A student-curated exhibition based on work for a module on Radical Children’s Literature of the Early Twentieth Century. Curated by Rebecca Goor and Sam Summers, June 2014.

The period between 1900 and 1949 is one curiously overlooked when it comes to the history of children’s literature. It has been viewed as ‘an age of brass between two of gold’, referring to the two so-called golden ages of Victorian children’s literature that began with Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and post World War II writing by figures such as Alan Garner, William Mayne, Rosemary Sutcliff and Mary Norton. Books from this period have drawn criticism for their apparent ignorance of the changes occurring in the world around them, and for refusing to widen their focus beyond carefree middle-class children at a time when the struggles of the working class were increasingly a concern.

The writers and illustrators featured in this exhibition, however, were responsible for texts which, while not as well-known as the more conservative works of the period, tackled controversial themes, endorsed radical political views and thrived on aesthetic innovation.

The early twentieth century was a time of landmark political, military and social events which changed both Britain and the world at large forever. Two world wars, the depression, and the end of empire dislodged the United Kingdom from its seat of global power, and confronted the public with an acute awareness of the horrors humankind was capable of inflicting upon itself. At the same time, left-wing political ideals were gaining momentum with both the advent of communism in Russia and the steady rise of socialism in Britain.

In the wake of these large-scale cultural shifts, radical authors created a body of literature which challenged earlier notions of what a children’s book could be. They depicted a more diverse range of characters than the typical white, middle-class children of their predecessors, while also engaging their readers politically. Their books were more socially aware than those that had come before, challenging authority and questioning the dominant views of the day rather than deferring to them. Meanwhile, writers and illustrators whose work was not as thematically radical as some of their contemporaries were nonetheless creating aesthetically innovative books, with some incorporating modernist techniques into their writing and others displaying the influence of avant-garde movements in their artwork. The goal of many of these creators was to provoke change, by encouraging young readers to act on the ideas raised in their books to secure the future of the next generation of leaders and artists.

This exhibition highlights work from across the spectrum of radical children’s literature. It is divided into four sections: ‘Reacting to War’, ‘The Soviet Effect’, ‘Real Lives’ and ‘Artistic Innovation’. The examples are a reminder that across this time of cultural upheaval some children’s writers and illustrators were helping to prepare young readers to help bring about what they believed would be a more just, equitable, healthy and rewarding world for all.

Reacting to war

During the fifty year time period that this exhibition covers, war played a huge part in changing the social and political landscape not only in Britain but worldwide. Whilst the First World War (1914-1918) and the Second World War (1939-1945) were undoubtedly the largest conflicts during this period, other crises such as the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) contributed to the atmosphere of political instability. The relationship between war and Western children’s literature is often remembered as one that saw books inspire young readers to support the war effort by presenting life in the military as heroic and adventurous. However, as this exhibition aims to show, there were alternative works of children’s fiction between 1900 and 1949 that treated child readers as agents of political change, rather than as cogs in the war machine.

Many of the radical texts of this period were influenced by Socialist ideas, but other pacifist publications included those circulated by the religious group the Quakers and by progressive schools that believed in empowering children by inspiring leadership skills and independent thought. Whilst the left-wing literature movement in Britain was not strictly organised and consisted of various strands, some publications had significant followings; The Left Book Club, created by Socialist publisher Victor Gollancz, had a readership of 20,000 in 1936, increasing to 57,000 in 1939. The Junior Left Book Club encouraged children to read Socialist literature, demonstrating the power that reading held in inspiring new ideas in the younger generation.

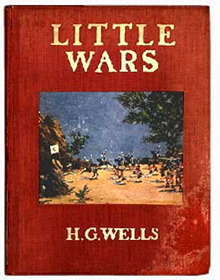

The four texts in this section include a non-fictional pamphlet, illustrated stories and even a rule-book for toy war games, demonstrating the range of opposition to militaristic children’s literature from this period, much of which has been forgotten in history. The earliest text of the collection, Little Wars (1913) by H.G. Wells, draws upon the child’s instinct to play to oppose militaristic values and expose the horrors of war. 20 Years After (1934) is a non-fictional pamphlet, providing a realistic depiction of the death and destruction caused by war, helping to counteract heroic, militaristic children’s stories that sentimentalise war.

