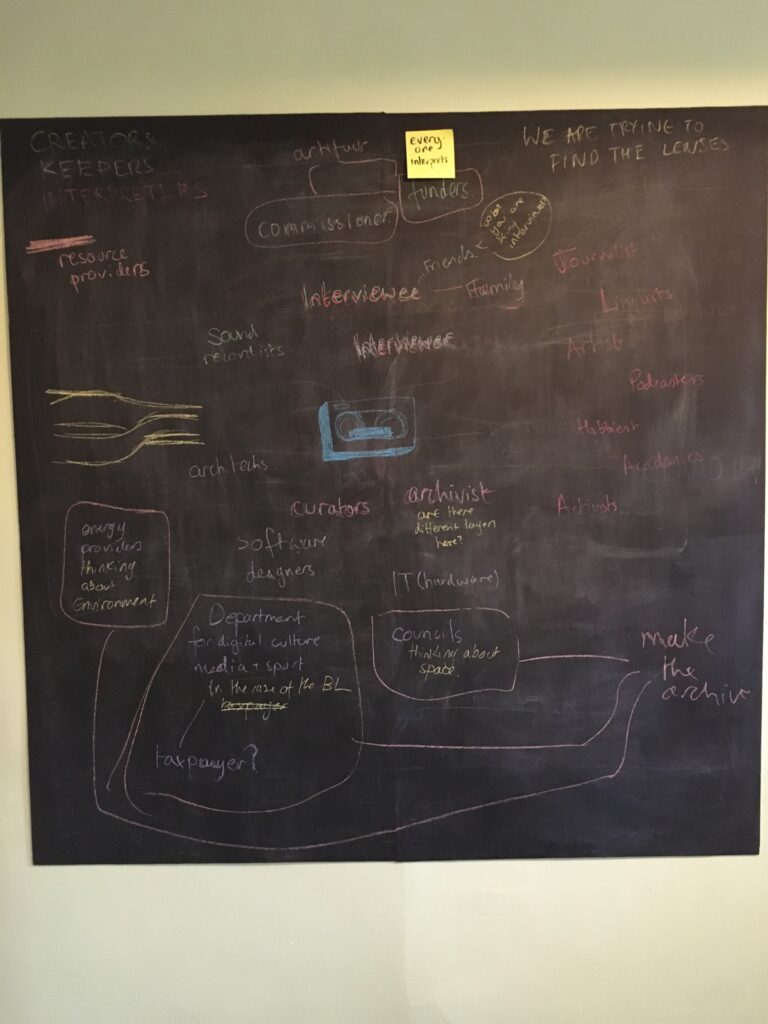

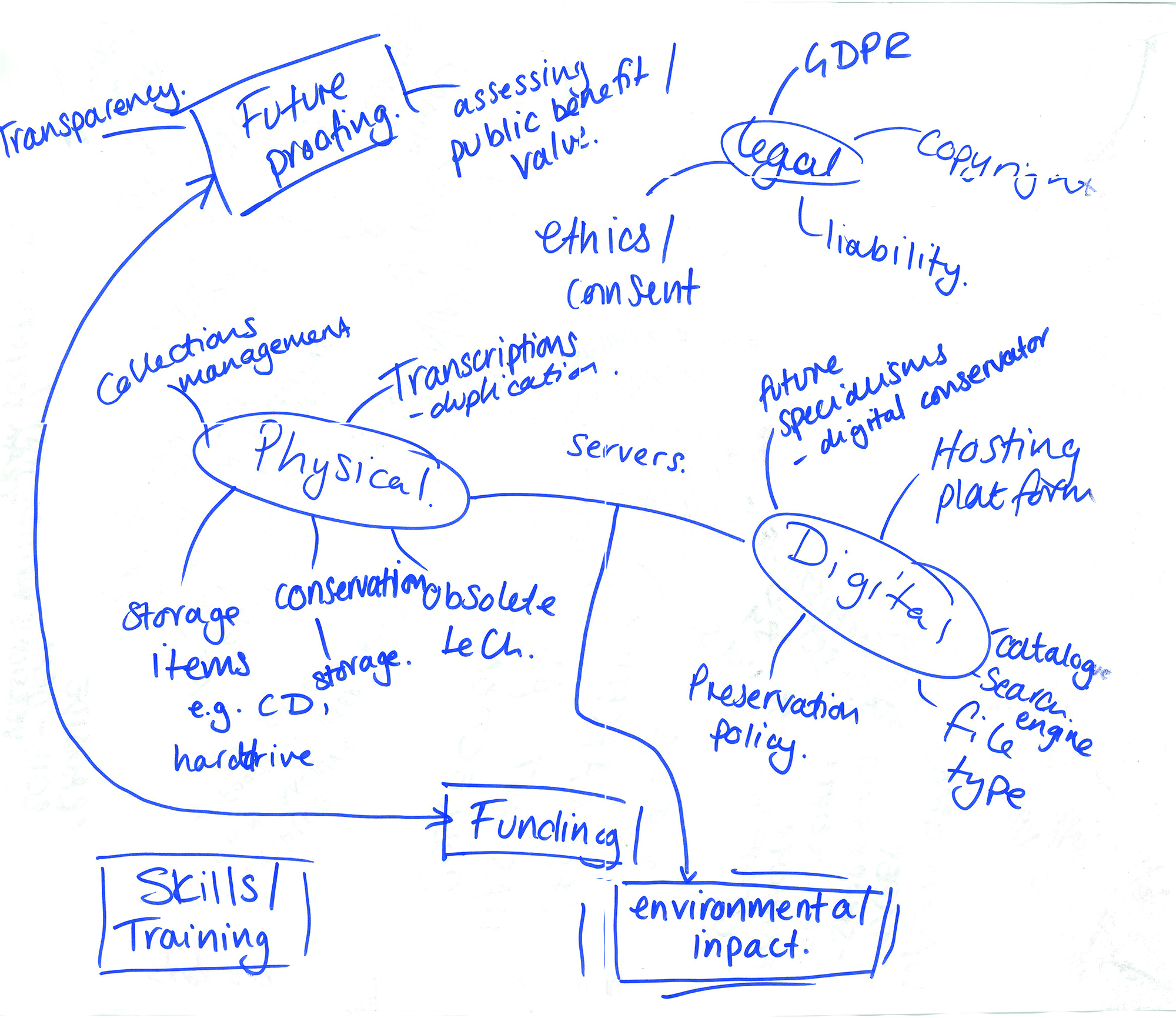

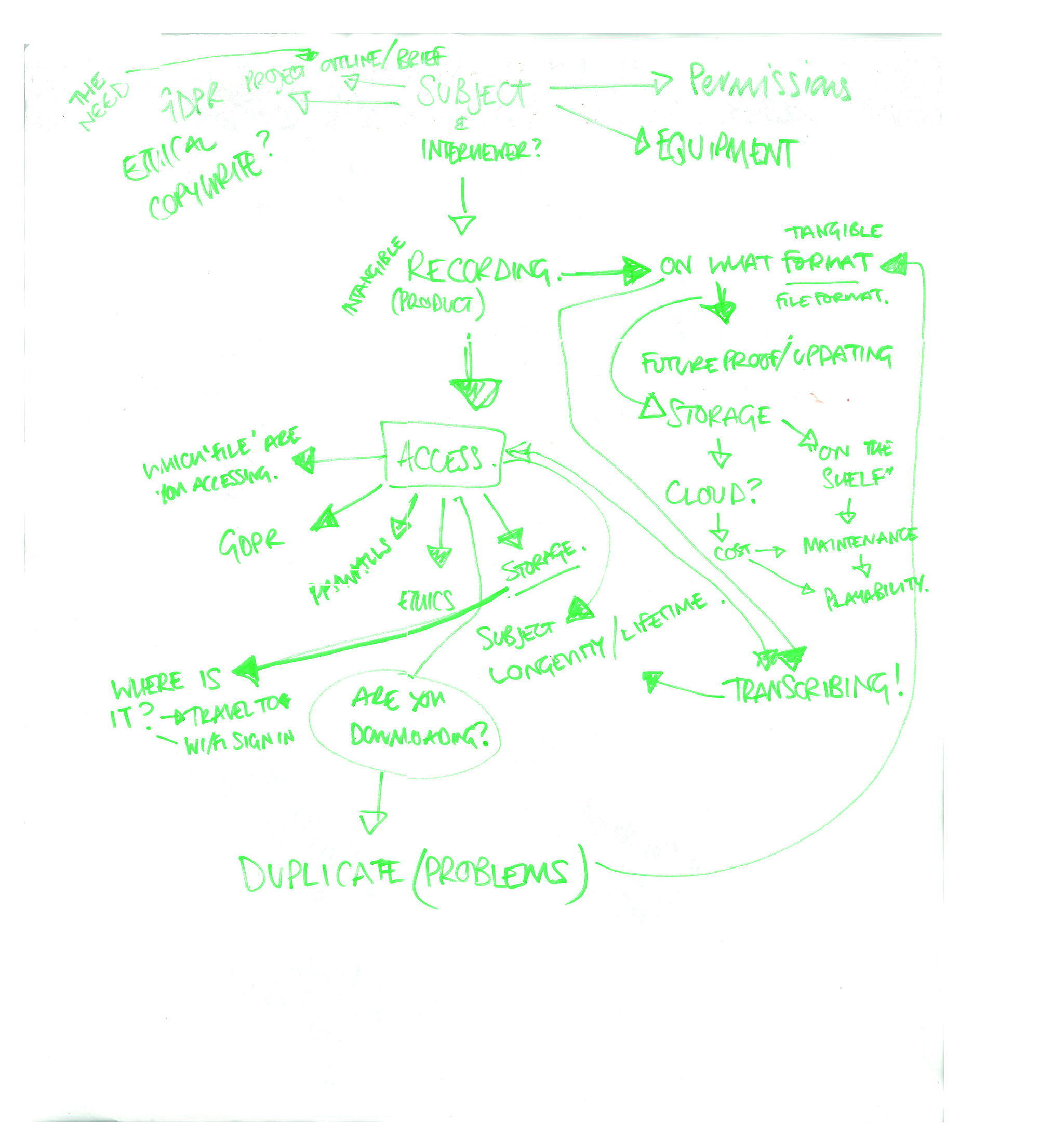

My PhD or CDA, collaborative doctoral award is about reusing oral history recordings within GLAM, galleries, libraries, archives, and museums. I am using the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall, as a case study. Now for context my background is in Art and Design. I did Fine Art at undergrad and then moved into design, specifically innovation and system design. And so when it comes to the infamous issue of reusing oral histories I approach it from the perspective of a designer. This has led me to frame the issue as a “wicked problem”. The term “Wicked problem” comes from a paper titled, Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, written by a Professor of the Science of Design, Horst Rittel and a Professor of City Planning Melvin Webber in 1973. And the term has been adopted by innovators and designers because this paper is about problem solving and the act of design is basically problem solving. In the paper Rittel and Webber specifically discuss two types of problem solving: “tame and benign” problems and “wicked problems”. Tame, benign or scientific problems are simple. They are easy to define and have one simple solution. It is a very linear process: define problem, solve problem. A wicked problem is exactly the opposite. They are extremely difficult to define and coming up with one simple solution is close to impossible. And the process of solving a wicked problem is not linear at all. Defining the problem and creating solutions often happen at the same time in a kind of back forth manner. You make an initial definition of your problem and create a solution to that problem and then the testing of a solution reveals another part of the problem. So you go back to your problem definition and tweak it, and then think of another solution and it repeats. In fact, as Rittel and Webber write this process could go on forever since a wicked problem will forever keep evolving as the world changes. You can therefore never truly solve a wicked problem but only pick various interim solutions which are not perfect but will cause the least damage. And to keep creating these interim solutions you need collaboration because a single person could not possibly understand all the evolutions in the wicked problem, all the different angles, all the different stakeholders.

Therefore my project is a Collaborative Doctoral Award for a really good reason. I have benefitted greatly from being in collaboration with the National Trust because I got access to a huge variety of people who I could work with in order to build a better understanding of the problem definition and any potential solutions. And over the nearly three years I have been working on this project I have been able to expand the definition of the oral history reuse in GLAM problem. It is extremely complicated, and the specifics of my case study will not be the same as all GLAM institutions. As trait seven of wicked problem goes “every wicked problem is essentially unique”. But I have found five recurring areas of wickedness, which most GLAM institutions will have to deal with when tackling the reuse of oral history recordings: technology, labour (specially maintenance labour), money, ethics and law, and value. In order for an organisation to start understanding the wicked problem of oral history reuse and start creating solution, there needs to be a collaboration between the people who work within these five areas. Within each unique institution there will definitely be other areas and other people that need to be brought to the table but it is these five areas and the people who work in them which make up the foundation of solving the wicked problem of oral history reuse.

I am going to start with technology because this is the area which often hogs all the attention, which is not surprising, we like the technological fix, it’s sci-fi, it’s the future, it’s a bit magic. But its magic is an illusion, as Willem Schneider acknowledges in his reflection on the oral history reuse technology Project Jukebox[1]. Technology on its own will not solve the wicked problem of oral history reuse. Obsolescence has be built into technology in a near aggressive way. So while you can recruit a software engineer at the start your project to develop your technology, you are going to need someone who is able to maintain the technology when obsolescence kicks in. The area of technology is therefore completely intertwined with the area of labour, specifically maintenance labour. Maintaining a technology is not easy and the more complex a technology, the harder it is the maintain, and the more specialised person you need to hire to maintain it.

