Tag Archives: Process

OHD_SSH_0294 Screenshot of email

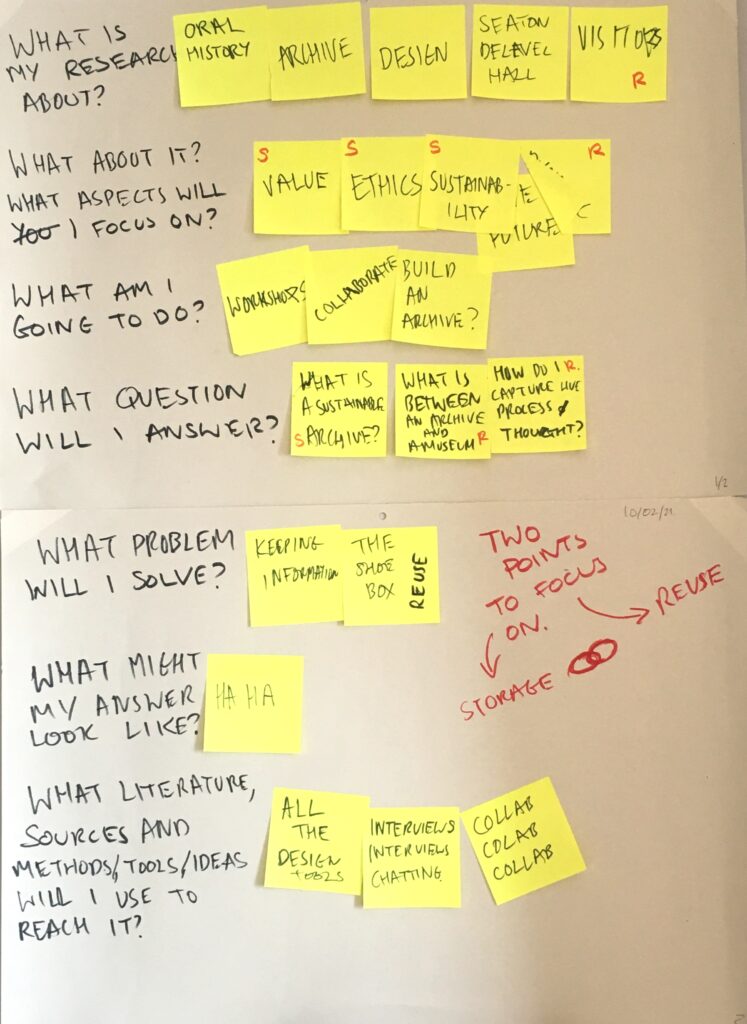

OHD_COL_0267 Photographs of PhD by Practice brainstorm

OHD_FRM_0253 Notice and takedown request review

OHD_FRM_0252 Takedown request form

OHD_RPT_0250 NCBS sensitivity check doc

OHD_RPT_0249 NCBS Takedown and alterations policy

OHD_WRT_0264 Why a PhD by Practice

Design is not an island

Every week or so I spend three hours standing in an 18th century hall. No one has asked me to do this, not my university or the hall, which is the partner institution within my Collaborative Doctoral Award. And yet, I do this because it is an essential part of my research. It is essential because the central issue of my research project is looking to solve the problem of the so-called “deep dark secret of oral history;” the sad reality that oral history recordings rarely get used once archived (Frisch, 2008). My work is specifically looking at how oral history recordings can be reused on heritage sites. This is not an easy problem to solve, in fact it is not an easy problem to define. It is what is referred to in the design world as a “wicked problem”, an extremely complex and ever-changing problem, which can be viewed from different perspectives, conjuring up different solutions (Rittel and Webber, 1973; Buchanan, 1992). In design the defining of a wicked problem and the testing of solutions happens simultaneously (Buchanan, 1992; Bailey et al., 2019). During this process the designer, the one creating solutions, needs to be deeply reflective. In the context of this project I play the role of the designer. My PhD is a PhD by Practice and standing in a hall is part of my process to define the problem and find a solution to the issue of the limited reuse of oral history recordings. This but a brief explanation to why I am standing in a hall, so let us take a couple of steps back to fully unpack why I am doing a PhD by Practice. We must start by understanding what a “wicked problem” is and where it came from, then we can look at the methods used to define and solve these wicked problems.

