Written by Robinson bequest student Becky Sanderson

Newcastle University Special Collections and Archives currently houses 972 transcripts which contain the detailed radio transmissions of day-to-day stories and science told by the members of the British North Greenland Expedition (BNGE) 1952-1954. The BNGE traversed north Greenland, exploring the great white landscape from Dronning Louise Land in the east, to Thule in the west. The team undertaking this feat ranged from glaciologists and geophysicists to naval wireless operators and naval medical officers. Within the team, familiar scientific names jump out including Stan Paterson, Colin Bull, Malcolm Slessor, James Simpson, and Newcastle University’s own Hal Lister.

Hal was an undergraduate student at Newcastle before, and an academic staff member after the expedition. Hal was also a member of many Antarctic missions and potentially one of the first people to overwinter in both Greenland and Antarctica. While on the expedition, he maintained his links to Newcastle University when applying for a Shell Studentship. Hal needed the reference of a senior academic at his institution and reached out to Professor Henry Daysh (head of the Department of Geography, now School of Geography, Politics & Sociology, up until his retirement in 1966).

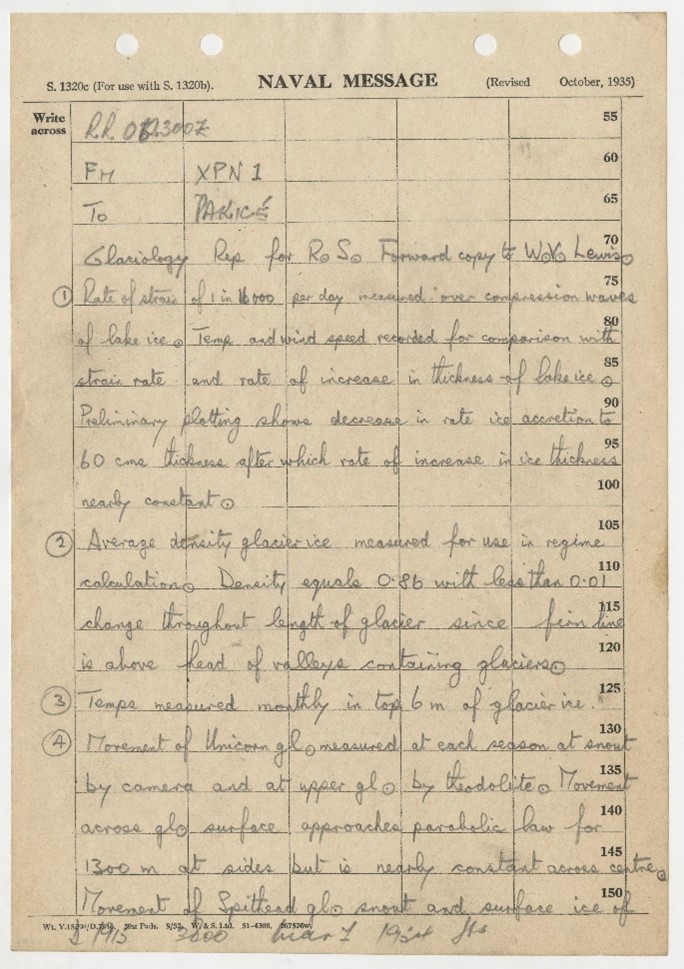

My interest in the archive is driven through my love of glaciology. I am currently undertaking my PhD within the Physical Geography department at Newcastle University focusing primarily on Antarctic research. Therefore, my knowledge of the archive was very limited until reading the 1957 book ‘High Arctic’ by Mike Banks (one of the expedition members) and delving further into the archive. I was given the opportunity to transcribe and order the transcripts through the Robinson Bequest Bursary. Before I begin, my understanding was that I would be trawling through hundreds of pages of scientific reports and findings. However, much to my delight, not only does the archive contain scientifically important datasets, methods and polar expedition logistics, but the archive also contains heart-warming Christmas messages (Fig. 1), birthday messages, notifications of the birth of family members, requests for alcohol and cheese and many jokes about how cold the temperature is in the Arctic.