So when we think about the technology we are going to use to tackle our wicked problem, we need to always be thinking about the labour needed to maintain it. We need to collaborate with those who will maintain it and not be seduced by magic of complex technology. Because while we now have complex AI technology like ChatGPT, I can tell you from experience, and I am sure many of you can relate, in the National Trust you are using a landline to organise interview dates and posting transcripts and consent forms by snail mail. As the historian David Edgerton writes in his book The Shock of the old we should not measure technology through innovations but rather use. In which case Excel and Word are still king of the technologies.

So the technology used to help create a solution to the wicked problem of oral history reuse has to be proportional to the skills of the person maintaining it, which is why you collaborate with them. But that person and their skills will need to be paid for and so you need to talk to the money people. Economic system you are working in will directly influence your technology, because the more complex the technology, the more expertise you need, the more likely it is things are going to be a little more on the expensive side. People with advanced technological skills are not cheep. They make a lot more money shooting down bugs all day in a monster tech organisation then being the IT person in the GLAM sector. And this is not just money for a set amount of time, this is labour needed to maintain an archival object – this goes on forever. So getting feedback from the money people on any solutions you are developing your solve your wicked problem, your particular case of “how do we make oral histories reusable within my institution?”, is invaluable because the truth is money does make the world go round. So recruiting them into your little collaboration crew is essential.

Now what I have talked about so far is basically the mechanics of oral history reuse. How you use an appropriate technology to get your oral history recording from A to B from a WAV file to useable, searchable interface and keep it there. But you cannot just simply just go from A to B with oral histories. I have done three different placements for my PhD and in during all of them I was trying to make archival material reusable. I spent those six months not thinking about technology but working on either copyright, data protection, or sensitivity checks. When you are working with oral histories you are dealing with people’s lives, permissions and restrictions have to be in place in order to make it available. Which is why alongside your tech developer, your maintainer, money people, you have to have your copyright team, your data protection team, and maybe some kind of ethical review team. And again, just like obsolescence in technology collaboration is crucial because ethics changes all the time. Copyright in the form we know it now was heavily influence by the internet, which is relatively young. GDPR was only implemented in 2018. And what language and images are deemed socially acceptable is always changing. The feedback you get from the ethics people to keep your ethics up to date is so important, because most institutions in the GLAM sector cannot really afford a lawsuit or scandal, so you need to get this right.

It is getting busy our collaboration crew but have one area of wickedness left, value, and this is where things start to get really sticky, because all I have talked about so far is about making reusable oral histories not about actually reusing them. You can lead a horse to water but you cannot make it drink. You can make your oral histories as reusable as you like but if people do not want to reuse oral histories they are not going to reuse, even if its easy to do. They have to see the value in reusing.

And this is where I mention trait 8 of wicked problems “Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem”. The difficulty of reusing oral histories is a symptom of the problem with how we value historical material. And how we value historical material is a wicked problem in itself because you can value things in so many different ways. The classic way is it monetary value. Within this frame oral histories are not going to fair to well against other historical items like chairs, paintings, original Beatles lyrics. In total I have seen the National Trust used eight different ways to value material:

Communal – The item represents a particular community.

