The production of early printed books is almost unrecognisable from the printing process of today. Printing was an artisan skill as there was not the large scale production methods that are commonplace in the modern industry. Books were printed sheet by sheet, rather than page by page and then these sheets were folded to form the book. The less times a sheet was folded, the more expensive the book was. Folios, where the sheet was folded in half, were therefore the most expensive and quartos – a sheet folded four times – were cheaper. Books were printed on the Gutenberg Press with movable type, which was designed by Gutenberg (surprisingly enough) in the 15th Century but brought to England by William Caxton.

The printing of books was paid for by publishers. Printers, who manufactured the physical book and stationers, who bind the pages and sell them to customers, were all instructed by the publishers, who would pay an author roughly £2 for a manuscript. All of these professions had to belong to the Stationer’s Company, which the publisher paid a licensing fee for each text. The publisher also had to provide the printer with the paper and pay for a first run of 200 copies – an expensive business! They then sold unbound copies directly to customers and stationers. Because they paid for this whole process, publishers determined the content of title pages, e.g. the advertising feature of the book. They sometimes wrote dedications and commissioned dedicatory verses for their author.

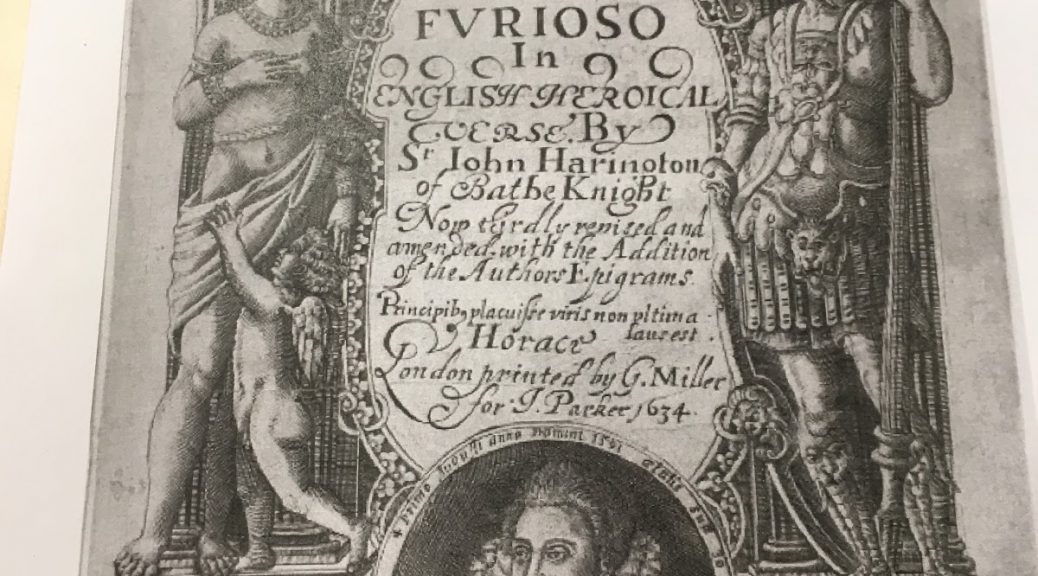

From the front cover we are provided with basic information about the book. We learn that the text is John Harrington’s translation of Ariostos Orlando Furioso, which was published in 1634. We also get an insight into that form, as it states that it is written in English, heroical verse. The cover states that it is “Printed in London by G. Miller for J Parker,” so we can understand that the printer was G. Miller and J. Parker was the publisher. It also states that it is “Thirdly Revised,” so we know that it is the third edition. Upon further research, we found that the editions were published in 1591, 1607, 1634. All three editions were dedicated to Queen Elizabeth the first, because she was his patron.

The intricate illustrations show that there are clear classical and divine themes to Orlando’s Furioso, with the inclusion of Gods, cherubs and angels around the two figures. The way the two figures are positioned and the inclusion of what appears to be Cupid suggests the romance element to the narrative. There is a large illustration of Ariosto, showing that this is his original work and that this text is Harington’s English translation. The quite dominating illustration of John Harrington presents his want for authorship.

Further research on Early English Books Online proved that the title page was engraved, as were illustrations, with copper rather than wood – this would result in better quality, more intricate, more impressive illustrations with perspective and shading, which in turn would make it a more expensive text to buy. There also proved to be 142 copies of all 3 copies in existence, suggested it was a popular text as there still remains multiple copies across numerous countries’ and cities’ archives.

It would also seems that the only other surviving text Harington wrote was the ‘Metamorphosis of Ajax’, and paratexts of that such as ‘Apologie for Ajax’.

Phoebe, Holly, Pearl, Charlotte

A nice introduction to the printing context outlied in the week 4 lecture, leading into your focus on Harington’s copy of Orlando Furioso. Remember to mention copy specific issues (e.g. the copy we saw doesn’t have the title page: why do you think it went missing? Was there any other evidence in that copy that there had been damage?). Nice discussion about the classical themes of the text: love, yes, but also war. On the pillars below them, you can also see that there are scenes of romance and war in the pillar. The title also tells us that this revised text has ‘addition of epigrams’: what do you think those are? Doesn’t their inclusion also demonstrate that there are additional texts written by Harington other than Ajax, as you suggest? Elizabeth I- as well as his patron- is also his cousin!