Newcastle University Press Release, 30th October 2019

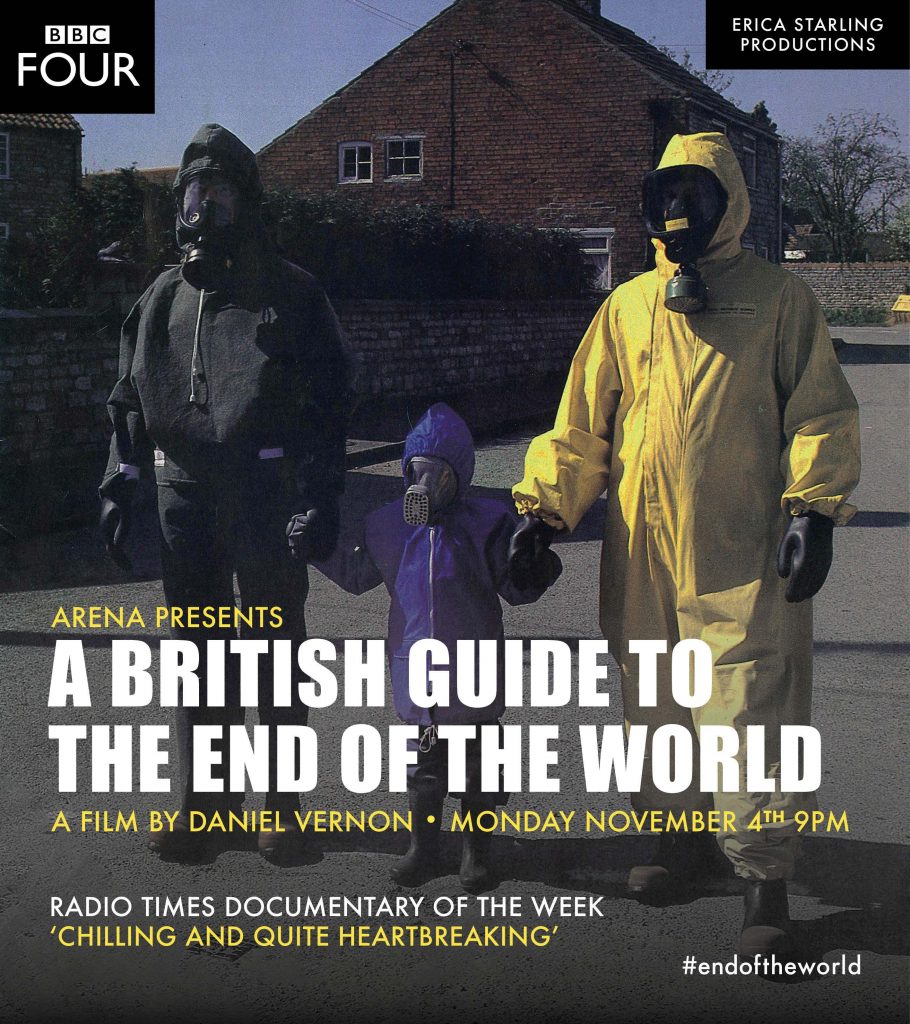

Research carried out as part of a PhD has led to a new BBC Four documentary examining Britain’s response to the Cold War.

A British Guide to the End of the World came about after a TV producer heard Newcastle University researcher Michael Mulvihill speaking about his thesis, which looks at how creative arts can investigate the effects of the nuclear deterrent on society.

Michael was at a series of workshops organised by the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Northern Bridge Doctoral Training Partnership when he was asked to pitch his thesis to a group of television producers.

Now, he is an associate producer on the 80 minute film which is directed by BAFTA winner Dan Vernon and produced by award winning production company Erica Starling Productions. It is being broadcast as part of a Cold War season on BBC Four, timed to coincide with 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

“It is really amazing to see over four years of research come to life in this film,” says Michael, an interdisciplinary researcher from the University’s School of Arts and Cultures and School of Geography, Politics and Sociology. “Objects that had been just archive items have been given voices. It’s quite an amazing experience.”

Operation Grapple

The Arena film begins with Operation Grapple – a series of British thermonuclear bomb tests that took place in the south Pacific islands between 1957 and 1958. It offers unique access to footage, some of it which was previously classified, from ex-military personnel who filmed their arrival on Christmas Island to carry out these tests.

It then shows how over succeeding decades the British authorities tried to plan for the prospect of nuclear war reaching these shores – a devastating event that never happened. Long neglected broadcasts from news and government sources reveal a time when paranoia was stockpiled, leaving a generation traumatised.

“I think the film dramatically shows how the authorities struggled to conceive a system civil defence against a weapon of incredible power,” says Michael. “Weapons that still pose a threat today.”

The Unblinking Eye

The Cold War period has preoccupied him for years. As a child in the 1980s, he would time how fast he could run home from primary school in case the four minute warning, telling of impending nuclear attack, ever sounded. It took him six minutes.

Decades on, his fears of war between the East and West have informed his PhD in Fine Art and Geography. And as well as the documentary, his academic research led to him becoming the first ever artist-in-residence at RAF Fylingdales in North Yorkshire – the UK early warning system where the four minute warning would be signalled. The residency led to a large scale museum exhibition.

“The Cold War was something that felt very real when I was growing up,“ he says. “Thirty years on, a lot of people have forgotten what that period felt like, that underlying fear that the world may be on the brink of nuclear war at any time.”

The exhibition at Whitby Museum, The Unblinking Eye: 55 Years of Space Operations on Fylingdales Moor, makes public for the first time previously unseen objects from the station alongside new artworks by Mulvihill. It also presents new research on the history of RAF Fylingdales in local, national and international contexts, highlighting the North York Moors’ integral role in international space monitoring and the cultural legacy of the iconic ‘golf balls’.

Rachel Woodward, Professor of Human Geography who supervised Michael’s PhD thesis says: “Michael’s work as an artist and a geographer shows how seemingly unorthodox approaches to studying military and security issues can really help us all understand their history and their present effects so much better.”

A British Guide to the End of the World will be broadcast at 9pm on Monday 4 November on BBC4.

The Unblinking Eye: 55 Years of Space Operations on Fylingdales Moor is on show at Whitby Museum until 17 November.

A screening of A British Guide to the End of the World and a conversation with Michael Mulvihill, director Dan Vernon and award winning documentary filmmaker Alison Millar, will take place at Newcastle University later this year.