Photo credit: Christina Julius

By Jess Leighton

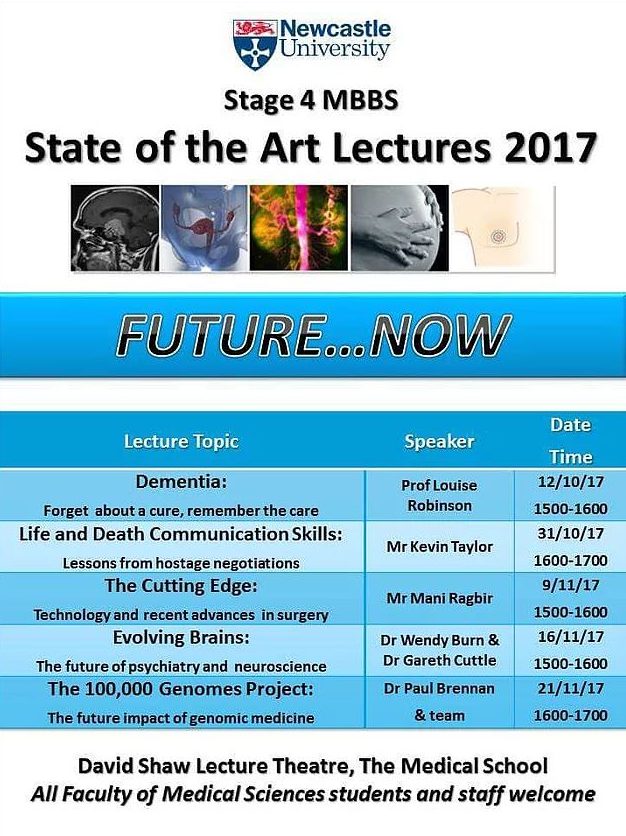

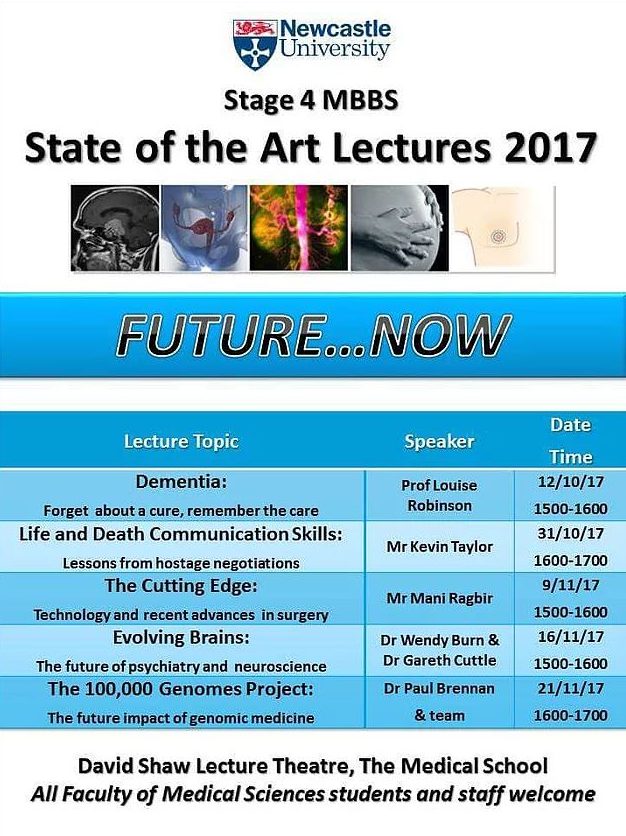

Everyone knows communication is important, but receiving training from an Ex-Chief Inspector and FBI Hostage Negotiation Program graduate may seem a little excessive for medical students. However, Kevin Taylor has used his experience – from suicide intervention to managing the 2011 Manchester riots – to establish a career in teaching excellence in communication; definitely vital in medicine.

The second talk in the Newcastle University State of the Art Lecture Series is titled ‘Life and Death Communication Skills: Lessons from hostage negotiations’, and is not as niche as it sounds. Meaningful interactions are not only the basis of good healthcare, but are also key in good research. A huge amount of studies into public health use these skills, and the Institute of Health & Society’s work on good health across the population is a great example.

