From the streets of Sunderland to the steps of Whitehall: Origins of the role of chief medical officer

The outbreak of cholera in Sunderland in 1831 brought about the catalyst for the UK Government to begin thinking seriously about the health of the nation.

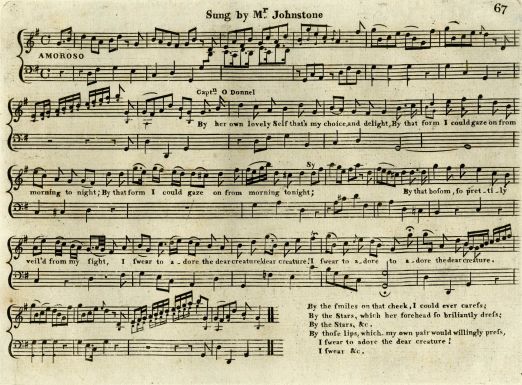

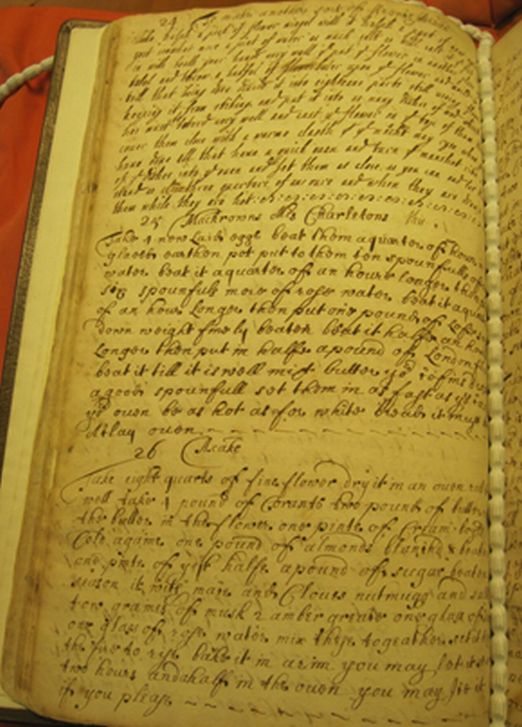

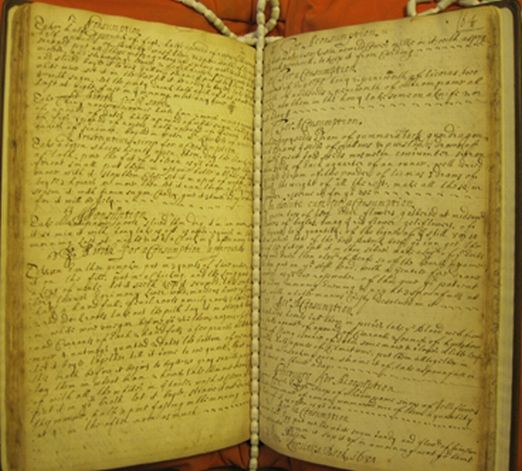

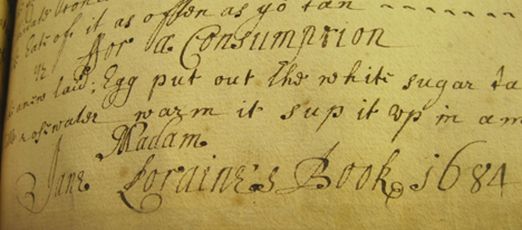

(Rare Books, RB616.932 BEL)

Public health champions with local connections (including one of the first and most famous alumni of Newcastle University) brought scientific approaches to preventing disease and raising awareness of the hazardous conditions the majority of the population lived in. It was these breakthroughs that led to the first Public Health Act of 1848 and the first Chief Medical Officer to advise the Government on Public Health issues in 1855.