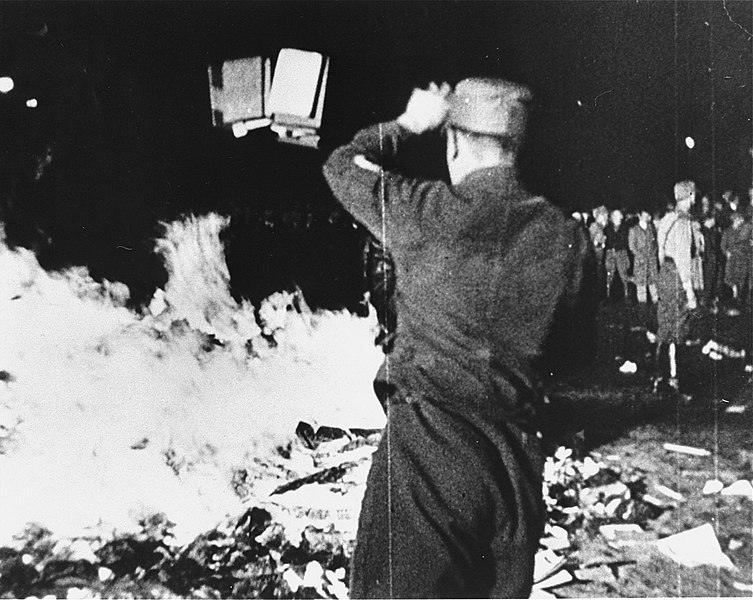

The collection also features two American publications, which show that anti-war messages were being communicated in America as well as in Britain. Johnny Get Your Gun (1936), the title of which plays upon the call often used in battle to rally troops, exposes the human costs of war through the paralysation of its soldier protagonist. The Story of Ferdinand (1936) carries a similar pacifist message, and despite its specific relevance to the Spanish Civil War, it extols opposition to fascism, which led to the book being burned by the Nazis. The range of texts in this exhibition exemplify the work of radical writers during this period that opposed the use of children’s literature for wartime propaganda, informing child readers about the horrors of war and presenting pacifism as a heroic alternative to militarisation.

Putting a stop to war games

Little Wars (first published 1913) by H.G. Wells is a set of rules for a table-top war game for children. Often considered the first popular handbook for war gaming in the English language, it can be said to have prefigured the later rise in miniature gaming and role-play, and even more recent developments in digital military games such as Call of Duty. The game includes rules for deployment, combat, movement and objectives, each of which is described in detail. The book’s full title is Little Wars: a game for boys from twelve years of age to one hundred and fifty and for that more intelligent sort of girl who likes boys’ games and books. Whilst this title reveals the book to be a product of its time in terms of gender stereotypes, Little Wars was radical during the time of its production due to its pacifist stance and universal message.

The book discusses the ‘death’ and ‘blood’ involved in warfare, but it does so as a way of opposing large-scale war in the real world. Wells distinguishes between the make-believe of the game and the reality of warfare asking, ‘How much better is this amiable miniature than the Real Thing?’ He capitalises on children’s instinct to play and compete in order to deliver his pacifist message, though the wide age range established in the full title suggests that these lessons were addressed to an adult audience.

H.G. Wells was an outspoken socialist and sympathetic to pacifist views, and this is reflected in much of his work for both adults and children. Paradoxically, Wells eventually supported British involvement in the First World War on the grounds that it

would be “The War That Will End War”. In other words, he felt it was necessary to resolve a range of tensions and areas of competition in order to create long-lasting peace and unity.

Wells’ socialist outlook as well as his then opposition to war is apparent in Little Wars. The game instructs players to use inexpensive materials, meaning that the book is suitable for children from all social and economic backgrounds. Little Wars, along with its predecessor Floor Games (1911), which similarly provided cheap role-playing games for boys and girls, widened the audience for children’s literature and toys, the majority of which still had a strong middle-class focus during the early twentieth-century. The universal message of the text suggests that in order to overcome militaristic and imperialistic values, people of all social classes must work together to create a more just society.

Like other texts in this section, Little Wars does not construct war as heroic but rather highlights the gore and suffering caused by warfare. Wells combines playful storytelling, hands-on play and a serious message to provide young boys (and possibly girls) with an opportunity to satisfy their competitive streaks without being manipulated into sacrificing themselves to the true horrors of war. Considered in hindsight alongside the horrific trench warfare that was to begin a year after the publication of Little Wars, the text is poignant in its attempt to educate potential soldiers about the truth behind the fictionalisation of war.

This image (above) was taken from a news article about the book with the caption ‘H.G. Wells, the English novelist, playing an indoor war game’. It shows Wells, a famous and respected literary figure, reduced to the level of his juvenile readers, reflecting his desire to educate them on their own terms.

Exposing the truth behind World War I

20 Years After! (London: Marston Printing Co., 1934) is a left-wing propagandist pamphlet written twenty years after the start of World War I and in the shadow of what was to become World War II. It exposes the largely unreported aspects of the first global conflict and rails against the injustice of the capitalist system in which a few individuals profited from the war to the detriment of the suffering masses. Socialist in outlook, the pamphlet was produced by the Youth Council of the British Anti-War Movement and distributed amongst left-wing groups with the aim of encouraging adolescent readers to oppose future war and fight against fascism.

The pamphlet attempts to engage young readers politically with its critiques of capitalism and fascism. It claims to expose ‘the real story’ of war and suggests the British Government is concealing the truth. Using facts and statistics to verify its claims, it tells a story of capitalists benefitting from industries facilitated by war whilst thousands lost their lives and suffered. These facts are simple to read, making the pamphlet accessible to the youth of all social classes, even those who were not experienced readers. Furthermore, 20 Years After! includes horrific photographic images that document the realities of war. One photograph features the mutilated face of a soldier and so underlines the shocking physical suffering and life-time disfigurement caused by the war. As a whole it suggests that readers would do better to band against war than to enlist.