The IHS works with patients in their research, some of which is directly around effective communication to improve patient care (more information here). As medical research at Newcastle focuses so much on patient impact, involving them in research may become more prevalent, and call for a different set of skills in scientific research – communication.

Mr Taylor will tear open what we think we know about communication – from that key first impression, through the unspoken rules of conversation and down to what you need to know about yourself to be an exceptional communicator. Having applied his vast knowledge around the world, the talk is sure to have something for everyone.

Kevin Taylor will be speaking on Tuesday 31st October from 4-5pm in the David Shaw Lecture Theatre.

By Leonie Schittenhelm

Forgotten your password yet again? Jamming the keys harder and harder with every try even though you have tried this one three times already? Only to finally (your keyboard breathes a sigh of relief) give in and request a new password. If you have been there, don’t worry – it might just be how tired you were last Thursday.

Researchers at the School of Computing Science at Newcastle University are interested in finding out how a user’s personality traits and other factors influence how they choose passwords as well as the likelihood of successfully remembering them. To do this they asked 100 non-computer science students to create a password, which they had to recall to access a login one week later. The catch? Half of the students had to complete a cognitively exhausting task immediately before thinking up a password. The results were clear: the more mentally exhausted a participant was at time of password creation, the less likely they were to remember it the following week.

But the study, cheekily called ‘Why Johnny Cannot Remember His Password – An Empirical Investigation’, didn’t stop there. They also tested participants for common personally traits, and assessed password strength as well as if this particular password had been used by the student in another context before. Interestingly people who scored high in terms of agreeableness – a personal trait associated with kindness towards other people and compliance with rules – were the most likely to choose a completely new password. This could suggest that the nagging e-mails about cyber security do work, but possibly only on the people already receptive to these kinds of messages. Male participants were four times more likely to choose a completely new password, but this came at the cost of remembering it the following week, which was only at about 50%. Another surprise? There does not actually seem to be very much difference between the difficulty to remember a weak or a strong password.

So when you choose your next password, remember to do it when well-rested and don’t be afraid to choose something quite long. I personally might keep a little note of it in a safe place – at least until the following week…

By Emma Kampouraki

Research has been constantly criticised in recent years. It seems rather odd that while increasing efforts have been made to upgrade the regulatory framework as well as the level of research, we are facing more than ever research outputs and publications of low quality or even results of trials that still remain unpublished. However, there are some simple steps that could improve the published research outputs.

1. Reducing publication bias

First and foremost, research results, positive or negative, should be published without reservation. I often hear early-career scientists complaining about being constantly rejected by journals for their negative results that lack significance. Rarely will I find a well-known researcher publishing studies that failed to prove the hypothesis. Whole books have indeed been written about the publication bias.

Equally, protocols that failed because of not easily predictable parameters should also be reported so that similar attempts are avoided. One reason for this is failure to critically assess the prior literature and another is the unspecified statistical assumptions in the analysis of studies. A statistician should be consulted to calculate sample sizes that are required for the target power of study and to set the relevant assumptions from the beginning.

Negative results and unsuccessful protocols should be seen as equally important and we should always allow them to influence our decisions to conduct further research based on previous failed attempts, the same way as positive results urge further study.

2. Maintaining transparency in research publishing

Peer-review is powerful precisely because it is made by peers; scientists that know how to recognise high-quality research and well documented research results. Most journals today publish work that has been peer-reviewed by at least two reviewers. Selecting a journal in which low quality studies with obvious pitfalls have been published is all but good practice.

Moreover, transparency is well maintained when study protocols and data analysis plans are published well in advance. These should be in accordance with the published results when the study is completed and any reasons for deviation from the initial plan should be well justified. Most researchers should be happy to make the complete set of data publicly available, for the purposes of not only transparency but also meta-analyses. Study funders should grant access to detailed clinical data in response to legitimate requests from both researchers and regulators. These data-sharing initiatives are increasing more and more lately and should be supported.

3. Clinical trial results

Randomised clinical trials are a special category, as they are considered the gold standard in biomedical research. In reality, not all questions are answered with a clinical trial that includes an intervention. Observational studies are very powerful especially when they are well designed and bias is reduced. It is required by law that all trial protocols are pre-published at clinicaltrials.gov. Other details such as recruitment goals, data analysis plan and sources of funding are recorded as well. Funders and researchers should stick to their commitment to publish the (positive or negative) results within a timeframe after completion to inform next steps that might already be in progress (e.g. research funding applications for similar study).

