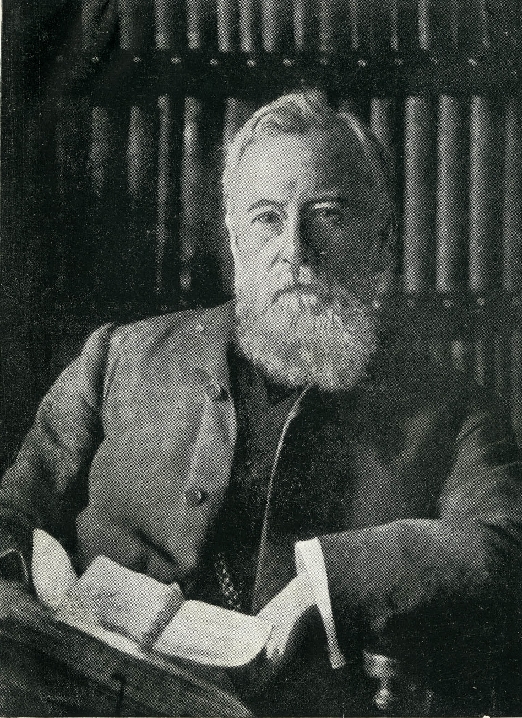

2nd March 2011, marks the centenary of the death of Robert Spence Watson (1837-1911). This image of Spence Watson is pasted into the front of a copy of one of his publications, The Reform of the Land Laws (1905), contained in the Spence Watson/Weiss Archive (SW 10/9).

Robert Spence Watson was born in Bensham on the outskirts of Gateshead. His family’s house there, Bensham Grove, remained his home for all of his life. Born into a Quaker family and a lifelong Quaker himself, Spence Watson was aware from an early age of the presence of injustice in the world and the efforts made by those who strove to redress the balance. His father, a solicitor, was a campaigner for the first Reform Bill, an advocate for Catholic Emancipation, and northern secretary of the Anti-Corn Law League, and at the age of seven the young Robert reportedly heard the famous Quaker radical and Liberal statesman John Bright speak from the hustings at Durham.

Although he became a solicitor by profession, Spence Watson’s interests were many and varied and his work and achievements in the spheres of politics, social reform, philanthropy and education gained him a position of great influence and esteem in his native Newcastle and beyond. His entry in the Dictionary of National Biography states that he “represented the Quaker tradition of public action at its sturdiest”.

He was passionately interested in education and saw it as a means of improving an individual’s social condition. Amongst his many accomplishments in this area, he was Chairman of the first Newcastle school board and a pioneer of the Newcastle Free Public Library, ran working men’s Sunday classes and pioneered a system of adult schools. He was heavily involved in the foundation in 1871 of the Durham College of Science, later Armstrong College, which eventually evolved into Newcastle University, becoming its first President in 1910. He also served over a period of many years as Honorary Secretary, Vice President and later President of the Literary & Philosophical Society (Lit & Phil) in Newcastle.

A founder member and later President of both the Newcastle Liberal Association and the National Liberal Federation, Spence Watson was a lifelong adherent of the Liberal Party. Although he had no desire to enter the House of Commons, he was one of the most influential Liberal figures outside parliament. He had many high-profile political friends, many of whom he and his wife Elizabeth entertained at Bensham Grove, including the local Liberal MP Joseph Cowen, the afore-mentioned John Bright, Earl Grey and William Ewart Gladstone.

Spence Watson also cared deeply about the causes of those living under oppressed regimes. In particular he supported Russian political exiles in England, including Stepniak and Kropotkin. He was also well known in the North of England for his work as an arbitrator in trade disputes, which he undertook voluntarily, while he possessed a keen interest in literature and the history of the English language, and wrote a biography of his friend the pitman poet Joseph Skipsey.

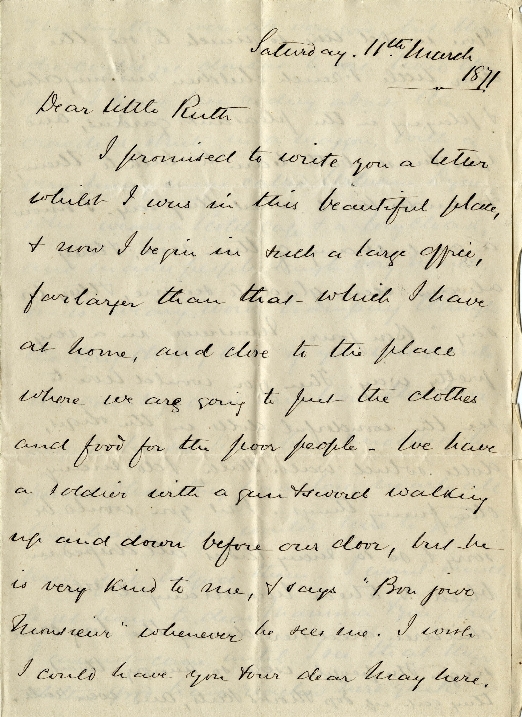

One of his most high-profile acts of public work came in 1870 when he was appointed by the Society of Friends (the Quakers) as one of the commissioners of its War Victims Fund, travelling to Alsace-Lorraine to oversee the distribution of relief to non-combatants in the French-Prussian War, many of whom had been left homeless, destitute and bereaved by the ravages of war in the region. When he returned to France in 1871 to carry out similar work for the French Government, he wrote this touching letter home to his four-year-old daughter, Ruth. In the letter, which is held in the Spence Watson/Weiss Archive (SW 3/10), he told Ruth of his work in France. Although he wrote with the gentle tone of a father to his daughter, it was clearly important to Spence Watson that his children were aware of the hardships suffered by those less fortunate than themselves, just as he himself had been aware as a child. The first page of the letter is shown below. He wrote:

“Dear little Ruth

I promised to write you a letter whilst I was in this beautiful place, & now I begin in such a large office, far larger than that which I have at home, and close to the place where we are going to put the clothes and food for the poor people. We have a soldier with a gun & sword walking up and down before our door, but he is very kind to me, & says “Bon jour Monsieur” whenever he sees me… you would like to see the wonderful dolls in the shops, dolls which walk & talk, & do many other funny things. But you would be sorry to see so many ladies all dressed in black, & to hear how many little children died here during the long cruel siege… I want much to get home to dear Mamma & you, but I cannot come until I see that their clothes & food have reached here quite safely.”