Angela Plessas is a third year PhD student in Sociology at Newcastle, studying polycystic ovary syndrome as a diagnostic category. Like many students, she has had to adapt her research project in light of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, shifting from interviews to a document-based approach. This transition has been challenging, but ultimately rewarding.

Documentary research methods are generally considered the realm of the Historian, not the Sociologist. Although they don’t necessarily have a ‘bad name’ in social research, they are certainly misunderstood. The precise steps for carrying out documentary research are seen as vague, and the resulting analysis prone to bias. Documentary research is usually considered, at best, complimentary to a researcher’s main choice of methods, but never the main method itself.

I was once guilty of these misconceptions myself, until COVID-19 changed everything. When the country went into lockdown in March, I was about to start interviewing GPs who have cared for women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). I knew these interviews would be challenging, but I felt ready. I had ethical approval, my interview schedules had been tried and tested, and I was in the early stages of recruitment. A few days into lockdown though, when communication with potential GP participants completely dried up, it became obvious that things had changed.

What is PCOS?

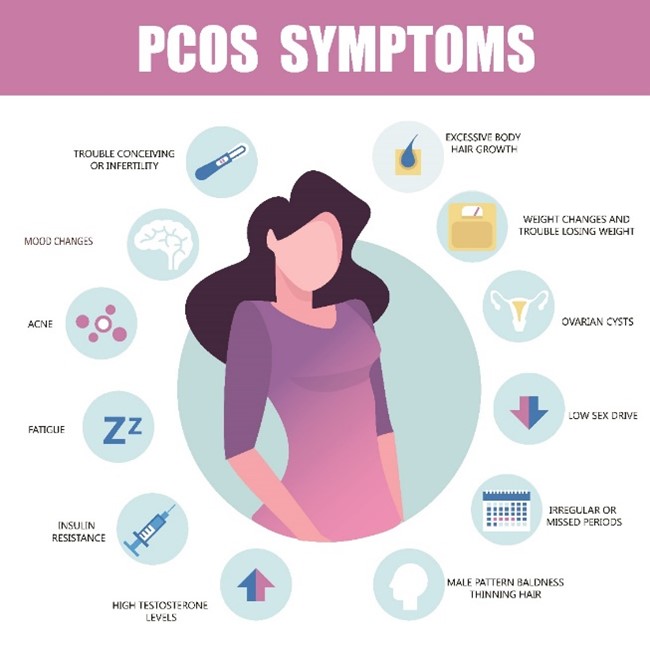

PCOS is a common endocrine condition, thought to affect 1 in 10 women around the world. My original ambition for this study was to ‘shed light on the true lived experiences of women with PCOS’, with a focus on experiences of diagnosis. However, thanks to my supervisors and their experience in in-depth research with medical documents, I began to realise that there was much more to PCOS diagnosis than that which takes place in a GP surgery. Many of these trends and practices are rooted in medical literature – its ambiguities, controversies and debates.

How my research changed

During lockdown, many GPs were working remotely and had to prioritise the most essential tasks over others. Even now, routine care remains severely disrupted, and GPs are tackling a huge backlog of care for those who had treatment postponed during lockdown. Recruiting and interviewing GPs in this environment seemed near impossible. Like most PhD students at a similar stage to myself, I needed to consider alternative options.

For my study, documentary-based research methods offered a practical way forward and an opportunity to conduct an entirely original study of PCOS-literature. Since adopting these methods, I have realised how rich and ripe for analysis PCOS medical literature is. PCOS has had numerous names throughout its history. It was once named after the researchers who ‘discovered’ it – Stein and Leventhal – before being known as polycystic ovary disease, and more recently, polycystic ovary syndrome. Although this name refers to ‘multiple cysts’ and to ‘ovaries’, many women with PCOS have no ovarian cysts whatsoever. Equally, many women who do have ovarian cysts, do not have PCOS. The fact that a huge and expansive body of PCOS medical literature exists, and that significant diagnostic dilemmas remain, also indicates a host of unanswered questions which need exploring.

These include questions like:

- What happened to Stein and Leventhal?

- Why does the name of the condition revolve around ‘cysts’ and ‘ovaries’?

- How many PCOS symptoms ARE there?

- How many PCOS ‘phenotypes’ ARE there?

- What makes it a syndrome?

There are a number of advantages to using documentary research. From a practical perspective, this approach is extremely COVID-safe. A documentary-based study also allows for a detailed and focused examination of the stories and debates which exist in relevant literature. These stories often go untold and unexamined and could help provide answers for the dilemmas and difficulties experienced by professionals in the field, as well as by women living with PCOS.

Doing documentary research should not be considered an ‘easy’ option. It must be systematic and rigorous. Narrowing down large samples of documents involves meticulous sorting and searching. The work is entirely desk based and I spend a LOT of time staring at documents on my screen. I occasionally experience ‘medical language overload’ where, as someone with no medical background, I start to feel overwhelmed by the new and unfamiliar terminology. Below is a good illustration of what this looks like!

My advice for others thinking of changing their projects is to talk to your peers and supervisors as much as possible. Many of us across Sociology and the HASS faculty have now been through significant project changes, some of which have been much more dramatic than this one! Try to stay positive and know that your project can still be truly engaging and enjoyable, even if it’s not what you originally had in mind.

I quickly learned to love and enjoy my newly adapted project. Although I’d still like to interview PCOS professionals, I am finding that using only documentary research methods is a truly effective way to understand the nuances and complexities of the PCOS diagnostic category. If it had not been for having to change my project due to the global pandemic, I would never have discovered this.

This is so interesting Angela. As someone who spent many happy (???) hours in my first postdoc research job parsing out the meaning and value of how government policy documents construct the problem of ‘women in science’ I always endorse a document based project. The irony of PCOS applying to women with no ovarian cysts is a truly excellent and truly social research puzzle.

Thank you Lisa, really hoping to gain some understanding as to why PCOS has been named as it has, as well as following some of the more recent debates about the potential renaming of the condition.

Such a great read! It’s interesting and relieving to hear how your plan B wasn’t necessarily seen as second to your original methods and actually allowed you to think about things in a new way!

Thanks Melissa! Yes really enjoying the Plan B and grateful that my project wasn’t too severely disrupted. Hope your fascinating Covid-adapted project is still going well!

This is interesting. I’d be interested to know how you approached the documentary research methodologically – in other words, how did you characterise the method and what authorities did you cite?

Thank you Ann. The specific approach I’m using is the framework analysis method- my analysis (of around 150 articles) is based on a systematic process of familiarisation and immersion with the data, aiming to develop themes which are firmly rooted in the data and taking a primarily inductive approach. I’m avoiding using any analysis software for fear that this could obscure vital contextual information.

I’ve drawn a lot on the work of my supervisor Geth Rees and his colleague Tim Rapley, who advocate a detailed and rigorous approach to documentary analysis. I’m also drawing on some very recent studies of diagnostic categories in medical literature, particularly one by Erik Rasmussen which looks at the presentation of MUS (medically unexplained symptoms) in medical documents.

The aim is to understand the social construction of diagnostic categories in medical literature and why the PCOS category has developed along a particular trajectory and been the subject of so much contention and debate.

I hope I have answered your question and thank you for reading my blog post!

Thank you – that reply is very helpful. And thanks for the blog too.

Ann