The pamphlet gives the example of the USSR and its First Five-Year Plan as a way to counter war and fascism. Readers are told that the USSR has happier workers because of the increase in wages and investment in farming and therefore has no need for war. The implication is that following the USSR’s example would encourage peace. Furthermore, opposing fascism and war is portrayed as an international effort, through examples of other foreign congresses such as the Paris Youth conference in 1933. The pamphlet encourages British youths to become part of a worldwide pacifist movement, and urges them to understand that young people can influence the future of the world.

The pamphlet was published in 1934 and sold prior to the Sheffield Youth Congress with the aim of encouraging young people to join the anti-war movement. The realistic image of the tank reflects the aim of the pamphlet to expose the ‘real’ story and human costs of war.

The final page of the 20 Years After pamphlet invites child readers to become actively involved in pacifism by signing up to the anti-war movement. This approach is reflected in other radical children’s literature, in which the child is treated as an agent of change rather than a vessel for adult ideas.

Peace in the face of Fascism

Written in less than an hour by American author Munro Leaf and illustrated by Robert Lawson, The Story of Ferdinand (1936) remains one of the world’s best-loved children’s books. Before beginning his career as a children’s author – during which he wrote over 40 books – Leaf worked as a secondary school teacher in schools that were part of a progressive, student-centred form of education that encouraged leadership skills and independent thinking. Later, Leaf gave ‘Chalk Talks’ in schools across America, including lectures about world peace. Of all his activities it was this work of children’s fiction that provided the strongest and most enduring pacifist message.

At a time when much children’s literature served as war propaganda, The Story of Ferdinand features Ferdinand, a bull who refuses to fight in the bull ring. Although written during the escalating violence that lead to the Spanish Civil War (1936 – 1939), Leaf’s pacifist message has a more universal significance and was burned by the Nazis due to its anti-fascist sentiments. The story’s peaceful yet rebellious hero, Ferdinand, prefers to sit alone and smell flowers rather than fight with his fellow bulls. When he sits on a bee however, Ferdinand startled reaction is mistaken for aggression and his is taken to Madrid to be the star of the bull ring. The illustration of the bull-ring parade, with its flags and music, clearly references the collective passions associated with war rallies. Ferdinand challenges militaristic and masculine values when he refuses to fight in the ring, angering the Matador, whose thirst for blood is caricatured. Ferdinand’s gentle nature prevails, and at the end of the book he is able to return to his mother, and the flowers that he loves. Munro Leaf’s use of a bull – typically a more violent animal than those usually featuring in less radical children’s fiction – creates a challenge to authority that encourages child readers to obey their own instincts rather than blindly follow wartime hysteria.

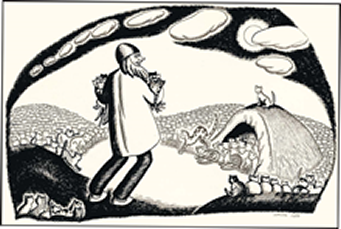

Robert Lawson’s illustrations are perhaps surprising for a children’s book, as the realistic black-and-white images lack the sentimentality associated with much children’s literature. In particular, the use of vultures creates a motif of death throughout the story that is not discussed in the textual content. The images provide greater depth to the narrative, whilst the discussion of such serious issues within children’s literature does not patronise children or shield them from reality. This radical text remains popular worldwide due to its universal celebration of peace and individuality.

The red front cover provides the only use of colour in this otherwise black and white text. In the later Disney adaptation of The Story of Ferdinand, the use of red survived, helping the cover to achieve international status as a pacifist symbol.

This image (above) exemplifies the wider motif of vultures throughout the text: something that is not discussed in the actual words of the story. Placing Ferdinand next to a height chart, with a vulture closely watching, explores the theme of death in a franker way than more conservative children’s literature. It is perhaps significant that Ferdinand avoids the final stage of death by refusing to fight in a military-like way.

Pushing past the propaganda

Johnny Got His Gun is an anti-war novel written for children over the age of 12 in 1938 when the approach of World War II was giving rise to widespread propaganda designed to persuade young men to enlist to fight for their country. The novel contrasts dramatically with more traditional pro-war children’s literature that has for long been associated with youthful enlistment. Dalton Trumbo’s radical – and powerful – novel questions the convention that soldiers are fighting for freedom. It also questions related constructions of liberty and the tendency to characterise the First World War as a game of ‘follow the leader’.

Johnny was radical as it challenged established ways of depicting war and military service and so undermined the conventions of traditional war stories for children. In such books men (and boys) who went to war were put on a pedestal and treated as heroic figures. Trumbo, however, opposes this image of a valiant figure fighting the enemy and instead confronts readers with the figure of Joe Bonham, who has had his arms and legs amputated and his face blown off on a WWI battlefield. His helplessness is reminiscent of a baby’s vulnerability, which contrasts with the strong and powerful image of men as depicted on propagandist posters. Trumbo wanted to represent the realities and horrors of war to prevent his young readers blindly following the previous generation to the front line. Like WWI, which saw many under age youths become soldiers, the novel blurs the division between childhood and adulthood by exposing young readers to the grim realities of war. As readers of this novel, they are treated as socially significant and rational beings, capable of deciding whether or not to join the war effort on their own.