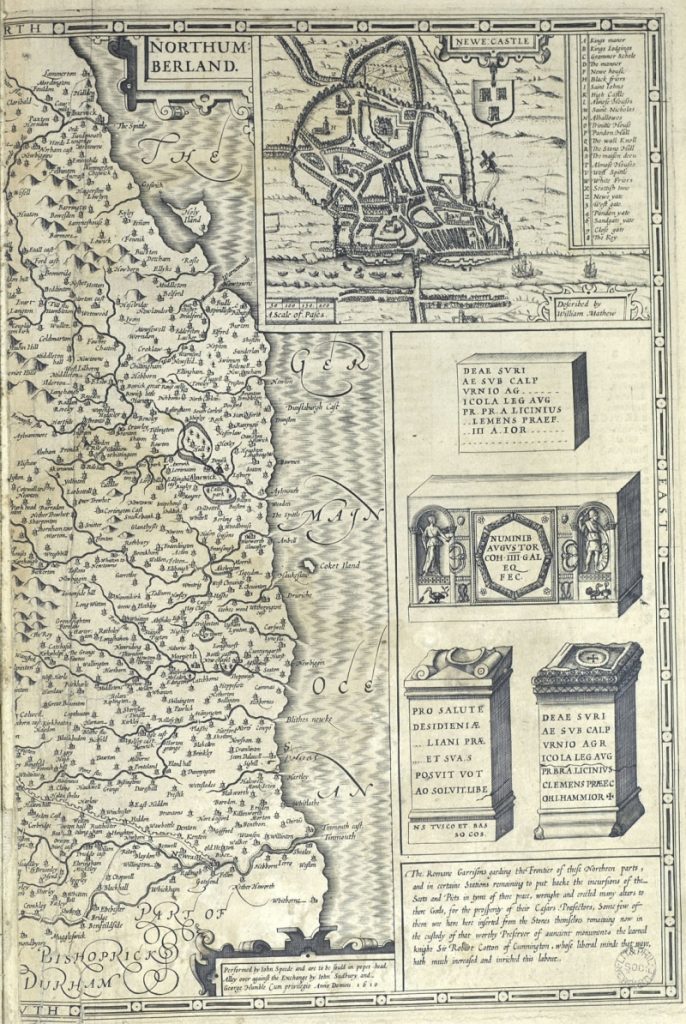

King Cholera enters England via Sunderland

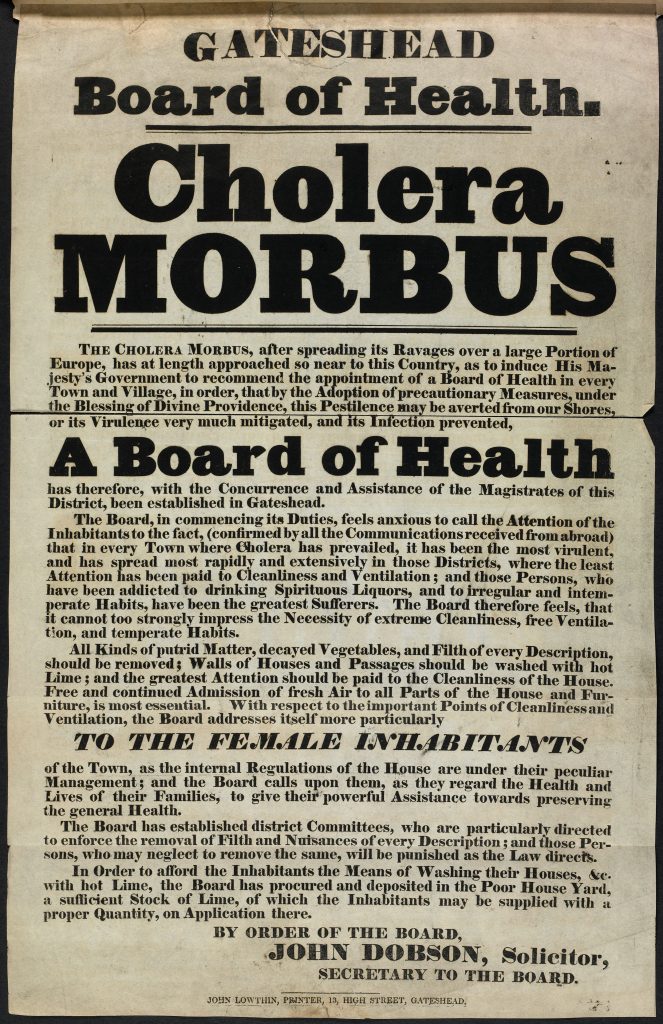

Prior to 1829, “Cholera Morbus” epidemics had been isolated to India and Asia, killing hundreds of thousands, including British soldiers posted abroad.