The rise of the swampy lowlands

We start around the middle of the Cold War, where there a significant “anti-professionals” movement underway and the professionals in question are going through a crisis of confidence. The term “professionals” is used by Horst W. J. Rittel, who coined the term “wicked problem”, and the philosopher Donald A. Schön, who wrote The Reflective Practitioner, to refer to practice based subjects which often quite some form of formal training, such as lawyers, doctors, engineers, police, and teachers. (Schön, 2016, p. 3; Rittel and Webber, 1972, p. 155). Neither Rittel or Schön discuss designers specifically, however designers would fall under the same umbrella as many designers first go to design school before they moved into practice. It was these professionals, who were going through a crisis in confidence because it seemed they were struggling to solve many of society’s problems. Rittel and Webber list the various areas where the public were becoming dissatisfied with the professionals work such as; the education system, urban development, the police. The issue which comes up in both Rittel and Webber’s piece and Schön’s book is the Vietnam War which was as Schön describes “a professionally conceived and managed war [which] has been widely perceived as a national disaster.” (Schön, 2016, p. 4). All these events and issues demonstrated to the public how the actions of professionals can have negative and even devastating consequences for differents groups of people in different ways (Schön, 2016, p. 4). Both Rittel and Webber, and Schön attribute the negative consequences of professionals’ actions to a mismatch between the society’s problems and the professionals’ approach to solving these problems (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 156; Schön, 2016, p.14). In particular it was their nineteenth century “Newtonian” and “Positivists” approach to problem solving, which no longer seemed to work on these twentieth century problems. Their approach was distinctly linear; define problem and then solve it (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 156; Schön, 2016, p. 39; Buchanan, 1992, p. 15). And while this approach works well when solving a mathematical problem or deciding a move in chess, it does not work when solving complicated problems. For example with the Vietnam war this linear approach resulted in the problem being simplified into “stop the spread of Communism” and the solution being reduced to “fight war with communists using chemical weapons”. We all know this did not work and the Vietnam War went on to become one of the biggest disasters in American military history. The war and other events made people think the professionals were no longer suitable to solve society’s problems, however Rittel and Webber and Schön argue this was due to their linear approach to problem solving not their lack of knowledge.

Rittel and Webber seem to at first attribute failures of linear problem solving to problems like the Vietnam War being simply harder to solve than the “definable, understandable and consensual” problems the professionals were working with straight after the Second World War (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 156). This would imply the problems dealt with after the Second World War were simple, like a mathematical equation. Although possible, we must also consider how there instead was a shift in how we view of problems and the structure of society as a whole, especially when we contemplate how philosophical schools of thought, such as Post-structuralism, were being developed around the same as Rittel and Webber were writing. While neither Rittel and Webber or Schön make direct references to the Post-structulaist movement, there are parallels between Rittel and Webber’s ideas and language, and the ideas and language found in the literature of the Post-structuralist movement. For example, in A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia published in 1980, the philosopher Gilles Deleuze and the psychoanalyst Félix Guattari they outlined the idea of rhizomatic thought, i.e. the idea that everything is connected through complex non-linear networks, rather than some form of linear hierarchy. Deleuze and Guattari’s idea of the Rhizome, and Rittel and Webber’s idea of the “wicked problem” are both proposed in opposition to the more Positivists and Newtonian linear way of thinking about society (Buchanan, 1999, p. 15; Deleuze and Guattari, 2004, p. 7). There are similarities in the language Rittel and Webber, and Schön used to describe these complex problems and the language Deleuze and Guattari used to communicate the nature of the Rhizome. For example, Rittel and Webber explain why they specifically use the term “wicked”:

We use the term “wicked” in a meaning akin to that of “malignant” (in contrast to “benign”) or “vicious” (like a circle) or “tricky” (like a leprechaun) or “aggressive” (like a lion, in contrast to the docility of a lamb). (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 160)

Along similar lines Schön refers to these problems as a “tangled web” or “a swampy lowland where situations are confusing “messes”” (Schön, 2016, p. 42). While Deleuze and Guattari write how “A rhizome [ceaselessly] establishes connections between semiotic chains, organisations of power, and circumstances” and talk about a rhizome’s complete lack of unity (Deleuze and Guattari, 2004, p. 8).

While conscious or not of the parallels between their ideas and the Post-Structuralist’s, it is Rittel and Webber, and Schön’s application of these Post-structuralist(-like) ideas which it useful to designers and other problem solvers, and became a corner stone idea of design thinking (Buchanan, 1992). They used the ideas of webs, networks and relationships to adjust two elements of problem solving: the overal aim of the process and the order in which things are done. Rittel and Webber, and Schön all write how within the old linear method of problem solving the main aim was to come up with a solution, and therefore less time was spent defining the problem. They wished to shift this focus to make the defining of the problem equal to (if not more important) than creating a solution (Schön, 2016, p. 40; Rittel and Webber, 1973). In addition, Rittel and Webber, and Schön all wished to abandon the idea of these linear steps in problem solving and instead have the problem definition and problem solution occur simultaneously, having each inform developments in the other (Buchanan, 1999. p. 15; Schön, 2016, p. 40). It is this latter change they propose which needs some further explanation to see why simultaneous problem definition and problem solution is vital to solving problems and untangling these wicked messes.

Understanding the web

Before we dive head first into simultaneous problem definition and problem solution we need to understand the structure of problems and why this makes them difficult to define. The wicked problem is one of many ways to describes complex problems, however there are other metaphors we can draw on. Near the end of the twentieth century you have the metaphor of “infrastructures” used by sociologist Susan Leigh Star to describe human relationships with technology and computer networks (Star, 1999), and designers have use the idea of designs living within wider eco systems to articulate the environmental impact of design products (Manzini and Cullars, 1992; Tonkinwise, 2014). All of these work as metaphors to help us understand the structure of the problems society is dealing with, and so to avoid confusion I will from now on just used the term “problem structure” and not wicked problem or rhizome or infrastructure or swampy mess. While problem structures are able to go by many names, there are four main traits problem structures have which are found across these different texts .