Trumbo is far from subtle in his suggestion that fighting for freedom is a lost cause. Joe is anything but free in the novel, epitomising the ultimate enslaved man as he is trapped within his own body. He is unable to talk, walk, or even move; his injuries have made his body as helpless as a baby’s but he has the frustrated mind of a grown man. Joe’s injuries are extreme because Joe embodies the collective injuries of all of the soldiers. Surviving the war with injuries is presented as a fate worse than death. This highlights Trumbo’s views on the destructiveness of war. A soldier might never come home, or might come home injured, but neither situation conforms to the glamorised fantasy of war provided by propaganda.Throughout the text Trumbo contrasts the fantasy of war with the harsh reality of its horrors. Joe had a family and a lover waiting for him at home, as did so many other soldiers. There is no home or future for him on his return. This moving way of illustrating the consequences of war for many soldiers drives home the extent to which large numbers of people were devastated by the terrors and tragedy wreaked by World War I. In conveying his opposition to war in its every facet so unflinchingly, Trumbo breaks the conventions of war stories and encourages readers to think about the realities of war rather than accepting the myths generated around it.

The simplicity of the front cover reflects the book’s frank treatment of the injuries sustained by soldiers at war. Unlike government propaganda released around the time of the book’s publication in 1938, there are no images of heroic men to pressurise readers into sacrificing themselves to the war effort.

The Soviet effect

Between the two world wars, those involved in creating radical children’s literature were keen to engage young readers with the vast social experiment that was taking place in Soviet Russia. If it succeeded they believed the new social model being piloted there would offer a cure for the booms, busts and inequities of capitalism, imperialism, and patriarchy that had disenfranchised and oppressed huge numbers of people around the world, and which many blamed for the series of wars that had punctuated the first decades of the twentieth century. Radical children’s books treated events in the USSR as “The most exciting adventure in the history of the world” (An Outline for Boys and Girls and Their Parents, 1932) and depicted the emerging Soviet society as an ideal world in the making where children, childhood and youth were valued and given important roles.

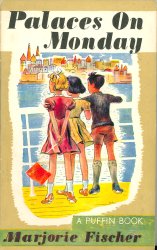

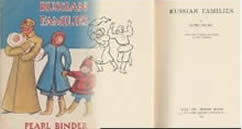

There were two principal ways in which radical children’s books introduced young readers to images of the Soviet Union. The first was through novels and fictionalised travel-writing by Anglo-American writers; the second was by translating and publishing some of the highly innovative picturebooks that had been published in the USSR. The six texts in this section represent both forms. Geoffrey Trease’s Red Comet: A tale of travel in the U.S.S.R. (1936) was written during a five-month residency in that country. Like Marjorie Fischer’s Palaces on Monday (1936), Trease’s novel features two children from the Depression-era West who have the opportunity to travel across the USSR. They visit parks of recreation and culture with their impressive facilities for children and admire the new ways of working and organising society. Both books are particularly concerned to tell their young readers about the egalitarian nature of Soviet society: divisions based on wealth, class, sex, race, ethnicity and even age are shown to be things of the past. Pearl Binder’s Russian Families (1942) also features many different aspects of the Soviet Union and gives an optimistic vision of how those who had previously been oppressed – peasants, women, and ethnic minorities – are thriving and contributing to their new nation.

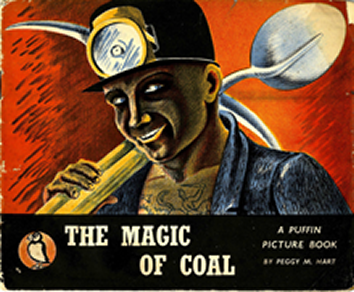

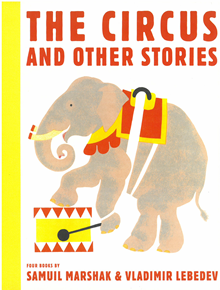

Picturebooks from the Soviet Union were remarkable for their stylistic and artistic innovation. Most of those translated for British children were written by Samuil Marshak and illustrated by Vladimir Lebedev. Yesterday and Today (1925) develops one of the themes most popular with the Soviet authorities. It compares the old-fashioned way Soviet citizens were living just a short time ago with the modern lifestyles achieved under the First Five-Year Plan. The Circus (1925), presented as a series of posters featuring different acts and artists, emphasises the dynamic and internationalist ethos of Soviet society. The influence of these books in Britain is evident in the last book in the section, Peggy Hart’s The Magic of Coal (1945).

Although disillusion with the Soviet Union set in as information about the shortages, famines, show trials and purges of the Stalin years became known, these books recall a time when radical children’s books in Britain were invigorated by both the aspirations of Soviet society and the artistically exciting children’s books created during the first years of the Soviet regime.

Bringing Soviet styles to Britain

This 1945 Puffin picture book entitled The Magic of Coal is an example of a wave of non-fiction picture books which entered the UK market for children’s literature in the 1940s, thanks to the efforts of Noel Carrington and Penguin Books’s Allen Lane. Influenced by the new Soviet ‘production books’ (books that told young readers about how everyday items are made and celebrated workers), these texts concentrated on themes such as farming, mining and other industries. Production books were part of the offical Soviet strategy to educate children about the advantages of their new communist society and the valued place of workers in it; children were central to Soviet policy and there are many examples of children’s literature being used to establish a public base for policies and plans. The Magic of Coal is the British equivalent of a Soviet production book in its focus on how things are made, its heroic treatment of miners, and its representation of a modern society in which social divisions are being eradicated.