Aesthetic importance – The item is deemed ‘aesthetically’ important or is from a famous artist.

Illustrative / historic – The item is illustrative of some historic moment.

Evidential – The item works as evidence to see how something was.

Supports Learning – The item is helpful in supporting learning found in the national curriculum.

Popular appeal – The item has mainstream appeal.

Cultural heritage significance – The item is significant to a specific culture.

Contextual Significance – The item gives important contextual information to a site, or a historical event

Materials also have international, national, regional or local value.

You can also flip the idea of value, how much is it going to cost to keep this item? This can again be measured several ways for example money and space, but also carbon. How much energy will it take to keep this item? Yep the reusing of oral history is an environmental issue.

Value is complicated and in order to get people to reuse oral histories we need to understand all the value oral histories can offer. We need to talk to curators, artists, educators, community workers, academics, all the potential different reusers and ask them what they find valuable. Why would they reuse oral history? And then we need to think about how we communicate this value. Do we go top down and work with policy makers to develop policy which makes it a requirement to reuse oral histories? Or do we work bottom up and try and nurture a culture of oral history reuse by teaching it more at a university level and creating projects based around reuse? Although whether a project based solely around reuse will get funding is another question, which brings us back to the money people and proves the wicked entanglement of it all.

This is not a banal, tame problem. It is a wicked problem – a mess. These five areas, well four overlapping` areas and a continent of complexity, are deeply intertwined and this is before we even start bringing in the unique elements of each individual institutions case of oral history reuse. And the only way to start detangling in some way without failing or being destructive is by collaborating and create a solution that will bring us a step closer to reusing oral history.

[1] “we stumbled onto digital technology for oral history under the false assumption that it would save us money and personnel in the long run.” (p. 19)

OHD_GRP_0260 Oral history at the National Trust Poster

OHD_PRS_0259 Learning from ourselves : Reusing institutional oral

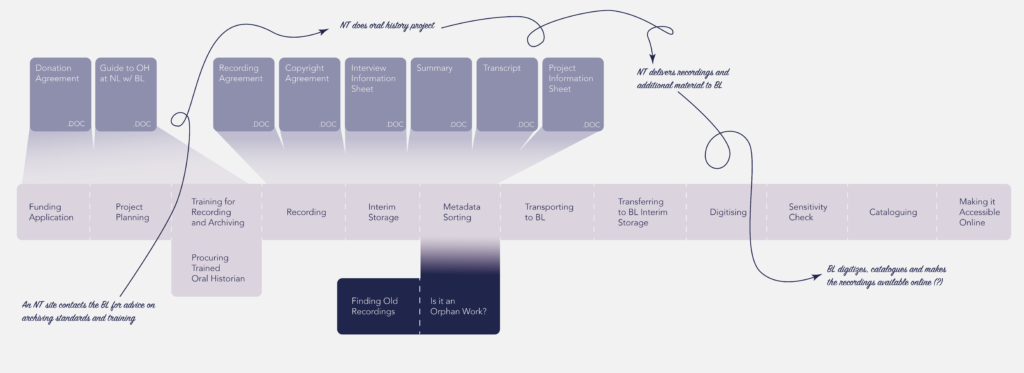

We would like to start by quickly introducing our projects, as we will be using them to illustrate our methodologies. My project is with Seaton Delaval Hall, which is a National Trust heritage site in the North East of England. The land has been in the hands of the Delaval family since 1066 after the Norman conquest. The hall now standing on that land was completed in 1728, it partially burnt down in 1822, was restored after the Second World War and was then given to the National Trust in 2009. The National Trust, set up in 1895, is one of the biggest heritage and conservation charities in the UK and also one of its largest landowners. In a review done in 2020 the National Trust revealed that Seaton Delaval Hall amongst many other properties had connections with the slave trade and other colonial activities. My PhD is looking into how we can reuse oral history recordings on heritage sites and how heritage sites can benefit from reusing oral history recordings beyond the usual collecting of stories.

My project is at the Archives at NCBS which is a collecting centre for the history of science in India situated at the National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bangalore. I want to study the processes of institutional policy making through the lens of gendered safety policies in scientific institutions. I hope to understand the various deliberations and considerations behind policy-making in different areas, through interviews with the stakeholders of institution policy – policy-makers, enforcers, students and staff. Some questions I hope to ask include specific concerns about safety that led to action from scientific institutions, how policy solutions were formulated, debated and enacted, the responses to these actions from persons on campus, and the corroboration and/or dissonance between anxieties of campus occupants and policy. I am aiming to learn more about gender discourses that informed policy, and the feedback to this discourse after their adoption into daily working.

The reason these projects have been brought together for this presentation is firstly due to convenience. We met at Archives at NCBS and then got talking about our projects, which revealed an overlap in our motives within our respective projects, which is reusing oral histories. In particular, we are approaching oral histories from the perspective of the archives. Moreover, while both of us are acting as independent observers, we are doing so on behalf of our respective institutions and our work is deeply embedded within them. Within this context – deeply tied to the institution and to the archive – we found that the “oral history project” format, i.e. recording oral history and then turning it into a book or exhibition, does not fit the rhythm of either. The institution and the archive aim to work in perpetuity, while the oral history project is often tied to a single moment, and is distinctly linear and terminal. The “oral history project” format simply does not accommodate what we wish to do with institutional memory. So we propose a new method of approaching oral history projects cyclically by recording with the explicit intention of reuse by a different individual at a later date, and reusing with the explicit intention of connecting oral history projects to the history of doing history in the institution. But before we explain our new method we need to understand oral history’s relationship with institutional memory, what it offers as a tool to capture or perhaps not capture when it comes to institutional memory.

In a 1986 paper on the use of history as an organisational resource, Omar El Sawy, Glenn Gomes and Manolete Gonzalez describe how institutional memory consists of semantic memory – or past learning that has been codified into procedures and processes – and episodic memory – defined by them as the unwritten memories within an organisation of a “repertoire of responses” to various situations that arise in the course of working, held as stories, myths, artefacts by individuals. Organisational or institutional memory – used interchangeably – is therefore defined as “…accumulated equity representing the beliefs and behaviours of organisational members both past and present cumulated over the life of the organisation”.

In our experience, archival records can allow us to trace the histories of policy deliberations. We can know when specific infrastructure, facilities, policies, and even laws were instituted. Through letters, meeting minutes, and personal records we may even find added context. What we lose is an implicit, often commonly understood discourse, that informs the creation and adoption of policies by members of the institution, based on different lived experiences inside and outside the institution over time – basically the intangible memory that El Sawy et. al. termed episodic.

On a basic level, oral histories work to simply fill gaps in knowledge in records – for instance, at NCBS in the OH catalogue, in an interview with an architect who worked on the construction of the campus, one finds reference to an on-site stone crusher to make jelly for construction that caused the interviewee lung problems due to fine debris. They state that this experience led to the removal of on-site crushers in all future constructions. The memory of this event has been institutionalised as a standard process, without there being a push to preserve the memory itself. Similarly, at Seaton Delaval Hall, through oral history interviews Hannah found information on various maintenance and conservation jobs that had been done over the decades which had not been formally documented. She also found how the management styles of the various general managers of the hall have affected the relationship between the staff and the volunteers. This is particularly important in the National Trust because the sites rely heavily on volunteers to run the sites.

But oral histories can also contain more abstract information. For instance, at Seaton Delaval Hall, the oral history interviews were able to capture historiography, so how people have talked about certain events over time. This is a possible helpful source to the running of heritage sites and how the staff might develop exhibitions and installations to either match or challenge people’s feelings around certain events or include material and stories which they prioritise or miss out. To give another example from the NCBS catalogue, several interviews refer to a sense of alienation felt between incoming students and the institution. These references can be found across students, faculty and staff, with differing personal explanations for this feeling from all quarters – whether it’s the question of open labs, the creation of departmental silos, or the changing priorities of the student body. This sort of documentation of ‘feeling’ is the unique advantage of oral history as a source – and gives vital information about the individual-institution relationship.