1. Problems are subjective

Since the linear format of problem solving spent little time on defining the problem/understanding the problem structure, it also did not consider the subjective nature of problem definition. The more Post-structulaist way of thinking about problems recognises how subjective our view of a problem structure can be (Rittel and Webber, 1972, p. 161). The problem structure is not a single person’s view on an issue but a collection of many people’s collective experience of an issue woven together into a web-like or, as Deleuze and Guattari would call it, rhizomatic structure. The sociologist Susan Leigh Star uses the example of a flight of stairs to illustrate the subjective nature of issues. A flight of stairs is to the majority of people a path from upstairs to downstairs or vice versa, however for a person in a wheelchair stairs are seen as as obstacle (Star, 1999, p. 380). You can expand this even further to cleaners finding stairs more difficult to clean than a flat surface or an architect wishing for a certain aesthetic style in the stairs or the builder who has to construct and later maintain the stairs or the person who has to source and pay for the materials used to make the stairs. Every single one of these views on stairs can be brought together to create the rhizomatic understanding of the stairs. By recognising the problem structure is made up of these subjective experiences the person tasked with problem solving is able to get a better understanding of the problem structure, ensuring they do not generate a solution based on a single narrative.

2. Problems are part of other problems

However, the borders of the problem structure do not end with people’s view and experience of the central issue you were looking at, as Rittel and Webber say “Every wicked problem can be considered to be a symptom of another problem”. Problem solving will start on one level, “crime on the street is a problem” and then move to higher levels, for example a general lack of opportunity, high poverty, or moral decay (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 165). This is similar to one of the properties of Leigh Star’s idea of infrastructure – “embeddedness,” which describes how an “infrastructure is sunk into and inside of other structures, social arrangements, and technologies” (Star, 1999, p. 381). A problem should therefore not be seen as an isolated issue but something connected and part of various other issues within wider society.

3. Problems are do not stand still

Problem structures are not static and will change over time. Deleuze and Guattari describe how “a rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines.” (Deleuze and Guattari, 2004, p.10). Within the context of problem solving this shattering and restarting means a problem structure is always evolving, which in turn means a solution offered at one time may no longer be appropriate further down the line.

These first three traits of problem structures are why solving problems without proper problem definition can be destructive. To start with problem solving is already inherently a destructive act. The design theorist Cameron Tonkinwise explains how “innovation is itself a deliberate act of destroying some aspect of current existence” (Tonkinwise, 2014, p. 201). Through problem solving the current existence is remoulded, new things are added and other things are taken away until a new order of things has been achieved (Tonkinwise, 2014, p. 201; Papanek, 2020, p. 3). It is sometimes necessary to destroy things, but when this destruction does not take into consideration the wider problem structure of the central issue the destruction can have ripple effects across the entire structure. It is therefore essential to identify the structure you are creating in and knowing to some degree what effect any intervention might have across the entire structure. As Rittel and Webber say:

It becomes morally objectionable for the planner to treat a wicked problem as though it were a tame one, or to tame a wicked problem prematurely, or to refuse to recognize the inherent wickedness of social problems. (Rittel and Webber, 1972, p. 161)

The destructive nature of problem solving means one needs to be extremely cautious. Knowing exactly what to propose, create, or design is key and it depends on your knowledge of the problem. And this is where the fourth trait of problems comes in, and when things start to get very tricky.

4. Problems are invisible

Parts of problem structures are invisible because they only become visible through some form of articulation. For example, with the first and second trait, problems are subjective and part of other problems, you are only able to see the parts of the problem structure you have researched through either observation or articulation from either yourself or someone else. If you do not talk to all the people involved there will be parts of the problem structure which is missing. Sometimes this is not you fault as Leigh Star points out centre topics “tend to be squirrelled away in semi-private settings” (Star, 1999, p. 378). Or you simple ran out of time, money, or patience before you could uncover the problem structure (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 162). When it comes to the third trait, problems do not stand still, there are parts of the problem’s network which do not yet exist and are therefore invisible.

There are also parts of the problem structure which are invisible unless under two circumstances, breakdown and probing. The first, Leigh Star lists as one of the properties of infrastructures, “invisible unless broken”. What Leigh Star specifically refers to here is types of maintenance structures, which society assumes will always work until they do not (Star, 1999, p. 382). Stephen Graham and Nigel Thrift in, Out of order: Understanding repair and maintenance, describe this phenomenon as follow:

The sudden absence of infrastructural flow creates visibility, just as the continued, normalized use of infrastructures creates a deep taken-for-grantedness and invisibility. (Graham and Thrift, 2007, p. 8)

Any breakdown of a problem structure could reveal elements of the structure which were previously invisible. The other circumstance when elements of the problem structure becomes visible is when is it probed. This specific action of probing in order to make visible is the main motivation to do problem definition and problem solution simultaneously (Rittel and Webber, 1973, p. 161). In their paper Rittel and Webber demostate this process on the “poverty problem”, where they first ask question “Does poverty mean low income?” and then work out what the determinants are for low-income through further questioning and answering (Rittel and Webber, 1972, p. 161). Every question is part of problem definition and every answer is part of problem solution, but both help build the problem structure. Each question is a probe which provokes an answer which makes visible more of the problem structure. Probes can take on different formats which I will expand on in the following section.