The Magic of Coal introduces readers to the admirably technical and industrious world of coal mining. It not only tells how coal is produced but makes miners emblems of Britain – note the tatoo depicting St. George and the Dragon on the chest of the miner who appears on the cover. In doing so, the text and its illustrations point towards the political goal of making Britain a less class-riven, more equal society. To this end the book focusses on the production process rather than around any one character. Each role within the mine is shown through illustrations and accompanying text, implying that there is something for everybody. Every individual has a skill set to offer in the production of coal and is a valuable cog in the machinery of the mine. A sense of a community at work is created, and when combined with impressionist illustrations of tiny black figures and miners whose faces are blurred or have their backs to the reader, this sense of community solidifies into the socialist theory of collectivism. There are no visible owners or bosses and so it seems that the miners are working not in the service of capitalism but independently, for the benefit of the nation.

Improvements to working conditions also feature in this book which represents mining as a clean, modern, technologically advanced industry. The text informs the reader that the miners can attend the ‘pitbaths’ after work and rather show miners not begrmed with coal but looking rather like an office worker. Mention is also made of miners’ lives outside of work which include membership of societies, theatre visits and higher education. The Story of Coal, then, shows miners as lynchpins in a coal-fueled modern society, but also as respectable citizens with good standards of living and a thirst for culture. Miners are as important as the ‘treasure’ they dig up.

The battered state of the copy of Red Comet: A tale of travel in the U.S.S.R., which is missing its dust jacket, is typical. Few copies survive of either the 1936 edition published in the Soviet Union by the Co-operative Publishing Society of Foreign Workers or the UK and US editions that appeared the following year. The fact that it was first published in the Soviet Union no doubt contributed to the positive image of that country it paints.

First published in the UK in 1937, the image here is of the Palaces on Monday, Puffin edition published towards the end of the Second World War. It shows the three children with their backs to readers as they stare at the approaching coast of the country which represents their future. While the book emphasises Soviet building programmes the skyline shows tradition onion-shaped domes and tall spires.

Pearl Binder was closely tied to the Soviet Union and travelled there extensively. The illustrations in Russian Families, which she drew herself, give a sense of cheerful energy that matches her portrait of the country and its people.

The themes of this popular Yesterday and Today book capture the spirit of post-Revolutionary Russia. It celebrates ‘today’ in the form of the modern world while remembering the efforts of those who lived in the more difficult time represented as ‘yesterday’. The change is symbolised by the clothing and outdated objects of yesterday, drawn in black and white to contrast with the bright colours and modern equipment of today.

The images in The Circus book take the form of circus posters. Text and images both emphasise the international nature of the circus, with acts from many countries and people of different races and ethnicities all contributing to the performance.

Real lives

The first half of the twentieth-century is often considered to be a period of ‘retreatism’ in terms of children’s literature, and it is certainly the case that much mainstream children’s literature did maintain the status quo through its portrayal of white, middle-class families living comfortable lives unaffected by conflict or financial exigency. Radical texts, by contrast, acknowledged alternative ways of living and exposed child readers to poverty and the changing political landscape in Britain.

The period that this exhibition covers saw the emergence of the British welfare state, beginning with a basic National Health Service and Unemployment Insurance. The 1942 Beveridge Report, an enquiry into the best way to provide welfare in Britain, concluded that security should be provided for British people ‘from cradle to grave’. Legislation based on the report included The Butler Act of 1944, which referred to education, the 1945 Family Allowance Act and the 1948 National Health Act. Although social problems remained, these policies recognised the need to support working-class families and those living in poverty.

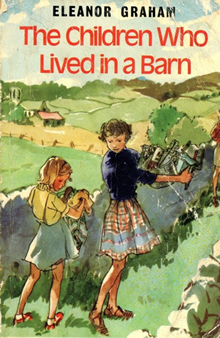

The earlier of the two texts in this section, The Children Who Lived in a Barn (1938), was written before the Beveridge Report and it demonstrates the need for increased governmental support through the analogy of incapable parents and adults who fail to provide for the children in the text. Child characters, on the other hand, are depicted as intelligent and self-sufficient. They show awareness of real-life issues such as money management, fear of eviction and loss of parents. By creating independent child characters, Eleanor Graham (the first editor of Puffin Books) foregrounds the role of the children’s writer as a figure that inspires children to engage with social problems and different ways of living, rather than one that aims to shield young readers from reality.

Whilst The Children Who Lived in a Barn exposes child readers to different characters than the middle-class protagonists often portrayed in children’s literature, Come In (1946) by Olive Dehn subtly raises questions about middle-class life and the consumer trend to build ‘ideal homes’. When asked to give an account of her day by her husband, who doesn’t understand why she complains about her life, Mrs Markham – a suburban housewife – tells a story of rigid routine, stress and dissatisfaction. Unlike in much children’s fiction, this picturebook does not present the middle-class home as a domestic ideal. By documenting the routine but demanding life of a middle-class housewife, Olive Dehn suggests that all is not well in suburbia.