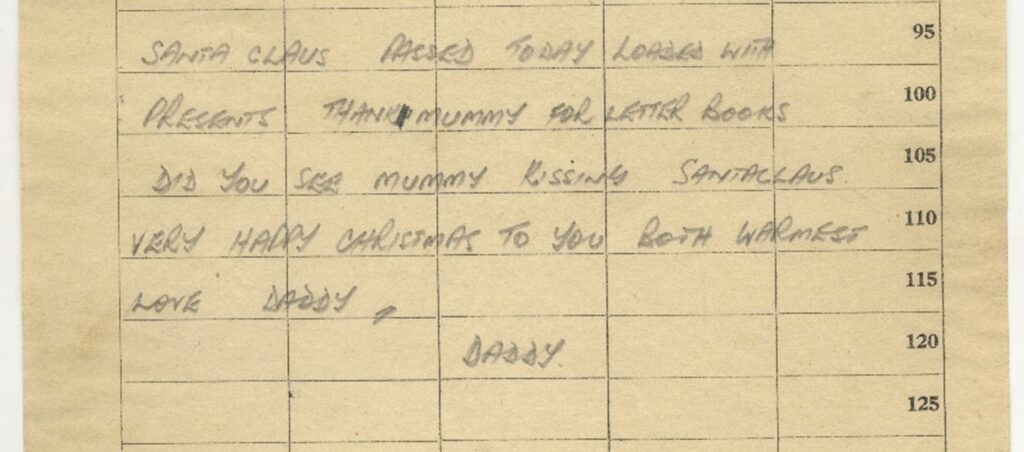

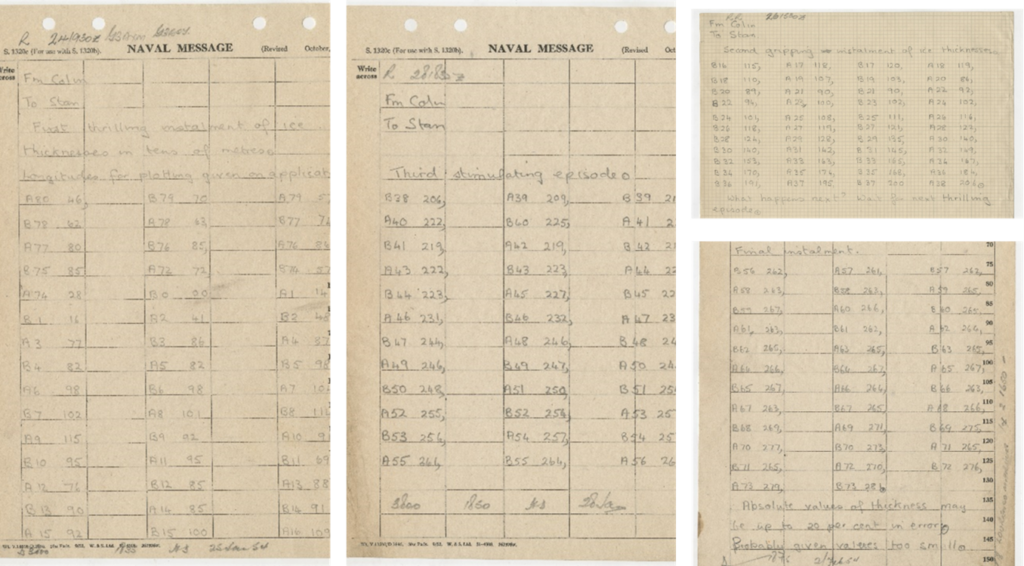

Overall, the BNGE was a huge success. The research findings and data collected on the expedition (Hamilton, 1958 and references within) have contributed to long term quantification of ice sheet change studies (Paterson and Reeh, 2001) and generated scientific questions that are still relevant for those researching the ice sheets today. The way scientific findings were communicated through the transcripts vary from detailed glaciology reports (Fig. 2), to the self-proclaimed “trilling instalment” of direct measurements of scientific information (i.e. ice thickness: Fig. 3). Not only this, but throughout the expedition, the team built up strong international collaborations with the Americans, Danes, French, Australian and the Icelanders. By doing so, they were able to share and gain information on safe passage, weather reports or general advice. The successful logistic operation of the expedition is worthy of note. The partnership between those on the ice and the RAF worked effectively and efficiently. The RAF provided support from the air throughout the two years on the ice. The relationship flourished so well that the RAF dropped a Christmas hamper for those at main base in the first year.