To summarise the four main traits of a problem structure are how it is: a collection of subjective narratives, connected to other problems, and always changing, and then an overarching fourth trait of general invisibility unless broken or probed. Recognising these four traits of a problem structure lays the foundation of simultaneous problem definiton and solution. can help in both problem definition and problem solution. The next step is to start building the problem structure and maybe find some .

The practical bit

Schön wanted to make clear the crisis in confidence professionals were experiencing during the Cold War and the anti-professional movement was due to the application of professional knowledge not the knowledge itself (Schön, 2016, p. 49). The linear method of problem solving did not allow for the complexity found in (modern) problem structures. However, Schön offers an alternative method which can handle the complexity of problem structures – “knowing-in-action.” Knowing-in-action is that tacit knowledge we gain from doing things and has the following properties:

- There are actions, recognitions, and judgements which we know how to carry out spontaneously; we do not have to think about them prior to or during their performance

- We are often unaware of having learned to do these things; we simply find ourselves doing them

- In some cases, we were once aware of the understandings which were subsequently internalised in our feeling for the stuff of action. In other cases, we may never have been aware of them. In both cases, however, we are usually unable to describe the knowing which our actions reveals (Schön, 2016, p. 54)

Schön backs this up it with the idea of common sense being the expression of “know-how,” specifically through action, “a tight-rope walker’s know-how, for example, lies in, and is revealed by, the way he takes his trip across the wire” (Schön, 2016, p. 50). Common sense also proves Schön’s second mode of thinking, “reflection-in-action.” While knowing-in-action is about doing, reflection-in-action is doing and thinking about it (Schön, 2016, p. 54). The example he uses is a study where children were asked to balance blocks which were unevenly weighted. The children knew how the balance point would likely be the visual centre. However, this knowledge failed them when balancing the unevenly weighted blocks. Eventually after trying and testing different balancing points on the blocks, the children understood the balancing point of the blocks was not always the visual centre, but depended of the weight distribution. They then starting weighing the blocks beforehand to feel how the weight is distributed and found the correct balancing point based off this knowledge (Schön, 2016, p. 57). So the children, without being taught, learnt the balancing point depends on weight distribution, and not the visual centre. Schön summarises the results of reflection-in-action as follows:

When someone reflects-in-action, he becomes a research in the practice context. He is not dependent on the categories of established theory and technique, but constructs a new theory of the unique case. (Schön, 2016, p. 68).

This creating a “new theory” for a “unique case” is exactly what simultaneous problem definition and problem solution is. Therefore the term “unique case” can easily be replaced by rhizome, wicked problem, or problem structure, each of which describe unique, ever-changing situations. If we look back at how Rittel and Webber described the process of simultaneous problem definition and problem solution through the example of the poverty problem, you can clearly see how reflection-in-action fits this process. It is a constant loop of testing theories and then returning to the drawing board and then back again – altering the theory and getting a better understanding of the case.

In addition to being a method of simultaneous problem definition and problem solving, reflection-in-action also creates good client relationships. A person who practices reflection-in-action or a reflective practitioner is meant to develop, according to Schön, a very different tone of relationship in comparison to a professional who describes themselves as an “expert” and uses the older linear method of problem solving. The main difference is how a reflective practitioner, although aware they have expert knowledge, also understands this knowledge makes up only part of the problem structure. The rest of the knowledge is found with their clients.1 The term client is used here to mean anyone who comes into contact with the problem and solution. For example within the context of the stairs the cleaner, non-disable user, disable user, builder, materials supplier should all be consider clients. The relationship the reflective practitioner has with their clients is also distinctively more open and honest than, what Schön refers to as, the “Expert”. Where the Reflective Practitioner drops the professional façade in order to create a more free, honest, and open relationship with their clients, including articulating their uncertainties, the Expert prefers to keep their uncertainties hidden, and have a professional distance between them and the clients, while also conveying “a feeling of warmth and sympathy as a “sweetener”” (Schön, 2016, p. 300). The good client relationship the Reflective Practitioner is able to nurture results in a richer exchange of information between the practitioner and the client. In addition the client is also more likely to accept and/or challenge the solutions the practitioner offers (Schön, 2016, p. 302). Both of these results are essential for simultaneous problem definition and problem solution, as you need information to uncover the problem structure, and also have permission to probe the problem structure with possible solutions.

So why are you standing in a hall?