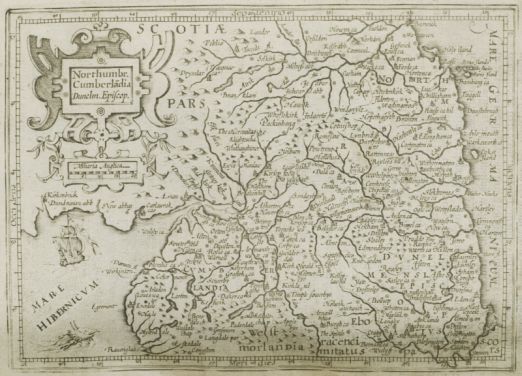

It is now known to be a bacterial disease caused by contaminated food and water supplies. Because of its major ports and trade centres, as well as poor sanitation and living conditions, it was the North East that first experienced Cholera in this country, which went on to kill an estimated 55,000 nationwide.

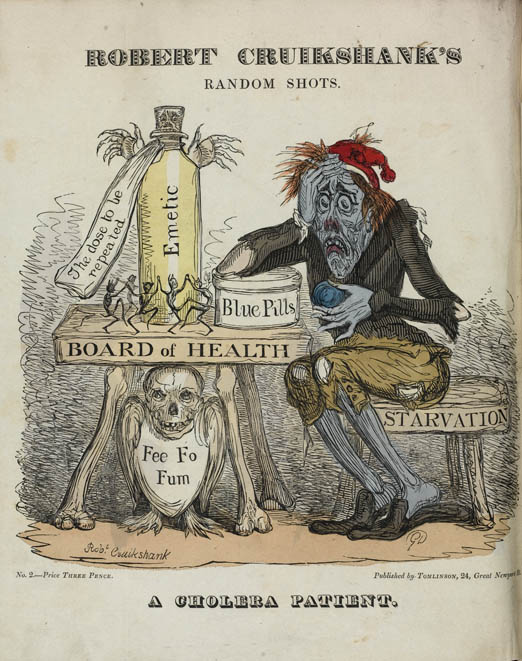

The first victim died on 23 October 1831 in Sunderland and it quickly reached Gateshead and beyond. Because of a lack of local or even central disease control, the causes of cholera were largely misunderstood even with the establishment of Local Boards of Health in badly affected areas and its spread was not properly addressed. The reign of “King Cholera”, became a call to action for the Government and medical profession to work together in order to protect the health of the population.

Cleaning up towards a public health act

Through the culmination of the pioneering Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain in 1842 by philanthropist and civil servant Sir Edwin Chadwick (1800-1890) and a fresh outbreak of cholera in 1848, claiming 52,000 lives, poor sanitation in England became the focus of the Government’s efforts to curb disease epidemics. These were sound assumptions; sewerage, water supplies and housing were largely inadequate and “nuisances” such as refuse and animal waste in the streets, made the lives of the general population hazardous and short. The average life expectancy was 40 in the 1850s and as low as 26 in some urban areas.

Chadwick himself was instrumental in the passing of the first Public Health Act in 1848; a major milestone. Its aims were to improve sanitation through the creation of a General Board of Health and provision for Local Boards of Health to oversee reforms. These could be imposed by the General Board if death rates in an area exceeded twenty-three in a thousand. Although these institutions were largely overworked and underfunded and had little remit beyond sanitation, they succeeded in bringing the true plight of the working people of England to the attention of the policy makers.