So we fully champion oral history interviews as a way to capture institutional memory, but we need to remember one of the very important traits of institutional memory, which is how it is distinctly dynamic in nature. In a 2020 monograph, James Corbett argues how institutional memory is more than a collection of facts and figures, and even recollections of events and contexts – it is a narrative about the institution’s wider identity. This narrative Corbett discusses comes from Charlotte Linde’s 2009 monograph, Working the Past: Narrative and Institutional Memory. In it she defines institutional memory as “representations of the past” brought into the present by individuals. Because of the nature of the workplace institutional memory is dynamic, because representations of the past change with the people representing it, the purposes for which narratives are created, and the changing circumstances and shape of the institution itself.

And this is where things start getting complicated, because as we established oral history is good at capturing institutional memory, but the format of the “oral history project” does not lend itself to preserving the dynamic nature of institutional memory. There are several reasons for this, the first being the well-known fact that no one reuses oral history recordings, it is in Michael Frisch’s words “the deep dark secret of oral history”. In reality this is not a secret but more like the very large bright pink elephant in the room no one wants to talk about. Oral history recordings rarely get reused when an oral history project ends, which is not why we record oral histories. One of the reasons we wish to record is because they capture the “missing” parts of history, which are important for an institution to reflect on its current trajectory. An example of an oral history project which focused on recording institutional memory but suffered the same fate as every other project was done by the United Nations. The UN did an oral history project titled The United Nations Intellectual History Project or UNIHP to investigate the history of ideas with the UN. It followed a similar format to any other oral history project with the knowledge found in the oral histories published into a several volume book series. Oral history itself is neither finite nor final, and projects like UNIHP – i.e. terminal project that ends by creating a heavy bulk of static knowledge – build in redundancy by attempting to codify it without factoring in the inherent changeability of narratives in an operative institution. In a paper on UNIHP the reader is pointed toward a website www.unhistory.org, which now will bring you to a Japanese holding website. A further search only turns up a handful of articles and references to the book series. There is no evidence of the recordings being easily accessible today. Historians, like Portelli have discussed a long-time impulse to turn oral history into a written transcript before use, as a way to make such interviews an objective source – but we have far moved past the point where the legitimacy of oral history was in question. Our continued attachment to text-based outcomes has done injustice to the new possibilities offered by oral history.

Within our project we wanted to use oral history to capture institutional memory but the oral history project format misses the dynamism of memory which is so valuable to our understanding of the history of institutions. So we offer an alternative. Instead of the somewhat linear method of recording, making something, likely text-based, from those recordings and then leaving it in an archive to gather dust, we propose a continuous cycle between recording and reusing. In this cycle you record with the primary aim for it to be reused further down the line by someone else and you reuse with the aim to record new material based on what you found in the archived recordings. We believe this cycle can achieve a more integrated culture of oral history instead of having the occasional oral history project. We will take you through the stages more specifically with Hannah discussing how she has recorded oral histories with aim of reuse and then looking at how Soumya reused oral histories with the aim of recording.

Record for reuse

For my project with Seaton Delaval Hall I specifically approached my recording with the question – what will the people who will be reusing want from this? Of course there is no way to really know what they would want in the future. So instead of directly answering the question, I decided to get a better understanding of the community surrounding the hall, their hopes and dreams, and also make sure they knew about my work and what I have to offer by recording oral histories. How I did this materialised in two ways: integrating into the hall’s community and leaving behind as much of my findings as possible.

I started off simple when integrating into the hall’s community by volunteering as a room guide. I then also did a three month placement where I helped them set up an onsite research room. When it came to recruiting for my oral history project I nearly always had the staff help me find candidates and I have always been transparent about who I am recording. I also started to ask the staff if they had any questions they would like put to the interviewees or whether they were looking to find out something about the history of the hall or the maintenance of the hall. For example, the gardener wanted to know the exact date the rose garden was planted which the old caretaker of the property could answer. I also have been able to work out the location of the old kitchen garden by recording people who had been at the property during the Second World War. I am not suggesting they would not have been able to find this information anywhere else but asking a human is often faster than searching through piles of archival material. I have also been able to capture the various ideas people had for raising money for the hall. These ideas could be helpful for any other property wishing to raise money if they wanted to know what worked and what did not. I hope that by being more visible and collaborating with the staff I make the value of oral history more visible and prove to them how it can help them in their work.

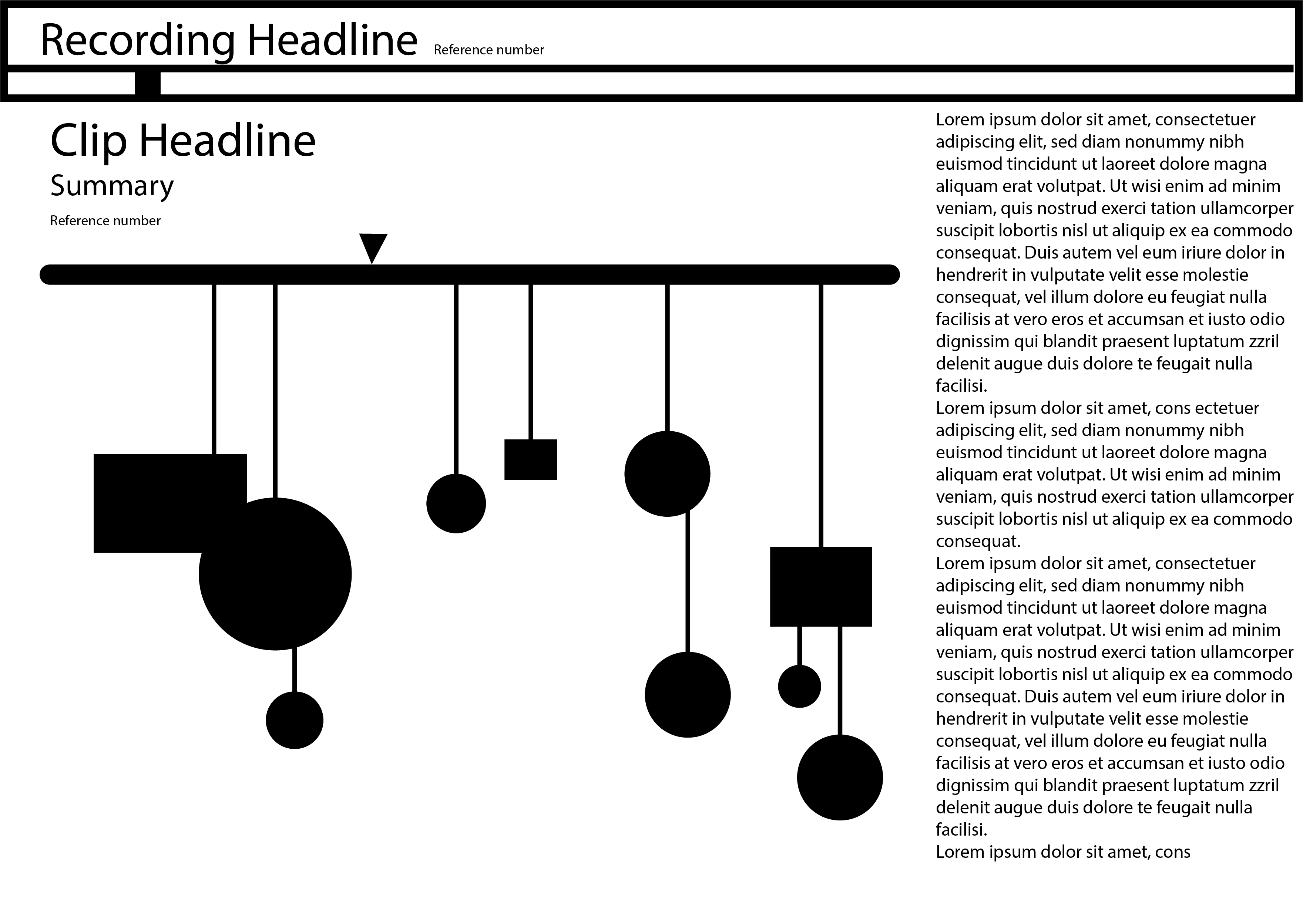

The second way I am trying to help the people who would be reusing my oral histories is by making sure I leave behind as much information in addition to the recording.This is important because the structure and nature of heritage organisations means there is a lot of staff rotation. Each new staff member has to relearn the history of the hall and neither them nor I will have the time to chat about all what can be found in the oral histories I have recorded. I therefore need to create a document that helps them navigate the oral histories and seek out their value, without it being a hefty transcript. I made a spreadsheet, because nearly everyone can open these on their devices.