I am standing in an 18th century hall because the issue of the reusing of oral history recordings, especially the reuse of recordings on heritage sites, is a very complex or wicked problem. It is rhizomatic, made up of many peoples subjective view on the issue of handing and reusing oral history recordings, such as the original interviewers, the archivists, the site’s volunteers, and the site’s staff. It is entwined into other issues, for example digital obsolescence, data management, the environmental impact of digital files, and how we value within heritage. It is also constantly moving and changing as I am researching, because it is part of an operating organisation. There are also many parts which are still invisible to me because their access is restricted in some way, again due to me working with an operating organisation. Above all a lot of what I am researching falls under maintenance work, the system which Susan Leigh Star identified as being intrinsically invisible. Because the issue of reusing oral history recordings has all the elements of a complicated problem structure, I cannot solve the problem through the linear method and have to use the techniques of Rittel and Webber discuss and become a Reflective Practitioner practicing reflection-in-action. This action has lead me to standing in the hall, because I started volunteering at the hall and also did a placement at the hall, both of which allowed me to understand numerous things about the problem structure. For example, how staff members can be suddenly assigned carpark duty and have to leave all the work they planned to do that day by the wayside, or the complicated and delicate power dynamics between the volunteers and the staff, or simply how the IT systems work, or do not work. If I was not doing a PhD by Practice it would be unlikely I would have known these things about the problem I am trying to find a solution for. And as so many I have mentioned point out developing a solution when you do not know the problem can be considered unethical.

1 Schön does specify “stakeholders” and “constituents” are used instead of “client” when dealing with multiple groups (Schön, 2016, p. 291). However, I prefer the term client because I feel it communicates the power structure of the relationship better: I am the designer/problem solving serving my clients. I am working for them, they are not working or me.

OHD_WRT_0257 Possible activities and outputs of placement at NCBS

Summary of placement activities and planned outcomes

Original:

During this placement I am looking to do a critical investigation in the past, present, and possible future culture of the archive at NCBS. I will have meetings with current members of staff and others who have previously been part of the archives’ eco system. The main aim of this placement is to look at how an archival habitus is established and how it might be enhanced and supported through the systems and processes of the archive. I will also engage with the day-to-day activities of the archive, which will include experiencing the day-to-day collection of archival materials and public engagement projects.

Levels of Access

If Archives at NCBS is thinking of scaling up and moving material online there are several issues to consider, especially when expanding public access such as, data protection, copyright, the format of the material, to name but a few. And because there are so many factors, different archival material will require different levels of access. I am interested in, how decisions are made about levels of access are and how access is assigned [GS1] to archival materials. Access to oral histories can be especially tricky. I believe tackling this issue will involve identifying the different spaces where people can access material, what the terms and conditions are for each of these spaces, and a matrix which helps categorise where individual archival material can be put.

Institutional memory and the grant cycle

More than 60 students and professionals coming from a variety of career backgrounds and age groups have worked within the walls of Archives at NCBS. This richness of diversity has made the Archives into the innovative and open space it is today. However, this situation does have its drawbacks especially in combination with the grant cycle. A grant often requires things to be achieved within a set time limit, meaning you want to waste as little time as possible. You do not want the new intern spending a lot of time learning all the unexpected quirks of the Archive, exploring ideas that have already been tested, or establishing relationships already established by their predecessors. So how do you avoid losing time? How do you transfer institutional memory from one intern to the next? This is something I would like to explore and attempt to find solutions which help people pick where others left off allowing the Archive to work more efficiently within the grant cycle.

The Archives at NCBS and NUOHUC collaboration project[GS2]

This is probably something to be explored further down the line when certain meetings have been had. From what I have deduced from the few conversations I have had about this project; some thought needs to go into what exactly will be collected. This includes archival material, as there has been mention of getting oral history participants to draw, and legal material as there might be cases where participants are unable to read certain forms. I am happy to contribute my thoughts to this project as I am interested in the relationship between the producers of archival material and the archive.

[GS1]Unsure if this is what you mean…

[GS2]Excellent points

OHD_BLG_0254 Blog post on the first month at NCBS

From a lively archive in Bangalore

Between indulging in delicious food and gandering around the stunning campus of the National Centre of Biological Sciences (NCBS), I sit at a hot desk in the basement where the Archives at NCBS is housed. The term ‘basement’ is slightly misleading as the sun shines through windows which face a sunken outdoor amphitheatre, where I can watch paradise birds flirt with each other in the trees. When not distracted by birds or food, my attention might be drawn away from my work by one of the eleven other people working in the Archive. It is the loudest archive I have ever been in, even when I discount the constant humming of the air conditioning. It is also the most welcoming workplace I have ever worked in. The Archives at NCBS is a hub of multidisciplinary folk, all coming together to build this archive, which is still very much in its infancy, celebrating its fourth birthday on this month. Therefore, a lot of the work is focused on growing the archive, with some team members creating a digital catalogue, others expanding the collection, and many involved in developing the various work flows necessary to keep an archive running.

This development of workflows, which I am also playing a role in, is necessary because, like so many organisations in the GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives and museums) sector, the Archives at NCBS is working within the grant cycle. This automatically leads to a lack of consistency under the staff and therefore creates a somewhat unsettled work environment. From February 2019 to February 2023, around 60 interns have passed through the archives’ doors. When I started my conversations with the head of the archives about doing my placement here, the archives team was three people. Now it has grown to twelve, including two archivists, a software developer, various artists in residence and an outreach team. There are also several other researchers who use the Archives’ reading room and offices to work in. What I am witnessing within the walls of the NCBS basement is how the sudden expansion and change within the archive is causing some growing pains. These growing pains should not be considered a negative, but as part of the natural process of building an organisation. They are what is motivating the development of various workflows.