Chadwick himself was instrumental in the passing of the first Public Health Act in 1848; a major milestone. Its aims were to improve sanitation through the creation of a General Board of Health and provision for Local Boards of Health to oversee reforms. These could be imposed by the General Board if death rates in an area exceeded twenty-three in a thousand. Although these institutions were largely overworked and underfunded and had little remit beyond sanitation, they succeeded in bringing the true plight of the working people of England to the attention of the policy makers.

A first class answer to cholera

The roots of the cholera epidemic can be traced back to the North East, but so can the solution to its cause and prevention.

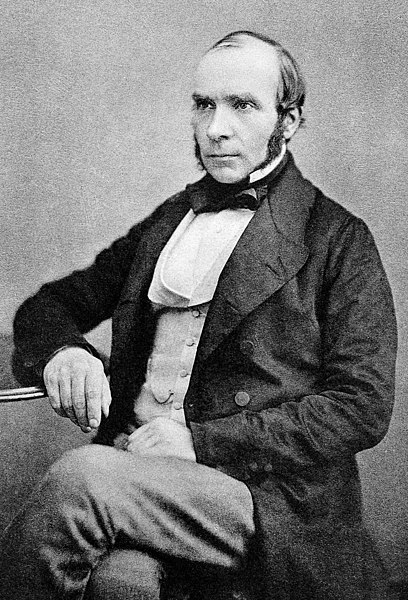

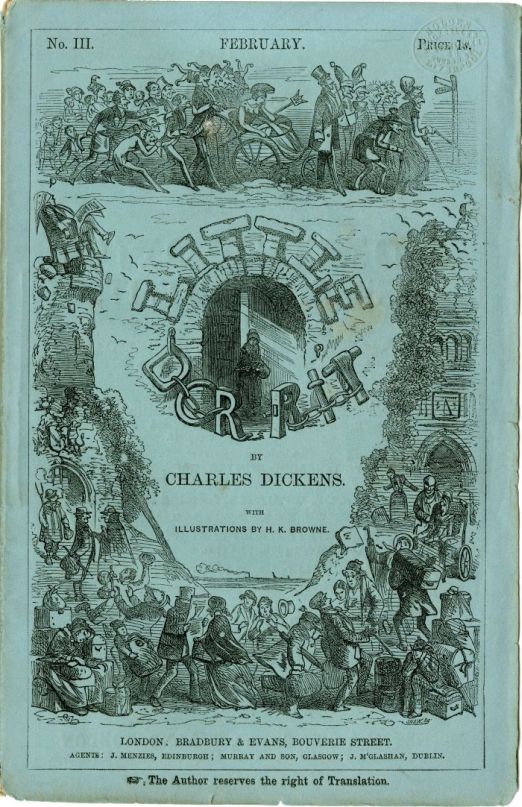

When the first School of Medicine and Surgery opened in Newcastle in 1832, which the University as we know it emerged from, one of the eight students was a John Snow (1813-1858), an apprentice to a surgeon in Benton. He attended to the poor during the cholera epidemic, witnessing the disease first hand; an experience that was to define his medical legacy.

In 1849, Snow published the groundbreaking work On the Mode and Communication of Cholera theorizing that it was in fact a waterborne infection. He built on this through statistical experiments which proved that an 1854 cholera outbreak in Broad Street, London was caused by contamination of the water pump. Snow’s scientific research techniques into evidence, patterns and prevention identify him as one of the fathers of Epidemiology; the cornerstone of Public Health medicine.

Branching out: evolution of the Chief Medical Officer

The value demonstrated by Sir John Simon in the role has made the post of Chief Medical Officer an enduring one to date, but also one of the most difficult and misunderstood. For over 150 years, those charged with protecting the Nation’s Health have overseen multiple health crises, scientific medical breakthroughs, the birth of the NHS, and a more parental attitude towards the population’s well-being.

Through these challenges, they spoke as the head of the medical profession, chief independent advisors to the Government on all medical matters, but, above all, the Chief Medical Officers had to act in the interests of the public’s health.

Such a balance required strong personalities with both the medical expertise and diplomacy required to push through reforms for the greater good. 13 of these are profiled on this diagram of Chief medical Officers on 1876-1998.