4. Systematic reviews

Last but not least, systematic reviews are an incredibly powerful tool to assess the quality of existing evidence and identify gaps in current knowledge. Every large trial should be supported by a systematic review that justify its planning and of course its cost. Otherwise, there is a great risk that the particular study may not add much to the problem and therefore it won’t be cost-effective. Systematic reviews should be reproducible, peer-reviewed and according to the Cochrane standards.

Each and every new generation of researchers should feel the responsibility to maintain the quality of research that the scientific community demands. It is now more essential than ever that we provide powerful and undoubtable evidence simply because we rely a lot on it to make informed decisions in clinical practice and patient management. We are all involved so we should care!

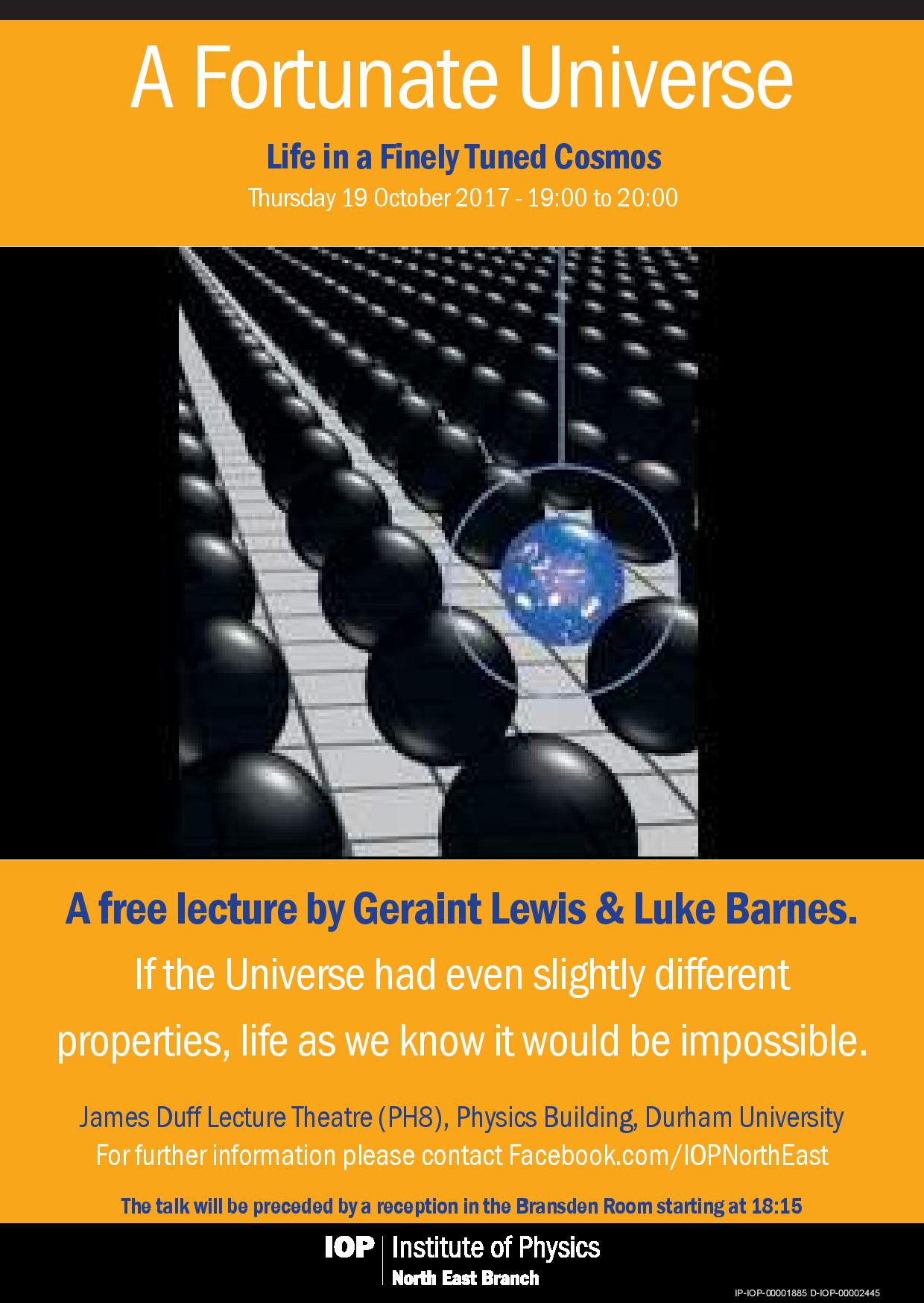

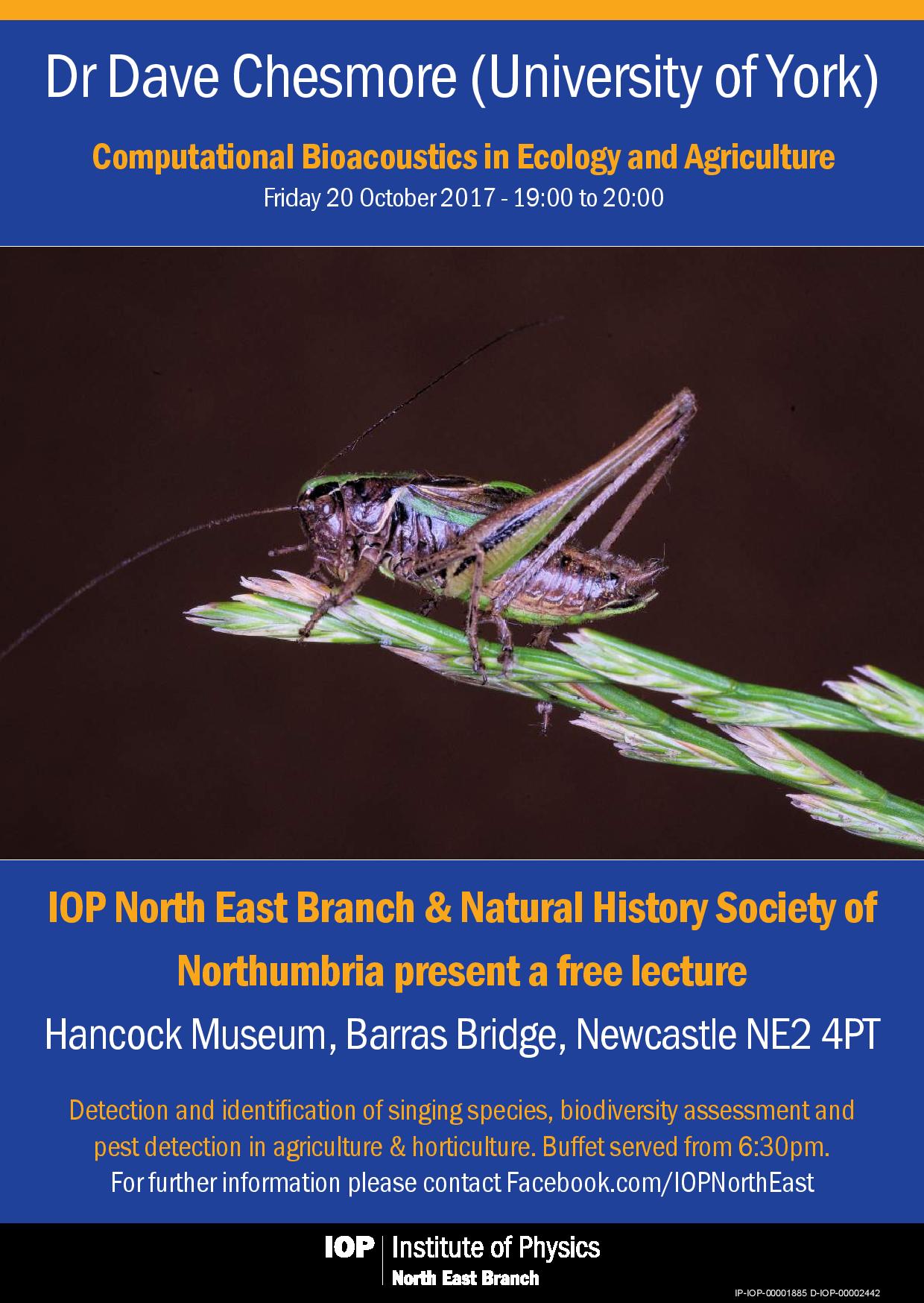

This week the Institute of Physics North East Branch is putting on two free public events!

