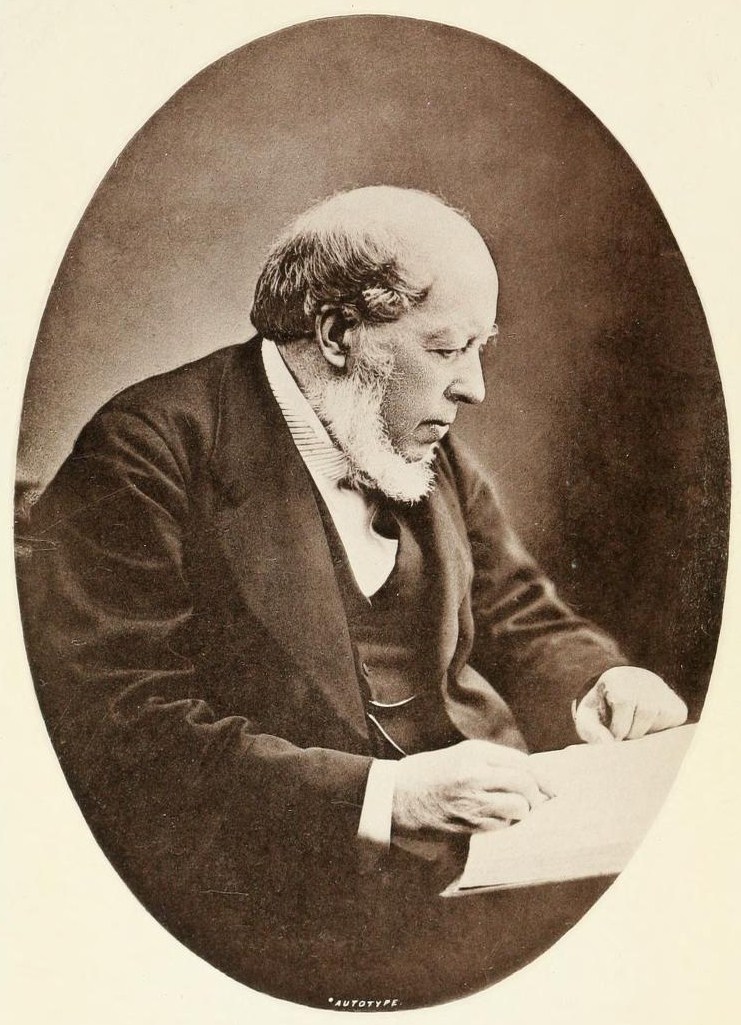

Thomas Sopwith (1803 – 1879) was an English mining engineer, land surveyor and philanthropist. His diaries cover the period from 1828 to 1879 and detail his work, projects, and travels.

In his own words, Sopwith often “spent a leisure hour very pleasantly in writing down a few memoranda which should serve in future years to recall the scenes of the past with greater clearness than the memory unassisted could do”. It was with this intention that he chose to describe, in exacting detail, the contents of his Writing Room, “in which so many of my hours are passed with a degree of enjoyment which it would be difficult to surpass”.

Inside Sopwith’s Writing Room

In an entry dated 25 December 1838, Sopwith meticulously records the contents of his Writing Room. To his left, a warm fire glows, the mantle above it crowded with geological specimens, fossils, and inkstands. Above the mantle hangs a “very pretty” looking glass and a gilt-framed watercolour of Greta Bridge in Keswick.

The remaining walls are adorned with engravings, watercolours and oil paintings, including a portrait of William M. Pitt esq, purchased by Sopwith on a ‘very delightful excursion’ with Pitt at his seaside house in Swanwick.

The contents of Sopwith’s closets and bookcases are itemised with immense care; each one seemingly overflowing with books, prints, and neatly arranged mineral collections.

Beside the window sits a piano belonging to Sopwith’s wife, Annie, whom he fondly refers to as his “better half”. He notes that in amongst these treasures “are some things apparently trifling but which I highly value” including a portrait and a “handsome gold purse” given to Sopwith by his wife.

