This book, published in 1584, intends to prove that those that claim to be witches may be false.

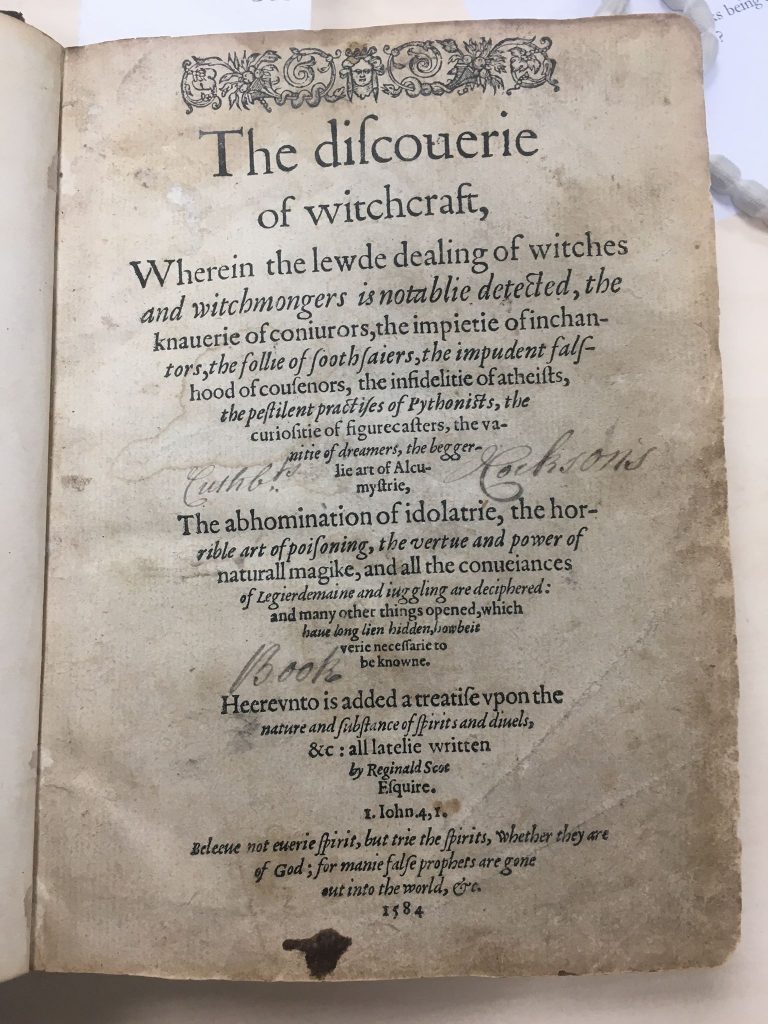

The Title Page

The purpose of this page appears to be an effort to prove that Reginald Scott’s goal is not opposite to God’s, but is aligned with Christianity. Scott refers to a verse as evidence that God is against those that pray on the superstitious, which warns to ‘try the spirits, whether they are of God; for many false prophets are gone out into the world.’ Furthermore, Scott even groups atheists together with ‘soothsayers’ (fortune tellers) and ‘conjurers’, depicting these as, like atheists, not of God.

The Reader

An interesting element of the title page is the owner’s writing; it appears as though the owner did not only mark the book with his name, Rockson, but also was interested in the book’s font, and tried to practice writing in this style. Printing was a relatively new technology at the time, and books being mass printed with beautiful fonts, not by hand, while being expensive were also more accessible and therefore seeing this must have been interesting to the reader.