Healthy roots, local soil

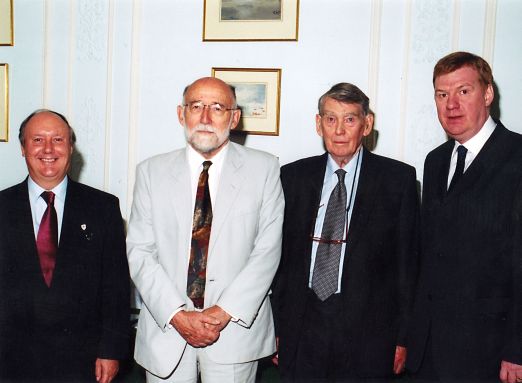

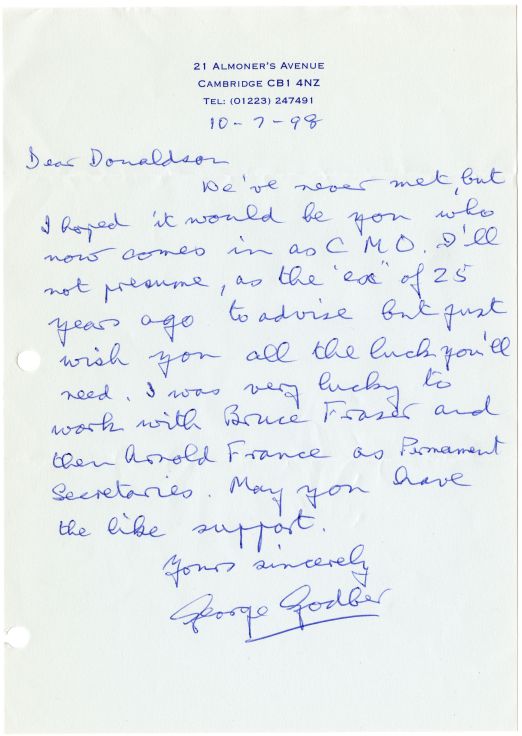

Sir Liam Donaldson was born in Middlesbrough in 1949 into a medical family. His father Raymond “Paddy” Donaldson (1920-2005) was himself a Public Health champion and a local Medical Officer for Health in Rotherham and later Teesside. Like the first Chief Medical Officer, Sir Liam initially opted for a career in surgery, gaining a Masters degree from the University of Birmingham in Anatomy.

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/5/5/1].

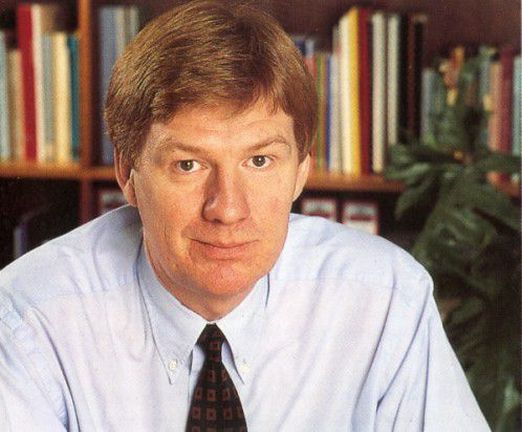

After 2 years as a Surgical Registrar and teaching and research posts in the Midlands, gaining his Doctorate in 1982, Sir Liam changed his speciality to Public Health so his work could impact on populations rather than just individuals. He honed his skills and understanding of the discipline as a General Practitioner, but continued to be a force in academic medicine, including becoming Professor of Applied Epidemiology at Newcastle University in 1989.

A Chief Medical Officer in the making

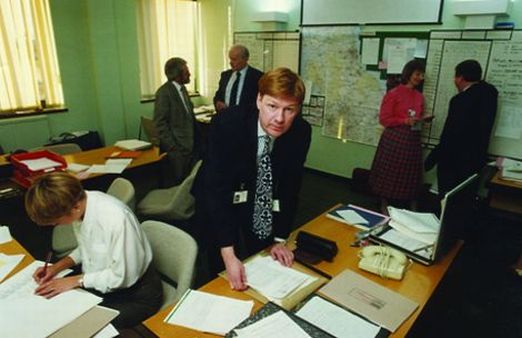

It was in the North East that Sir Liam was able to gain the vital experience in Public Health Management that would ready him for the top job as Chief Medical Officer.

