By Cassie Bakshani

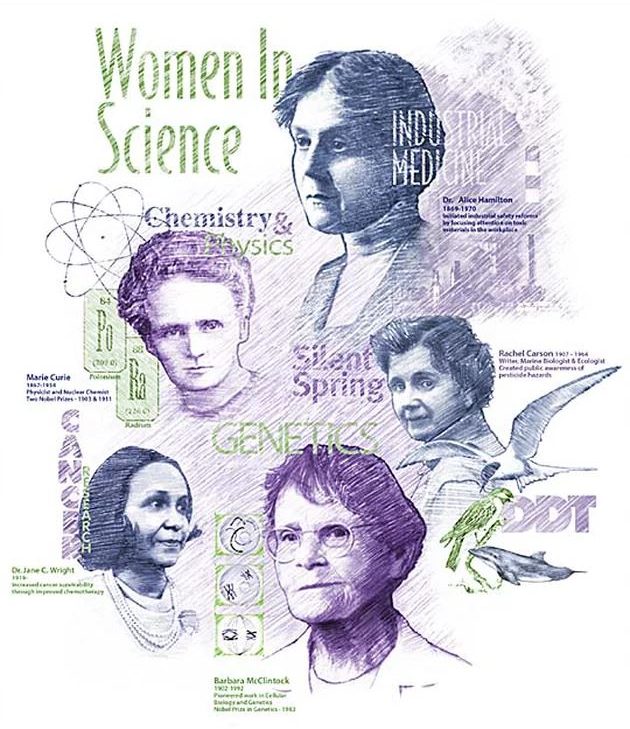

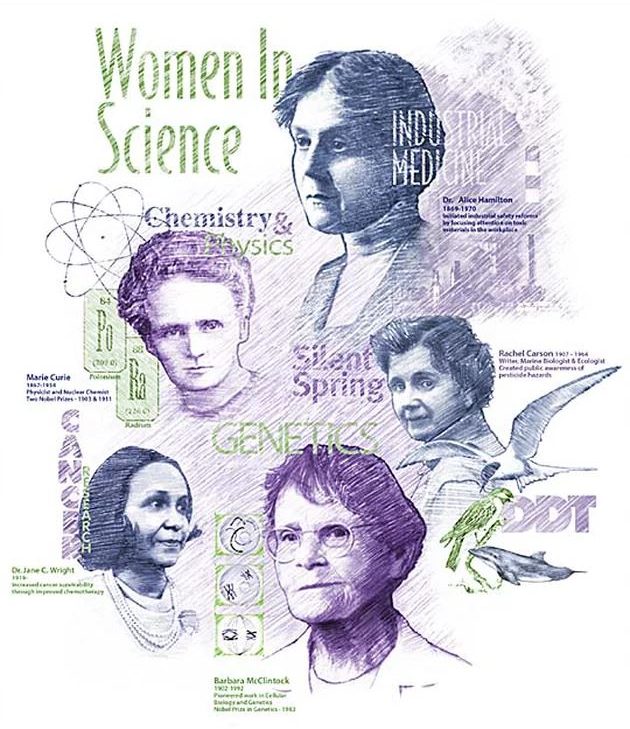

Last week we celebrated the 150th anniversary of the birth of Marie Curie, the first person in history to become a double Nobel Laureate. Remembered for her discovery of polonium and radium and her contribution to development of cancer treatments. It was deflating to read in the same week that only 47% of respondents, from a 3000-person survey conducted by YouGov, could name any woman scientist. In light of this, I thought I would share some of the incredible women- some you will (hopefully) know and others you may not- who have amplified my interest in STEM fields and reinforce my aspiration to pursue a career in science.

Rosalind Franklin: British Chemist

After attaining a PhD in chemistry from Cambridge University in 1945, Franklin was appointed at the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l’Etat in Paris. Here she worked with Jacques Mering, who taught her crystallography and X-ray diffraction. Franklin developed an expertise in X-ray diffraction and in 1951 began applying these techniques to the study of DNA fibres. This ultimately led to her discovery of the structure of DNA, documented in the famous Photograph 51. Unfortunately, however, Franklin was never truly accredited for this monumental discovery.

Grace Hopper: Mathematician, Military leader and Computer Programmer

Hopper was responsible for the compiler, which is a precursor to the universal Common Business Orientated Language (COBOL) and translates worded instructions into code, so that they can be read by the computer. Hopper was instrumental in revolutionising computer programming and thus the development of modern computing.

Shirley Ann Jackson: Theoretical Physicist

Jackson’s 1950s research led to the development of caller ID and call waiting. This technology laid the foundation for solar cells, fibre optic cables and portable fax machines. Interestingly, she is also the first African American woman to achieve a PhD in theoretical solid state physics from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. An outstanding achievement, made even more impressive when you consider that of all physics PhDs given in the USA, only 19% of these are awarded to women, and of that, only ~2.5% go to women of minority groups.

Peggy Annette Whitson: Astronaut and Biochemist

Whitson achieved numerous firsts for women astronauts, being the first woman commander to lead a space exploration and the first woman to command the International Space Station- not once, but twice. Not only this, but Whitson also surpassed her predecessor Jeff Williams’ record for most days spent in space by a NASA astronaut, creating a new record of 665 days.