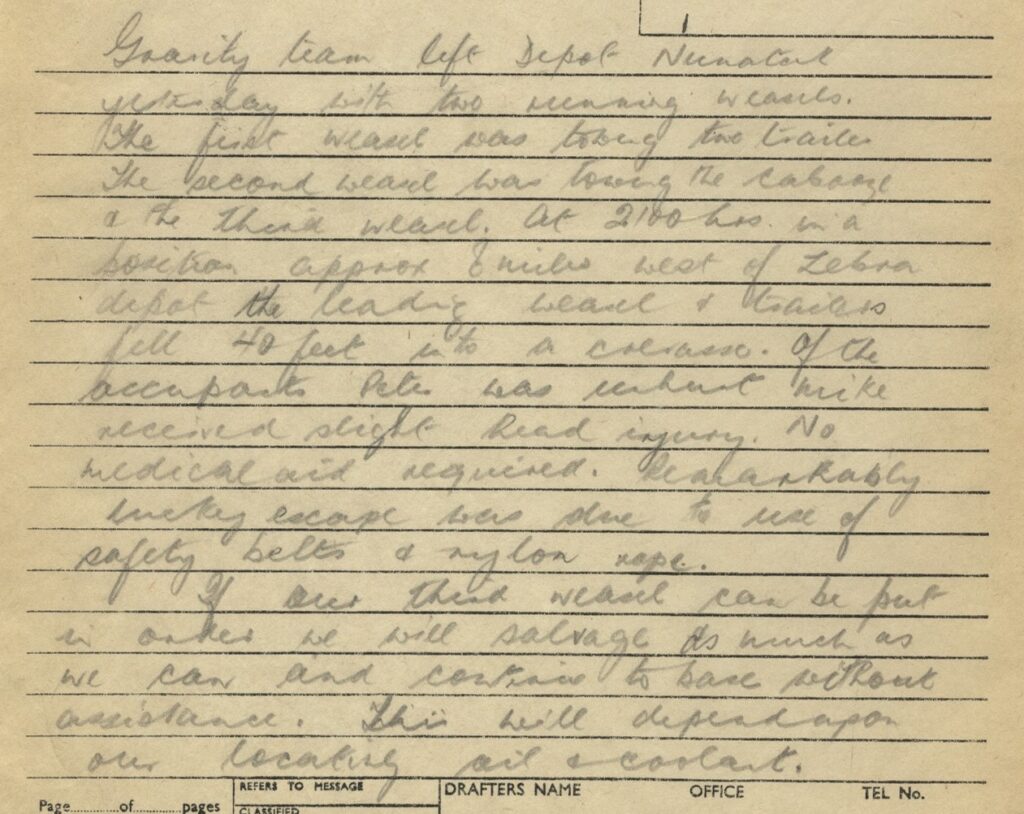

I have mentioned the huge success of the expedition, however, most polar exploration does not go without a few hiccups. For those on the BNGE expedition, there were certainly a few hiccups. Polar expeditions are often highly dangerous and the challenges that the team faced is highlighted throughout the transcripts. Although no specifics are recorded, the transcripts detail the gratitude of the family for the support they received after the death of Danish team member Captain Hans Jensen. Hans was the only fatality, however, there were several other “lucky escapes”. Weasels (snow tractors) often broke down in the middle of the ice sheet, exploded or fell into crevasses (Fig. 4). There were other incidents of fires breaking out in the engine room of their huts and bases. However, one of the most notable disasters was the “Ice Cap Crash” of 1952, that even made BBC news at home in the UK. Video footage of the crash site and drop operation was captured in this Ice Cap Men Return From Greenland (1952) video.

A large portion of the transcripts detail the rescue plans and effort of the members on the ice, the RAF and the collaborators at the American base in Thule. The rescue took eight days, the three injured members of the aircraft crew made a full recovery in the hospital in Thule.

The BNGE was one of few scientific polar expeditions that took place in the mid-20th century and can be viewed as the inspiration for many internationally important scientific and geophysical investigations that followed. The knowledge and experiences gained by those on the expedition has moulded our understanding of the physics of ice sheets. It has also shaped the way that I view my own work, the incredible challenges that the team faced in the field are often now taken for granted because of technological advances. It has been a privilege to read through the personal accounts of each members experiences and the uplifting messages that they were able to send home.