By exploring issues such as poverty, the role of the state and gender politics within children’s literature, these radical authors encouraged young readers to seek solutions to the problems facing modern Britons. They refused to protect child readers from reality, encouraging them to question the world around them and strive for progress. Within radical children’s texts, children become central to achieving social change, meaning that they must receive contemporary information about the society that they live in. As this exhibition shows, radical children’s books were a key source of such information.

An unconventional adventure

Eleanor Graham’s The Children Who Lived in a Barn was the first Puffin Story Book. Like most books from the increasingly respected Puffin imprint, Graham’s book rapidly reached a wide readership and was admired in its day. Exciting and comic by turns, the story of the Dunnett children as they attempt to cope on their own after their parents’ disappearance is more than just a light-hearted adventure story. Graham fully describes the challenges her young characters face: being evicted, having to work and study and care for their new home (a barn) at the same time, and fending off social criticism and coming to terms with the increasingly distant possibility of their parents’ return. The story captures some of the tribulations of premature independence and heavy responsibility, themes that were shortly to come to prominence for many young evacuees in wartime Britain.

The emphasis and insistence on the children’s independence is striking in the text. Adults, who in children’s books are generally portrayed as a force of stability and security, are here largely presented as destabilising factors and even threats. The village women and District Visitor who aim to send the children off to orphanages are depicted as nuisances, and the landlord who evicts them is the clear villain of the story. Even the parents are not spared from criticism; they missed their airplane because they were buying stamps, forcing them to take a non-commercial plane which crashes. Their actions initiate the children’s troubles. It is in part due to such subversive thoughts that the book was published anew in 2001 by Persephone Books. In removing the original brightly illustrated cover and replacing it with a simple grey jacket, the new edition presents The Children Who Lived in a Barn as a modern text not just for children but for adults as well.

Whilst at first glance the cover of the text (see image above) is reminiscent of more conservative children’s fiction depicting tame countryside adventures, the children can be seen carrying their belongings as they begin to live unsupervised by parents. Even the youngest child, Alice, can be seen carrying pots and pans, emphasising the independence of the child.

The modern cover (published 2001) of the text is much simpler than the original and showcases the status of the text as an established classic that does not need flamboyant graphics. The seriousness of this cover also reflects the social message of the story and the potential for children’s writers to hold positions of authority in terms of child welfare.

The housewife speaks out

Olive Dehn’s superficially amiable book Come In (1946) in fact raises questions about the lives of suburban housewives and children in post-war Britain. The representation of a typical middle-class nuclear family in this picturebook emphasises some of the tribulations that came with being a mother at the time and the restraints on children’s ability to explore and experiment. Dehn was a life-long anarchist who lived a life very different from that of her characters.

Come In follows Mrs Markham, the mother, who complains about her dull life and is asked by her husband (an actor) to write an account of her day, so that he ‘could read exactly how dull it was’ (p. 2). Throughout the day the reader bears witness to the unending list of chores and challenges that Mrs Markham undertakes. She is the cook, cleaner and nanny, and appropriately is illustrated wearing an apron, and a black and white outfit that resembles the traditional uniform worn by maids in earlier generations. The whole text is punctuated by illustrations of, and references to, clocks. These show how regulated Mrs Markham’s day is, implying a machine-like routine, though without the order expected of a mechanised environment.

Mrs Markham is permanently in demand, hardly gaining a minute’s peace, whether it’s because her children and husband are continuously asking ‘where’s Mummy?’ (p. 7), or, because the phone or door-bell is ringing, there is another chore to be done, or somebody has had a minor accident. Whilst perhaps suggesting to young readers that they should appreciate their mothers’ efforts, there is also a slightly satirical tone, which perhaps only the adult reader would detect. References such as: ‘it’s time somebody began to think about getting dinner ready’ (p. 13), seem to be a wink to the mothers reading, as if to say, ‘I wonder who that might be?’ The book’s penultimate image is of the artist, who Mr. Markham has invited to draw the events of the day. As she walks away from the sleeping household she lights a cigarette and the two actions give a sense of independence and escape that the mother cannot attain. There is also an implicit sense that just witnessing the day is stressful enough to make the artist require a cigarette at the end of it.

Dehn challenges the expectation that being a 1940s housewife was a happy and rewarding role, and encourages her readers, whether children or adults, to see that new ideologies around home-making and child-rearing were highly restrictive. Just as their mother’s life is controlled by routine so too the children are shown as governed by a schedule and confined within clearly delimited spaces. Come In is less of an invitation than a threat; such a critical view of domestic life was highly unusual in children’s books of the period and so Come In sows the seeds of change radical change at the domestic level.

The inclusion of clocks in many of the illustrations emphasises how regimented the mother’s routine is. She runs like clock-work in an automated fashion, enforcing the idea that her life is composed and dominated by the time and everyone else’s separate routines.

Artistic innovation

The beginning of the twentieth century saw an aesthetic shift in both literature and fine art, including works aimed at children. The widespread social and economic change brought on by the Industrial Revolution and the First World War led to a rejection of traditional artistic values, particularly the nineteenth-century penchant for realism, which modernists and others involved in avant-garde activities regarded as outdated, limited and false. The modernist movement in literature saw the rise to prominence of authors whose work experimented with literary form resulting in texts which questioned the conventions of what a book could and should be. In the art world, expressionism championed the subjective over the figurative while surrealism revelled in the fractured logic of dreams, each challenging the notion that art must represent the physical world naturalistically.

