30 March is marked as National Pencil Day in the United States, which has led me to do some thinking about whether pencils really should be thought of in national terms. As I hope to demonstrate in this blog the pencil has a rich international history, which crossed international borders as easily as a hastily written letter scribbled in pencil.

So why is National Pencil Day marked on 30 March? I thought that this might have to do with the Derwent Pencil Musuem which claims Keswick in the Lake District as the home of the world’s first pencil. However, National Pencil Day is an American creation, marked on 30 March the day when the inventor Hymen Lipman registered the first patent for a pencil with an eraser integrated into the end of the pencil in 1858.

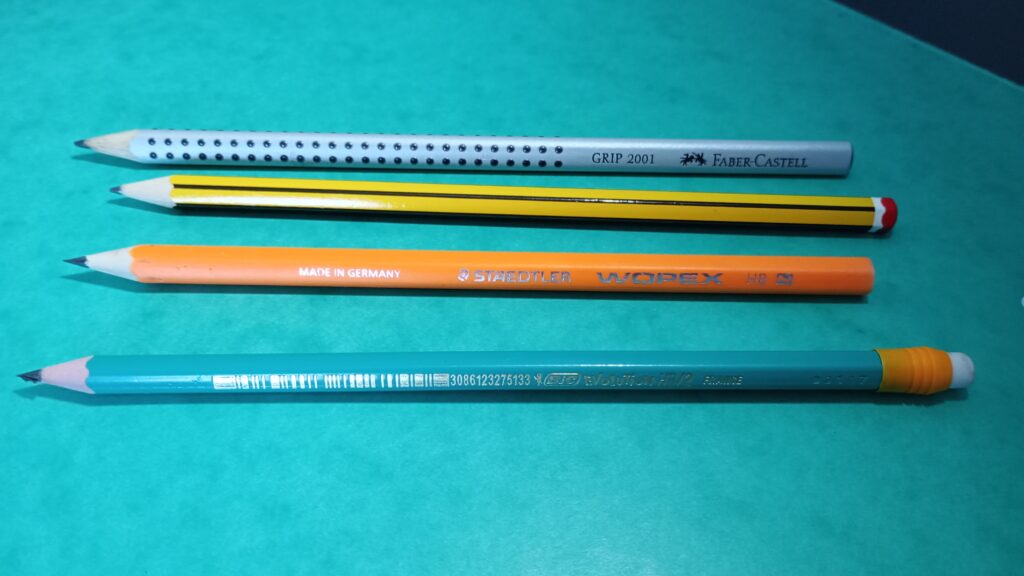

However, should we see the pencil in national terms? Lipman himself was born to English parents apprently in Kingston Jamica. When I look at the pencils I have at home they come from brands across Europe. Although I love writing with a fountain pen, I still love writing in pencil, especially a well sharpened quality pencil. You can see a selection of my favourites below. I especially enjoy the Faber Castell Grip 2001 pencils, which are a German brand, and the Staedtler Wopex pencils, again another German brand. But, of course there are host of international pencil brands. Pencils might not be something that you associate with Russia, but for me there are lots of international connections with Russia and the pencil. One of the things that always stuck in my memory from Robert Service’s biography of Lenin was that Lenin loved a tidy desk, complete silence as he worked, and precisely sharpened pencils to write with (pp.99-100). I have visions of Lenin working with these highly sharpened pencils in the British Musuem in London, or at his desk in Zurich. However, this is just the beginning of a series of international connections that spring to mind between pencils and Russia.

The Russian word for pencil – karandash (Kарандаш) has apparently existed since the at least the seventeenth century, but the word apparently has a turkic origin. A quick internet search tells me it borrows from the Turkish karataş (“black slate”), from kara (meaning – black) and taş (meaning – stone). This is interesting, because when I started learning Russian I had originally assumed the word karandash might owe something to the Swiss brand Caran d’Ache. But, it turns out the direction of travel was the opposite. In 1924 the Swiss company Fabrique Genevoise de Crayons, was renamed Caran d’Ache. Here, the history begins to get really interesting. The pencil manufacturers borrowed the name Caran d’Arche not directly from the Russian word for pencil, but from pseudonym of the Russian-French satirist and political cartonnst Emmmual Poiré. Incidentily, Poiré was born in Russia 1858, the same year that Hymen Lipman was patenting his pencil, but later emigrated to France. Poiré’s family were in Russia apparently because his grandfather a member of Napoleon’s invading Grande Armée had been wounded at the Battle of Borodino, and stayed on in Russia. Or course, this wasn’t the only famous individual with the pseudonym Karandash there was also the famous Soviet clown, the stage name of Mikhail Nikolayevich Rumyantsev.

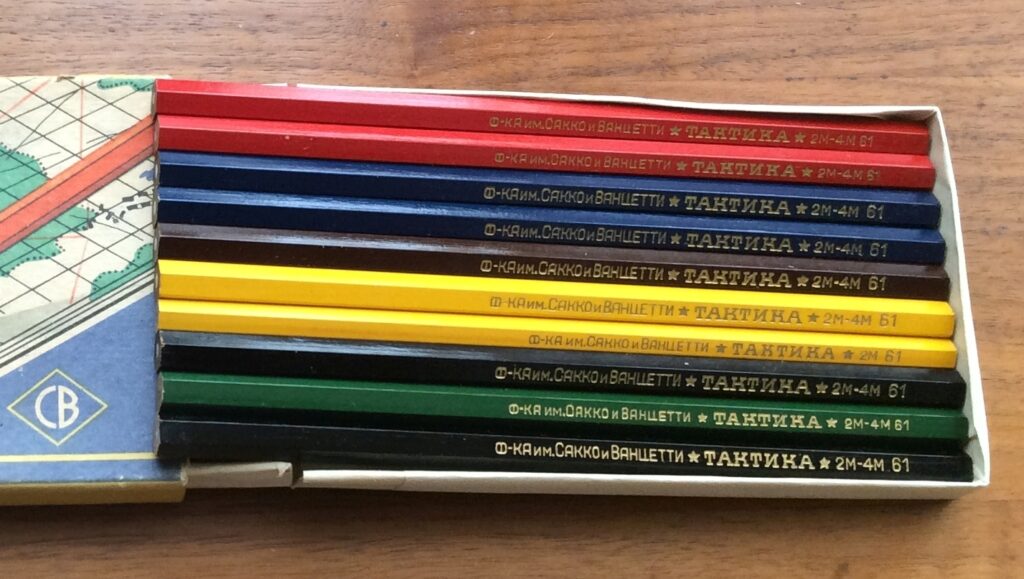

Finally, one of the most famous brands of pencil in the Soviet Union was the Sacco & Vanzetti brand, the favoured pencils of none other than Joseph Stalin. The pencil factory was named after the murdered anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, both Italian anarchist immigrant to the United States of America, who were murdered on 23 August 1927. The Sacco & Vanzetti factory had originally been founded by the American Industrialist Armand Hammer in around 1926, in a phase when the Soviet project was still enamoured with American industrial modernism, but around 1930 he was bought out by the Soviet state, who renamed the factory after the murdered anarchists. The name of the new factory helped preserve an international dimension, with a echo of both America and its Italian communities. Incidentally, the famous Soviet writer Vasily Grossman, had worked at the Sacco & Vanzetti pencil factory for approximately two years in the mid-1930s.

So, my point is really that even before one starts to think about where the materials for pencils come from, particuarly the cedar wood preferred in production, pencils turn out to be remarkably international.