Developing these workflows is necessary because, while the previous team of three were easily able to know exactly what the others were doing, the current members of the archive team are slightly less sure, even though they are all in the same room. By creating workflows, the workers of the archive, new, old, temporary, and permanent, will be supported in their work, allowing the larger work of the archive to be carried easily through the grant cycles and revolving door of many interns. However, this is not an easy task, especially when everyone still needs to carry out their day-to-day work alongside the workflow development. I am, therefore, doing my bit by creating the archives’ notice and takedown workflow. I am looking into how the archives can edit, redact, and remove archival material and capturing this process in a way which is helpful for users of the archives and present and future archivists.

While overall my first month in India has been delightful; filled with lovely weather, delicious food, and a group of generous and considerate co-workers, I will admit it took me some time to find my feet in the work at the archive. At first it was not clear what I should be doing, but now, with the development of the takedown workflow, I have been given direction, and am glad to be here to help the archive through this unsteady and nebulous time. The Archives at NCBS might not know exactly what it is doing right now, but that is okay; no one really knows what they are going to be at the age of four.

OHD_WHB_0246 Miro board of NCBS placement

OHD_WRT_0171 CDA development update

CDA development update

Here is a brief overview of how the PhD has changed since the project proposal split it into three sections. The first considers the significant changes that have occur globally in the last two years. The second discusses the change in the framing of the situation the PhD is addressing, reusing oral history recordings on heritage sites. And the third looks at the changes in design methodology and theory due to the environment I am designing in and for.

SECTION ONE: HISTORY HAPPENED

Since the writing of project proposal, the world experience significant changes including, the COVID-19 pandemic, further development in the conversation around the Britain’s colonial past, and a constant wave of climate disasters. The Trust did not escape the effects of these changes, having to furlough and make significant cuts to staff during the 2020 lockdown, publishing the report on sites with connections to the British Empire, including Seaton Delaval Hall, and wider actions for the Trust to achieve carbon net neutrality. In addition, the COVID-19 lockdowns also highlighted the public’s need for access to open spaces and nature, while storms, like Storm Arwen, highlighted the threat the climate crisis is to the Trust running open natural spaces. It is because of the changes in the Trust this project has also evolved and the project is unfolding in a very different environment than when it was originally proposed. The project therefore has to think about the environment impact of the designs it is developing and think about how the design might fit in the (post-)COVID structure of the Trust. In the original proposal the project was already thinking about a 360˚ interpretation of the hall but now this seems more important than ever.

It is also interesting to note, while it is true that National Trust sites are to a certain extend run autonomously, they do not operate in a vacuum. National Trust sites function inside the wider structure of the Trust, an extensively complicated network of rules, regulations, and resources. I believe the influence this structure has on the project was slightly underestimated at the time of writing the project proposal. For example, the Trust’s digital infrastructure which has strict rules and regulations about digital storage has become quite the barrier, the extent of which had not really been realised before the start of the project.

SECTION TWO: BUILDING THE FOUNDATIONS

In the summary of the project proposal it is written that “the PhD would generate, in partnership, new knowledge in understanding and addressing visitors’ active engagement in interpreting the past through reusing a National Trust oral history archive.” The big assumption made here was that “a National Trust oral history archive” was either already in existence or would have been easy to set up. What the last two years have revealed is that this part of the task is easier said than done and the struggle in setting up oral history archives that allow reuse is not unique to the National Trust. After I did a deep dive into the many attempts to make oral history recording more reuse friendly through digital tools, it became clear something more fundamental was not being addressed. Most frequently the downfall of these digital solutions was the projects coming to the end of their funding, meaning there was no money to support the maintenance needed to keep the technology running, which eventually resulted in their deterioration.

If we return to part of the original title of the PhD, “sustaining visitor (re)use”, the project initial was about building a system to allow visitor interpretation of oral history recordings. However, two years down the line “sustaining visitor (re)use” seems only achievable if at first, we create a solid foundation on which a system for visitor interpretation can be build and maintained. In order to create these foundations, there needs to be a focus on maintenance and the resources needed to support the storage of oral history recordings, which is something that has been missing from other endeavours into oral history recordings accessible. The resources needed will obviously include labour and money but also energy. As the large carbon footprint of internet servers and the storing of digital files is being realised. This project also needs to think about how we are able to store oral history recordings in the most energy efficient way possible, while still ensuring they are accessible and reusable to a wide range of people. This is especially important with the Trust’s aims for carbon neutrality.

SECTION THREE: CHANGE IN METHODOLOGY

Back in the original proposal Roberto Verganti’s idea of a technological epiphany is mentioned as a possible route for the PhD. However as written in the first section the Trust’s digital infrastructure is slightly rigid and is likely to not accommodate any radical technological innovation, meaning that a technological epiphany is unlikely. What we can still take from Verganti is his ideas around a change in meaning. What does it mean to do oral history on heritage sites? And how does oral history benefit heritage sites in the long term, beyond the idea of volunteer and visitor engagement within a set project timeline? Alongside Verganti’s idea of a change in meaning I have taken on design theory from Cameron Tonkinwise about ‘design for transitions’, which involves thinking about the life of designs outside of the project timeline and Victor Papenek’s six elements of function that lead to a successful design: use, method, need, aesthetic, telesis, association.

