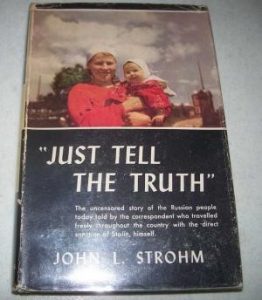

In May 1947 John Strohm published an account of a visit he made to the Soviet Union in 1946. The book Just Tell the Truth: the Uncensored Story of How the Common People Live Behind the Russian Iron Curtain was intended to be an honest account of everyday life in Stalin’s Soviet Union in the aftermath of the war. Strohm hoped to give his readers a glimpse behind in the Iron Curtain as the cold war began, humanising ordinary Soviet citizens. In 1946 he resigned his job as the managing editor of the Prairie Farmer in order to travel to the Soviet Union and write about its people. Apparently his access to the Union was only granted after a personal appeal to Stalin. Precisely how free Strohm’s access to the Soviet Union was isn’t entirely clear, he claimed to have permission to go where he wanted, to talk with whom he liked, and to take photographs at will, provided he “Just Tell the Truth.” Given how visiting westerners and visiting journalists were usually managed, normally monitored by official handlers, this seems a little unlikely. Yet the book offers a genuine insight into how ordinary Soviet citizens lived, worked and possibly thought. The Rotarian, for example, certainly thought that it was a sympathetic study of ordinary Soviet people. Strohm published some accounts of his travels as he went in various newspapers and magazines, collating them with other impressions in this volume.

Strohm took his own photographs on this trip; unlike John Steinbeck’s A Russian Journal published in the same year, which could call on Robert Capa’s talents. Remarkably I’ve managed to purchase what appears to be an original, which was distributed by ACME. The seller had bought a large collection of photographs from press collections that had been dissolved, perhaps when ACME was sold to Corbis, or Corbis changed ownership in 2016.

The image captures a recently demobilised Red Army veteran clutching a pair of boots, which the image description on the back explains as: “Just demobilized, this Red Army soldier of Byeorussia carries a pair of U.S. Army shoes – UNRAA supplies. The shoes bring $100 per pair in Moscow. The solider turned down a barefoot women’s offer to barter a supply of canned goods for the shoes.”

Although this naturalistic image serves Strohm’s purpose of humanising Soviet citizens, it raises a number of interesting questions. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) operated in Belorussia and Ukraine, but not in Russia. For more on UNRRA in the Soviet Union see Andrew Harder’s article: “The Politics of Impartiality: The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration in the Soviet Union, 1946-7.” Journal of Contemporary History 47, no. 2 (April 2012): 347-69. Link

However, there are a number of curious aspects of this image and the description. Demobilised veterans according to the 23 June 1945 demobilization law were to be supplied with a pair of footwear on their discharge. It seems odd that UNRRA was directly supply shoes to a veteran who already appears to be wearing a serviceable pair of boots (sapogi), especially when people nearby why barefoot. UNRRA supplies, however, were perhaps being issued to demobilized veterans by the Soviet authorities. Footwear was a deficit commodity in the immediate post-war period, and returning soldiers were perhaps privileged citizens in getting access to these supplies. Although, it should be noted that obtaining shoelaces of the requisite length was not necessarily going to be easy (unless those are laces tied around the veteran’s right wrist?). The description on the back of the photograph, however, demonstrates just how widespread barter and private trade was in the immediate post-war period.

Strohm’s trip to visit to the Soviet Union certainly deserves further consideration, both in his own account but perhaps also in his papers preserved at the University of Illinois Archives: Link Given Strohm’s extensive international connections throughout his career, an intellectual biography and international contacts and networks would be a really interesting project.

N.B. 18/10/19

Just to add that this photograph was actually published in Strohm’s book.