On one sheet we have the oral history recordings breakdown, where I have given a summary of the whole recording, but also broken the recording down into sections I believe might be relevant, because interviews can be studied in the context of a number of themes, which we miss out on if we only stick to the objective of an individual, time-bound project. In addition I gave each section a value tag. The value tags come partially from me, historiography, institutional knowledge, and stories, and also from how the National Trust assigns value to their collection items. These value tags will obviously also change over time, as we alter our perception of what is valuable. This means we are continuously capturing our perception of value within the archive and the institution. In addition, the spreadsheet also contains a sheet with a recruitment plan so anyone is able to continue recording oral histories if they wish to do so. What I wanted to achieve with this spreadsheet is to make an easily searchable document that encourages people to go and listen to the recordings, while also allowing them to easily add and edit the entries if necessary. I believe my insistence on integrating into the Seaton Delaval Hall community and leaving behind as much information as possible besides the recording should help heritage sites integrate oral history into their day-to-day instead of having the occasional “oral history project”.

Reuse for recording

To reiterate, my project – on the history of gendered policy making in scientific institutions – began in the course of my internship as an archivist at the Archives at NCBS, which also entailed learning the methodology of oral history interviews. After talking to our artist-in-residence at the time about women’s safety on campus, I became interested in recording oral histories on the topic. I started exploring secondary sources as background work for my project, and found myself relying on past oral history interviews, which made me realise the importance of not creating in a vacuum when it comes to studying institutional memory, eventually culminating in my discussions with Hannah around reusing oral histories.

The plan for the project was initially to record life story interviews with a list of people across various informal interest groups on campus, and across scientific institutions in Bangalore. As with any other project documenting institutional history, my first step was to explore secondary sources. I found the work of Abha Sur, who had discussed CV Raman’s treatment of the women in his lab; and Deepika Sarma, who while writing for the magazine Connect, had explored women’s experience as later entrants into IISc. Both these projects used archival records in combination with oral history interviews they were conducting. I also went to 13 Ways, an exhibition from 2017 put up by the Archives at NCBS, which had a section dealing with gender. 13 Ways was a narrative born out of a catalogue of more than 60 oral history interviews, as well as 600+ archival objects. Having referred to these secondary sources, due diligence required that I track down the primary source, and I was able to gain access to the summaries of the oral history interviews done at NCBS – though not the actual recordings. The oral history interviews had been recorded to document the history of NCBS in 2016. These interviews include both life story interviews and interviews specific to the involvement of individuals with the construction of campus.

Oral histories have a unique usefulness in histories of gender given the absence of gender in archival records – and in the beginning I was only reusing oral history projects insofar as they bridged this gap of information. But navigating the catalogue as I was planning out my project helped me realise the methodological value of intentional reuse for the purposes of studying institutional memory.

In planning out my interviews, I could not sidestep the problem that in asking direct questions about gender, I would be providing my interviewees a lens through which to view their lives. This was especially problematic as gender is not a neutral lens, especially in the field of science. I’m under no illusions about the subjectivity of oral histories, and the value of documenting narratives regardless. From having read Sur and Sarma’s work, I had realised, however, that my project had a different objective, because I was trying to study gender in the institution over time, instead of how it played out in one specific individual’s life, or one specific moment of time. My project combined gender and institutional history, and as we have established, the study of institutional memory is a collation of individual narratives. I worried that any conclusions I would draw from my interviews would be so fixed within the specific gender discourse of the present, that I would be left with very little scope for generalisation beyond individual experience.

Reusing oral histories from a past project helps me in three ways:

Firstly, I was able to find discussions of gender from people who either were completely absent from the archives, or who were generally believed to be unconnected to the issue, for instance, discussions on gender with canteen and security staff. Often overlooked in the processes of decision-making, their involvement in everyday activities on campus as subjects, observers, enactors, and in some cases enforcers, contained reflections on campus culture and power hierarchies that is completely missing from archival record. This led me to include a wider demographic in my interview plans.

Secondly, reusing oral histories lets me understand the events in the past that may or may not have shaped my interviewee’s present perceptions of the issue of gender – which will enable me to ask questions about events instead of themes in my interviews.

The oral history interviews contained information about undocumented events that were well-known on campus which I would have had no idea to even ask about – such as references to a protest and awareness/information campaign against sexual harassment in the immediate neighbourhood of campus by students, a recounting of efforts from students to formally organise into a gender collective that had fallen through, and even additional context around the institution of a shuttle service for people who walked home. In several cases, past interviews recorded the perspectives of persons who are now inaccessible. This kind of background knowledge has helped me plan out interviews such that I have some control and intentionality in where I bring in the specific lens of gender. It will let me ask questions about lived experiences without always having to guide the interviewee towards my theme. In other words it lets me talk about gender without asking about gender. This has the additional benefit of making my interviews more viable for reuse by future researchers, feeding into the cycle of recording and reusing we are proposing.

Finally, reusing the past catalogue allowed me to see the same events and themes discussed from a completely different vantage point, which will let me find patterns in my data and past data in comparison. This will hopefully allow me to construct generalisable knowledge for the institution. Gender exists within the scope of institutional memory, and therefore it is a dynamic and perpetually reshaped discourse. By providing a historiography of gender discourse, reusing past oral history interviews lets me subvert the inherent temporality of interviews to methodologically meet the requirements of studying institutional memory. Simply put, by resisting the urge to create in a vacuum, and locating my project in a continuum of other such projects, I, and researchers who study the institution after me, are better equipped to study the evolution of memory in an institution rather than its instance in a specific moment.

Conclusion

To quickly summarise, oral history is an excellent way to capture institutional memory because it captures the feelings and networks which are not held in archival documents, which motivated us to do our respective projects. However, the format of the oral history project freezes institutional memory into a rather unnatural state since by its nature institutional memory is forever changing and evolving together with the people who make up the organisation, especially as we are dealing with organisations that are still operational. Using our experience of recording and reusing oral history we have been able to explore an alternative to the usual oral history project format. We proposed that when you record oral histories you take in consideration the potential for reuse and so put in labour to make the recordings more accessible for future researchers who could be exploring a variety of themes. We also suggest that when beginning the process of recording oral histories to study institutions, researchers refer back to previous oral history projects and sources to enrich their own understanding and provide deeper and more complex context for their individual themes and lines of questioning. These two approaches, for us, allow us to rethink the concept of oral histories within institutions in a way which makes the process of studying them reiterative, and so complements the dynamic nature of memory in an operating institution, such that we are able to use the methodology of oral histories to its fullest extent.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Sources:

- El Sawy, O. A., Gomes, G. M., & Gonzalez, M. V., 1986. Preserving Institutional Memory: The Management of History as an Organizational Resource. Academy of Management Proceedings, 1986(1), 118–122. doi:10.5465/ambpp.1986.4980227

- Emmerij, L., 2005, June. The History of Ideas: An Introduction to the United Nations Intellectual History Project. In Forum for Development Studies (Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 9-20). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Frisch, M., 2008. “Three Dimensions and More” in Handbook of Emergent Methods, p.221.

- Huxtable, S. et al., 2020. Interim Report on the Connections between Colonialism and Properties now in the Care of the National Trust, Including Links with Historic Slavery. National Trust: Swindon

- Linde, C., 2009. Working the Past: Narrative and Institutional Memory. United Kingdom: OUP USA.

- National Trust., 2023. Seaton Delaval Hall. [Website]. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/north-east/seaton-delaval-hall

- Portelli, A., 2009. What Makes Oral History Different. In: Giudice, L.D. (eds) Oral History, Oral Culture, and Italian Americans. Italian and Italian American Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230101395_2

- Sarma, D. 2021, June 21.Women and the Institute. Connect. https://connect.iisc.ac.in/2018/06/women-and-the-institute/

- Srinivasan, V., 2017. 13 Ways [Exhibition]. Archives at NCBS, Bengaluru, India. http://stories.archives.ncbs.res.in/exhibit/13ways/

- Summaries of oral history interviews, Oral history collection at Archives at NCBS. http://catalogue.archives.ncbs.res.in/repositories/2/resources/14

- Sur, A., 2001. Dispersed Radiance Women Scientists in C. V. Raman’s Laboratory. Meridians, 1(2), 95–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40338457

- Weiss, T.G. and Carayannis, T., 2005, June. Ideas matter: voices from the United Nations. In Forum for Development Studies (Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 243-274). Taylor & Francis Group.