A Fortunate Universe – Life in a finely tuned cosmos Thursday, 19 October 2017, 19:00 – 20:00, James Duff Lecture Theatre (PH8), Physics Building, Durham University

Application of Computational Bioacoustics in Ecology and Agriculture Friday, 20 October 2017, 19:00 – 20:00, Hancock Museum, Barras Bridge, Newcastle upon Tyne NE2 4PT

Full details can be found here.

By Justin Byrne

In my PhD, I compare ancient British woodlands with younger ones in an effort to describe how microbial biodiversity, and the associated ecological processes, change over time. Scientific endeavours like this focus on building generalisations, but what is the use of a generalisation if, in the real world, things are always atypical?

Biodiversity, the breadth of variation in the living components of an environment, tends to increase over time. Below is a picture of some tanks of standing water in our office, initially these tanks were used to age water for our aquarium. When spring began, the water would quickly fill with algae so we stopped using it. Instead of throwing it away, we left it, occasionally topping it up with wastewater from aquarium water changes. When we put a few plants in there things really kicked off and now the tanks teem with life. Water boatmen, snails, water fleas and no doubt plenty of other microscopic inhabitants have colonised the tank. Nature is the same but slower.

In natural systems we generally expect environments to go through a series of successional stages. First, colonisers arrive, generally fast growing, with high dispersal and plenty of offspring. At a time it was popular to refer to these species as r-selected species (r for high growth rate). These reshape their environments with their activity, waste, and their death, providing altered environments for other species to colonise. As more species arrive, they continue to change their environment until long living species generally crowd out and dominate, forming a climax community. These, were once popularly referred to as k-selected species (k for Kapazitätsgrenze, the German word for carrying capacity – the stable population limit of the environment). This is succession, a conceptual model of how ecosystems behave. British woodlands are the basis of my work and have an extensive history of management, not unlike my water tanks. The Ancient British woodlands used in my research have not yet reached a climax community, the theorised final state of succession. They do not conform to the model. Perhaps the post-glacial wildwood reached climax over the thousands of years of succession it experienced before humans reshaped the British Isles. Perhaps chaotic processes within it prevented it reaching that point. Despite having good generalisations about how the environment should shape itself, in reality things are more messy.

We base our models of how ecosystems work on imperfect individuals. I attempt to look past the individuality of woods with a carefully designed study with lots of replicates. Generally, I might find that the diversity of microbes in woodlands increases over time. Alternatively, “middle aged” woodlands might be most diverse. Statistics gives me an idea of how trustworthy this generalisation is. However, it remains impossible to say what a certain wood will be like in a few decades or centuries. Whatever relationships I find, individual woods may entirely buck the trend. The strength of scientific theories is in their ability to predict general trends. Their weakness will always be in predicting individual events.

Any understanding of the mechanisms behind observed results is going to be a generalisation, and for that we sacrifice certainty. I think that is why many have come to doubt the advice of experts; those who can tell you what should happen, but never what will happen. Developing scientists have to become comfortable with uncertainty, while striving to increase the confidence of their assertions. Offering assurance is not a natural part of this skill set, which can be troublesome when a scientist is called upon to explain an item of news or a development (see the ongoing climate debate). There are two clear responses to this; either science, being uncertain, is a poor arbiter of truth, or certainty is a western virtue that should be valued less highly. To see the downsides of each worldview, one need not look far.

By Jess Leighton

The Newcastle University State of the Art Lectures kick off this week with Professor Louise Robinson, director of the Institute for Ageing. Starting this showcase of Newcastle’s real-life research impact with a medical field constantly expanding with new challenges seems only fitting.

“Live Better for Longer” is the Institute for Ageing’s ethos, and this is no small challenge. Mental and physical health are two obvious emphases for the team, but they are also working on the broader well-being of older people, including community independence and use of technology. As medicine advances and we live longer, there are many challenges which the Newcastle University Institute for Ageing aims to address; allowing these extra years to be spent independently and in the best health possible.

Ageing research is nothing new for Newcastle – the biggest and most developed ageing cohort study in the world was started here in 2006. The Newcastle 85+ study followed up 1,000 older people and was ground-breaking in the field of ageing, exploring issues from sleep to genetics and diet to eyesight.