These attitudes and ideas were taken up by children’s writers and illustrators in the first half of the last century. While often fantastical in their plots and settings, the majority of children’s books of the first ‘golden age’ presented their material realistically, with earnest prose and representative artwork. There were significant exceptions (notably Lewis Carroll’s Alice books), but the radical books produced during the period covered in this exhibition saw children’s literature pushing aesthetic boundaries in ways not previously seen.

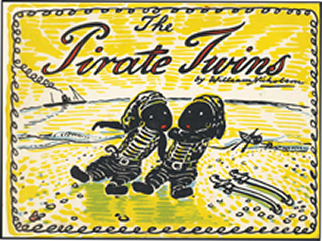

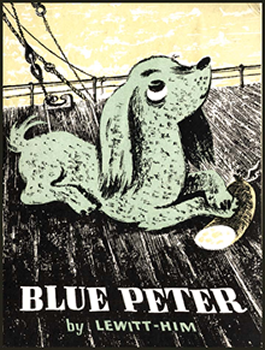

This section includes two picturebooks in which the illustrations reference modernist styles and movements. The Pirate Twins (1929) by William Nicholson and Blue Peter (1943) by the Polish émigré graphic artists who worked under the name Lewitt-Him incorporate elements of contemporary artistic movements including modernism, surrealism and expressionism. Both books play with the relationship between words and pictures in the manner of collage and sometimes giving rise to gaps and contradictions that open up new intellectual spaces in writing for children.

Also featured in this section is Stephen King-Hall’s collection Young Authors and Artists of 1935, a compilation of stories, poems, articles and artwork created by children themselves. In publishing the collection, King-Hall challenged the conventional relationship between the authors and readers of children’s literature, giving children free rein to write stories they would want to read rather than passively receiving work created by adults. Their work at times also displays modernist tendencies – which was in line with the modernists’ view that like primitive people children naturally saw the world in fresh and original ways. These three texts, then, together serve as an indication of the breadth of aesthetically innovative work being undertaken by those involved in producing radical children’s literature during the early twentieth century.

Created by taking over 93,000 still photographs of her cardboard silhouette characters and tinting each frame with colour, Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Achmed is the oldest surviving animated feature film. Her experimental style and enormous ambition are typical of the innovative spirit of the era.

One of the first modern picturebooks, Millions of Cats combined a simple, albeit surprising violent, narrative with fantastical images which blend the titular cats with the scenery to the point that they become difficult to distinguish.

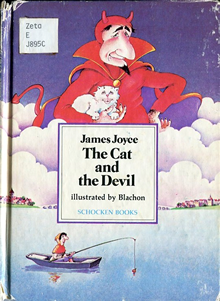

Originally penned as a letter from Joyce to his grandson in 1936, The Cat and the Devil is a retelling of a French folk tale was posthumously published as a picture book first in 1964 and again in 1981. While the story is a straightforward fable, a far cry from the radical innovation of his adult-oriented work, this nonetheless shows a prominent modernist author interacting with the world of children’s literature.

Redrawing the picturebook

The Pirate Twins (1929) by English illustrator William Nicholson was among the first wave of children’s picture books to employ modernist artistic styles and experiment with the relationship between words and pictures. Nicholson was a noted graphic artist, illustrator and engraver known for his visually innovative works; together his two picturebooks, The Pirate Twins and Clever Bill (1926), helped to change accepted ideas of what picturebooks could be. The Pirate Twins tells the story of Mary, who finds the titular twins on a beach, takes them home, and tries to teach them how to behave, only to find that they have little interest in learning.

Coming at a time when most picture books used illustrations decoratively rather than as part of the storytelling process, Nicholson’s books were innovative at the levels of both story and style. Neither its text nor its images can stand alone and thus turn what had been picture books into the interdependent picturebook in which words are incorporated into the pictures themselves, the colour of the text is changed to add emphasis to certain words, and the images sometimes depict important events unmentioned in the text. The Pirate Twins and Clever Bill demand a degree of interaction from their readers, asking them to read the words and the images in tandem and piece the story together themselves, rather than having it told to them in clear detail.

The portrayal of the anarchic, uncivilised twins hints at an anti-colonialist as well as a modernist agenda. Try as she might, Mary cannot ‘civilise’ the twins, and they eventually sail back to their home. This is seen as a happy ending, suggesting that people of other cultures cannot and should not be remoulded into the white British ‘ideal’. The twins’ spontaneity and original way of seeing the world also reflects modernist appreciation of ‘primitives’.

In this image, depicting the Pirate Twins alongside their friend Mary, highlights the stark difference in their depiction; the over-simplified, non-naturalistic aesthetic used to illustrate the twins marks them out as not only different but primitive when compared to the girl.

Illustrating inequality

Blue Peter uses a children’s picturebook to tell a tale of marginalised minorities at the time of its production during the World War II. Jan Lewitt and George Him were both Polish and Jewish, meaning that they had personal insights into the Nazi persecution of minority groups. The pair found themselves in London at the onset of war; there they discovered a network of artistic émigrés. Lewitt-Him as they styled themselves became known for their innovative use of strong colour, imaginative abstraction and symbolic surrealist graphics.