OHD_RPT_0256 Options for making oral histories accessible

Tech options for making oral history recordings accessible

V1. January 30 2023

Hannah James Louwerse, Archives at NCBS

Making oral history recordings accessible to people has been infamously difficult, with the oral historian Michael Frisch referring to the issue as “oral history’s deep dark secret”. There have been many attempts to solve this problem with some being more successful than others. By analysing the history of oral history technologies one can see how using technology to access to oral history recordings depends on three factors: maintenance, ethics, and user-friendliness. This short report will go through each of these factors bringing examples of oral history technologies to explain what you should look for when seeking a solution to putting oral history recordings online.

- Maintenance

Maintenance is often the biggest killer of solutions to the deep dark secret of oral history. Maintenance depends on a continuous supply of money and labour, which is not always easy to get hold of, especially within grant cycles. It is therefore essential to think about the maintenance necessary to sustain a technology which allows access to oral history recordings. How you do this depends on the source of the technology and how it was developed.

- Tailor-made, in house development and maintenance

Creating your own digital oral history archiving system allows it to be perfectly tailor to your collections needs. However, it also means the maintenance of this system is solely in your hands, which can be very risky, especially when working within grant cycles. Projects like the Visual Oral/Aural History Archive (VOAHA) created by Sherna Berger Gluck at California State University, Long Beach and Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database developed by Doug Boyd built tailor-made technologies specifically for their existing oral history collections, either developing the technology themselves or hired someone to do it for them. At the time they were the height of technology, but when the money ran out there was none left to maintain the archives/databases. Both VOAHA and Boyd’s Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database were “digitally abandoned” and left vulnerable to inevitable technical obsolescence and online hackers (Boyd and Larson, 2014, p. 7; Boyd, 2014, p. 90). In the end the two projects were absorbed by their respective universities’ libraries.

1.2 Use existing specialist oral history software

By using specialist oral history software, the maintenance is no longer your responsibility, which is both a risk and a benefit. The benefit is how it is a cheaper option in comparison to hiring someone full time to take care of the technology. But the risk is that the software developer stops maintaining the software, which is what happen in the case of Stories Matter, an oral history software developed by the Centre of Oral History and Digital Storytelling at Concordia University and a software engineer from Kamicode software (High, 2010; Jessee, Zembrycki, and High, 2011). The Kamicode website still has a page on Stories Matter, but the software is not downloadable. The reason for this is unclear, however it is easy to imagine the maintaining of such niche software is unlikely to be a high priority for a software company.

A more successful example of specialist oral history software is Oral History Metadata Synchronizer (OHMS), developed by Doug Boyd after his reflections on Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database. OHMS has been in existence for some years and is a popular way for oral history projects and archives to organise their oral history metadata and link the video/audio file to a searchable text. Unlike Stories Matter, OHMS is developed and maintained by people who are interested in oral history and use it for their own projects. Maintaining OHMS is therefore in their own interest.

1.3 Use existing mainstream third party platforms

Another cheaper option is using more mainstream platforms such as Soundcloud or Spotify. These are less niche technologies and therefore do not have the benefits more specialised software has, but the maintenance is pretty much guaranteed since these platforms are universally used. Certain projects have created Spotify playlists and other have Soundcloud versions of their recordings alongside the original files in the brick-and-mortar archive.

- Ethics

The internet is an ethical nightmare and putting someone’s personal story online in an ethical manner is not an easy task. The starting point will always be clear communication to the interviewees on how people will be able to access their recording, and thorough paperwork which accompanies the recording. Following this there are a couple of other things people have done to support the ethical handling of oral history recordings.

2.1 Extracts

The simplest of ethical practices is to only make certain extracts available online. This means you can avoid putting online more sensitive information but still give an example to the archive visitor of the kind of content the oral history holds. If the archive visitor wishes to hear more, they can request the full recording via email. A possible consequence of this might be people only using the online extract and not bother enquiring any further because it is deemed as “too much effort.”

2.2 End user agreement

Archives like Trove and Centre for Brooklyn History have “end user agreements” the archive visitor must agree to before they are allowed access to the oral history recording. These end user agreements contain information on basic copyright and data rights, a disclaimer about the opinions expressed in the recording, and outline the archive user’s obligations. These obligations include correctly citing the recording, adhering copyright law and data protection law. These end user agreements are a way for archives to hold users accountable in case of misuse or rights violations.

- User-friendliness

People have a low tolerance of bad user-experience design. The software Interclipper, championed by Michael Frisch was reviewed during the development of Stories Matter and VOAHA and was deemed difficult to use in both instances (Jessee, Zembrycki, and High, 2011; Gluck, 2014). It no longer exists. OHMS offers both a backend metadata synchronizer and a viewer, the latter however is often left in favour of an in-house interface design. Project Jukebox developed by the University of Alaska in collaboration with Apple Computers Inc. in the 1990s, is still available online but still looks like it was made in the 90s, even though at the time it was described as “a fantastic jump into space age technology” (Lake, 1991, p. 30). It is therefore important the user experience and interface are updated as fashions and taste evolve across the wider internet.

List of examples

- Project Jukebox: https://jukebox.uaf.edu/

- Stories Matter: https://www.kamicode.com/en/portfolio/project/23-concordia-university-stories-matter

- VOAHA: https://csulb-dspace.calstate.edu/handle/10211.3/206609

- Civil Rights Movement in Kentucky Oral History Project Digital Media Database: https://crdl.galileo.usg.edu/collections/crminky/?Welcome

- OHMS: https://www.oralhistoryonline.org/

- Soundcloud: https://soundcloud.com/balticarchive

- Spotify: https://anchor.fm/RainhamHall

- Trove: https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-220064352/listen

- Centre for Brooklyn History: https://oralhistory.brooklynhistory.org/interviews/rivera-dolores-19920911/

Bibliography

Boyd, D.A. (2014) ““I Just Want to Click on It to Listen”: Oral History Archives, Orality, and Usability” in Oral History and Digital Humanities. pp. 77-96. Palgrave Macmillan: New York

Boyd, D.A. and Larson, M. (2014) “Introduction” in Oral History and Digital Humanities. pp. 1-16. Palgrave Macmillan: New York

Gluck, S.B. (2014) “Why do we call it oral history? Refocusing on orality/aurality in the digital age” in Oral History and Digital Humanities. pp. 35-52. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

High, S. (2010) “Telling stories: A reflection on oral history and new media” in Oral History. 38(1), pp.101-112

Jessee, E., Zembrzycki, S. and High, S. (2011) “Stories Matter: Conceptual challenges in the development of oral history database building software” In Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 12(1)

Lake, G.L. (1991) “Project Jukebox: An Innovative Way to Access and Preserve Oral History Records” in Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists. 9(1), pp.24-41

Smith, S. (Oct 1991) “Project Jukebox: ‘We Are Digitizing Our Oral History Collection… and We’re Including a Database.’” at The Church Conference: Finding Our Way in the Communication Age. pp. 16 – 24. Anchorage, AK