Professor Louise Robinson – who has led the unit to attract over £35million in research funding – comes from a Primary Care background, and champions community-based dementia care in particular. While the team explore issues from diagnosis to treatment, there is also a focus on high quality care for those who already have dementia. This research is very sensitive in involving a vulnerable group of patients – but absolutely key to high quality care as well as treatment.

Professor Robinson is speaking on Thursday 12th October from 3-4pm in the David Shaw Lecture Theatre, Newcastle Medical School, and all are welcome to hear more about the current research. More details about the Institute of Ageing’s work is available here.

By Leonie Schittenhelm

Hello and welcome back to another instalment of ‘Wacky scientific papers with Leonie’! With the winners of the Ig Nobel Prize for Improbable Research 2017 announced just over two weeks ago, it is not surprising that the internet is abuzz with the surprising, mind-blowing and just plain old weird contestants honoured this year. Each year these prestigious prizes are given to research that – in their own words – first makes people laugh and then makes them think. Here we collect some of this year’s winners and mix in some old favourites for good measure. Let us know your favourite funny paper in the comments!

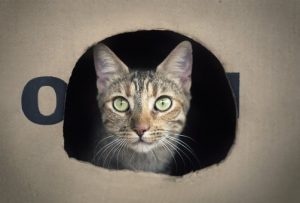

1. ‘On the rheology of cats’ or can a cat be both a solid and a liquid?

Rheology is a field that is primarily concerned with the flow of matter, both in liquid and solid state. The author of this paper, M.A. Fardin, charmingly argues that cats can behave in different ways depending on the surface they are lying on and the space they are trying to manoeuvre themselves into. His methodology? ‘1. Bring an empty box. 2. Wait.’

Rheology is a field that is primarily concerned with the flow of matter, both in liquid and solid state. The author of this paper, M.A. Fardin, charmingly argues that cats can behave in different ways depending on the surface they are lying on and the space they are trying to manoeuvre themselves into. His methodology? ‘1. Bring an empty box. 2. Wait.’

2. ‘Equations of the End: Teaching Mathematical Modeling Using the Zombie Apocalypse’

Modelling how quickly and widely infectious diseases can be transmitted is a complex mathematical undertaking but immensely valuable for disease management. But how can you teach these complex mathematical skills to students without scaring them off? Simple answer: Zombies!

Modelling how quickly and widely infectious diseases can be transmitted is a complex mathematical undertaking but immensely valuable for disease management. But how can you teach these complex mathematical skills to students without scaring them off? Simple answer: Zombies!

3. ‘Pigeons can discriminate “good” and “bad” paintings by children’

A classic in the world of scientific questions no one has even thought of asking before. This study first asked adults to label children’s paintings as either ‘bad/ugly’ or ‘good/beautiful’ and then tried to teach the distinction to pigeons – with surprising successes! Pigeons can apparently learn what is considered beautiful to human eyes and use both colour and pattern of the paintings to come to their assessment.

A classic in the world of scientific questions no one has even thought of asking before. This study first asked adults to label children’s paintings as either ‘bad/ugly’ or ‘good/beautiful’ and then tried to teach the distinction to pigeons – with surprising successes! Pigeons can apparently learn what is considered beautiful to human eyes and use both colour and pattern of the paintings to come to their assessment.

4. ‘Shit happens (to be useful)! Use of Elephant Dung as Habitat by Amphibians’

While clearly important research, the title of this paper is more than cheeky! Even more admirable however is the type of experiments undertaken to yield this data: Ahimsa Campos-Arceiz examined no less than 290 (!) elephant dung piles to see if any amphibians had made their home in them. That’s research dedication right there.

5. ‘What happens if we don’t defend academic freedom’

More serious in tone, this paper was published to protest the increased legal pressures on international universities in general, and the Central European University in particular, that are pushed by an increasingly volatile Hungarian government. The paper itself is short, because what happens if we don’t defend academic freedom? ‘No abstract 1. No introduction 2. No argument and contribution 3. No analysis 4. No conclusion and avenues for future research 5. No more questions asked’.