[Donalson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/1/2/3]

In 1986 he became Regional Medical Officer to the Northern Regional Health Authority, progressing to become Regional General Manager and Director of Public Health. He continued in these roles when the Northern and Yorkshire Regional Health Authorities merged in 1994, becoming responsible for the health needs of some 7 million people.

During this period, he responded to high profile local crises which received national media coverage, such as the Cleveland Child Abuse scandal. Sir Liam formative years also gave him the opportunity to develop the health agendas that would define his career.

c. 1998,

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/5/3/9]

A firm believer in the importance of high clinical performance, he is credited with the invention of Clinical Governance as a means of constant improvement in health care standards. He also successfully reduced waiting lists and created strategies for improving the health care and quality of life for local people.

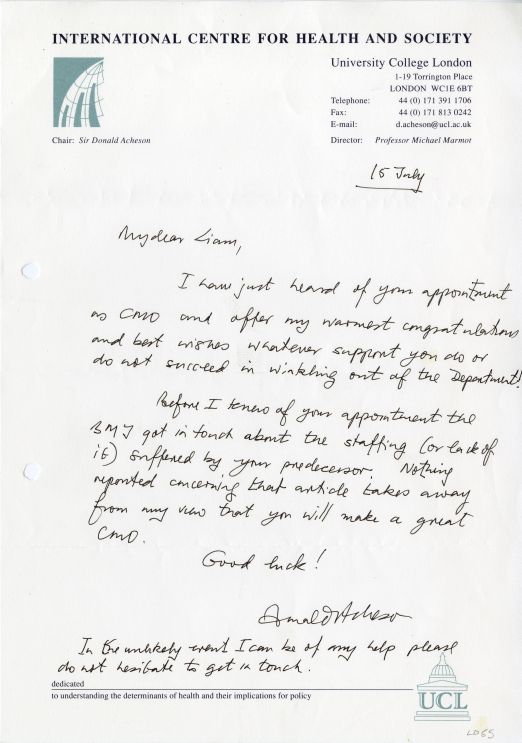

Sir Liam’s initiatives during his 12 years in the North led to him to become the leading candidate to be Chief Medical Officer for England when Sir Kenneth Calman stepped down in 1998.

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/5/3/4]

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/5/3/8]

Without fear or fervour: the 15th Chief Medical Officer for England

Sir Liam’s time at the Department of Health was one of major reactive and proactive reform shaped by his vision of improving the health of the population.

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/3/9/9]

Among his many achievements were the ban on smoking in public places, regulated stem-cell research, improvements to infectious disease control, and new systems to prioritise patient safety in the UK.

Acting as the bridge between Government and medical practitioners, he responded to high profile criticism of his profession through better safeguards. His trailblazing annual reports and significant campaigns meant he was also able to further his own health agendas for action on poor lifestyle choices, high quality health care and patient centred medicine.

The fire fighter: responding to crises

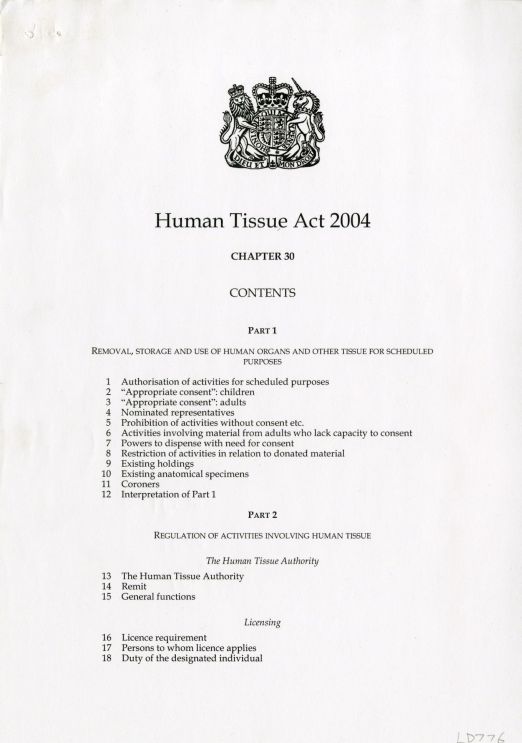

(London: HMSO, 2004),

[Donaldon (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/3/3/8/35]