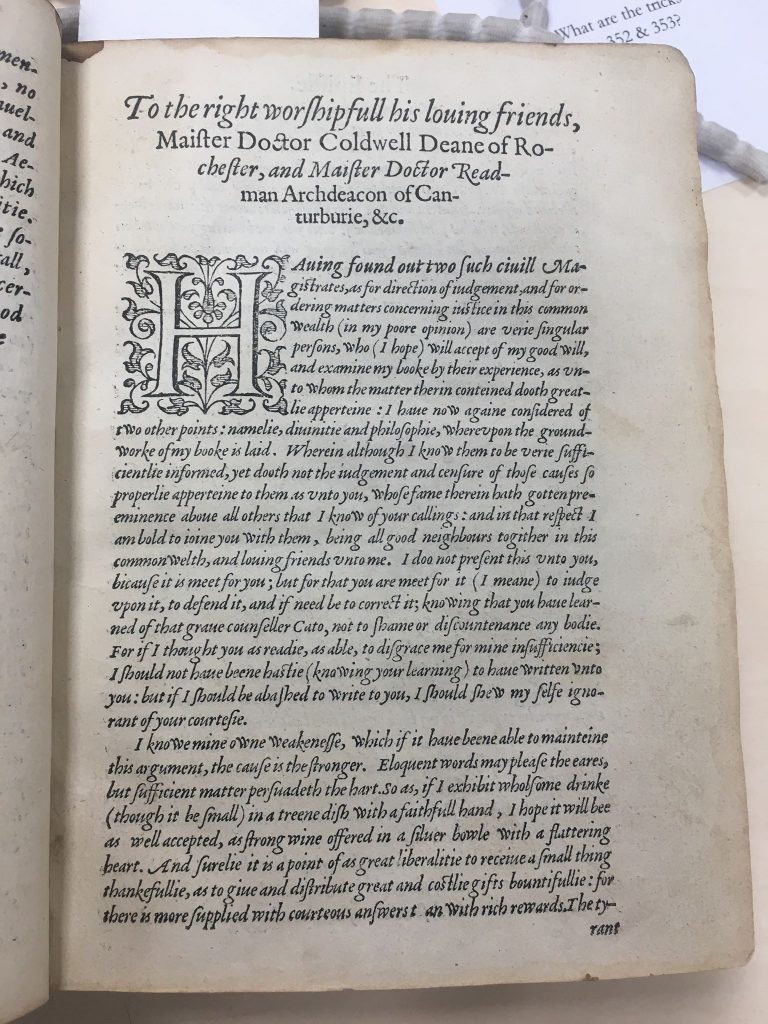

Dedications

Reginald Scott dedicated his book to three figures (four including the reader, which reveal some interesting things about the authorial intention.

Manwood, Sir Roger (1524/5–1592), judge

Reginald first dedicates this book to Sir Roger, praising his judgement. This could be because Reginald, again, seeks to justify himself, and prove that he is not against judges which may condemn witches, merely wanting to aid their efforts. This grovelling could be because he is afraid that the publishing of this book may cause him to be in trouble with the law, especially if he insults such an esteemed member of the government.

Scott, Sir Thomas (1534×6–1594), landowner

Reginald Scott spends a generous amount of time exalting his cousin, Sir Thomas Scott. While it seemed as though this is because this cousin was an influence of some sort, research has revealed that Reginald’s fervent worship of his cousin was probably due to the author’s financial reliance on this very cousin, a man which inherited from their grandfather ‘thirty manors.’

Coldwell, John (c. 1535–1596), bishop of Salisbury

Reginald dedicates his book also to a man named John Coldwell with great admiration, stating that he is interested in continuing the bishop’s work. While Coldwell had not publish anything witchcraft related, at least nothing surviving, the character’s background, which involves both achieving a master’s in Cambridge as well as becoming a man of the church, is much like Scott’s stated goal. While Reginald believes in logic rather than blind belief, at his core he is a man of God, wanting to separate religion from superstition.

Dedication to The Reader

This dedication is interesting because it assumes that the reader is already prejudiced about superstition, therefore it seems to be to a person engrossed in popular culture. This passage simply asks the reader to be open minded, because if they are a participating in groupthink and following their emotions, their bias will deny the contents of the book. Therefore, Reginald is seeking to use logos rather than pathos to convince the reader.