Christmas at the Sopwith’s

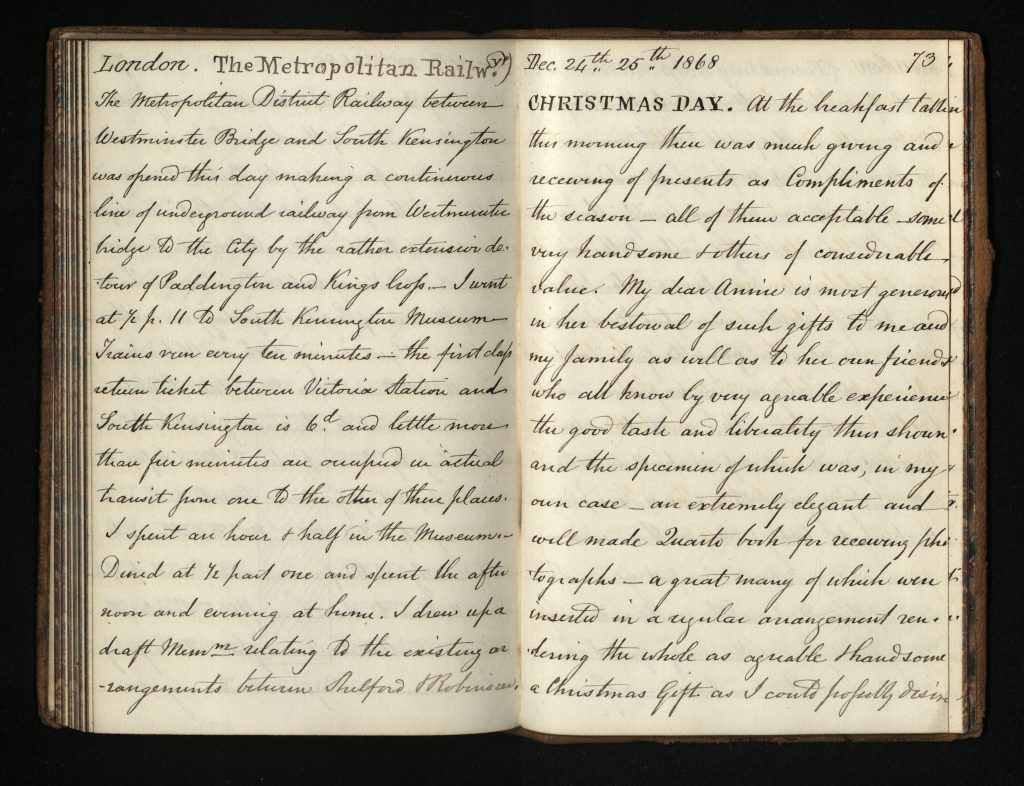

From the 1860s onward, Sopwith begins to offer richly detailed, almost hour-by-hour accounts of Christmas Day in his diaries. These entries provide a vivid account of a privileged Victorian household at the height of the festive season.

Like most mornings in the Sopwith household, the day began with breakfast:

“At the breakfast table this morning there was much giving and receiving of presents and Compliments of the season – all of them acceptable – some very handsome & others of considerable value. My dear Annie is most generous in her bestowal of such gifts to me and my family as well as to her own friends, who all know by very agreeable experience the good taste and liberality thus shown and the specimen of which was, in my own case – an extremely elegant and well made Quarto book for receiving photographs — a great many of which were inserted in a regular arrangement, rendering the whole as agreeable & handsome a Christmas Gift as I could possibly desire.”

After breakfast, the family would attend the Christmas Day service at the Foundling Hospital in Bloomsbury, where Sopwith found the music “deeply impressive” and “remarkably well performed”. When possible, he would also visit Westminster Abbey for afternoon prayers, though once noted it was “so densely crowded” that he had to stand for the entire service.

The remainder of the day typically involved visiting friends and acquaintances, followed by luncheon with a Mr and Mrs Routledge in Russell Square. Candlelit Christmas evenings, unless “spent quietly at home” as in 1870, were filled with dinners, dancing, and “other amusements”. In 1868, for instance, Sopwith dined and “spent a most lively and pleasant evening at Mr T. M. Smith’s, No. 1 Chapel Place”. He describes it as “a most hospitable entertainment,” where guests danced and sang “Canny Newcastel,” “Auld Lang Syne,” and concluded, naturally, with “God Save the Queen”.

A Portrait of Victorian Private Life

These warm and detailed descriptions offer a glimpse into Sopwith’s private world. Though he is remembered today for his contributions to science and engineering, his diaries reveal the quieter moments of his everyday life. A breakfast table covered in cards and parcels, a thoughtful gift from a beloved wife, gatherings of friends and loved ones. Together, these gentle details depict a portrait of Victorian private life, and connect us, across the centuries, to the familiar rhythms of home, family and friendship at Christmas.