When a public inquiry in 1999 revealed that a large number of hospitals, notably Alder Hey Children’s Hospital and Bristol Royal Infirmary, had retained patient’s organs and tissues without family consent, Sir Liam was charged with leading the Government response. He commissioned a census to determine the scale of the problem and made significant recommendations for reform. These led to the Human Tissue Act 2004 to ensure the wishes of the deceased and their relatives came first.

Donaldson, L. Good Doctors, Safer Patients: Proposals to Strengthen the System to Assure and Improve the Performance of Doctors and to Protect the Safety of Patients

(London: Department of Health, 2006)

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/3/3/16/20]

A parallel crisis which similarly damaged public confidence in the medical profession was the murders carried out by Dr Harold Shipman. Sir Liam first established, through an audit of Shipman’s clinical practice, that he was likely to have been responsible for between 200 and 300 deaths. His response was to target how doctors were regulated and continually assessed. His recommendations formed the basis for changes to the General Medical Council and complaints procedures.

As early as 2004, Sir Liam had predicted the inevitability of a new strain of influenza becoming pandemic.

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/3/3/11/20]

His work established the Health Protection Agency to lead responses to such outbreaks and those caused by bioterrorism. His extensive preparations and awareness campaigns proved well founded when in 2009 the H1N1 ‘Swine Flu’ virus became pandemic. Sir Liam put his plans to step down as Chief Medical Officer on hold to coordinate the response and was commended for his key role in lessening the potential impact.

The communicator: on the sate of the nation’s health

Annual Reports had been used to highlight the nation’s health issues since Sir Johns Simon’s first in 1858. Sir Liam aimed to write more accessible reports for a wide audience targeting the most serious problems with clear action points. These 9 influential reports led to considerable media coverage and both policy and legislative change.

Donaldson, L. (London: Department of Health, 2003, 2007, 2009),

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/3/2/2/2; LD/3/2/6/3; LD/3/2/8/2]

Sir Liam’s repeated call for smoke-free public places and workplaces led to legislation being passed on 1 July 2007 with this outcome for England; a true public health landmark. By 2009, all cigarette products were also required to carry explicit health warnings.

He also continually drew attention to the damaging effects of poor lifestyle choices, such as obesity. He promoted the need for regular physical activity, which led to major policy changes and awareness campaigns on diet and well-being.

Similarly, Sir Liam produced guidance on the consumption of alcohol by children and young people in 2009 based on scientific research in an effort to change the way families view and use alcohol. His call for minimum pricing on alcohol was rejected by the Government in the same year; a move they were heavily criticised for. The fact it remains a policy agenda is testament to the value of Sir Liam’s tireless campaigning for the good of the Nation’s Health.

The Reformer: New Branches

As Chief Medical Officer, Sir Liam wasted little in time in developing his concept of Clinical Governance; this means of measuring and continually improving on the performance of medical practioners and excellence in health care. His publications paved the way for the establishment of National Clinical Assessment Authority to monitor competency and, through statutory reforms, the NHS was required fot the first time to continuously improve the quality of their services.

27 Jul 2000

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/3/3/9/4]

At the heart of this like much of Sir Liam’s work, was the safety of patients where poor standards meant unnecessary risks. He identified the deficiencies in reporting, investigation and learning from mistakes as key to the problem. In 2002, the National Patient Safety Agency was created to collect data and encourage such reporting in order to prevent accidents happening again. Through reforms, the UK became a world leader in patient safety.