With the project design practice there has been another change. Instead of following a step-by-step process of researching, developing a prototype, testing and iteration. I have opted to use ‘infrastructuring’; researching and mapping the existing structure of an institution or system to better understand and communicate where any possible design solutions might fit. And ‘design fiction’ or scenario building as a low-risk method to harvest feedback on possible designs instead of the high-risk method of live testing and iteration. Design fiction/scenario building also seems to be an excellent way to communicate across disciplines.

OHD_WRT_0163 Project Plan

Project Title

Oral History’s Design: A creative collaboration. Sustaining visitor (re)use of oral histories on heritage sites: The National Trust’s Seaton Delaval Hall case study.

Detail of Project Plan (Including key milestones)

First Year

Aims

- To seek how this project will create new knowledge in all fields; heritage, design and oral history

- To integrate into the Seaton Delaval Hall (SDH) community

- To create an awareness of the project both in and outside of the SDH community

- To have a collection of oral history interview recordings by the end of the year

- To gather initial ideas on the design of the archiving system

Actions

- Read and research

- Attend SDH staff meetings

- Talk to the volunteers

- Set up online presence

- Record pilot interviews

- Plan, set up and record interviews

- Conduct initial design workshops

Second year

Aims

- To create a bank of archiving system ideas

- To develop and prototype the ideas into real systems

Actions

- Review the recorded oral history interviews

- Use the recorded interviews in workshops with various parties to generate ideas for an archiving system

- Prototype, test and review workshop outputs

- Iterate as appropriate

Third year

Aims

- To unpack the collaborative process

- To write up findings

Actions

- Review and and reflect on collaborative process

- Writing and editing

Note that throughout the project there will be continuous project updates and feedback opportunities with the community around SDH.

Project impact on well being and mitigating risk

Due to the collaborative nature of this CDA there are many players from different fields that are involved in the various stages of the project. As the research student for this project I am acting as ‘project manager’ for this CDA. This role requires me to take up some organisational work alongside my research. However, I believe that with realistic goals, well delegated time, and clear communication with my supervisors, I will be in a strong position to complete my CDA to its fullest potential. In addition to this, I have also been made aware of the resources that both universities offer to support students’ well being.

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval will be sought when method and sampling strategies are finalised.

Summary of proposed project (500 words)

Oral history’s ‘deep dark secret’ is that its focus on collecting histories has inadvertently led to a neglect of the archives and the option to reuse existing oral histories in historical interpretation. This project draws on new developments in oral history reuse theory and practice, in combination with design, to explore how heritage site visitors can become active curators and historians. In doing so, this project will build an on-site oral history archive, which will continuously collect new content from visitors. The project will consider how, in turn, new data can be generated to shape future collecting. The CDA would propagate new knowledge in understanding and addressing visitors’ active engagement in interpreting the past through reusing a National Trust oral history archive. The archive in question is situated at the National Trust property Seaton Delaval Hall (SDH) which is the case study for this project.

The hall is the ideal location for this case study as it is part of a local community whose history is deeply connected to the hall and vice versa. The volunteers and visitors will play a key role throughout the project. They will not only be the source of the oral histories, but will also help inform the design process for the archiving system. Along with the staff at SDH; the Oral History Unit at Newcastle University; Multidisciplinary Innovation Masters students at Northumbria University; and any other interested parties, the volunteers and visitors will collaborate to create and develop an archiving system that is tailored to their needs as a community. The project aims to document and review this multidisciplinary collaboration, investigating the opportunities and challenges that are uncovered in the process. There will be a focus on what each field can learn from the other and how this might inform future collaborations of the same nature. Simultaneously the project will develop a tool kit for heritage sites who are seeking to work in partnership with volunteers and visitors.

The overall aim of working within the hall’s community is to make a sustainable system. This sustainability will work on multiple levels. Firstly, the system has to be sustainable in order to adapt to and accommodate the new stories that are constantly being added. Secondly, it has to be structured in a way that is straightforward for the National Trust staff to use and manage for many years to come. And lastly, and most importantly, the system should aim to be aware of current and future difficulties that could arise in from the world’s ever-growing and complicated digital-ecosystem. By having the project deeply embedded into the culture of SDH from the start, the archiving system can grow together with the community, hopefully opening the door to the possibility of solving oral history’s ‘deep dark secret’.

Extra documents

OHD_GRP_0162 Project Timetable

OHD_DSN_0158 Research Room Donation Flowchart

OHD_WHB_0157 SDH Placement Whiteboard

OHD_MDM_0028 Answer to questions about project

OHD_BLG_0081 The History of Ideas:

An Introduction to the United Nations Intellectual History Project

by Louis Emmerij

First published in 2005 this article briefly explains the United Nations Intellectual History Project which involved documenting the history of ideas at the UN through archival work and oral history.