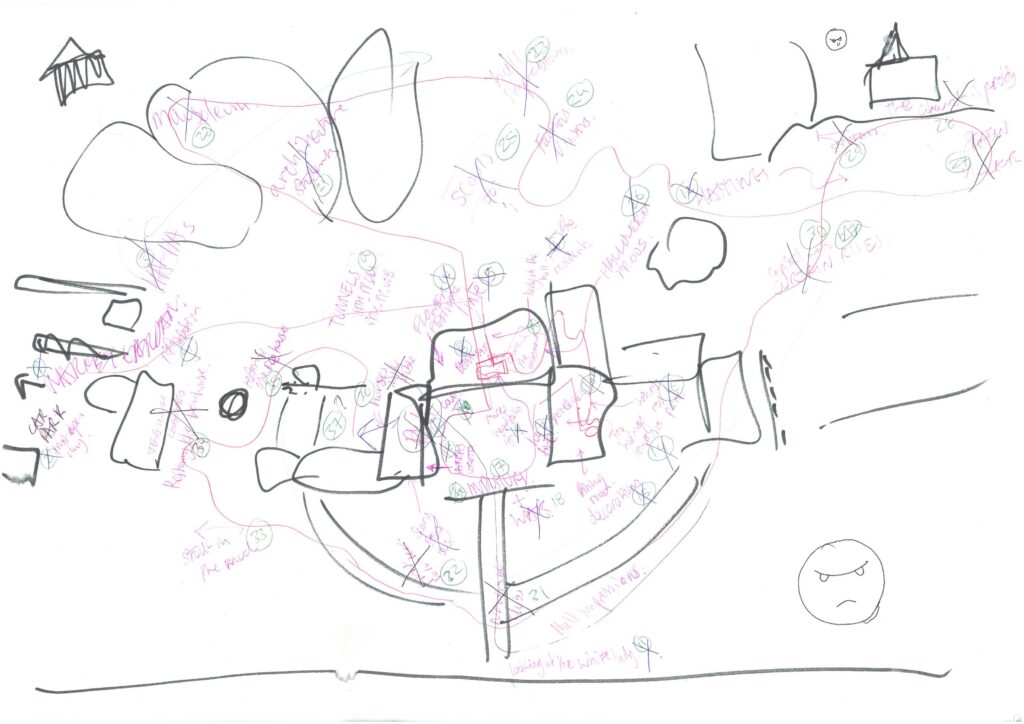

OHD_WHB_0246 Miro board of NCBS placement

OHD_DSF_0240 Heritage Surrogates after climate disaster

Hello welcome. My name is Hannah and today I want to take you through a couple fo examples of how our surrogates collection has helped us recreate heritage in times of great loss.

Just for those who do not know our surrogate collection is a collection of metadata that describes a material object or site and its context. The data in the surrogate collection is groups of information like, photographs, measurements, scans of maps, descriptions, and even oral history recordings. Our initial motivation to collect this information was because certain items we were interested in would come up for auction and in some cases we would be unable to acquire it and it would end up in a private collection. The thought was that if we had enough surrogate information and this information was store a safe and secure location we might be able to recreate certain objects if we needed to. The later also started to include items that were being treated by decay or mould or we simply could no longer look after properly because of budget cuts. After storm Humboldt which significantly damage the collection of a property in the south and the lost of cliff house a year later the institute decided to up the surrogate collection policy by getting sites to actively think about which collection items might be at risk and then even more ambitious act of creating surrogates for whole sites in some cases. This also led to an increase in oral histories being recorded as part of the surrogate scheme.

Moving on to our examples…

My first example is this bench which is a replica of a bench that was burnt during a fire caused by a severe drought we had a couple of years ago. The file on this bench in the surrogate collection had a couple of photographs but most importantly it had an oral history and some literature from the person who made the bench because they used particular techniques that are not very common knowledge.

The second development is one of our more recent project, which comes from the surrogate file on Seaton Sluice. The village no longer exists because after significant storms throughout the late 2020s it was deemed a unsafe space to live. At the time we collected maps, oral histories and photographs.

For the anniversary of the final resident leaving the village we commissioned a group of artists to create an audio visual experience to give an impression of Seaton Sluice before we lost it. We sifted through the surrogate data, the maps, photographs and recordings, and did a public call out for anyone who might have any material linked to the village, which led us to record new oral histories.

From this material two visual artists and sound artist created this beautiful map of Seaton Sluice which visually showed the different eras of the village and then on the map you had links to different audio clips. These audio varied between soundscapes, music and oral histories often mixing them together. In addition because we had so much archival material we also a creative writing student make a collection of short stories about Seaton Sluice, this was an extra thing visitors could buy. This project only week live a week ago so we have not yet had time to gather or evaluate feedback.

My last example it probably our most successful application of the surrogate collection, our local history storytellers. This does what it says on the tin. Storytellers go round visiting pubs, village halls and schools etc. telling stories of the local history. These stories are specifically about things in our surrogate collections because these are the things people do not have access to via museums or archives. We found that the surrogate collection is not used a lot by the public, so we wanted to do develop something that is a little more accessible and ended up with the storytellers. They have been great success. We are in our second year now and we have ten different storytelling programmes around the country and we are currently looking to add two new locations. People have said about the storytellers that they find it very engaging way to tell history and many have also commented on the pleasantness of the evenings and find them very relaxing. The schools similarly enjoy the storytellers. One of my favourite quotes came from Thomas, at St Mary’s Primary School saying, “I was going to go dressed up as Harry Potter for Book Day but now I am definitely going to go as Johnny the stable boy.”

So these are just three examples of what we are currently doing with our surrogate collection but we have many more in the pipeline and hope that we are able to do more as people become more aware of the collection and its potentail.

OHD_DSF_0238 Oral history project retention table

| Title of item | Item type | Brief Description | Retention Condition |

| SDH_PP_001_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Part of the Research Group. Some memory of the hall before the National Trust. | File to be kept for 25 years and then destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 25 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 15 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_002_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall staff member. Discusses the COVID-19 pandemic and the Curtain Rises restoration project. | File to be kept for 30 years and then destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 15 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_003_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of previous resident of Seaton Delaval Hall. Lived at the hall from 1947 to 2018. | File to be kept for 40 years and then destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_004_AUDIO | WAV | Auto-oral history recording of PhD student memories of Seaton Delaval Hall. The student is the interviewer in the other SDH_PP recordings. | File to be kept for 20 years and then transcribed and the audio is destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 20 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 10 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_005_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Possibly the first National Trust volunteer. Discusses the fundraising for acquisition and the hall before the National Trust. | File to be kept for 20 years and then destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 20 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 10 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_006_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Discusses the fundraising for acquisition and the hall before the National Trust. Also mentions activist work in local surrounding villages. | File to be kept for 25 years and then destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 25 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 15 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_007_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of a person who lived in Seaton Delaval during the war and remembers walking past the Seaton Delaval Hall to Seaton Sluice. | File to be kept for 20 years and then transcribed and the audio is destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 20 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 10 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_008_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of a person who did a variety of jobs at Seaton Delaval Hall both before and after the National Trust this included working in the market garden and architectural jobs. | File to be kept for 30 years and then transcribed and the audio is destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 15 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_009_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of the eight vicar of the Seaton Delaval parish telling tales of the Church of Our Lady on the Seaton Delaval Hall property. | File to be kept for 40 years and then transcribed and the audio is destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_010_AUDIO | WAV | Oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Discusses a lot of the fundraising for acquisition and research into the hall. | File to be kept for 20 years and then transcribed and the audio is destroyed. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than five times OR use in a publication, exhibition or similar within the 20 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 10 years and then reviewed. |

| SDH_PP_001_TRANSCRIPT | Transcript of oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Part of the Research Group. Some memory of the hall before the National Trust. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_002_TRANSCRIPT | Transcript of oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall staff member. Discusses the COVID-19 pandemic and the Curtain Rises restoration project. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_003_TRANSCRIPT | Transcript of oral history recording of previous resident of Seaton Delaval Hall. Lived at the hall from 1947 to 2018. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_004_SUMMARY | Summary of auto-oral history recording of PhD student memories of Seaton Delaval Hall. The student is the interviewer in the other SDH_PP recordings. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_005_TRANSCRIPT | Transcript of oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Possibly the first National Trust volunteer. Discusses the fundraising for acquisition and the hall before the National Trust. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_006_TRANSCRIPT | Transcript of oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Discusses the fundraising for acquisition and the hall before the National Trust. Also mentions activist work in local surrounding villages. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_007_SUMMARY | Summary of oral history recording of a person who lived in Seaton Delaval during the war and remembers walking past the Seaton Delaval Hall to Seaton Sluice. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_008_SUMMARY | Summary of oral history recording of a person who did a variety of jobs at Seaton Delaval Hall both before and after the National Trust this included working in the market garden and architectural jobs. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_009_SUMMARY | Summary of oral history recording of the eight vicar of the Seaton Delaval parish telling tales of the Church of Our Lady on the Seaton Delaval Hall property. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_010_SUMMARY | Summary of oral history recording of Seaton Delaval Hall volunteer. Discusses a lot of the fundraising for acquisition and research into the hall. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_METADATA | Spreadsheet of the SDH_PP oral history recordings’ metadata, includes interview length, location, equipment, and tags. | File to be kept for 30 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 30 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. | |

| SDH_PP_PROJECT_SUMMARY | Document by the SDH_PP interview on the project. Includes a brief summary on process and their reflection on the project. | File to be kept for 40 years and then printed off. UNLESS accessed and listened to more than ten times within the 40 year retention period. If so retention is extended by another 20 years and then reviewed. |