Mary Anderson: Businesswoman and Inventor

It’s likely that you have used Anderson’s invention countless times without realising. In 1903, Anderson was awarded a patent for the development of a windscreen wiper, which would alleviate the dangerous and highly impractical need for a driver to lean out of the cabin to clear the windscreen. Anderson showcased her invention to numerous car companies, but it remained unpopular due to the perception that it would ‘distract drivers’. The windscreen wiper later became standard in car design and manufacturing; however, Mary was never recognised as the inventor and thus never profited.

Rosalyn Yalow: Nuclear Physicist

Yalow developed radioimmunoassay together with Dr Solomon Berson, which can be used to measure small concentrations of bioactive molecules in the blood, including hormones. Using this method, Yalow and Berson tracked insulin, by injecting radioactive iodine into their patient’s blood. In doing so, they found that type 2 diabetes can be attributed to an inefficient use of insulin by the body, rather than a lack of insulin.

Esther Lederberg: Microbiologist and Geneticist

Lederberg was true trailblazer in bacterial genetics, responsible for the discovery of the lambda phage. The lambda phage is a bacterial virus with a mechanism of virulence which differs from other viruses; it doesn’t destroy cells, but rather integrates its DNA into the bacterial DNA, thus ensuring it is spread to subsequent generations. It is still used successfully as a tool to study genetic recombination and gene regulation. In addition, Lederberg invented the replica plating technique, which can be used to isolate and analyse bacterial mutants and monitor antibiotic resistance.

Josephine Cochrane: Socialite turned Inventor

Cochrane was known for hosting many dinner parties at her home with husband William Cochran. Due to frustration with inadequate cleaning of her fine china by their housekeeping staff, she endeavoured to create a machine that could clean her dishes more effectively. Whilst at this time she was successful in producing a prototype, the machine was never put into construction. Following the death of her husband in 1883, Cochrane was left with $1,535.59 and crippling debt. This instigated the commercialisation of her invention and following collaboration with mechanic George Butters, to optimise construction, Cochrane was awarded a patent for her Garis-Cochran Dish-Washing Machine in 1886.

Amy Cuddy: Social Psychologist and Harvard Business School Professor

Along with Susan Fiske and Peter Glick, Cuddy developed the Social Content Model and The Behaviours from Intergroup Assect and Stereotypes Map, which are used to make judgements of individuals within social situations in two-trait dimensions, warmth and competence. This is now a universal framework which can be applied across different cultures, historical and modern-day cases to predict stereotyping and intergroup prejudices. Cuddy also delivered the second-most viewed TED talk of all time, with over 32 million views.

May-Britt Moser: Professor of Neuroscience and Founding Director of Centre for Neural Computation

Moser’s work, along with husband Edvard Moser, focusses on the neural basis of spatial location, including the discovery of grid cells in the entorhinal cortex. Her research group is working to elucidate the functional organisation of the grid-cell circuit and how this contributes to memory formation within the hippocampus. She shares a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Edvard Moser and John O’Keefe, which was awarded in 2014.

Ellie Cosgrave: Lecturer in Urban Innovation at UCL

Cosgrave is a civil engineer by training and works now as a lecturer in urban innovation within STEaPP City Leadership Laboratory, where she is also Deputy Director. This initiative focusses on inclusive engineering, with three different target areas: gender, the smart city and how the creative arts can influence design processes. One aspect of Cosgrave’s research addresses how urban design can be improved to tackle sexual violence in cities. Cosgrave is also a Director at ScienceGrrl, a grassroots organisation which showcases the work of women scientists from diverse backgrounds.

Masayo Takahashi: Ophthalmologist and Project Leader in Laboratory for Retinal Regeneration at RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology

Until recently it was assumed that the adult mammalian retina was incapable of regeneration, however research conducted within Takahashi’s group has shown that new retinal neurons can be generated following damage. Using these insights, Takahashi developed a new approach to produce retinal pigment epithelial cells by reprogramming mature cells back into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS cells). In March of this year, Takahashi’s iPS cell protocol was deployed in the world’s first successful retinal cell transplantation to treat macular degeneration.

Tamara Rogers: Reader in Computational Astrophysics

Newcastle University’s very own Dr Rogers specialises in numerical simulation of hydrodynamics and magnetohydrodynamics of giant exoplanets, also known as ‘hot Jupiters’. Dr Rogers used an unusual observation, that atmospheric winds on planet HAT-P-7b are variable and can move uncharacteristically from eastward to westward, to estimate the strength of the planet’s magnetic field. This ground-breaking research was published in Nature Astronomy and provides a new foundation to explore the formation and evolution of our solar system, as it can be used to elucidate size, formation and migratory paths of far-off planets.

Within the UK, the contribution of women to the total STEM workforce stands at just 21%. However, these examples highlight, that despite women representing a minority within STEM careers, we are continually at the forefront of innovation and discovery. So, just imagine what could be achieved with fair representation of the sexes in STEM.