The project took a broad approach to ideas looking to “explain the origins of ideas; trace their trajectories within the institutions, scholarship, or discourse; and, in some cases, certainly in ours, evaluate the impact of ideas on policy and action.” I find this great because what they have done is explore the process of ideas instead of just the final idea. In this project they put value on process because as they say “ideas are rarely totally new. They do not come out of the blue.”

Absolutely 10 out of out 10 on the project front however this project, like many, stumbles over the archive. The UN archives sound like a total mess which is not surprising but simultaneously terrifying. And considering they claimed this project to be about “forward-looking history” their outputs were a series of books and 75 oral history testimonies which are meant to be found at www.unhistory.org (which as you might have guessed does not work).

OHD_BLG_0093 Oral History ➡️ Design

My masters in Multidisciplinary Innovation (MDI) taught me how design and its practices can be used in any field in order to create innovative solutions to complex problems. I believe that during this PhD I will use these techniques to help create a solution to the problem of unused oral history archives. This particular flow of knowledge I am completely aware of, however now I would like to discuss the reverse. How can oral history, its practices and its archives influence the world of design?

Let’s start with the reason oral history as a field exists. Oral history interviews are there to capture the history that is not contained within historical documents or objects. These histories often come from those whose voices have been deemed ‘unimportant’ by those more powerful in our society. It could be said that the work oral historians do is an attempt to equalise our history. However, oral histories, unlike more static historical objects and documents, are created in complex networks of politics, cultures, societies, power dynamics and are heavily influenced by time: past, present and future. Some oral histories take on mythological or legendary forms and are not necessarily sources of truth, but they do capture fundamentally human experiences that cannot be distilled into an object.

But how can this help the design world I hear you ask? Well, currently the design world is going through a bit of an ethical crisis. Ventures that started out as positive ways to help the world have brought us housing crises (AirBnB), blocked highways (Uber), crumbling democracy (social media etc.), higher suicide rates (social media), and even genocide (look at Facebook’s influence in Myanmar.) It’s all a big oopsie and demands A LOT of reflection. Why did this go wrong? How did this go wrong? What happened? Have we seen this before? How can we stop this from happening again?

We did a lot of reflection during MDI, but we also didn’t do enough. One, at the time we never shared any of our own reflections with the group and two, we now cannot revisit any of these reflections or the outcomes of our real life projects because they weren’t archived. The only documents I can access is my own reflective essays and a handful of files related to the projects, most of which solely document the final outcomes. This results in me only being able to see my own point of view and no process. Post it notes in the bin, hard drives no longer shared and more silence than when we were working in the same room. So what do we do if one of our old clients came to us asking how we got to the final report? Or after having implemented one of our designs are now experiencing a problem which they feel we should solve? Did we foresee it ? What are we going to do about it? I don’t know ask the others. It’s not my problem.

Now imagine this but on a global scale in a trillion dollar industry with millions of people (a relatively small proportion of the world) and very little regulation. And I am not just talking about Silicone Valley for once, but every global institution in the world. My supervisor told me that the World Trade Organisation once came to him asking for his help in setting up an oral history archive. The reason they needed this oral history archive was because they had all these trade agreements but everyone that had worked on them had retired and taken their work with them. They had the final outcome but not the process. Zero documentation of how they got there. Post it notes in the bin. They eventually did complete the oral history project but then did not have the documents to back these oral histories up because post it notes GO IN THE BIN. Whoops.

So, how did we get here?

In order to answer this question you need to be able to look back and see a fuller picture than your own point of view. We do this by not doing what the World Trade Organisation and MDI 2018/19 did. We create a collateral archive made of our post-it notes, digital files, emails etc. and we talk. We then put the collateral archive and the recordings of us talking together in one place. The reason we cannot rely solely on the collateral archive is because, as I said previously the documents cannot encompass the human experience to the extend that oral histories can. Also, not everything is written down some things will be exclusively agreed on verbally so the oral interview should (hopefully) fill in some of the blanks.

Once all this documentation has come together it needs to be made accessible to EVERYONE (with probably some exceptions.) This has two outcomes, firstly, it answers the question how we got here. People can analyse and reflect on the process in complete transparency. When something goes wrong we can look back and work out why. And secondly, in the case of design we now have a fantastic bank of ideas, a back catalogue of loose ends and unpursued trails of thought. Setting such a bank is already being examined in the field of design. Kees Dorst collaborated with the Law department at his university (I think) because he wanted to see how the Law department was able to access previous cases to help the present cases.

“Design […] seems to have no systematic way of dealing with memory at all” – Dorst, Frame Creation and Design in the Expanded Field p.24

In conclusion, people are increasingly aware that they need to capture their process in a constructive and archivable manner. Which is something I highly encourage for ethical reasons but also because archives are cool and you can find cool stuff in them. I am going to integrate this trail of thought into my PhD by being active in the creation of my collateral archive and also suggesting oral history interviews to be taken from all those involved.

(There is another reason why I would like to take oral history interviews of those involved, which hopefully is made clear in the ethics section of the site)

I hope that by integrating oral history into the design process it will push design into a more ethical space.