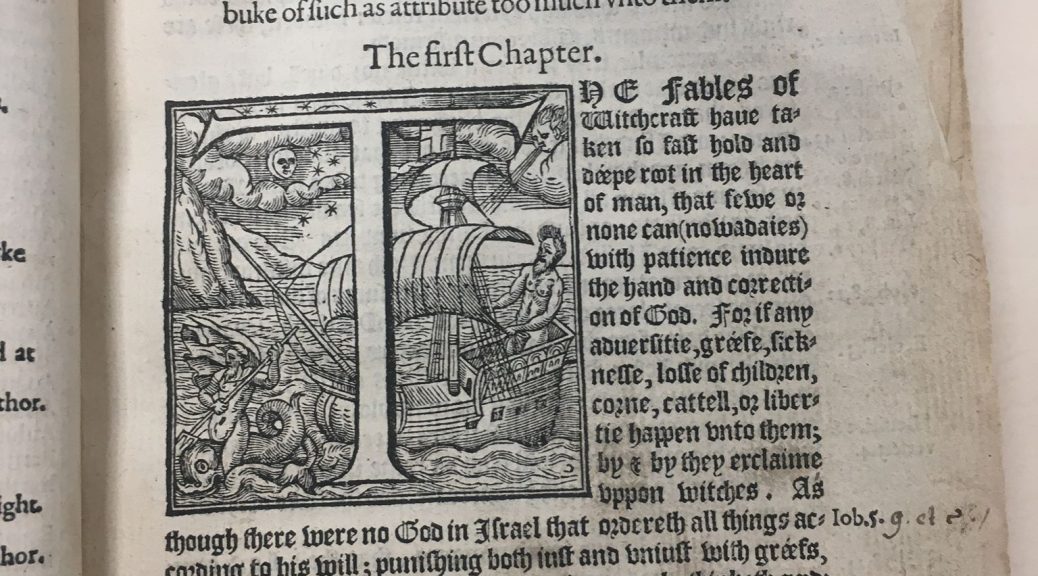

The Diagram

This illustration is especially interesting as it is a look into how illusion was used in the theater. Reginald portrays how a decapitation may be created in a performance, and uses this as evidence to show that those that claim they are magical can use these same techniques to depict a false illusion.

List of Authors

This appears to be an early form of citation. The reason for this could be not only to give credit, but a way of using ethos. As the list of references is so large, this proves that Scott was involved in a lot of research, therefore is very knowledgeable on the subject, which may sway the reader into agreeing with Reginald’s stance on superstition.

Corrections

There is a list of amended sentences in this book, which is likely due to the infancy of publishing at the time. Because books were mass printed, which was expensive, it would be difficult to correct individual pages. Therefore, perhaps it was cheaper to later print a page with the corrected sentences, with references to those pages.

Citations

Pictures taken by Victoria Mezzetto

Jack, Sybil M. “Manwood, Sir Roger (1524/5–1592), judge.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. January 03, 2008. Oxford University Press. Date of access 30 Oct. 2019, <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-18014>

Knafla, Louis A. “Scott, Sir Thomas (1534×6–1594), landowner.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. January 03, 2008. Oxford University Press. Date of access 30 Oct. 2019, <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-24914>

PlantinMoretusmuseum. “DVD – Museum Plantin-Moretus (English).” YouTube, YouTube, 5 Nov. 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=FCTK5FVXaC4.

Rundle, Penelope. “Coldwell, John (c. 1535–1596), bishop of Salisbury.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. May 21, 2009. Oxford University Press. Date of access 30 Oct. 2019, <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-5844>

Wootton, David. “Scott [Scot], Reginald (d. 1599), writer on witchcraft.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. September 23, 2004. Oxford University Press. Date of access 30 Oct. 2019, <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-24905>

This was great, well done Omer (& Victoria M who was also working on this)! I like the way that you demonstrate not only what the different paratexts are, but how you might interpret them: e.g. that Scot is trying to demonstrate that he’s not an atheist right from the beginning, even though it is a sceptical book. Some nice use of the ODNB here to help you draw the network of dedicatees for this book, and their relationship to Scot. The woodcut illustrated letters at the start of the dedication to Manwood and to the readers are amazing too! They look like they’re representing mythological narratives, which maybe once made sense in the context of another book, but have been reused here, and de-contextualised. And yes, right about the index/list of authors: notice that they are ‘forren’ authors, and going down the list we can see a lot of known classical and Renaissance ‘humanist’ authors from continental Europe, who as you point out demonstrate that Scot has produced a lot of research. The correction are known by their Latin name (because it was originally an Italian humanist practice, imported to other countries) ‘errata’. It also demonstrates that Scot (and other humanist writers) are imagining an ‘active’ reader, who is made part of the process of interpretation by being encouraged to correct their copies themselves.