Under Sir Lian’s leadership, the scientific community also benefitted when he reviewed and made recommendations for less restrictive stem cell research. After consultation, he concluded that the potential to develop new tissues for a wide range of diseases and disorder through theraputic cloning was warranted. This laid the foundations for amendments to the Human Fertilisation and Emryology Act 1990, making regullated stem cell research legal and the UK to again become a world leader in this field.

23 Oct 2006

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/5/1/5/1]

Advancing health: an enduring legacy

Sir Liam retired from the post of Chief Medical Officer after 13 years in May 2010. He left England a world leader in patient safety, infectious disease control, and stem cell research and empowered the public to be more aware of the health risks they could help prevent. Like many of his predecessors, he acted without fear or political fervour and is recognised as one of the great Chief Medical Officers.

11 May 2010

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/5/3/12]

Beyond Borders

© The Global Polio Eradication Initiative

Sir Liam’s Public Health campaigns were not just a national call to action but a global one. The World Health Organization recognised the innovative work done in the UK on patient safety during Sir Liam’s time as Chief Medical Officer. He proposed a World Alliance for Patient Safety in 2003 to adopt global standards and support member states in this field. This was establishment a year later and, as a champion of patient safety, Sir Liam was chair from the inception.

Among the far reaching programmes developed here were collaborative networks for reporting and learning from mistakes in health care and the Global Patient Safety Challenge which generated commitment from governments covering 78% of the world’s population to reduce harm to patients.

Continuing this work, in July 2011 Sir Liam was named the World Health Organization’s Envoy for Patient Safety. His current role is to mobilise political support to address patient safety at international levels and propose strategic actions for collaboration.

The Public Responds: Awards and Recognition

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/5/1/4/9, LD/5/1/5/2)

Sir Liam set up the Public Health Awards in 2009 to acknowledge those who had made a strong impact in the field. Among many other honours, recognition of his own significant impact came when Sir Liam received a Knighthood in 2002 with his wife Brenda and parents “Paddy” and June in attendance.

It was of great privilege that Sir Liam accepted the invitation to become Chancellor of Newcastle University in 2009; recognition of his local roots and international achievements. He commented:

“Nothing could give me greater pride than taking up the post of Chancellor in such a great city and in a university fit for the challenges of the 21st Century.“

Sir Liam Donaldson, 2009

07 Dec 2009

[Donaldson (Sir Liam) Archive, LD/5/1/7/1]

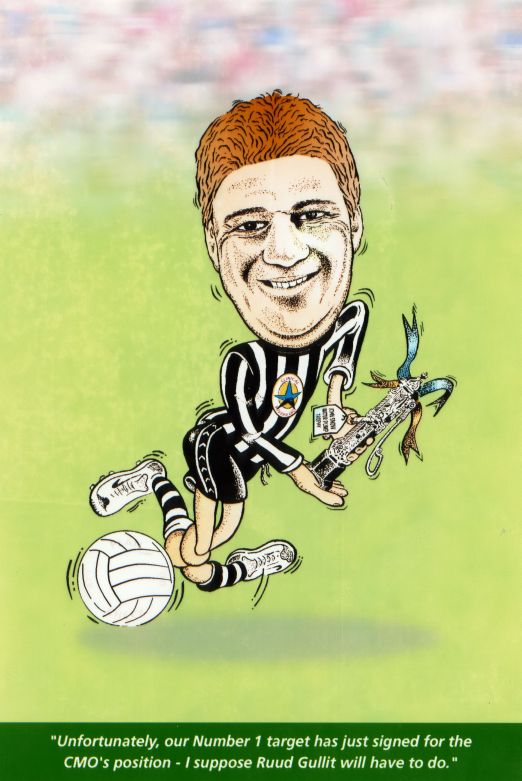

In his first act as Chancellor, Sir Liam showed recognition to some of his personal heroes with honorary degrees, including surgeon Lord Ara Darzi, who he worked closely with on National Health Service reforms, and Newcastle United footballing icon Alan Shearer.

![[Mary, Queen of Scots] In the Royal Palace of St. James's an Antient Painting. 1580. Delineated and sculpted by G. Vertue (1735)](https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/speccoll/files/2020/03/mary.jpg)