Their use of bold colour and minimalistic graphics can be seen in Blue Peter, as the titular dog is immediately recognisable as a minority through the visual contrast between the white fur of his mother and siblings and his own blue coat. Since the colour of his fur also informs his name, there is a suggestion that his colour constructs his identity. His mother even tries to bleach him white through fear that he will not be accepted by their master. However, the characterisation of Peter as a loveable puppy allows the reader to sympathise with his plight, and as is true of several of the texts in this exhibition, individuality is celebrated rather than condemned. Sailor Jeff adopts the abandoned puppy, stating that he has ‘always wanted a blue dog’, and giving rise to a series of adventures that sees Blue Peter become a hero.

Lewitt-Him’s illustrations take an expressionist approach to conveying the emotions of their protagonist; that is, instead of presenting the reader with an objective reality, the images are distorted for sympathetic effect. For example, in addition to highlighting Peter’s otherness in relation to his fellow characters, his blue coat is shown to reflect his state of mind; he is sad, or indeed ‘blue’. For readers of the book it is significant that Peter is colourful while his surroundings and the other characters are rendered drained of colour and variety. Sailor Jeff stands out because his shirt is also coloured blue.

The book’s innovative use of modernist graphics and surrealist elements departs from both the didactic tendencies of some politically radical writing for children and conservative works which shied away from including experimental artwork. Nevertheless, a socialist ideology of acceptance and unity prevails in the text, whilst the use of a minority figure as a heroic protagonist encourages children to embrace their individuality and carries a deeper political message at a time when the fight against fascism was a daily reality.

The expressionist bent in Lewitt-Him’s illustrations can be seen in these images, with Peter’s blue colouring contrasting with his monochrome surroundings, reflecting both his emotional state and his position as an outsider.

Children write back

Stephen King-Hall’s Young Authors and Artists of 1935 is one of a very few examples of writing for children produced by children. The book is a collection of stories, poetry, articles, and illustrations written and created by children and collected by Stephen King-Hall, who at that time had been a presenter on the BBC’s current affairs program Children Hour for five years. At the beginning of the book, King-Hall writes a foreword explaining that in his capacity as Editor of MINE, a magazine for children, he was sent many stories, poems and other kinds of writing by his young readers. This volume comprises the works he saw as displaying the most talent.

King-Hall was a radical thinker who was involved in politics, standing as an independent MP between 1937 and 1945. His political interests may have affected his selection of material, but evidently at least some children too were interested in topical issues. This can be seen, for instance, in the piece entitled ‘The Ruin of the Countryside’ which laments the pollution of the English country and ends with a dystopian glimpse into what the future might look like if the lack of environmental concern continues. Such examples of socially engaged pieces in the collection encourage readers to be socially aware and forward-thinking, and also to write about these social concerns and to make a change in society themselves.

The child authors show themselves to be alert to the conventions associated with material usually classified as children’s literature. For instance, one contribution reworks the well-known story of ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’ so that instead of porridge the bears eat fruit salad and at the end of story the whole thing is dismissed as nonsense because, of course, ‘bears don’t talk’. This rejection of traditional stories as well as the privileging of children as makers of their own literature functions as a form of ‘writing-back’ on the part of the contributors.

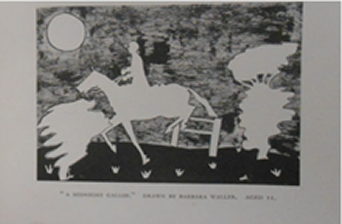

The illustrations in Young Authors and Artists were also created by children and are expressive, diverse and engaging. They disregard romantic childhood images produced by adults — for example sweetly innocent children playing nicely in pastoral settings and often make use of unusual visual devices such as the white silhouette in ‘A Midnight Gallop’. Together the works in the volume show the young contributors to be actively engaged in thinking about the world around them and innovative in terms of how to represent it.

The piece “A Midnight Gallop” (right) by an 11 year old girl contrasts the images of the foreground: the horse, bushes and the moon, with the dark background of the night. The polar opposite to a silhouette, these objects in the foreground are white instead of black.

Acknowledgements

The following students on the module ‘Radical Children’s Literature of the Early Twentieth Century’ contributed research and content to this exhibition:

Isabel Ashton, Ruth Bader, Louise Bartlett, Olivia Bland, Roderick Briggs, Sarah Bryan, Charlotte Burt, Lucy Campbell-Woodward, Hannah Carty, Salome Choa, Phoebe Clark, Alice Commins, Sarah Cripps, Rachel Davidson, Louise Dubuisson, Georgina Forshaw, Amy Fox, Ruby Gullon, Emily Hattrick, Jack Hawkins, Clara Heathcock, Michael Holden, Hannah Hunter, Esther Knowles, Imogen Lepere, Charles Lynch, Caroline Mackrill, Kerry Marshall, Alice Medforth, Heather Nicol, Francesca Nuttall, Helen Overton, Lucy Pares, Catherine Parkinson, Rebecca Pratt, Constance Richardson, Emily Seymour, Jennifer Smethurst, Angela Stone, Sam Summers, Jennifer Thynne, Rebecca Goor