To celebrate Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee, we bring you a special Treasure of the Month.

2012 sees the 60th year of the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. It is astounding to think that no-one under the age of 60 has ever known any other monarch. It is unlikely that future generations will see a monarch of Britain on the throne for so long; however the Queen is not the first long-reigning monarch. Many of our former Kings and Queens have ruled for many decades, having ascended to the throne at a young age.

Elizabeth I was twenty-five when she became queen in 1558 and ruled for almost 45 years until her death in 1603. Edward III ruled for just over 50 years from the age of thirteen in 1327 to his death in 1377. Henry III ruled England for just over 56 years from 1216 to 1272. James VI of Scotland (who later became James I of England after the union of the English and Scottish crowns upon Queen Elizabeth I’s death in 1603) ruled Scotland for nearly 58 years from 1567 to 1625. However, both Henry and James came to the throne as infants, which rather increased their chances of having a long reign!

George III set a new record for the longest-serving monarch when he died in 1820, having ruled for almost 60 years. However, his son the Prince of Wales (later George IV) ruled as Regent from 1811 after George III’s descent into ‘madness’ reportedly brought on by the death of his youngest daughter and then as King from 1820 to 1830. Finally, the only monarch to have reigned longer than our current queen is Queen Victoria. Aged just 18 upon her ascension to the throne in 1837, she celebrated a Golden and Diamond jubilee before her death aged 81 in 1901, after 63 years and 216 days as queen.

Jubilees have, unsurprisingly, always been celebrated with much pomp and ceremony. Celebrations have taken place all over the country, memorabilia has been mass-produced and purchased by millions, and street parties have been held. George III’s golden jubilee was celebrated in 1809, as he entered his 50th year as King. Below is an extract from an account of the celebrations that took place in Newcastle. It states:

“The day was ushered in with ringing of bells; the flag was hoisted on the castle, on some of the churches, and by the ships in the river”.

The rest of the day was made-up of several acts of charity including meals of beef and plum pudding for the poor, the liberation of prisoners and a collection for the foundation of a public school. There were also church services throughout the day.

Not exactly the barbeque and pop concert from Buckingham Palace that we’ll be enjoying this year, but jubilant all the same!

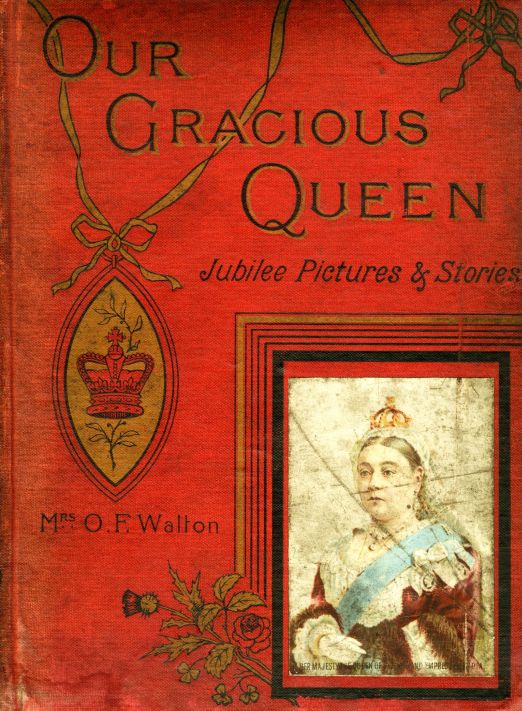

Queen Victoria’s Golden and Diamond jubilees involved public processions, banquets and thanksgiving services. Below is a memento from her Golden jubilee entitled Our Gracious Queen by Mrs O. F. Walton. It is a collection of images and stories of Queen Victoria’s life from 1887. There were great outpourings of affection for Victoria, who was hugely popular again in the late nineteenth century. Mrs Walton reminds us all to:

‘…thank God that He has spared her to us so long, and let us pray that He may spare her for many years to come…God grant, then, that each of us may be a true loyal subject of our dear Queen, always eager to stand up for her, always willing to obey her…’

Times and traditions may have changed over the years, but in 2012 with the monarchy undergoing a new surge in popularity, this jubilee is sure to bring as much celebration as those of George and Victoria did.

Oh and just in case you are wondering, Queen Elizabeth II will have to rule until 10th September 2015 to beat Queen Victoria’s record and become our longest-reigning monarch!

![[Mary, Queen of Scots] In the Royal Palace of St. James's an Antient Painting. 1580. Delineated and sculpted by G. Vertue (1735)](https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/speccoll/files/2020/03/mary.jpg)