By Cassie Bakshani

It’s easy to get bogged down and overwhelmed by life’s responsibilities and forget to take time to look after yourself; my previously fractious mental state and perpetual anxiety were a testament to this. I prioritised work intensely and neglected my interests, at the expense of my health and mental wellbeing. I took me a long time to realise that this lifestyle was entirely unsustainable and even then I wasn’t sure how to rectify it.

My first tentative step was scheduling time for myself, with the aim of reinvigorating old interests and acquiring new ones. That’s how I stumbled upon yoga. It looked like a fun class to do at the gym I’d just joined and two of my friends were keen to try it too. What I hadn’t anticipated was that beginning practising yoga would be a metaphorical (and actually, incidentally rather literal) sigh of relief for both my body and mind. A few sessions in and I was generally a bit less tense, ten sessions in and I was looking upon the week ahead with greater clarity and perspective. Nearly one year, one inversions class, 6427 handstand attempts and innumerable falling-on-face incidents later, I’m a different person mentally. I now do two taught sessions and three-four hours of independent practise weekly and I think it has opened me up to many of the restorative benefits yoga has to offer; it allows me to reflect, refocus, be consistently more productive and less irritable. I know some of you reading this may be a little concerned by the lack of solid evidence to back up those last statements, so let me provide some for you now.

It is well-known that meditative practices such as yoga facilitate the transition in the body from the sympathetic nervous system to the parasympathetic nervous system, i.e. from fight or flight mode to rest and digest mode. This is because focusing on and controlling breathing allows practitioners to achieve a state of deep relaxation and mental calm. Subsequently, the body reduces cortisol and catecholamine levels, including epinephrine/adrenaline and norepinephrine/noradrenaline, which trigger anxiety responses, such as increased heart rate and blood pressure. Moreover, a study published this year found that, when sustained for a period of 3 months or more, yoga stimulated production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). This protein supports growth, survival and plasticity of hippocampal and cortical neurons and is concurrently involved in mood regulation and promotion of stress resilience, therefore could play a significant role in cognitive restructuring in response to stress.

Convinced yet? Maybe not, but I definitely encourage you to at least give yoga a try. It may not necessarily change your life, but it could make your day, and your head, that little bit lighter.

Namaste.

Here are some great yoga events and classes/workshops taking place in the North East in the coming months:

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/yogamatters-north-east-yoga-mala-tickets-36821561281?aff=es2

http://happyyoganewcastle.com/beginners-yoga/

http://www.yogalilies.co.uk/workshops/?options%5Bids%5D=489&options%5Bsite_id%5D=44972

http://www.yogalilies.co.uk/workshops/?options%5Bids%5D=496&options%5Bsite_id%5D=44972

By Leonie Schittenhelm

The amount of common diseases we have yet to cure can seem overwhelming sometimes: no week without a looming ‘Alzheimer’s epidemic’ headline or an advert on the bus warning about the 1 in 3 chances of having a stroke. Surely all energy and research funds should be channeled into treating and healing these wide-spread diseases? Yes and no. While learning more about these diseases is incredibly important to help the people affected by them, researching less common diseases should not be forgotten.

A disease is considered rare if less than 5 people in 10,000 are affected by it. While relatively few other people will share the same disease, the amount of rare diseases ranges between 6,000 and 8,000. This means that over 30 million people in the European Union alone are estimated to suffer from these rare conditions, often without relevant therapeutic options and frequently misdiagnosed for years. To make matters worse, significant research results are difficult to obtain due to inherently small sample sizes and experts in a specific rare disease being equally scarce.

However, with the advances of genetic diagnostics, diagnosing rare diseases correctly and research to find better treatments is finally in reach. And while the problem of small local sample sizes persists, the European Union has pledged to fund collaborative projects tackling this problem as part of the Horizon 2020 programme. One such example is the RD-Connect network that is being built by Professor Hanns Lochmüller and his team at Newcastle University. The online platform collects a range of clinical and genomic data on rare diseases, while encouraging the researchers to use their resources to upload their own, building a huge database on rare diseases.

Understanding these diseases better does not only help the people affected by them, it can also increase our understanding of biochemical pathways in the general population. Because the majority of rare diseases are caused by a single gene mutation, symptoms can be usually traced back to the malfunction of a specific gene. This means that elucidating why a set of symptoms occurs can not only provide therapeutic options for patients, but also reveal the function of a specific gene in the healthy population.