OHD_WHB_0228 OHT dissection

OHD_DSN_0225 The first draft design of the Seaton Delaval Hall sound walk

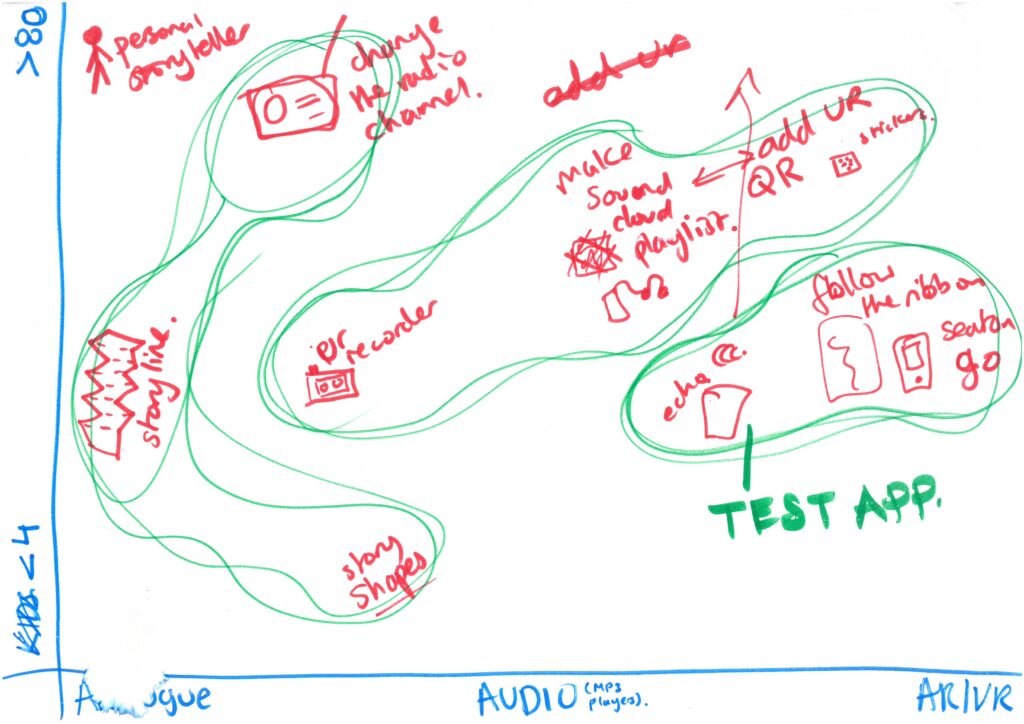

OHD_DSF_0224 A graph mapping fictional designs

OHD_DSN_0222 Interface

OHD_PHO_0209 Network and relationship

OHD_WKS_0208 NT Oral History Workshop

The overal aim of this workshop is to understand the value of oral history to heritage sites and understand the resources needed to safely store and exhibit these oral histories

Activity One: Oral History Braindump

Aim: To understand the value of oral history to heritage sites.

Task: To start with the participants will be asked to “dump” all the times they have listen to an oral history good or bad. They will then pick out the positive or negative feelings they had while experiencing these oral histories in an effort to understand the value of listening to oral history.

Activity Two: Breaking down an oral history recording

Aim: To understand what we need to do to make and keep an oral history recordin

Task: First, the participants will be asked to think about is needed to make an oral history recording. Then they will be asked what is necessary to keep an oral history recording.

Activity Three: What are we going to make?

Aim: To come up with ideas for the use of oral history by drawing on the two previous activities

Task: The participants are asked to come up with ideas that best display the value of oral history but also consider the resources, labour and ethics that are involved with handling an oral history.

Activity three was never completed

OHD_PRT_0199 Prototype for the Seaton Delaval Hall Oral History Trail

OHD_PRS_0185 Presentation for Jo and Heather

OHD_DSF_0184 Oral history at the hall design project

OHD_DSF_0183 Intangible and Digital Heritage Consultant

Intangible and Digital Heritage Consultant

The National Trust looks after one of the world’s largest and most significant collections of art and heritage objects set within their historic context. As ideas around heritage change enveloping not only the tangible but intangible heritage. We realise our duty of care extends beyond objects to the non-physical heritage such as folklore, traditions, and language that make our sights so unique. In addition we recognise the increasing amount of born digital material that will one day become the heritage of the future. We are therefore looking for a person to help us collect, manage, and curate the intangible and digital heritage of our sites in the region.

We expect this person to be experienced in collecting, managing and curating intangible heritage such as oral histories and be confident in their digital skills.

What it’s like to work here

The National Trust Consultancy is home to specialists in every field of our work. It’s a place where resources are shared across disciplines and boundaries, and it’s a great repository of skills, talent and experience. The diversity and quality of expertise within the Consultancy enable our properties and places to benefit from creative and innovative thinking, as well as deep expertise in all matters relating to our twin purpose of caring for the nation’s heritage and landscapes and making these accessible to all. The Intangible and Digital Heritage Consultant role sits within the Consultancy.

What you’ll be doing

You will be advising sites on their collecting and managing of intangible and digital heritage, supporting them during their intangible heritage projects and organising the collection of object metadata for surrogate collections. You will work between regional IT and the sites to ensure the needs of sites are considered, while simultaneously ensuring IT is able to keep a secure and stable digital infrastructure. You will also manage relationships with third party archives, to help guarantee access to material for staff and volunteers.

You will also provide tactical and strategic advice to the sites on how move modern opperation files to the archive, while also ensuring sites adhere to the National Trust policies around climate friendly storage.

Who we’re looking for

- excellent communications skills: verbal, written and presenting

- developing and delivering an internal communication (or similar) strategy and plan

- proven experience of communicating appropriately with a wide range of colleagues in different roles

- being a brilliant networker and influencer

- great project management skills, ideally including some experience of event management

- extensive experience of successfully managing diverse and varied workloads with tight timeframes and budgets

- being an excellent multi-tasker and self-starter

- excellent IT skills, including a good working knowledge of Microsoft, Sharepoint

Update meeting on Intangible and Digital heritage at Seaton Delaval Hall

26/09/2028

13:00

Seaton Delaval Hall

Participants

General Manager

Regional Curator

Project Lead

Intangible and Digital Heritage Consultant

Agenda

Introduction

Status Update

Discussion Topic 1: Dialect dictionary

Discussion Topic 2: Auction Items

Decision 1: Film Archive

Agenda for next meeting

Summary

Everything is ready to go with Storyland. Three institutional oral history recordings taken. Student project for a dialect dictionary is on track. Possibly will lose out on Garden Painting at Auction but metadata collected. Need to revisit somethings in Film Archive arrangement.

- Institutional Oral History

- Interview done with retiring cafe staff member

- Interview done with Gardening volunteer and Research group volunteer

- Possible follow up needed for gardening volunteer

- Not got copyright yet from research group volunteer

- Need to organise Oral history sessions with recent student project

- Storyland

- Everything is ready for 1st October

- Food trucks have been booked

- Storyteller was asking for some extra tickets

- Dialect dictionary

- Student has managed to get funding for archive visits

- Need to grant access to on site oral history recordings

- Need to find illustrator

- Rainham used a good illustrator

- Auction items

- Mahogany chairs

- Photographer has been arranged

- Curator says likely to win chairs

- Garden Painting

- Unlikely to win

- Meta-data already been collected

- Mahogany chairs

- Film Archive

- IT very enthusiastic

- Do we want to donate all material?

- Unsure about footage taken by volunteer

- Another meeting with General manager and Intangible and Digital Heritage Consultant

- Agenda for next meeting

- Update on Film archive

- Oral history interviews with students secured

- Progress on Dialect Dictionary

- Summer project 2029

- Adaptive release plan

Decisions

| Decision | Notes |

| Dialect Dictionary Illustrator | Using the illustrator Rainham |

| Donating (some) items to Film Archive | Definitely happy to donate some material but unsure about some footage take by volunteer. |

Actions

| Action | Person | Deadline |

| Contact students for Oral History interview | Project Lead | Within the next three months |

| Check with interviewer of gardening volunteer if they think another interview is required | General Manager | As soon as possible |

| Send extra tickets to storyteller | Project Lead | By the end of the week |

| Talk to volunteer about archiving film footage | General Manager | Before meeting with film archive |

| Arrange another meeting with film archive | Intangible and Digital Heritage Consultant | Within a month |